Chapter 8: Encouraging Emotional and Social Literacies through Art: Exploring Emotions

A work of art which isn’t based on feeling isn’t art at all. (Paul Cézanne).

It is with the reading of books the same as with looking at pictures; one must, without doubt, without hesitations, with assurance, admire what is beautiful (Vincent Van Gogh).

If you truly love nature, you will find beauty everywhere (Vincent Van Gogh).

Emotional and Social Literacies

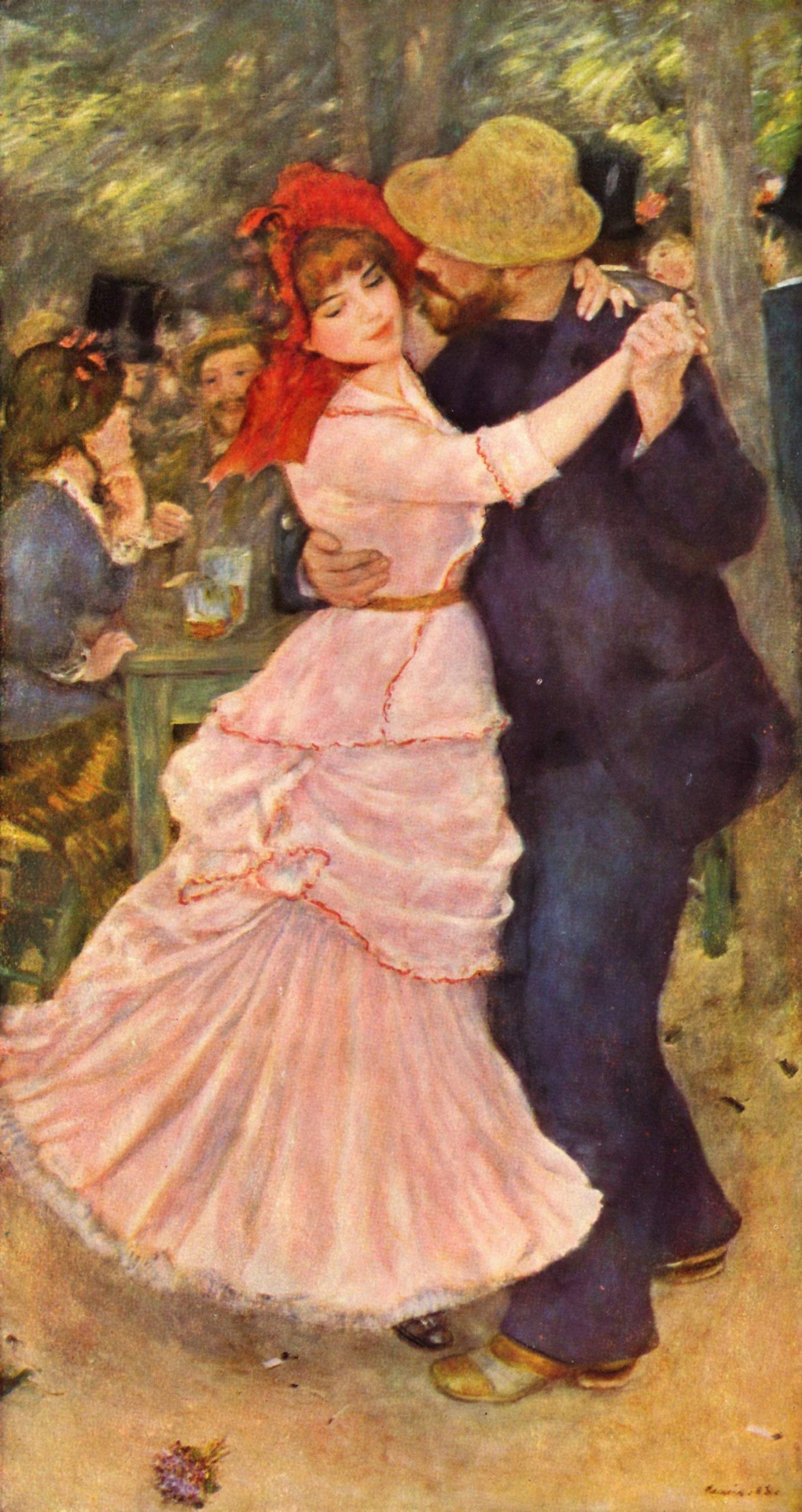

Courtesy: By Pierre-Auguste Renoir – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=158172

Introduction

This chapter will explore the theoretical and practical aspects of integrating emotional, social, and transcultural literacies within the broader context of artistic ways of knowing. The art images and related texts featured in this chapter can be viewed from a social, emotional, and psychological lens. As the previous chapters suggest, visual art and related literary texts can evoke and inspire a range of emotions. I will draw from my own research working with English, drama, biology, and social studies secondary school and adult literacy teachers in exemplifying various dimensions of teaching emotional and cultural literacy.

Today’s educators are challenged to acknowledge the multiple dimensions of literacy, including the social, emotional, economic, technological, and aesthetic literacies, and the potentially creative ways that they can be integrated at all educational levels. The previous chapters detail the way in which conceptions of literacy and learning have moved beyond developing fundamental skills in isolated content areas such as mathematics, geography, and English and into essential skills for living more meaningfully. As literacy educators, we recognize that knowledge construction has expanded to include not only printed texts, but dynamic texts that are supplemented with film, news media, and song. Teachers today are challenged to be flexible in their ability to shift from traditional literary practices to instructional strategies and modalities of knowledge construction that draw upon multiple literacies. Often, choices in texts and learning strategies are being reformatted and reconceptualized to address the changing needs of youth and adolescents. Creative, social, and pedagogic challenges can be met when teachers encourage literacy from diverse sources.

