Chapter 1: Artistic Ways of Knowing as a Catalyst to Creative Learning and Transformative Learning

Transformative Visual Literacy: An Important Dimension of Multimodal Learning

Transformations, openings, possibilities: teachers and teacher educators must keep these themes audible…To tap into imagination is to become able to break with what is supposedly fixed and finished, objectively and independently real. It is to see beyond what the imaginer has called normal or “common-sensible” and to carve out of order new experience (Maxine Greene, 1995, 17, 19).

In his book Art as Experience, John Dewey (1834/2005) writes about the connection between emotion and expression in art and learning processes. This type of creative learning involves close observation, curiosity, creativity, inquiry, and imagination. Dewey refers to the creative works of writers and artists such as Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Renoir, Raphael Santi, William Shakespeare, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Edgar Allen Poe, and John Keats to exemplify creative processes in art and writing. Artists are involved in a cycle of ordering and re-ordering images, patterns, perceptions, observations, memories, and emotions; the inner world is manifested in a poem, painting, or narrative. Creating art is a process of transformation that engages the imagination; higher levels of consciousness can be activated through the artistic process. Art can tap into the emotional and spiritual facets of learning.

Tangled scenes of life are made more intelligible in aesthetic experience; not, however, as reflection and science render things more intelligible by reduction to conceptual form, but by presenting their meaning as the matter of a clarified, coherent, and intensified, or ‘impassioned’ experience (Dewey, 1834/2005, p.302).

Individual and collective experiences, spontaneity and a freshness of ideas, universal truths, and the realm of the possible and ideal are all included in art from across cultures and across millennia. Achieving proportion, uniqueness, symmetry, and harmony may also be part of the product of an artistic creation. Art has a unique way of “telling a truth”:

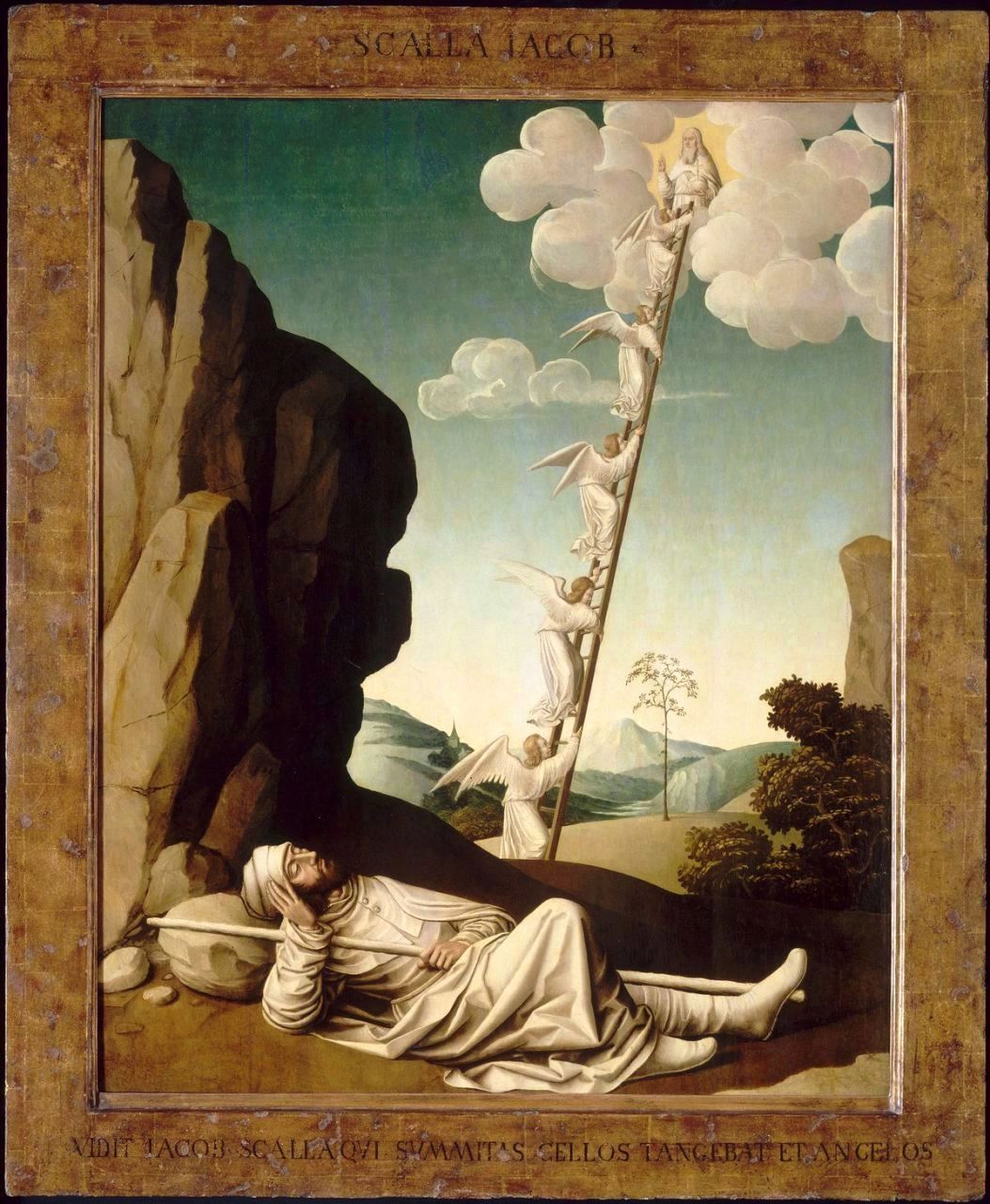

The object of art is to educate us away from art to perception of purely rational essences. There is a ladder of successive ways leading from sense upwards. The lowest state consists in the beauty of sensible objects; a stage that is morally dangerous because we are tempted to remain there….Works of art are means by which we enter through imagination and the emotions they evoke into other forms of relationship and participation than our own. (Dewey, 1934/2005, p. 347).

In other passages, Dewey writes about the liberating and united power of art:

Shelley said, ‘The great secret of morals is love, or a going out of our nature and the identification of ourselves with the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own. A [person] to be greatly good must imagine intensely and comprehensively.’ What is true of the individual is true of the whole system of morals in thought and action. While perception of the union of the possible with the actual in a work of art is itself a great good, the good does not terminate with the immediate and particular occasion in which it is bad. The union that is presented in perception persists in the remaking of impulsion and thought. The first intimations of wide and large redirections of desire and purpose are of necessity imaginative. Art is a mode of prediction not found in charts and statistics, and it insinuates possibilities of human relations not to be found in rule and precept, admonition, and administration (Dewey, 1934/2005, p. 363).

