10.6 Artistic Depictions of The Tempest (1610-1611) by William Shakespeare

The Tempest in Art and Dramatic Verse

The Tempest (1610-1611) was likely William Shakespeare’s last play and perhaps his most original (Rouse, 1978, p. 860). This compelling play crystallizes many of the themes of life, enchantment, love, loss, death, power, innocence, revenge, atonement, and forgiveness. Supernatural elements interact with the temporal and physical domains. The natural environment is presented as a force to be reckoned with; life sustaining but unrelenting in its ability to control the fate of individuals. A work of the imagination and creative spirit, Shakespeare’s The Tempest continues to inspire. The often treacherous voyages of “discovery” which increased throughout the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in encounters with Indigenous Peoples and their lands. Rather than understanding, appreciating, and revering nature, interactions with Indigenous Peoples and their lands too often resulted in widespread conflict, warfare, disease, and colonial destruction. The Tempest is a play that also celebrates the beauty and force of nature.

The tempest which was conjured by Prospero destroyed the ship of King Alonso. Prospero sent Ariel and the spirits to create the storm; Miranda implores her father not to harm those on board. The storm forces those on board the ship to seek shelter on the enchanted island. Prospero seeks revenge from both the King of Naples and his brother Antonio who had conspired to prevent him from his role as the Duke of Milan. With magic as his power, Prospero seeks to find “poetic justice” to exact past wrongs and injustices. In the end, Prospero recognizes the limits (and harm) of his power and decides to seek reconciliation and peace.

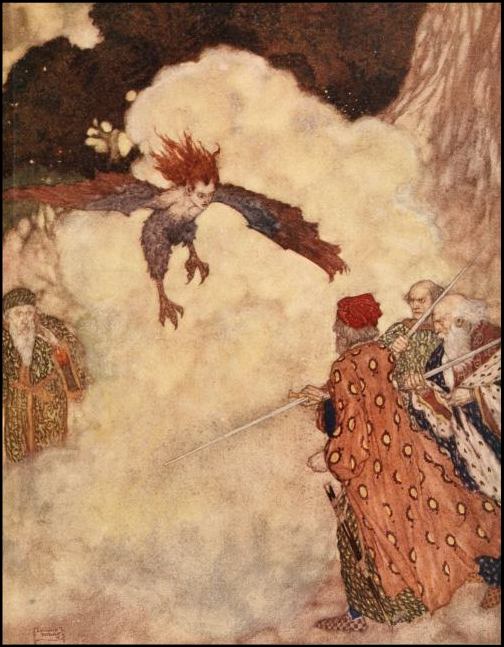

Tate Gallery Note about Henry Singleton’s work

This picture depicts Ariel, the magical spirit in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. It was first exhibited accompanied by lines from Ariel’s last song: ‘On the bat’s back I do fly, After summer, merrily.’ Singleton’s decision to paint this entertaining and theatrical subject was a response to popular tastes of the time. The artist had begun his career as a promising history painter but many felt he did not realise his full potential (The Tate Gallery, London, England).

Ariel, the magical spirit, is bound in service to Prospero:

All hail, great master! Grave, sir, hail!

I come,

To answer thy best pleasure: be’t to fly,

To swim, to dive into the fire, to ride

On the curl’d clouds, to thy strong bidding task

Ariel and all his quality” (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 1.2)

In response to Prospero’s bidding, Ariel creates havoc to cause the shipwreck. Prospero’s plan to seek vengeance upon his brother will soon be realized. Ariel is also enslaved and is forced to follow through on his/her master’s demands:

To every article,I boarded the king’s ship; now on the beak,

Now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin,

I flamed in amazement: sometime I’ll divide

And burn in many places; on the topmast,

The yards and bowspirit, would I flame distinctly,

Then meet and join. Jove’s lightnings, the precursors

Of the dreadful thunder-claps […] (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 1.2).