Building on Gardner’s (1983) research into multiple intelligences, Goleman’s books Emotional Intelligence (1995) and Working with Emotional Intelligence (1998) emphasize that qualities such as empathy, self- awareness, managing stress and problem solving, and interacting effectively with others are essential “life skills” that may be more important than traditional indicators of intelligence and academic achievement in contributing to a fulfilling life. Literacy learning can provide opportunities for students to develop self-awareness and empathy. Xerri and Xerri Agius (2015) write that empathy can “bridge gaps” between persons and cultures. “Empathy is a means of cognitively and emotionally understanding the experiences undergone by the other while engaging in self-awareness” (p. 71). Empathy can help our students develop a greater appreciation of the transformative power of literature, art, and culture. Goleman’s (1995) emotional competence framework includes the following personality characteristics:

- Self-awareness, or recognizing one’s emotions and their effects on others, and the ability to assess one’s strengths and limitations;

- Empathy, which refers to an awareness of others’ feelings, needs, and concerns and the ability to understand others’ feelings and perspectives;

- Self-regulation, or managing one’s internal states, impulses, and resources, and linked to personality traits such as conscientiousness, adaptability, trust worthiness, and the ability to explore new ideas and information;

- Motivation, referring to the emotional tendencies that guide short and long term goals and behaviours that include traits such as commitment, initiative, optimism, and a drive for achievement; and

- Social skills, which includes effectiveness in collaboration and cooperation, active listening, the art of getting along with others, and leadership. (Goleman, 1998, pp. 26-27)

Salovey and Meyer (2014) write that “emotionally intelligent individuals accurately perceive their emotions and use integrated, sophisticated approaches to regulate them as they proceed toward important goals” (p. 202). Earlier, Vygotsky (1987) highlighted the way perceptions, memories, thoughts, emotions, and imagination can influence action. He recognized the importance of teachers understanding the complex interplay of emotion and logic. In developing empathy, self-awareness, and imaginative thinking, children and youth will be better able to solve crises and challenges that are part of their life trajectory. In The Psychology of Art, Vygotsky analyzes how plays like Hamlet can be used to help readers and viewers connect emotion to the artist and to the larger culture. “Art becomes our emotional rehearsal for the larger social experiences of our lives, culture, and epoch” (Mack, 2012, p. 21). Emotional and social intelligence can guide a person’s thinking and actions. Over the past two decades, educators have applied their ideas and developed innovative programs that include a social emotional intelligence curriculum (Mack, 2012; Magro, 2009). Exploring literature and non-fiction through the lens of emotional intelligence can challenge students to make valuable connections between the text and their own lives. In identifying with a main character, students have the opportunity to explore the way they might solve a particular crisis in their lives.

The following art images exemplify the way in which various artists depict varied emotional states.

Courtesy: By Sofonisba Anguissola – Poster.us.com, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22040095

Courtesy: By Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret – https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2012/19th-century-paintings-n08847/lot.70.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93178252

Art and Emotion

Art can be viewed as a powerful force for communication. Art images that are completed with poetry and narratives can challenge individuals to explore the range of emotion that include curiosity, confusion, anger, sadness, joy, and surprise. Individuals can learn more about their own emotional states through works of art. Further thinking and learning can occur when educators provide multimodal learning experiences (for more information about art and emotion, please open the link below). Robert Plutchik’ s (2001) “Wheel of Emotion” can be a useful graphic for students to use when identifying specific words that convey a range of emotions. https://www.6seconds.org/2022/03/13/plutchik-wheel-emotions/.

Wheel of Emotion by Robert Plutchik (2001). Wikipedia. Public Domain.

Reading Emotions in Paintings

Based on Robert Plutchik’s (2001) Wheel of Emotions, students can develop their skill in understanding and “reading” emotions of individuals depicted in artistic works. Gradiations of emotions can be analyzed and explored (sadness vs. worry or desperation, joy vs. exhilaration). Contrasting emotional states such as calm expression vs. anxious and worried could be analyzed). Understanding the motivation behind the character’s/sitter’s expression could be researched. This skill can then be further applied when students are challenged to assess characters in novels, short stories and drama. Emotional Intelligence (EI) involves the “ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; the ability to access and or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth” (Sternberg, 2003, p. 38). R.J. Sternberg (2003) draws upon research by Mayer and Gehr (1996) who found that “emotional perception of characters in a variety of situations” is correlated with EI skills such as awareness, empathy, and emotional openness.

Courtesy: By Crijam – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98801236

Courtesy: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Pakarinen. August and Lydia Keirkner Fine Arts Collection. “https://www.kansallisgalleria.fi/fi/object/448509” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: By Alice Pike Barney – http://americanart.si.edu/mycollection/mobject.cfm?section=&scrapbook=1464&page=1&objectID=12224, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18392100