Artistic Ways of Knowing (AWOK) can elevate and enrich life experience; as educators, we are in a position to encourage art appreciation and awareness. The creative potential of visual art integrated with literary and non-fiction texts can lead to new understanding. To become immersed in art and artistic creations challenges individuals to be both spontaneous and disciplined. The landscapes of Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, or Albert Bierstadt and the poetry of John Keats, Bliss Carman, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, and Christina Rossetti reflect a range of emotions that can be catalysts for contemplation and creative self-expression. Vincent van Gogh’s paintings are notable for their intense portrayal of emotions such as joy, fear, anguish, surprise, and wonder. In one of his many letters to his brother Theo, Vincent wrote that “emotions are sometimes so strong that one works without knowing that one works, and the strokes come with a sequence and coherence like that of words in a speech or letter” (Dewey, 1934/2005, p. 75). Intellect and reason are insufficient to explain the deep mysteries of life and the presence of good amid destruction and evil. John Dewey (1934) refers to John Keats’s famous lines in “Ode to a Grecian Urn” that “beauty is truth, truth beauty-that is all/Ye know on earth and all ye need to know” to emphasize the importance of imaginative intuition as a form of truth that can unravel life’s uncertainties and mysteries. The emotions present in Vincent van Gogh’s self-portraits or landscapes such as almond trees blossoming or a night café amid a starry sky. Dewey emphasizes qualities such as awareness, empathy, close observation, and reflection that are common to many artists: “Such fullness of emotion and spontaneity of utterance come, however, only to those who have steeped themselves in experiences of objective situations to those who have long been absorbed by observation of relevant materials and whose imaginations have long been occupied with reconstructing what they see and hear (Dewey, 1934/2005, p. 75). Dewey’s ideas (1934/2005) remind educators that the future of arts integration provides opportunities for development and growth of emotional, social, aesthetic, and intellectual skills. Listening, speaking, writing, reading, viewing, and representing are enriched with multi-modal literacy development.

Conceptions of Visual Literacy

A major focus highlights the way visual or artistic images can be used in an integrated and complementary way to enrich literary genres and forms used in English language arts and related disciplines. The art images and poetry featured in this text are derived from the Public Domain (PD); links to contemporary texts are also provided. From an interdisciplinary perspective, visual images can complement ideas, concepts, and themes in literature, expressive arts, psychology, sociology, world issues, history, ethnography, environmental sciences, cultural studies, graphic design, mathematics, engineering, and other fields. Creative writing, drama, storytelling, and the analysis of literary works that include poetry, novels, and non-fiction can be enhanced when visual images are used. Skills in listening, speaking, writing, reading, viewing, and representing can be developed and extended when multimodal literacies are encouraged. Literacy learning is extended with the emergence of the Internet, multimedia, digital media, and now Artificial Intelligence (AI), literacy skills The New London Group (1996) emphasizes that a pedagogy of multiliteracies “focuses on modes of representation much broader than language alone. These differ according to culture and context-in an Aboriginal community or in a multimedia environment, for instance—the visual mode of may be more powerful and closely related to language than more ‘literary’ works would” (p.64).

The New London Group conceptualizes literacy as dynamic, interactive, evolving, multimodal, and transformative.“New communications media are reshaping the way we use language” and that “literacy educators and students must see themselves as active participants in social change, as learners and students who can be active designers and makers (Jewitt, 2008; Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996; Kress, 2003; Serafini, 2017). The curriculum is also seen as dynamic and emergent; learners are actively involved in negotiating, critiquing, and creating new curricula. Authentic “real world” learning opportunities, cross-cultural and cross-curricular discourses, critical thinking, collaboration, and transforming curricula in new ways encourage meta-cognitive and meta-linguistic abilities to develop (New London Group, 1996).

Visual literacy is one component of multimodal literacies of visual literacy are also varied. For example, John Debes (1969) writes that “visual literacy refers to a group of vision-competencies a human being can developing by seeing and at the same time having and integrating other sensory experiences” (p.27). Skills and abilities such as close observation, perception, pattern recognition, and decoding can enhance individuals’ ability to appreciate and comprehend the world more fully. Communication skills are extended and individuals are able to express themselves more creatively. R. Williams (2003) explains that “the integration of intuitive, visual knowing with rational cognitive processes generates expressions of whole-mind cognition that have the potential to foster greater creativity, more powerful problem-solving abilities, and balance between quantitative and qualitative analyses” (p.2). He explains that individuals’ perceptions of visual images can influence their emotional, cognitive, and behavioural learning processes. Conceptions of “visual intelligence” have been influenced by “a cluster of fields in communication, including photojournalism, rhetoric, mass communication, advertising, digital media and interpersonal and intrapersonal communication”(Williams, 2003, Key Note Address, Rochester Institute of Technology, RIT, p.2). Rick Williams (2003) connects visual intelligence as intersecting and informing Howard Gardner’s (1981) theory of multiple intelligence. Williams writes:

All eight intelligences have significant visual components: visual/spatial intelligence is clearly visual; musical intelligence employs vision both to read and write music and music often generates mind’s eye imagery or dream-like meditations; intra-personal intelligence employs dream imagery, and both intra- and interpersonal intelligences employ sight as does bodily kinesthetic intelligence; linguistic and mathematical intelligences (the rational intelligences) use both physical sight and generate mind’s-eye imagery as in thinking about a geometric figure or imagining a scene from literature; and naturalistic intelligence is an integrating process that employs the other intelligences, often in visual ways, to understand the natural world (p.7).

There is an important narrative component to visual texts; for example, the 20,000 year old paintings in the Lascaux petrographs of bison, bulls, deer, bears, mammoths, and other animals tell a story about humans’ survival, their relationship with themselves, the animals around them, and the natural world during the Palaeolithic time period. Visual literacy skills and strategies can help individuals analyze and interpret these stories (Beier, 2013). The definition of visual literacy provided by Deborah Curtiss’s (1987) definition of visual literacy most closely aligns with the way visual literacies are conceptualized in this text:

Visual literacy is the ability to understand the communication of a visual statement in any medium and the ability to express oneself with a least one visual discipline. It entails the ability to understand the subject matter and meaning within the context of the culture that produced the work, analyze the syntax—compositional and stylistic principles of the work, including the disciplinary and aesthetic merits of the work and grasp intuitively the Gestalt, and the interactive and synergistic quality of work. (p. 34).

The chapters in this text provide many examples of visual images that can be used to complement and enrich teaching and learning in English language arts and related disciplines. It is also important to note that while a wider focus of this book is on visual art connections and poetry, other creative approaches to teaching English language arts that include storytelling, transcultural texts, letters, drama, and short stories will be explored in various sections.

Multimodal Learning

I take the position that multi-modal literacies enrich and deeper our understanding of texts in ways that, potentially, can empower and inspire. The second book Transformative Approaches to Teaching English Language Arts Through Poetry, Art, and Related Texts is meant to provide complementary art-text resource guides that are theme-based and that further exemplify the possibilities of integrating art in literacy courses at the secondary level. Book Two includes themes such as Myths and Legends, A close look at the sea, and Fantastical Creatures and Mythic Monsters. The theoretical and practical foundations of Book One (Artistic Literacies) inform the themes in Book Two. The themes align with specific curricula from the Grades 10-12 ELA curriculum in Manitoba and other Canadian provinces. These books are an invitation for educators to further design innovative ways that arts based pedagogies can be a catalyst for creative learning in diverse educational contexts and in the larger classroom of life.

To read an essay by Elliot Eisner on the art of education, please open the link here.

To read more about aesthetic education please visit the Maxine Greene Institute website here.

To read more about multiliteracies please open the link here.

English Language Arts Curriculum Links

Effective English language arts planning provides opportunities to explore significant and complex ideas (e.g., extinction versus the topic of dinosaurs) and to consider questions for deeper understanding. Such questions can be used to initiate and guide rich learning experiences and give students direction for developing context about a topic or issue. It is essential to develop questions that are evoked by students’ interests and have potential for rich learning. The process of constructing questions can help students to grasp the important disciplinary or transdisciplinary ideas that are situated at the core of a particular curricular focus or context. These broad questions will lead to more specific questions that can provide a framework, purpose, and direction for the learning experiences in a lesson, or series of lessons, and help students to connect what they are learning to their experiences and life beyond school. In the context of play and inquiry, questions and wonderings could emerge during learners’ engagements. The 2020 Province of Manitoba English language arts curriculum framework emphasizes the importance of close observation, inquiry, and multimodal literacy learning:

Teachers would observe learners in action to notice these questions in order to help inform further and deeper learning. Prompts in many forms (e.g., objects, concepts, specimens, visuals, events, books) can also inspire wondering and questioning to guide deeper learning. Through rich learning experiences and processes to deepen understanding, students are given opportunities to engage meaningfully in the four practices of English language arts. By exploring broad questions and significant ideas, students will be using language as sense making, system, exploration and design, and power and agency. When planning, teachers need to ensure that the learning experiences are rich enough to engage students meaningfully in all four practices ( p. 59).