Additional Resources

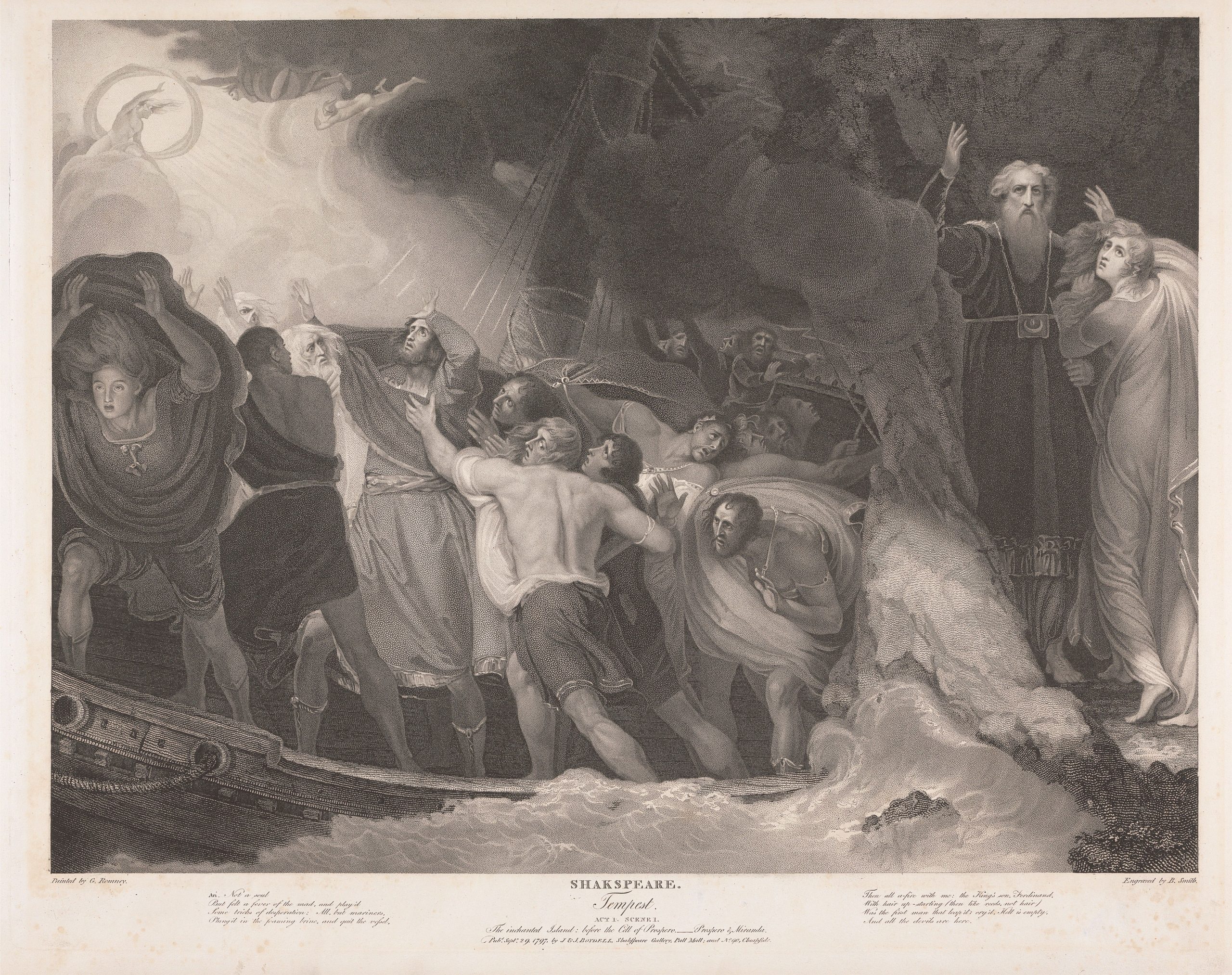

To read an essay about the artist George Romney and his painting of The Tempest, please open the link here.

“The Island is Full of Noises”

[…]the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 3.2).