Art and Emotion

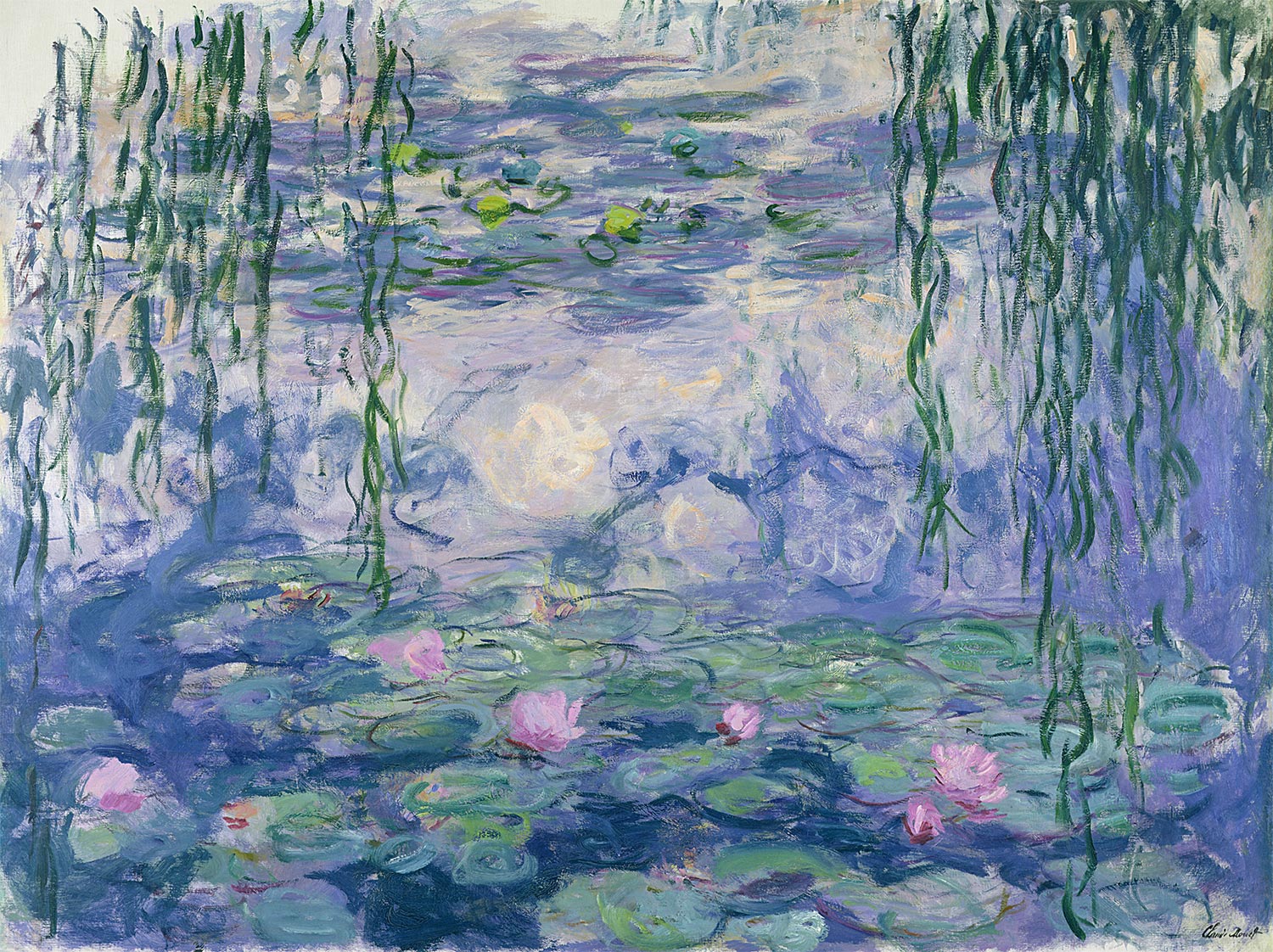

Art can be viewed as a powerful force for communication. Art images that are completed with poetry and narratives can challenge individuals to explore the range of emotion that include curiosity, confusion, anger, sadness, joy, and surprise. Individuals can learn more about their own emotional states through works of art. Further thinking and learning can occur when educators provide multimodal learning experiences (for more information about art and emotion, please open the link below). Robert Plutchik’ s “Wheel of Emotion” can be a useful graphic for students to use when identifying specific words that convey a range of emotions. https://www.6seconds.org/2022/03/13/plutchik-wheel-emotions/. The art works of Frieda Kahlo, Vincent Van Gogh, Edvard Munch, and Leonardo Da Vinci are known for their powerful emotional impact on viewers. A exploration of art from an emotional/psychological angle can encourage creative and reflective learning on the role that emotions play in life. A landscape by Claude Monet might evoke a sense of reflective calm or a sense of joy found in nature. Briton Reviere’s landscape with the polar bear overlooking a scene can evoke awe and wonder. Rembrandt’s “The Return of a Prodigal Son” is a painting where complex emotions of shame, relief, and curiosity are displayed. While the artist might express a particular point of view, the viewers also experience emotion. The emotional expressions of the sitter’s in Giovanni Boldini’s paintings might be a catalyst to writing an interesting short story revolving around the characters. Pascal Dagnon Bouveret’s paintings of the characters in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet reveal scope and emotional intensity. Ophelia’s anguish is revealed in her eyes, for example. Bouveret’s art in Hamlet can be explored from a psychological and emotional angle. Carolyn Schlam (2021) emphasizes that colour, lines, shape, light, point of view, atmosphere, and the emotional expression of the sitters in a particular painting are all factors that influence our own emotional responses to the art. The artist might render a particular subject realistically, stylistically, or abstractly. Through art, human experience can be enriched and greater understanding between individuals can occur:

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, then, by means of movements, lines, colours, sounds, or forms expressed in words, so to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art.

Art is a human activity, consisting in this, that one man consciously, by means of certain external signs, hands on to others feelings he has lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings, and also experience them. (Leo Tolstoy 1904, p. 50)

Leo Tolstoy and Art

To read the complete book “What is Art?” by Leo Tolstoy (1904), please open the link here.

Additional Source: Pierre Fasula : What is the connection between artworks and emotions?

Courtesy: By Giovanni Boldini – Il Cricco Di Teodoro Itinerario nell’arte Dal Barocco al Postimpressionismo Versione gialla, p. 1617, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58364169

Excerpt from “The Rich Boy” by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940)

“Let me tell you about the rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and the it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are. They are different. The only way I can describe young Anson Hunter is to approach him as if he were a foreigner and cling stubbornly to my point of view If I accept his for a moment I am lost—I have nothing to show but a preposterous movie…”

For the complete story “The Rich Boy”(1924) by F. Scott Fitzgerald please open the link here.

Courtesy: By Giovanni Boldini – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5066064

Courtesy: By Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret – Christie’s, LotFinder: entry 5127422 (sale 2035, lot 222, New York, 22 October 2008), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46250094

Courtesy: By Edward Burne-Jones – Scanned from Wildman, Stephen: Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, ISBN 0870998595, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2218884

Courtesy: By John William Waterhouse – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1064193

To read the poem “The Lady of Shallot” by Sir Alfred Lord Tennyson, please open the link here.