While the curriculum guides can provide a basic foundation for implementation, this book will provide specific examples of artistic and literary texts in addition to questions that can promote creative and critical thinking. (Manitoba Curriculum, 2020). General Learning Outcomes (GLOs) and many specific learning outcomes can also be strengthened when Artistic Ways of Knowing (AWOK) are integrated in meaningful ways. Learners can explore their ideas, thoughts, and feelings critically in response to visual and literary texts. Learners have opportunities to express their ideas in poem, drama, exposition, and other writing and visual forms. Learners would also have opportunities to collaborate with their peers in sharing new knowledge. With artistic literacies students have unique opportunities to explore their ideas, thoughts, and feelings; they can respond personally and critically to a range of texts from varied cultural and historical time periods. Through letters, journals, essays, presentations, and creative works, students’ writing, speaking, reading, and listening skills can be developed.

The poems, related texts, and work of visual art featured throughout these books and resource guides can help educators encourage literacy as critical exploration, sense making, and a catalyst to personal agency and transformative change. Exploring works of art and then creating works of art can develop students’ skills of close observation and interpretation. Skills in viewing and representing their ideas can begin to flourish in a learning environment that is similar to an artist’s atelier. Eisner notes that learners who begin to “think like an artist” can develop keen skills of observation, reflection contemplation, and practical application. Metacognitive skills are meaningfully integrated in the process of linking texts to works of art. For more details, please open the link here. The following art images and poems highlight the way art images can be complemented with poetry; close observation, reflective thinking, and creative possibilities for teaching English language arts can be further explored.

“In Summer”by Paul Laurence Dunbar

Oh, summer has clothed the earth

In a cloak from the loom of the sun!

And a mantle, too, of the skies’ soft blue,

And a belt where the rivers run.

And now for the kiss of the wind,

And the touch of the air’s soft hands,

With the rest from strife and the heat of life,

With the freedom of lakes and lands…..

To read more of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry, please open the link here.

Learning Objectives

A personal interpretation of art

1. The teacher can show students various art images, without any details of provenance, materials used, construction details, by whom, date, and so on.

2. Students can brainstorm their ideas on the work of art. Their ideas could be visually mapped (see Sayre, 2009, pp. 101-102). The teacher could then release a few verbal details (e.g. sculpture, made in Africa, on what date).

3. Have any of the brainstorming ideas been confirmed? Which ideas have been confirmed? Which are not applicable?

4. Students can write their preliminary impressions of the image after being given only partial information.

5. Finally, reveal the whole context of the work of art; students can integrate their personal impressions with the work of art along with the information about the social, cultural, and historical context of the art work as well as specific features about the work of art (e.g. subject matter, importance of the medium (sculpture, water colour, etc.) line, colour, shape, texture, etc.).

To learn more about Key Elements of Art please open the Getty Art Museum page here.

To read Writing about art (sixth edition) by Henry Sayre (2009) , please open the link here.

Encouraging Empathy and Awareness with Art and Poetry

“Trees”by Bliss Carman

IN the Garden of Eden, planted by God,

There were goodly trees in the springing sod,-

Trees of beauty and height and grace,

To stand in splendor before His face.

Apple and hickory, ash and pear,

Oak and beech and the tulip rare,

The trembling aspen, the noble pine,

The sweeping elm by the river line;

Trees for the birds to build and sing,

And the lilac tree for a joy in spring;

Trees to turn at the frosty call

And carpet the ground for their Lord’s footfall;

Trees for fruitage and fire and shade,

Trees for the cunning builder’s trade;

Wood for the bow, the spear, and the flail,

The keel and the mast of the daring sail;

He made them of every grain and girth

For the use of man in the Garden of Earth.

Then lest the soul should not lift her eyes

From the gift to the Giver of Paradise,

On the crown of a hill, for all to see,

God planted a scarlet maple tree.

To read Bliss Carmen’s edited volume (illustrated) of “The World’s Best Poetry” (J.D. Morris & Co, Philadelphia, 1904) please open the Internet Archive link here.

The sun descending in the west,

The evening star does shine;

The birds are silent in their nest,

And I must seek for mine.

The moon, like a flower

In heaven’s high bower,

With silent delight,

Sits and smiles on the night.

William Blake (1757-1827), Songs of innocence and experience: Two contrary states of the human soul. Edited by George Cowling. London: Methuen & Co., 1925. Internet Archive.

Resource: J.Patrick Lewis (Ed.). Book of Nature Poetry (p. 24). National Geographic Society.

“Stars”by A. E. Housman

Stars, I have seen them fall,

But when they drop and die

No star is lost at all

From the star-sown sky.

The toil of all that be

Helps not the primal fault;

It rains into the sea,

And still the sea is salt.

Students can also explore connections between art images, poems, and other literary forms such as letters and biographical texts.

Excerpt from Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 Letter to His Friend Bernard:

Vincent van Gogh felt like an outcast, unappreciated, and misunderstood, for the most part, from society. His solace came from painting and from the few friendships she had with fellow painters and his brother Theo. van Gogh’s existential reflections reveal his hope in the mysteries of the universe that might offer spiritual transcendence and an alternative existence without anguish and suffering.

Yet our real and true lives are rather humble, these lives of us painters, who drag out our existence under the stupefying yoke of he difficulties of a profession which can hardly be practiced on this thankless planet on whose surface ‘the love of art makes us lose the true love.’

But seeing that nothing opposes it—supposing that there are also lines and forms as well as colors on the other innumerable planets and suns—it would remain praiseworthy of us to maintain a certain serenity with regard to the possibilities of painting under superior and changed conditions of existence, an existence changed by a phenomenon no queerer and no more surprising that the transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, or of the white grub into a cockchafer.

The existence of a painter-butterfly—seems to me an instrument that will lag far, far behind. For look here: the earth has been thought to be flat. It was true, so it is still today, for instance between Paris and Asnieres. Which, however, does not prevent science from proving that the earth is principally round. Which no one contradicts nowadays.

But nothwithstanding this they persist nowadays in believing that life is flat and runs from birth to death. However, life too is probably round, and very superior in expanse and capacity to the hemisphere we know at present ( Vincent van Gogh, 1888, in Auden, W.H. (Ed) (1963), Van Gogh: A self portrait-letters revealing his life as a painter, New York Graphic Society, p. 303).

For more information about Vincent van Gogh’s art and letters please see Chapter 7 of this text.

Vincent van Gogh: Excerpts from a Letter to His Brother Theo (September, 1888)

“You are kind to painters, and I tell you, the more I think it over, the more I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people.” (van Gogh, Arles, 1888 in Auden, W.H. (Ed.), 1963, p. 329.)

“My eyes are still tired, but then I had a new idea in my head and here is the sketch of it…it’s just simply my bedroom, only here color is to do everything, and giving by its simplication a grander style to things, to be suggestive here of rest or of sleep in general. In a word, to look at the piture ought to rest the brain or rather the imaginatinon. “ (van Gogh, September, 1888, in Barent, Burto, & Cain, 2006, p. 895).