Additional Resources

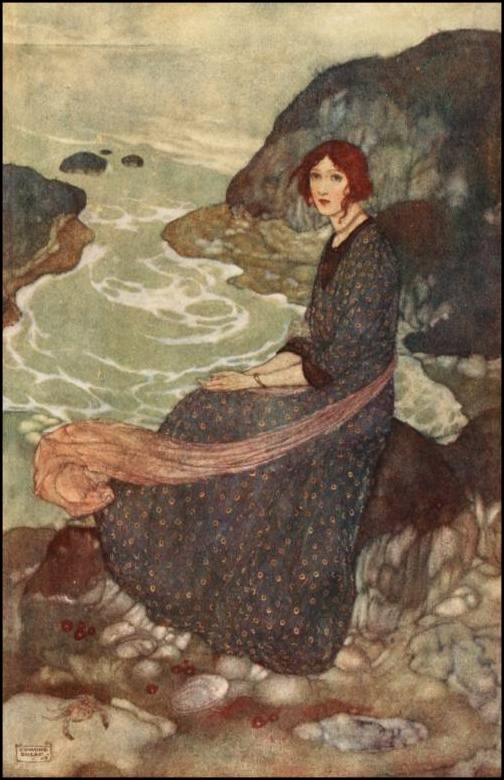

“O brave new world that hath such people in it” (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 5.1).

“If by your art” (Miranda speaking to her father Prospero, The Tempest).

If by your art, my dearest father, you have

Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them.

The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch,

But that the sea, mounting to the welkin’s cheek,

Dashes the fire out. O, I have suffer’d

With those that I saw suffer: a brave vessel,

Who had, no doubt, some noble creature in her.

Dash’d all to pieces. O, the cry did knock

Against my very heart. Poor souls, they perish’d. (Shakespeare, 1610-1611/1978, The Tempest, 1.2)