Courtesy: By Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret – https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2013/19th-century-european-art-n09034/lot.53.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93178283

Different landscape paintings can also evoke emotions in viewers. What emotions do you feel when you see a particular work of art?

Courtesy: By Claude Monet – musée Marmottan-Monet [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79058628

Resource

For more information about art and emotion please open the link below.

Courtesy: By Briton Rivière – Art UK, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91865474

Courtesy: By Rembrandt – 5QFIEhic3owZ-A — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22353933

Just as it is important to recognize the value of cultivating emotional literacies, it is vital for educators to examine the barriers that prevent individuals from developing emotional literacy. Giroux (2005) asserts that the complex interplay of the psychological, emotional, spiritual, and cultural dimensions of learning is rarely addressed in traditional classrooms. Moreover, youth today are increasingly excluded from meaningful participation in our society. He emphasizes that as a symbol of the future, children “provide adults with an important moral compass and a power referent for addressing war, poverty, education, and other social issues, and yet their voices are not being heard” (p. 252). Rather than critically addressing the systemic sources of societal dysfunction, youth are often scapegoated for societal problems such as joblessness, homelessness, and violence. In addition, “the marketplace only imagines [youth] as consumers or billboards wearing branded clothes, accessories, and other items in order to sell sexuality, beauty, music, sport, clothes, and a host of other consumer products” (p. 25). Despite the “anti-bullying” programs and other initiatives to promote cultural inclusion, many youth feel alienated, misunderstood, and disengaged from meaningful participation in society. He writes that there is “the growing isolation of children as they spend increasing periods of time in front of screens, learning the literacy of violence in video games, learning the literacy of insensitively from TV ‘reality shows’ or learning the literacy of consumerism from an endless bombardment of advertising” (Giroux, 2005, p. 116). From Giroux’s transformative learning perspective, education needs to provide meaningful opportunities for students to gain vital literacy skills in order to understand the world around them. “Education is not only about issues of work and economics, but also about questions of justice, social freedom, and the capacity for democratic agency, action, and change” (p. 116). Integrating art, photography, poetry, and drama can provide valuable opportunities for creative expression, particularly for students who may be struggling with anxiety and feelings of isolation.

The Literacy Teacher as Challenger, Cultural Guide, and Researcher

Daniels (2010) emphasizes that motivation among learners is enhanced when they feel a sense of autonomy or control in their lives and when they feel connected to the class in the school. Their sense of self-direction and motivation is increased when students possess the skills necessary to meet the challenges in life. Motivating teachers create lessons that encourage students to make meaningful connections between the texts and their own lives. Thinking of students as “designers” and “advocates” for their own rights and the rights of others reframes the educational process. Effective learning occurs when teachers are able to create a psychological climate that encourages self-expression, an exploration of diverse viewpoints, reflective dialogue, and creativity. Literature circles, journal writing, self-directed research projects, and individual or group presentations are some of the strategies that can facilitate experiential learning (Magro, 2008). Working with adult literacy learners, Jarvis (2006) used literary texts like Bronte’s Jane Eyre as a way to encourage critical reflection and transformative learning. She writes that “students explored the conflicts between their own perspectives on issues such as marriage, immigration, or feminism, and the perspective in the texts they encountered” (p. 71). Creating writing gave her students “the space to imagine alternatives to the kinds of discourses about women’s lives and relationships…the object was always to have a critical dialogue–a dialogue with the text itself, between students, with imagined possibilities” (p.71). The challenge for teachers is being able to “demystify” literature and bring powerful social and psychological themes to the foreground in meaningful ways to diverse student groups.

Jane Eyre has also been illustrated by many artists and a comparative analysis of different artistic depictions of the novel could be a valuable inquiry project. The landscape of the North York Moors in south west England can be studied with an emphasis on the way the geography and climate can establish the mood or tone of a literary work like Jane Eyre. Further research into the way women were depicted in 19th century art could provide insights into the social and cultural expectations for women in different cultures. More information about 19th Century portraits of women can be found here.

John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) (style of) – Roche Abbey, Yorkshire – 515731 – National Trust By Anonymous. Art UK, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97547286

Integrating emotional, social, and cultural intelligence into the English language arts curriculum challenges teachers to critically reflect on and to explore their own values, beliefs, and ideals that guide their practice (Magro,2003; 2012). For example, to what extent do teachers view the literacy curriculum as a base that can potentially help their learners develop both academic and emotional competencies? Are there particular texts that are more effective in fostering emotional literacies? If so, which ones? Are there preferred teaching and learning strategies that can maximize emotional intelligence (EI) competencies. Gee (1992) writes that English teachers stand “at the very heart of the most crucial educational, cultural, and political issues of our time” (p.60) and that while they can see themselves as “language teachers” with no connection to political and social issues, an alternative is that they can explore their role as persons who “socialize learners into a world view that must be looked at critically, comparatively, and with a constant sense of the possibilities for change” (p. 60). Novels, drama, poetry, non-fiction, digital texts, art, and other media are not taught solely with the aim to deconstruct and to analyze isolated literary components, but they are explored with the intent to help learners understand themselves and the world around them in a new way.

Teachers’ Creative Perspectives

In a qualitative study looking at the way twelve English teachers conceptualized teaching and learning, Magro (2003) found that while the teachers did not directly state that they were integrating “emotional intelligence” into their teaching, many of the teaching and learning strategies that they applied reflected, in essence, themes that highlighted self-awareness, cultural intelligence, and an appreciation of social and global issues. Choice, accessibility, and the “demystification” of literature were themes that surfaced in the interviews with the teachers in this study. Some of the teachers identified with the role of an advocate, cultural guide, challenger, and seeker when asked to elaborate on the role or image that came to mind when they reflected on their own teaching. A number of the teachers also wrote poetry, fiction, and non-fiction and had published their work. Martin, a senior high teacher specializing in literature and drama, explained that he wanted to “demystify” literature. He commented that:

A number of books, essays, and plays that we explore deal with human interests. A common theme is self-development and self-discovery…the idea of characters going through stress and disappointment in life appeals to some of my students who are facing similar situations. They can explore solutions to their own problems in life with the text as a starting point. (Magro, 2003, p. 27).