Excerpt from Vincent van Gogh’s Letter to his artist friend Bernard (July, 1888)

“I have just finished a portrait of a girl of twleve, brown eyes, lack hair and eyebrows, gray-yellow flesh, the background heavily tinged with malachite green, the bodice blood red with violet stripes, the skirt blue with large orange polka dots, an oleander flower in her charming little hand. It has exhausted me so much that I am hardly in a mood for writing. Till soon again, and once more many thanks, Vincent.” (Vincent van Gogh, 1888, in Auden, W.H. (Ed). Letters, 1963, p. 307).

The largest verbal frame surrounding a work of art-larger even than the body of critical and art historical discussions about it–has to do with its place in the larger scheme of things, art historical and otherwise. Each work is conceived in a particular time and in a particular place, and to some degree it is bound to reflect the circumstances of its conception. (Sayre, 2009, p. 81).

Examining the cultural and historical context of art offers some of the most exciting possibilities for writing about art. Bring your other coursework in the university to bear on what you study in art. Think about the ways in which your history course, or your sociology course, might inform the artworks you see. Such perspectives can only challenge your own assumptions about the work of art, and every time you challenge art assumptions, greater understanding is the only result (Sayre, 2009, p. 85).

- Explore the social, cultural, and historical context of any work of art and describe your findings in a paragraph or short essay. What historical events and movements (in politics, technology, culture, educational studies in the arts, social sciences, and sciences, etc.) were happening at the time this particular work of art was created?

- Analyze the ways works of art reflect broader social patterns of belief and behavior. How might “other truths” be revealed in a particular work of art? For example, Sayre notes that “Feminist art criticism has been particularly effective of drawing attention to the ways in which Western art has codified and institutionalized the male gaze as the preeminent point of view…One of the strategies of the ‘masculinist’ gaze is to transorm the very idea of vision into a question of form”(Sayre, p. 83).

Questions for Further Inquiry

- What is your own first response to the paintings? In interpreting the painting, consider the subject matter, the composition (for instance, balanced masses, as opposed to an apparent lack of equilibrium), the technique (for instance, vigorous brushstrokes of thick paint, as opposed to thinly applied strokes that leave o trace of the artist’s had), the colour, and the title.

- Now that you have read the poem, do you see the painting in a somewhat different way?

- To what extent does the poem illustrate the painting, and to what extent does it depart from the painting and make a very different statement?

- Beyond the subject matter, what (if anything) do the two works have in common? “ (Barnet, Burto, and Cain, 2006, pp. 891-892).

- In viewing a work of visual art and in reading varied poems, do other texts come to your mind? If so, which ones? Which texts are you reminded of? Can you relate a life experience to either the painting or the poem?

“A Summer Wish” by Christina Rossetti

Live all thy sweet life through

Sweet Rose, dew-spent,

Drop down thine evening dew

To gather it anew

When day is bright:

I fancy thou wast meant

Chiefly to give delight.

Sing in the silent sky,

Glad soaring bird;

Sing out thy notes on high

To sunbeam straying by

Or passing cloud;

Heedless if thou art heard

Sing thy full song aloud.

Creative and Transformative Learning: Building Learning Architectures of Possibility

Art offers life; it offers hope, it offers the prospect of discovery; it offers light. Resisting, we may make the teaching of the aesthetic experience our pedagogic creed (Green, 1995, p. 133).

Effective practices in English language arts (ELA) continue to evolve by ongoing dialogue between theory and reflective practice. ELA can help students develop foundational knowledge in listening, speaking, writing, reading, viewing, and representing. Through multi-modal texts (drama, visual art, poetry, literature, non-fiction, new literacies) students have opportunities to witness and closely observe the way language and artistic ways of knowing can open new possibilities for knowledge creation. Educators create greater inclusion in any given learning context (and at any level) when they tap into multiple modalities of learning. Language, for example, can be used to expression historical information, artefacts, literature, food, music, celebrations, and rituals. Reading and writing narrative stories have the potential to engage more than at the cognitive level; they can engage our heart, imagination, and spirit, connecting individuals from one layer of consciousness to another (Chapman Hoult, 2012).A visual mapping of a person’s life story might include symbolic representations of emotional growth, setbacks, accomplishments, and dreams. Paintings can be viewed as stories with multiple interpretations. There is a vibrancy to reading, visualizing, and performing stories. Music can also express emotion and thought; music has the capacity to transport individuals into different modes of consciousness. The universal language of music might tap into experiences and intuitive modes of learning that occur outside superficial levels of awareness. Artistic Ways of Knowing (Awok) can also be powerful catalysts to expanding and extending knowledge and creativity. Multi-modal ways of knowing challenge learners to be attentive to nuances and shapes, patterns, colours, sounds, rhythms, figures of speech, contours, lines, and other details For Randee Lipson Lawrence (2005), art is a way of knowing. She writes:

Artistic forms of expression extend the boundaries of how we come to know by honoring multiple intelligences and Indigenous knowledge. Artistic expression broadens cultural perspectives by allowing and honoring diverse ways of knowing and learning. Making spaces for creative expression in the adult education classroom and other learning communities helps learners uncover hidden knowledge that cannot easily be expressed in words. It opens up opportunities for learners to explore phenomena holistically, naturally, and creatively (p. 107).

Earlier, Maxine Greene (1995) wrote about the potential of multi-modal ways of knowing. She sees art and literature as powerful catalyst to personal agency and social change. In Releasing the Imagination Greene (1995) explains that educational contexts that provoke critical consciousness, thoughtfulness, and empathy are ones where teachers and learning are “conducting a kind of collaborative search, each from [their] lived situation” (p.23).Teachers need to be keen observers in understanding the “imaginative consciousness of their students” (p.25). Communication and interconnectedness between different artistic art forms is applied in meaningful ways throughout curricula can advance creative learning. Learning also involves reaching out and tapping into perceptual, cognitive, intuitive, emotional, and imaginative ways of knowing. As Greene observes, the arts, in particular, have a unique ability to “release imagination” (p.27). Greene emphasizes that the rigid dichotomy between “cognitive rigour,” the analytical, and the rationale vs. the imaginative, spiritual, and affective needs to be challenged in favour of a holistic integration of learning modalities and capacities. Too often, feelings, emotions, and intuition are marginalized or trivialized despite the reality that emotions and emotional states such as fear and anxiety influence learning processes. The arts should not be on the periphery of the educational curricula but rather they should be in the forefront; moreover, narratives and arts from individuals historically marginalized and not well known should be explored in an effort to extend transcultural knowledge and empathy. Lesser known stories need to be brought into the forefront to challenge tropes, stereotypes, and inaccurate assumptions regarding culture, class, race, ethnicity, and religion. It is important to highlight narratives of courage and survival. A novel like Toni Morrison’s (1970) The Bluest Eye, for example, can be explored through a more complex lens that analyzes historic racism and sexual abuse. Stories like Toni Morrison’s Beloved or Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man can be explored through of white supremacist practices that as Cornell West writes meant living in “the ragged edges —of not being able to eat, not to have shelter, not to have health care—all this is infused into the strategies and styles of black cultural practices” (West, 1989, p. 93). The experiences of Claudia and Pecola are nuanced and complex and that it is vital to contextual their experiences from an understanding of cultural and political oppression (West in Green, 1995, p. 165). Green further writes:

To help the diverse students we know articulate their stories is not only to help them pursue the meanings of their lives—to find out how things are happening and to keep posing question about the why. It is to move them to learn the new things Freire spoke of, to reach out for the proficiencies and capacities, the craft required to be fully participant in this society, and to do so without losing consciousness of who they are. (p. 165).