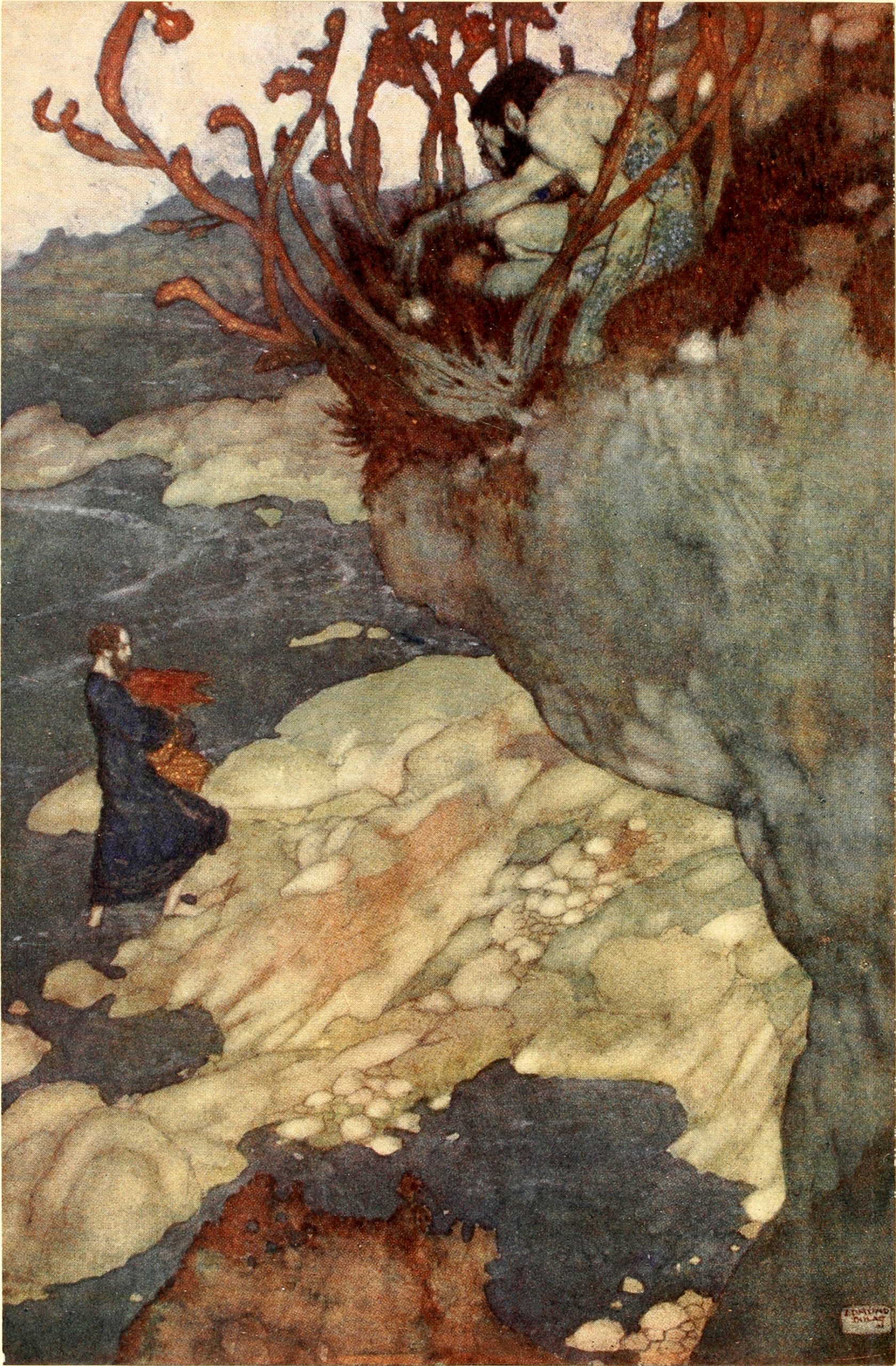

“This Island’s Mine” (Caliban to Prospero, The Tempest)

This island’s mine by Sycorax, my mother,

Which thou tak’st from me. When thou cam’st first,

Thou strok’st me and made much of me, wouldst

give me

Water with berries in ’t, and teach me how

To name the bigger light and how the less,

That burn by day and night. And then I loved thee,

And showed thee all the qualities o’ th’ isle,

The fresh springs, brine pits, barren place and

fertile.

Cursed be I that did so! All the charms

Of Sycorax, toads, beetles, bats, light on you,

For I am all the subjects that you have,

Which first was mine own king; and here you sty me

In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me

The rest o’ th’ island (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, I. 2).

At the end of the play, Prospero admits his failings and renounces magic; he “releases” Ariel and Caliban and seeks to reconcile with his brother.

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have ’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now ’tis true

I must be here confined by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got

And pardoned the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell,

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 5.1)

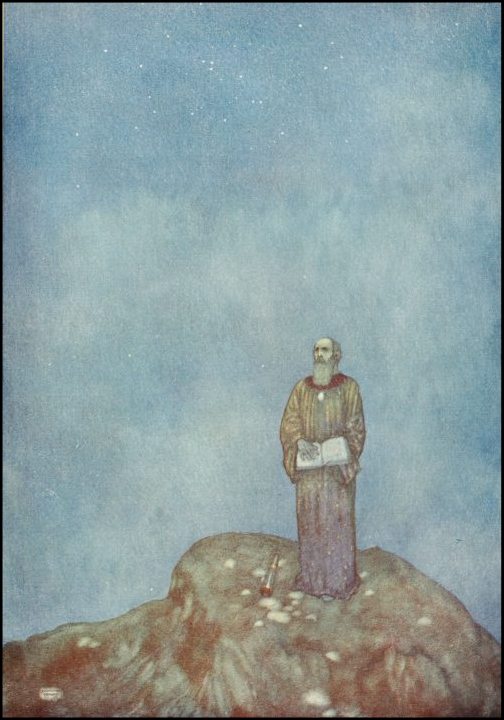

A Closer Look at Edmund Dulac’s imaginative illustrations for The Tempest.

Prospero:

[…] And by my prescience

I find my zenith doth depend upon

A most auspicious star’ (Shakespeare, 1610-1611, The Tempest, 1.2).