Stephan, a teacher in a large urban inner city high school described the value of helping reluctant or struggling readers and “at-risk” older teens read a range of fiction and non-fiction texts that focus on themes such as loneliness, peer pressure, family, relationship building, and the future. He emphasized the importance of choice, creative writing, and the value of integrating life skills across the disciplines:

Writing is an act of seeing. I try to encourage my students to be good observers. Poetry allows my students to articulate their experiences and in the process heal in some way. Many of my students are burdened by terrific emotions. I think that the whole idea of teaching literature and creative writing is to inform, uplift, and serve as a useful psychological and spiritual guide. (Magro, p. 27)

Psychology, cultural studies, sociology, and world issues can be integrated in teaching English language arts. Themes exploring the wages of war, the price of freedom, perception, identity, and community can be creatively analyzed with diverse teaching and learning strategies. Stephan highlighted the role of “powerful” literature and non-fiction to inform, uplift, and ultimately transform life experiences. A greater understanding of human nature and the ability to solve problems can emerge:

The human question … who one is and what makes other people tick and so on is a never ending process. Literature also provides shape and form to life’s questions. That’s what keeps people reading. My approach to teaching involves this exploration. I have a desire to make shape out of different facts. Unlike other kinds of teaching where the curriculum may be very set and specific, there is an element of discovery in teaching English. Freud studies literature as a way of understanding personality and motivation. There is something bigger than an academic discipline in studying literature. We all have a narrative to tell. At its basic level, literature exists to help people understand themselves and the world. (Magro, 2003, p. 27)

Stephan used texts such as Wiesenthal’s (1976) The Sunflower to explore essential questions about the limits and possibilities of forgiveness and compassion. The students were asked to write about a situation in their lives where they had forgiven someone for betraying or hurting them. Perspective-taking can be explored in The Sunflower when students read the responses to Wiesenthal’s question: A dying Nazi soldier asks for your forgiveness. What would you do? The responses are made by individuals such as The Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, and other well-known world leaders. The responses in Stephan’s class were shared and new insights into the nature of human compassion were gained. As a published poet, Stephan encouraged his students to read varied poetic forms such as ballads, free verse, and sonnets; he then challenged his students to write their own poetry. Students were given opportunities to draw/create their image of peace. Alluding to William Wordsworth’s insight that poetry is “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” Stephan’s students wrote about topics meaningful in their own lives: the experience of racism, life without parents and living in foster homes, financial hardship, and the desire to move ahead in life and not be burdened with depression and anxiety. In many ways, he viewed his teaching as a type of therapy for students struggling with identity and self-esteem challenges. The class poetry anthology “Awareness” integrated classic poems students’ own contributions (poems, art work, etc).

Stephan explained that his students valued literary and non-fiction works that portrayed psychological journeys that in some way mirrored the conflicts that they were experiencing. He referred to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road as a way for students to explore psychological journeys, identity, self-awareness, and resilience amid tragedy. McCarthy’s novel centres on the journey of survival of a father and son in post-apocalyptic America. Along these lines, Gilbert (2012) analyzes McCarthy’s The Road from a psychosocial perspective. Maslow’s (1987) Hierarchy of Needs can become a framework for investigating the heroic quest of both the father and son in the novel; discussions around physiological needs, safety, love and belonging, self-esteem, and the ability to draw upon one’s resilience in order to survive in a hostile environment that is devoid of humanity, nature, and order make this novel a compelling choice for senior high students. Text-to-text links can be made with novels such as Golding’s Lord of the Flies, T.S. Elliot’s “The Wasteland”, Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, and Jack London’s To Build a Fire. Students can examine the way personality traits such as “resourcefulness”, “intelligence,” and “resilience” can be applied to the continual pursuit of food and shelter. The bond of love between the father and son is stronger than the continual trials that they meet along the road of an environment depleted of humanity and natural resources. In a situation of crisis, what moral or ethical framework would guide your behaviour? How well would you survive if you were in a situation similar to that of the father and son in The Road? What would you be willing to do to survive? What skills, talents, and resources would you need? What barriers stand in the way of survival? The Road is also a timely novel that can give students an opportunity to explore the consequence of war and environmental/planetary devastation (Gilbert, p.43). Photographs and art images that complement different scenes in the novel can add additional depth to the novel study.

Emily, a Grade 12 teacher in a large secondary school in Winnipeg, shared her approach to teaching from a social justice stance. As a lead teacher with the international organization UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) Associated Schools Network, she explained how important it is for students to understand a connection between their own lives and the larger world. She explained that teaching for social justice aimed at both personal and global change.

The quotation that best sums up the UNESCO themes is from Mahatma Gandhi who said ‘Become the change you want to see.’ Learning to know, learning to do, learning to be all that one can be, and learning to live together with peace and planetary sustainability are goals of the UNESCO network. I use these themes in designing my teaching units” (Magro, 2013, p. 49).