Greene asserts that “encounters with the arts have a unique power to release imagination. Stories, poems, dance performances, concerts, paintings, films, plays—all have the potential to provide remarkable pleasure for those willing to move out toward them and engage with them” (p. 28). Texts should reflect the “multiplicity” of lived experiences and if students lack “access to the language of power” it will be difficult for them to surmount situational and institutional barriers. Teachers have a responsibility to be ongoing learners, to realize “how deeply literacy is involved in relations of power and how it must be understood in context and in relation to a social world” (p. 110). Working to create learning climates that empower all learners begins by valuing and cherishing the unique lived worlds of students who have historically been isolated and marginalized. “Many of the alienated or marginalized are made to feel distrustful of their own voices, their own ways of making sense, yet they are not provided alternatives that allow them to tell their stories or shape their narratives or ground new learning in what they know” (pp. 110-111). Classroom communities, notes Greene, need to be life-affirming and open to difference and plurality. In helping diverse learners develop and narrative their life stories, educators are also helping them “pursue the meaning of their lives” (Greene, p.111).

Multi-modal literacy learning and encouraging artistic ways of knowing and expression enable learners to “transcend the given” and enter a “field of possibilities” (p.111) and hope. Expanding “art education” to include music education, teaching painting, sketching, graphic design, creative writing, and dance education are ways of expanding awareness and sensitivity to multiple modes of learning. Imagination enables learners to “particularize, to see and hear things in their concreteness” (p.29). Green expands on the important role that imagination can play in “awakening” individuals to think more deeply and reflectively:

But the role of imagination is not to resolve, not to point the way, not to improve. It is to awaken, to disclose the ordinarily unseen, unheard, and unexpected….Even mainstream art forms may then be viewed as something other than carriers of messages from men in power and norms of the majority once we go below their surfaces and act for ourselves on those intimations of freedom and presence that we find. Art from other cultures –South Indian dance, Mayan creation myths, Chippewa weaving, Balinese puppets—may be given honoured places on the margin, as individuals are gradually enabled to bring this art alive in their own experience, as they are gradually freed to let imagination do its work. In time, as many of us know, these works of art may radiate through our variously lived worlds, exposing the darks and the lights, the wounds and the scars and the healed places, the empty containers and the overflowing ones, the faces ordinarily lost in the crowds (pp. 28-29).

Drawing on myriad authors, educational theorists, and artists such as Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Georgia O’Keefe, F.Scott Fitzgerald, Saul Bellow, Edward Hopper, Hannah Arendt, Richard Rorty, Paulo Freire, and John Dewey, Greene (1995) advocates for the value of integrating arts based ways of knowing as a catalyst to initiative, agency, and transformation. Greene notes that imagination is also not enough, in itself. Social awareness and social consciousness is needed to envision a world that is more peaceful and sustainable. Working toward a higher consciousness and working toward creating a more enlightened and equitable world should also be central goals in education. Building community and “reaching toward others in a public space” through the arts can be a catalyst for learners envisioning unexpected possibilities.

Transformative Learning and Links to Creativity

We want our classrooms to be just and caring, full of various conceptions of the good. We want them to be articulate, with the dialogue involving as many persons as possible, opening to one another; opening to the world. And we want our children to be concerned for one another, as we learn to be concerned for them. We want them to achieve friendship among one another, as each one moves to a heightened sense of craft and wide-awakeness, to a renewed consciousness of worth and possibility (Green, 1995, p. 168).

Greene’s (1995) transformative views to re-vision education in more equitable and vital ways are consistent with theoretical perspectives of transformative learning theory and creative learning (Cranton, 1994; Mezirow, 1981; Magro, 2001; Magro and Polyzoi, 2009, Mezirow and Associates, 2006; O’Sullivan, Morrell, and O’Connor, 2001; Taylor and Associates, 2012). Transformative learning is about “change, dramatic, fundamental change in the way we see ourselves and the world in which we live’ (Merriam, Caffarella, and Baumgartner, 2007, p. 130). Earlier, Jack Mezirow (1981) explained that meaning perspectives and frames of reference are often rooted in taken-for-granted beliefs and assumptions within a given social and cultural context. It is when we experience a “disorienting dilemma” such as the death of a close family member or a significant marker event such as an illness, the loss of a job or a move that our assumptions and beliefs are challenged. As individuals mature and evolve, they have opportunities to reflect more critically on faulty or incomplete assumptions about themselves, others, and the world. Mezirow (1981) identified ten stages of transformative learning and perspective transformation when working with over 80 women who returned to college as mature adult learners. He identified these stages (which may be linear or recursive; sudden or dramatic) These include:

- Experiencing a disorienting dilemma (e.g. the loss of a loved one, a serious accident, a move, job transition or loss, emotional crisis, etc.).

- Undergoing self-examination

- Conducting a critical assessment of internalized role assumptions and feeling a sense of alienation from traditional social expectations

- Relating one’s discontent to similar experiences of others or to public issues—recognizing that one’s problem is shared and not exclusively a private matter

- Exploring options for new ways of acting

- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles

- Planning a course of action

- Acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans

- Making provisional efforts to try new roles and to assess feedback

- Reintegrating into society on the basis of conditions dictated by the new perspective (Mezirow, 1981, in Cranton, 1994, p. 23)

Patricia Cranton (1994) further developed Mezirow’s ideas and provided practical strategies for educators to work toward transformative or deeper level learning. For Cranton, transformative learning is a life-long process of growth and development. Cognitive, emotional, sociolinguistic, and spiritual ways of knowing are explored through learning opportunities that encourage reflective observation, the exploration of alternative perspectives, and having opportunities to challenge, refute, reflect, and hear others do the same”(p.27). Reflecting on meaning perspectives can apply to the way a person thinks, feels, and experiences life events. Social norms, cultural expectations, family upbringing, community connections, peer relationships, socialization, and language codes all influence an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Cranton writes that “the sources of psychological meaning perspectives are often buried in childhood experiences (including trauma) and may not be easily accessible to the conscious self” (p. 29). Cranton notes that individual differences in term of personality, learning style, motivational style, cognitive style, and culture are “readiness” factors that can influence individual journeys of learning. Educators need to be able to assess and gauge the unique strengths and skills of each learner. While the ideas in transformative learning theory have been applied primarily with adult learners, many of the strategies are relevant to older adolescents and young adults. Cranton highlights the importance of experiential learning, multi-modal learning opportunities which tap into students’ unique learning styles, critical incident questionnaires, letter and journal writing, and debate. Encouraging questions about the content, process, and premise of a particular text, for example, can lead learners to be more reflective (What is being said? How is the information being expressed? Why? Whose viewpoint is included? Whose viewpoint is left out?). Cranton (1994) emphasizes that the educator’s own personality and perspectives on teaching and learning play a significant role in creating a climate conducive to transformative learning:

Educators must be adult learners continually striving to update, develop, expand, and deepen their professional perspectives both on their subject area and on their goals and roles as educators. The educator who is not a learner becomes an assembly-line working implementing well-worn habitual tricks and techniques to process learners’ acquisition of knowledge and skills. The educator who is not a learner cannot act as a model of learning. The educator who is not a critically self-reflective learner will not be likely to stimulate critical reflection among learners…The learner-educator can use strategies such as writing critical incidents, keeping a journal, completing a repertory grid, writing a life history, conducting a criteria analysis, or engaging in a crisis-decision simulation. For most people, discussion with a colleague or friend will be an essential ingredient of any strategy for explicating assumptions. Even unconscious assumptions can be ferreted out by a keen observer ( Cranton, 1994, p.228).