The texts that Emily’s students read are used in interdisciplinary ways to bridge literature, psychology, sociology, and history. While students have choices in terms of reading and project work, there are “anchor” texts that form the basis of exploring topics such as racism and stereotyping. For example, she explained that Sherman Alexie’s (2007) popular novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian can be used to challenge negative cultural stereotypes and racism toward First Nations People. While set on a reservation in Spokane, Washington, USA, Emily tries to make connections between the American and Canadian cultural contexts. Understanding the cultural and historical factors that forced First Nations People in North America to life on a reservation (or a reserve in the Canadian context), the loss of one’s language, culture, and lifestyle, and the escape of desperation through alcohol and other substances, can be explored through a complex and critical lens if the novel is taught in an interdisciplinary format that incorporates Aboriginal Studies, Psychology, History, and Literature. Awareness of systematic injustices toward cultural minorities could lead to transformative learning. In recent years, for example, the impetus to find out the source of the murdered and missing Aboriginal women in Canada has been at the forefront of movements such as Idle No More that demand restorative justice and truth (Scott, 2007). Novels such as Beatrice Mosioner’s (2008) In Search of April Raintree can be used in conjunction with the Alexie text as examples of the challenges faced by adolescent Aboriginal girls growing up amid family fragmentation and chaos. What has changed among First Nations People in terms of human rights, access to education, family life, and career fulfillment? What has stayed the same and why? Emily, who taught in a school with a large First Nations population in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, felt that the students resonate with this text in examining pressing problems such as poverty, the tragic outcome for individuals who lived through the residential school system, societal marginalization, systemic violence, addictions, family fragmentation, suicide, and the loss of language and identity:

The Alexie book is powerful and sad but at the same time it is hopeful, humorous, and gives my students a platform to discuss the cultural stereotypes and racism they have experienced. The hero of the book is trying to make a better life for himself amid the chaos and family tragedies. We make connections between the 7 Generations series by the Manitoban writer David Robertson, historical documents, and then the students reflect on the ways they have experienced racism and the way it interfered with their plans for the future. I want to find ways of dialoguing that enable students to see beyond themselves in more reflective and hopeful ways. How can we help out students navigate the dangers? Emotionally and cognitively, we are bombarded with images and information that many people do not question. It is like a Pandora’s Box. We do not know how each student is interpreting the messages—whether these messages are from Facebook, other social media, or the larger world around them… For many of our students, a piece is missing in their lives and they have experienced trauma. Some days I feel more like a counselor and parent to my students. I feel that an effective literacy teacher is like a person with a key who can open new doors and opportunities for students (Magro, 2013, p. 54).

A starting point for integrating emotional and social intelligence more intentionally within English language arts would be for teachers to examine their own personal philosophy of teaching. Too often the perspectives and philosophies of teachers remain tacit and not clearly understood. Teachers are rarely given opportunities to reflect, for example, on the links among the beliefs, values, and ideas that guide their practices and their choices of curriculum, their preferred teaching strategies, and the ways they assess student learning.

Related multi-genre reading and writing projects enable students to incorporate personal narratives, interviews, and social commentaries into their work. In reading a classic play like Henrik Ibsen’s (1895) A Doll’s House or modern classics like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (1925) The Great Gatsby, students can explore the similarities and differences of values, lifestyles, poverty, and wealth, and the social roles of women and men from a historical and a cultural frame. Students can become active researchers and seekers of knowledge as they broaden their understanding of the social problems faced by individuals today. Reading strategies that involve helping students make predictions, annotate difficult passages, and create glossaries for challenging words can make texts more accessible.

Integrating the dramatic arts into the curriculum is also a valuable way to help students understand volatile and controversial issues such as youth gangs, bullying, and homelessness. Orzulak (2006) writes that “weaving empathy into a lesson is particularly important when dealing with complex topics….The arts can help teachers explore potentially volatile topics with the students in a free yet safe environment” (p. 82). For example, students can write, read, and act out scripts and plays that focus on themes relevant to their own lives. Baer and Glasgow (2008) provide an example of using process drama to highlight the theme of bullying that surfaces in young adult fiction like Nancy Gardner’s Endgame and Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War. They cite Schneider and Jackson, who write that “process drama is a powerful role-play and problem -solving activity that encourages the creation of imaginary, unscripted, and spontaneous scenes” (p. 83). Active visualization, dialogue, reflection, writing, and performing are some of the ways students are able to make text-to-self and text-to-world connections. Creating Readers’ Theatre versions of powerful scenes from the novel can encourage a deeper level of awareness of the dynamics of power in bullying. Students can also create visual collages of the books/plays they are reading.

Johnson, Augustus, and Agiro (2012) examine the way media literacy and classic plays like William Shakespeare’s Othello can be used to explore bullying and its impact on self-esteem. Their article synthesized the work of a ninth-grade Advanced Language Arts Class in the rural Midwest, consisting of a rural-suburban student population with approximately 800 students in grades 9 through 12. Part of the students’ projects involved analyzing the media messages in Jean Kilbourne’s documentary “Killing Us Softly.” In particular, students were asked to analyze the way children are depicted in the media. “Girls are typically portrayed passively, and boys actively; boys are typically standing or taller than girls, unless ethnicity comes into play, in which case the child of color is often seated or shorter than the white child” (p. 57). In researching bias in contemporary media, students were then challenged to explore related themes in Othello. The concept of “harmful persuasion,” was then applied to Iago’s negative influence on Othello. Like Shakespeare’s famous villain Iago, a key goal of advertising is to create a climate where fear and insecurity influence a person to buy a particular product. Before reading the play Othello and viewing the film with Laurence Fishburn as Othello and Kenneth Branagh as Iago, students completed a survey asking them to analyze the way conflicts are portrayed in the media; they were asked questions that focused on negative stereotypes, deception, race, gender, personality, and power. Students were asked to delve more deeply into psychological and social dynamics of jealousy, rumour, gossip, bullying, group conformity, and the bystander effect. Students could link the themes in Othello with contemporary research studies, art, films, Internet sites, and so on. They could present their research findings in the form of an artistic image accompanied by an explanation, a poster, a website, a poem, or a speech. Socratic seminars and dramatic presentations were also included as follow-up activities. Students could further explore how they could counteract the harmful effects of the Iago’s of the world—“whether these conflicts are presented by people, images, or words” (p. 60). Activities like these set the foundations to critically examine the literature, the media, and the conflict in their own lives. Students can gain an appreciation of the way “classic texts” can have an impact on their lives today.

Developing Cultural Intelligence with Powerful Texts and Creative Teaching Strategies

Intercultural competence is a vital personal and social skill that teachers need in today’s culturally-diverse classrooms. Self-awareness, empathy, openness to and an appreciation of diverse cultures, effective listening skills, and a tolerance for ambiguity are just some of the characteristics scholars have associated with intercultural competence (Magro, 2012). Taylor (2002) describes intercultural competence as “a transformative process whereby the [individual] develops an adaptive capacity, altering his or her perspective to effectively understand and accommodate the demands of the new culture; he or she is able to actively negotiate purpose and meaning” (pp. 156-157). Consistent with this, Bennett (2007) describes the multicultural person as:

One who has achieved an advanced level in the process of becoming intercultural and whose cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics are not limited but are open to growth beyond the psychological parameters of any one culture. The intercultural person possesses an intellectual and emotional commitment to the fundamental unity of all humans, and at the same time, accepts and appreciates the differences that lie between people of different cultures. (Gudykunst and Kim, 1984 cited in Bennett, 2007, p. 9)

The intersection of race, ethnicity, nation, class, religion, and gender can be explored through an examination of world literature (Carey-Webb, 2001; Arias, 2007). Finkle and Lilly’s (2008) Middle Ground provides teachers with sample lessons for teaching literature such as Khalid Hosseini’s The Kite Runner from a multicultural perspective. These authors note that all too often, world literature courses are not offered to students until they are in high school and then, they are usually an elective. Finkle and Lilly (2008) emphasize that students’ exploration of multi-ethnic identity, and their need for self-examination in terms of the ‘other’ should start earlier on in their educational experiences. Given the growing numbers of North American students from Middle Eastern, Asian, and African backgrounds, curriculum choices representing different cultures, experiences, and people should be provided. Societies in these parts of the world are also multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multicultural, and multilingual, yet generalizations are often made about individuals and cultures. Bennett (2007) writes that in developing pedagogy for multicultural education, there should be “the movement toward equity or equity pedagogy, curriculum reform, or a rethinking of the curriculum so that it represents multiple narratives and perspectives; helping students gain multi-cultural competence” (p. 4). This would provide a foundation for teaching social justice issues and discrimination of all kinds such as racism, sexism, and classism (Bennett, 2007, p. 4).

A multicultural curriculum that includes texts that represent different voices from an international perspective can be developed as a way to build intercultural intelligence. As our classrooms today are becoming more multi-ethnic and multicultural, the roles and responsibilities of teachers have also become more complex. Knowledge of other cultures, traditions, languages, and customs that mirror the diversity of the world will equip both teachers and students with the skills needed to navigate these micro- and macro- changes. “Adding an international dimension to subjects and encouraging students to reach out to peers in other countries are powerful ways to make the curriculum relevant and engaging to today’s youth” (Stewart, p. 10). Sefa-Dei (2002) explains that education provides new ways to help students integrate history, place, and culture. He asserts:

The individual as a learner has psychological, emotional, spiritual, and cultural dimensions not often taken up in traditional processes of schooling. Holistic education that upholds the importance of spirituality recognizes this complexity by speaking to the idea of wholeness. Context and situation are important to understanding the complex wholeness of individual self or being. The individual has responsibilities to the community and it is through [holistic] education that the connection between the person and the community is made (pp. 124-125).

Teachers can assist their students in developing the creative, analytical, and intellectual skills to clarify, to justify, and to realize a more positive vision of the future (Sternberg, 2003). Teachers from culturally- diverse backgrounds and curricula that represent the diversity of our students can enhance motivation and learning. Sefa-Dei (2012) further observes that a school system that fails “to tap into youth’s myriad identities…is short-changing learning. Identity is an important site of knowing. Identity has in effect become a lens of reading one’s world…the role and importance of diversity in knowledge production is to challenge and subvert the dominance of particular ways of knowing” (pp. 119-120). He emphasizes that a “pedagogy of language liberation” would empower learners to tell their stories and learn about their heritage, history, and culture in interconnected ways. For Sefa-Dei, spirituality “is about a material and metaphysical existence that speaks to an interconnection of self, community, body, mind, and soul” (p. 120).

Using narrative research approaches, Magro (2008) interviewed newcomers and refugee youth and adults in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Teachers, counsellors, and educational administrators working with newcomers were also interviewed. One young man (now in his early thirties) had been a teenager when the civil war broke out in Sierra Leone, Africa. This student (David) found many similarities between his own personal observations and the film Blood Diamonds by Greg Campbell (2004), a true account of diamond smuggling and how the rebel wars have devastated Sierra Leone and its people. David wrote:

When the war in Sierra Leone was at its peak in 1998, I was a teenager working in the diamond mines. I was captured by the rebels and had to work for them so it was a miracle that I escaped on the third night. I could have been recaptured and killed. I walked in the forest for many miles until I found safety. When I lived in Sierra Leone, I saw horrible things. There was no respect for humanity. Since I have been in Canada, I have been lonely. However, there is freedom and human rights. I saw the respect for humanity in Canada and this has motivated me to help my people back home. I am particularly interested in making a documentary about the innocent amputees in Sierra Leone. They are victims of war and their lives changed in a second. They all deserve to have help and have their dignity restored. I would like to help build a health facility for the disabled—similar to the ones I have seen in Canada. In the west, a diamond is a symbol of wealth and prestige, but in my home country, in Sierra Leone, it is a symbol of misery(Magro, 2008, p. 27)

Narratives like the one above reinforce the value of teachers being able to understand the social and cultural backgrounds of their students more deeply. Weber (2006) emphasizes that “the very act of writing invites reflection by both students and teachers, which can take place in journals, letters, poems, speeches, formal essays, or more informal personal essays. Whatever the form used, students should see writing as a means of thinking through changes and dilemmas that they and others face” (p. 26). He further notes that the larger question concerning the relevance of such personal writing lies in understanding and appreciating how they may have changed or improved, and “an understanding of the larger implications of certain events or actions” (p. 27). All of our students had powerful narratives to share. In reading biographical accounts and in encouraging students to write autobiographies and personal reflections, English teachers can honour and validate their students’ prior experiences.