Mezirow and Associates (2000) note that emotions are also central to meaning making and perspective transformation and that the arts all have their own unique languages that inform meaning.

Art, music, and dance are alternative languages. Intuition, imagination, and dreams are other ways of making meaning. Inspiration, empathy, and transcendence are central to self-knowledge and to drawing attention to the affective quality and poetry of the human experience. Dirkx writes of learning through soul involving a focus on the interface where the socio-emotional and the intellectual world meet where inner and outer converge (2000, p.6).

It is important to note that the “stages” are not always linear and that they may be recursive, gradual or sudden; the paradigm shift in thinking is relatively permanent and significant changes occur not just in thought and feeling but in actions and behaviors. There are different strands of transformative learning that highlight varied ways of knowing, but the definition provided by O’Sullivan and associates (2001) best illuminates the individual and collective dimensions of TL:

Transformative learning involves experiencing a deep, structural shift in the basic premises of thought, feeling, and actions. It is a shift in consciousness that dramatically and permanently alters our way of being in the world. Such a shift involves our understanding of ourselves and our self-locations; our relationships with other humans and with the natural world; our understanding of relations of power in interlocking structures of class, race, and gender; our body-awareness; our visions of alternative approaches to living; and our sense of possibilities for social justice and peace and personal joy. (O’Sullivan, 2001, p.11).

There are also many parallels between transformative learning and creative learning. Tsai (2013) notes that like transformative learning, creative learning involves an exploration of new perspectives and paradigms. Creative learning is “an experimental, destabilizing force; it questions starting points and opens up the outcome of the curriculum” (Sefton-Green, Thomson, Jona, and Bresler, 2011, p.2). Personality traits such as an openness to new experience, the ability to think divergently, curiosity, intrinsic motivation, and flexibility are often associated with creative individuals.

Creative learning is interactive, incorporating discussion, social context, sensitivity to others, and the acquisition and improvement of literacy skills; it is contextual and has a sense of purpose and this cannot be based in small unit of testable knowledge (p.41).

As educators, we have to consider whether existing educational cultures encourage or impede imaginative and creative learning. To what extent is enough time given for students to reflect, envision, dream, and think in imaginative ways? Newton and Newton (2016) assert that creativity does not exist in a vacuum and that educational systems need to support the professional development opportunities for teachers who wish to integrate creative teaching and learning strategies. They also explain that while creative thinking is connected to problem solving and practical wisdom, the moral and ethical context must also be considered. Artificial Intelligence, for example, has the creative potential to help in many ways but the deleterious impact of AI on the world of work and human interactions must also be considered. Mezirow and associates (2012) noted that individuals who possess emotional intelligence skills such as self-awareness and empathy are more likely to be open to perspective taking and transformative learning experiences:

Effective participation in discourse and in transformative learning requires emotional maturity—awareness, empathy, and control—what Goleman (1998) called ‘emotional intelligence’—knowing and managing one’s emotions, motivating oneself, recognizing emotions in others, and handling relationships as well as clear thinking. (p.79).

Heather Bruce (2011) notes that empathy should be extended to “nonhuman species, for the soil, water, and air in which all of life depend” (p. 13). She further asserts that:

English teachers specialize in questions of vision, values, ethical understanding…Our expertise in addressing the aesthetic, ethical, and sociopolitical implications of the most pressing human concerns of our time enable us to reach toward and embrace environmental problems (pp. 13-14).

Magro and Piece (2011) observe that ecoliteracies and inter-textual studies are ways to encourage students to explore issues that impact their lives. Interdisciplinary approaches, experiential, and place-based learning are ways to encourage empathy for all living things. The setting of a literary work or a painting can be explored through a geographical, psychological, social, cultural, or historical lens. Nancy Mack (2012) wrote that artistic forms of expression can become “emotional rehearsals for the larger social experiences of our lives, culture, and epoch” (p. 21). Studying art and literature can encourage an exploration of emotion, logic, memories, thoughts, and perceptions. Integrating art with literature and non-fiction can help learners make emotional connections to the characters and experiences. Edward Taylor (2012) and Magro (2009) asserts that there are many factors that can influence creative and transformative learning: the readiness of the learner, personality dispositions, the skill and philosophy of the educator, learning styles, the philosophy and mission of a particular school, the subject area, and opportunity and access to teaching and learning resources. Cognitive rigidity or a “fixed mindset” (Dweck, 2011), Psychological, situational, and institutional barriers can impact the trajectory of any learning experiences. Artistic Ways of Knowing can help to remove some of these barriers and pave the way for engaging learning. Teaching styles are also important to consider if creative learning to occur. A teacher’s repertoire of pedagogical knowledge, intra and interpersonal skills, beliefs about the potential of creativity, a non-hierarchical teaching style, diverse multi-modal assessment approaches, a keen understanding of individual learners strengths and challenges, and the motivation to integrated artistic literacies in the classroom all may contribute to the constellation of the teaching/learning climate in the classroom.

Art Can Challenge, Disrupt, and Inspire

Artistic works have the capacity to act as catalysts and “disorienting dilemma” that challenge familiar frames of reference and that encourage individual to explore new perspectives and paradigms. Lipson Lawrence (2005) notes that artistic images can be a way to come to a deeper understanding of human emotion and life’s challenges—grief, fear, and the mysteries of the unknown. Engaging with art imaginatively, perceptually, affectively, and cognitively requires energy and motivation (Green, 1995, p.225). From the perspective of analytical psychology, personal transformation is a “fundamental change in one’s personality involving conjointly the resolution of a personal dilemma and the expansion of consciousness resulting in greater personality integration” (Boyd, 1989, p. 489 in Cranton, 1994, p. 55). Symbols, dreams, visual images, and archetypes relating to personal life journeys might be explored through creative artistic expression involving painting, bricolage, and poetry writing. Exploring artistic ways of expression has the potential to impact spiritual and affective learning. Lipson Lawrence (2005) notes that our experiences are animated by unconscious and conscious processes and a work of art, poem, or related text can awaken dormant emotions and thoughts. Mythic journeys often feature a hero’s quest in search of something of value that will improve life and bring peace to individuals and communities. In a similar way, each individual is on a journey and quest to understand, heal, gain insight, and find meaning in life experiences. Symbols are “pre-linguistic abstractions that emerge from archetypal material and almost always have an inherent meaning as well as a representational meaning” (William Scott Wallace, 2008, p.38). Alchemists recorded their work of turning metal into gold only in writing but they also created fabulous paintings that emerged from their dreams and visions; often these pictures featured symbols that had multi-layered meaning about the nature of good and evil. Lipson Lawrence suggests that an exploration of art (both in studying art and in creating art) learners can enrich their spiritual awareness.

Exploring the Symbols and Dreamscapes in Art can be a Catalyst for Learners to Explore their own Emotions, Dreams, and Intuitions

“The Far Field”By Theodore Roethke

(Excerpt)

I dream of journeys repeatedly:

Of flying like a bat deep into a narrowing tunnel

Of driving alone, without luggage, out a long peninsula,

The road lined with snow-laden second growth,

A fine dry snow ticking the windshield,

Alternate snow and sleet, no on-coming traffic,

And no lights behind, in the blurred side-mirror,

The road changing from glazed tarface to a rubble of stone,

Ending at last in a hopeless sand-rut,

Where the car stalls,

Churning in a snowdrift

Until the headlights darken.

(For the complete poem, please open the All Poetry website link below).

The Dream by Edgar Allan Poe

In visions of the dark night

I have dreamed of joy departed—

But a waking dream of life and light

Hath left me broken-hearted.

Ah! what is not a dream by day

To him whose eyes are cast

On things around him with a ray

Turned back upon the past?

That holy dream—that holy dream,

While all the world were chiding,

Hath cheered me as a lovely beam

A lonely spirit guiding.

What though that light, thro’ storm and night,

So trembled from afar—

What could there be more purely bright

In Truth’s day-star?

To read more works by Edgar Allen Poe (from the text The Complete Works of Edgar Allen Poe edited by John H. Ingram) , please open the Project Gutenberg link here.

Creativity is any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain into a new one. And the definition of a creative person is someone whose thoughts or actions change a domain or establish a new one (M. Csikszentmihalyi, 1996, p.20)

Randee Lipson Lawrence (2008) explains that words alone can be limiting and limited while artistic expression can invite discussion and exploration. Paired together, words and art can be a catalyst for further creative learning opportunities. He refers to Ortega y Gasset’s (1975) insights: “one might say whereas language speaks to use of things, merely alluding to them, act actualized them” (p.147 in Lawrence, 2008, p. 67). Artistic ways of knowing can enrich students’ learning experiences, self-expression, and sense of agency. They can help learners see the world in ways that “deepen understanding of self, others, and the world around us”. Edmund O’Sullivan (2002) explains that we are at a “terminal phase” in life; we are living in a time that demands critical solutions to overpopulation, climate change, the exploitation of natural resources, natural and human made catastrophes, conflict and war, and toxic globalization that benefits a few and disenfranchises so many. Our sense of belonging to a larger stable community is eroded in the maelstrom of keeping up with change and mobility. “The wisdom of all our current educational ventures in the 20th century serves the needs of a dysfunctional industrial system. “(p.92). O’Sullivan writes that “we are living in a period of the earth’s history that is incredibly turbulent and in the epoch in which there are violent processes of change that challenge us at all energy levels imaginable. The pathos of being the human being today is that we have it within our power to make life extinct on this planet” (p. 9.). Too often, education “has been compromised by the vision and values of the market” and “in a world economy governed by profit motives, there is no place for the cultivation and nourishment of the spiritual life” (p.10).

A visionary and transformative education would embrace a new path and encourage a reverence for all life forms. It would encourage “all members of the planet to enter communities of greater inclusion. Inclusion does not entail a violation of boundaries. Inclusion means an openness to variety and difference” (p.9). Unbridled materialism could, in effect, lead to a “dulling” of the imagination. Ptak (2006) notes that strip malls, cathedrals of mass consumption and big box stores, on-line commerce, and the “gigabyte” culture threatens the creative promise and potential of vibrant and diverse communities around the world (Ptak, 2006, p.3) A transformative vision of education would encourage hope and creative problem solving. The global world we are living in challenges educators to be life-long learners who are attuned to the events, issues, and dramatic changes that are emblematic of a new epoch.

I take the view that literacy is a life-widening process rather than a life-limiting one. Reading and writing must be situated in ways that are meaningful to students and that are complemented with new forms of literacy that evolve from daily transactions between individuals, their local communities, and events in the larger global context. Literacy extends to a critical awareness of political, social, cultural, and environmental events. Along these lines, Romano (2000) emphasizes the importance of students having opportunities to read varied texts and then to create multi-genre texts that may include literary works, digital, audio, traditional graphics, and multi-media texts. Projects can integrate diaries, photographs, letters, in addition to traditional forms of writing such as exposition, description, persuasion, and narration. Literacies must also extend to imaginative and creative realms of thinking, feeling, and acting:

[Transformative] pedagogical approaches encourage self-expression, reflection, democratic discourse, and experiential learning that can result in perspective-taking and new creative insights into problem solving. Storytelling; artistic creations such as collage, sculpture, and painting; creative writing; student generated discussions; and open-ended questioning form an interest-driven curriculum where students have ‘choice and voice.’ (Magro, 2018, p.197).

Learning and literacy are interconnected; they involve a continual discovery of new understandings and ways of knowing. Literacy texts can cross disciplines, genres, and pedagogical models. In previous works, I describe various theoretical perspectives in critical literacy, arts-based education, creativity, and transformative theories of learning (Magro, 2021, 2022). Three approaches to creative literacy learning (detailed in this chapter) are particular important for Artistic Ways of Knowing (AWOK). These include storytelling; the integration of art and emotional literacy in teaching English language arts and related disciplines; and, interdisciplinary and ethnographic approaches to literacy learning. These approaches can provide opportunities for students and teachers alike to be researchers, artists, and co-learners in a dynamic process that extends beyond the classroom. Learning is both self-directed and collaborative; it is dynamic, cyclical, and taps into emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and imaginative domains of learning. Literacy can be conceptualized as a set of social practices that are often, but not always mediated by written and oral texts (Barton and Hamilton, 1998, p.9).Mass media and new technologies have changed the way that individuals develop literacy skills as they navigate between school, work, home, and community. Mathematical systems, musical notation, maps, and other non-text based images point to multi-layered and integrated literacy and language systems. There is a permeability of boundaries and a movement between boundaries so that literacy form and function are always changing and evolving.

The outcomes of art education are far wider than learning how to create or see the objects populating museums and galleries. The world at large is a potential source of delight and a rich source of meaning if one views it within an aesthetic frame of reference. It can be said that each subject studied in schools affords the student a distinctive window or frame through which the world can be viewed (Elliot Eisner, The Arts and the Creation of Mind, 2002, p.44).

Creative teaching and learning repertoires that highlight interdisciplinary and panoramic ways of knowing can be a catalyst to creative learning. In their overview of Scotland’s government initiatives to integrate creativity into all levels and curricula I education, Das Dewhurst, and Gray (2011) write about the importance of teaching for creativity with a focus on helping learners develop metacognitive abilities and skills that include: intrinsic motivation, self-direction, collaboration, flexibility, confidence, curiosity, intentionality, risk- taking and resilience. (p.5). The ability to cope with ambiguity and solve unpredictable problems with innovative are also skills associated with creativity. They refer to the UNESCO (2001) “four pillars of learning”: Learning to do; Learning to be; Learning to know; and, Learning to live together as a foundation for meaningful learning across the educational levels. Elements of creative learning can be woven throughout these learning pillars throughout an imaginative and meaningful curriculum.

Das, Dewhurst, and Gray (2011) also highlight the value of interdisciplinary thinking with a focus on integrating cognitive, social, artistic, and affective ways of knowing. Visual literacy and artistic ways of knowing can also be viewed as a way to strengthen “interpretive reasoning.” There are many consistencies and parallels between holistic learning, creative learning, multimodal literacy development, and teaching for wisdom, creativity, and intelligence (Sternberg, 2016; Sternberg and Lubart, 1995). Research studies have found that regardless of their socio-economic background, positive learning achievements were associated with learners who experienced higher levels of arts education (Bamford, 2006). Another finding from the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities (PCAH, 2011) found that “the practice of teaching across classroom subjects in tandem with the arts, have been yielding some particularly promising results in multiple-careers-learning how to ‘re-design’ oneself, locate oneself in a job market, and choose and fashion the relevant education and training”(PCAH, 2011, p. 2 cited in Das, Dewhurst, and Gray, 2011). Creativity also extends beyond the expressive arts forms (drama, music, visual art, etc.) to include a way of thinking that can lead to purposeful (and ethical) imaginative originality. Das, Dewhurst, and Gray explain that:

Originality can be expressed through writing, painting, building, thinking or even simply doing things in a manner that is distinct. The school of thought which explored the concept in relation to intellect claimed that divergent thinking is more capable of fostering creativity in a learning context. According to these researchers (Hudson, 1966), closed reasoning or convergent thinking, despite producing conventional responses, lacks the power of imagination and therefore less capable of school reform and closing the achievement gap (Das et al. 2011, p. 8).

Teaching from an interdisciplinary stance is also more than making “cross curricular links” between subjects. It involves a holistic and panoramic analysis where ideas from one or more fields of study/disciplines inform and illuminate other subject areas. Interdisciplinary thinking involves analysis, synthesis, and creative integration. An emphasis is placed on facilitating deeper level meaningful connections between and among disciplines (Das, Dewhurst, and Gray, 2011, p.8). Drawing upon John Dewey’s (1916) criticisms about the narrow classification of educational disciplines, theorists such as Hugh Petrie (1992) moved from the “essentially fragmented and sometimes disjointed nature of disciplinarity to the additive nature of multi-disciplinary engagement, the integrative aspect of interdisciplinarity and ‘the idea of the desirability of the integration of knowledge into some meaningful whole’ exemplified by transdisciplinarity” (Hugh, 1992, cited in Das, Dewhurst, and Gray, 2011, p. 8).

In The Arts and the Creation of the Mind, Elliot Eisner (2002) provides specific guidelines for interdisciplinary approaches to integrating the arts in education. Eisner explains that art education should help learners “recognize what is personal, distinctive, and even unique about themselves and their work”(44). Integrating the arts in education should “make special efforts to life experiences to aesthetic ways of knowing. Eisner asserts that:

To see the world as matter in motion, the way a physicist might, provides a unique and telling view. To see it as a historian might is to get another angle on the world. To see it from an aesthetic frame of reference is to secure still another view. Each of these views makes possible distinctive forms of meaning. Education as a process can be thought of as enabling individuals to learn how to secure wide varieties of meaning and to deepen them over time (p. 44-45).

Inviting diverse viewpoints and deepening the way individuals perceive, interpret, and understand their life worlds speaks to a major focal point in teaching and learning today. Meaningful interdisciplinary connections between subject areas to understand a holistic perspective can be made between social studies and art, for example when studying the Civil War in the United States (1861-1865). Forms of dress worn by people from different social classes could be analyzed; literature (fiction and non-fiction) can be studied to inform the social, cultural, and historical context of the civil war. Art, music, literature, and history can be meaningfully integrated to form a holistic understanding of a particular period in history (Eisner, 2002, p. 40). Interdisciplinary learning can be encouraged with thematic explorations of topics like metamorphosis. Ovid’s “Metamorphosis” can be explored through art images that depict the myths and legends featuring mythic beings, human, and deities that transform their shapes and physical identities within supernatural contexts that convey existential messages. Written in 8th CE, Ovid’s poem is written in 15 books or parts; each book chronicles the history of the world and interprets the creation of the universe (until the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BC) as a complex series of minor and major transformations. Ovid’s epic poem inspired artists and writers who provided their interpretation of famous myths such as “Daedalus and Icarus,” “Orpheus and Eurydice “and “Echo and Narcissus” in unique ways. Eisner explains further interdisciplinary connections that explore Metamorphosis:

The concept of metamorphosis, for example, can be illustrated through the way a melody is altered in a symphony, by the ways in which the demographics of an area change the terrain, and by changes in a sequence of images in film or photography. Metamorphosis is a biological concept, but its manifestations can be located in a host of other domains and disciplines. An integrated curriculum can help students see the connection between biological meaning and other meanings, artistic and nonartistic, that pertain to the concept.

Artists such as Maria Sybilla Meriam and Ernst Haeckel produced exceptional artistic images of the process of metamorphosis where caterpillars are transformed into butterflies. These art images can complement scientific and literary depictions of transformation. Problem solving and “intelligent reflection” (Dewey, 1932 cited in Eisner, 2002, p. 43) explored through the lens of multiple disciplines could be used in experiential learning projects. Designing a new park or playground could be a catalyst to perspective taking and interdisciplinary study. Eisner (2002) emphasizes that “the visual arts make visible aspects of the world—for example, the expressive qualities—in ways that other forms of vision do not. The ability to see the world in this way is no small accomplishment. It engenders meanings and qualities of experience that are intrinsically satisfying and significant” (pp. 42-43).

Helen Colby (2021) writes:

The term ‘metamorphosis’ is elusive and multi-layered. Biologically it signifies a complete change of physical form, though it also describes a change by supernatural means and can relate to the inner psychological transformations of being and identity. These aspects are incorporated into the epic poem Metamorphoses by the ancient Roman poet known as Ovid (43 BC–AD 17/18). Within this work, written in Latin around the end of the first century BC, the poet weaved stories together with themes of psychological and physical transformation. He considered timeless topics such as romantic and maternal love, pursuit and punishment, ambition and downfall.

To learn more about Ovid’s Metamorphoses, please open the links here, here. and here.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy. Public Domain.

On the island of Lesbos (Mytilene), in the late 7th century BC, Sappho and her companions listen rapturously as the poet Alcaeus plays a “kithara”. Striving for verisimilitude, Alma-Tadema copied the marble seating of the Theater of Dionysos in Athens, although he substituted the names of members of Sappho’s sorority for those of the officials incised on the Athenian prototype.

*Sappho (both c.610- died c. 570 bce) was a Greek Lyric Poet. Her poems are admired for their elegance and style. Greek lyric poet greatly admired in all ages for the beauty of her writing style. You can read more of her poems here.

In the Grey Olive-Grove a Small Brown Bird by Sappho

XV

In the grey olive-grove a small brown bird

Had built her nest and waited for the spring.

But who could tell the happy thought that came

To lodge beneath my scarlet tunic’s fold?

All day long now is the green earth renewed five

With the bright sea-wind and the yellow blossoms.

From the cool shade I hear the silver splash

Of the blown fountain at the garden’s end.

XVI

In the apple boughs the coolness

Murmurs, and the grey leaves flicker

Where sleep wanders.

In this garden all the hot noon

I await thy fluttering footfall

Through the twilight.

“My Song” by Rabindranath Tagore

the fond arms of love.

This song of mine will touch your forehead like a kiss of

blessing.

When you are alone it will sit by your side and whisper in

your ear, when you are in the crowd it will fence you about with

aloofness.

My song will be like a pair of wings to your dreams, it will

transport your heart to the verge of the unknown.

It will be like the faithful star overhead when dark night is

over your road.

My song will sit in the pupils of your eyes, and will carry

your sight into the heart of things.

And when my voice is silent in death, my song will speak in

your living heart.

Auguste Alexandre Hirsch (1833-1912), Alexandre-Auguste Hirsch – Calliope Teaching Orpheus, 1865, Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, France, Public Domain.

Key Takeaways

- Art can reflect both social and psychological perspectives.

- Each person may have their own individual interpretation of a work of art. Each person may bring their own biases, experiences, personality, values, and memories when viewing a work of art. There are myriad interpretations of works of art.

- Art can be understood from a social, cultural, and historical context.

- Different subject areas can be used to inform our understanding of art and why a particular art chose to depict individuals, society, nature, etc. in a particular way.

- Works of art may reveal the artists’ views of life; they may represent a personal journey, fears, memories, dreams, hopes, and ideals. Art may also be a reflection of the artist’s emotional state and psyche.

- Art can be a catalyst to creative learning across the disciplines further enriching reading comprehension and writing.

- Art also has a therapeutic value as it encourages individuals to express complex emotions and in the process, heal in some way. For more information please open the link here.

Please refer to the Elements of Art from the Getty Art Museum.