Qureshi (2006) asserts the importance of students being able to read literature that challenges their assumptions, values, and lifestyles. She developed an English course called “Global Voices”, aimed at breaking down cultural stereotypes and improving cultural understanding and critical insight. Qureshi (2006) writes that “in the post 9/11 world, it is no longer sufficient for students to read literature that affirms their circumstances, values, or lifestyles…students must actively engage in looking through many and varied windows so they can make informed choices as global citizens” (p. 35). In reading texts from a range of cultures, students become more aware of cultural misconceptions and social justice issues. Three key questions can be explored by students as they read texts from around the world:

What is familiar or unfamiliar to you about these books?

What misconceptions do you have about any of the books based on their country of origin, title, or the author’s name?

What connections can you make between these books and your own life? (pp. 3-4).

By fostering empathy and perspective-taking into the lessons, Qureshi (2006) states that “by the end of the year, students have explored the spiritual, physical, and emotional implications of humane and inhumane acts across cultures. Only then can they successfully turn the mirror on themselves to evaluate humanity and arrive at a set of universally valued human rights” (p. 37). Self-directed reading is integrated with group discussions and presentations. The texts must be written by a writer native to that culture and each text should explore contemporary issues revolving around politics, landscape, family/ relationships, economics, traditions, religion, and social constraints. Themes connected to suffering and courage as part of the human condition were used to explore African literature. Texts included Under African Skies: Modern African stories (edited by Charles R. Larson), Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, Chinua Achebe’s Things fall Apart and the film Hotel Rwanda. Themes such as the crisis and awakening, betrayal, human dignity, and justice are addressed in texts like these. Universal themes in literature can cross cultural boundaries and give students unique opportunities to explore a broad range of social justice themes. In addition, students who read texts that are representative of cultural contexts they are familiar with may feel a greater sense of inclusion and validation.

Integrating photography, art, sculpture, and collage to reflect scenes, characters, conflict, and mood can add an additional dimension to the study of these compelling literary and non-fiction works.

Encouraging Empathy to Bridge Cultural Divides: The Power of Storytelling

The art of storytelling can be a creative way to help engage literacy learning while also building valuable emotional intelligence skills such as empathy and intercultural understanding. Canadian teacher Marc Kuly (2013) used Ishmael Beah’s book A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Child Soldier to embark on a storytelling project. Kuly’s intent was to help his students develop empathy and intercultural intelligence; in sharing their personal narratives, cultural misconceptions might be broken down. Writing their own stories and presenting them in front of an audience was also a way for Kuly’s students to develop self- confidence and personal empowerment.

Working in the inner city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Kuly taught students from diverse cultural backgrounds: First Nations and Metis, newcomers from war ravaged countries like Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and those students coming from Euro-Canadian backgrounds. Many of these learners experienced hardship in life: the death of a parent and/or siblings; an alcoholic parent; conflicts with insecurity and depression; and financial hardship. The storytelling project that Kuly started evolved into an award-winning documentary film, The Storytelling Class. Each of Kuly’s 18 senior high students describe their own life story as a way of finding a “common bond” with their classmates from very different cultural backgrounds. Students shared personal hopes, fears, dreams, and disappointments. In reading about Beah’s story of abduction and his years of being forced to work as a child soldier in Sierra Leone, the students began to reframe their own tragedies and struggle. Kuly’s own ability to reach his students from an emotional angle, provides an insight into the important role that teachers have as advocates and change agents in the classroom. Approaches to teaching literacy go beyond traditional texts and testing formats to transform students’ perceptions of themselves, of others, and of the world.

Marika, a newcomer and refugee from Liberia, explains how the power of sharing stories led her to change her perspectives of “white kids”:

I always thought working with white kids was something really difficult. I had this feeling that they would not understand what [the African kids] were talking about. But when I heard their stories, well now I have a different view of white kids. It’s not like because you are white that you have everything and that you have no pain in your life—you do have pain and sorrow; it’s all the same (Kuly, 2013,p.42.).

Stories of trauma can be used in educational settings to expose power relations and constructions of identity. Storytelling can be connected to the way power is constructed, contested, and shared “because of its potential to create vulnerability for tellers and audiences alike” (p. 35). Used therapeutically, storytelling can be a first step in an individual’s gaining a sense of agency in their life and creating or constructing a healthier self-concept. Kuly (2013) felt that regardless of the occupation or profession his students choose in life, he is convinced that their educational experiences have empowered them. Developing their own voice within a public context that values and affirms their narrative can foster leadership skills and self-efficacy. “When we hear another person’s stories, it allows us to walk in their shoes” and develop empathy. (Senehi, 2013, p. 124).

Senehi (2013) explains that storytelling can be a powerful strategy when used in positive ways. However, the telling of one’s story must be done in a context of respect and safety. While language, words, and narrative have the potential to empower, they can also oppress when ethical boundaries are violated. Senehi (2013) explains that storytelling can be harmful or destructive in three key instances: when dominant discourses exclude groups of people who have been marginalized; when stories are misused to spread hatred, rumour, and discrimination; and when stories misrepresent or distort the truth (p. 123). Used in a positive and transformative spirit, storytelling can be healing; it can create opportunities for dialogue and insight (p. 123). Students can also complement their stories and personal memoirs with artistic creations.

Gender Matters: Encouraging Social Justice Awareness with Memoirs

A Bed of Red Flowers by Nelofar Pazira, Slave by Mende Nazer, and Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns give a startling insight into the experiences of young girls and women caught in the violence of war. Nelofar Pazira’s, A Bed of Red Flowers, (2005) riveting personal account of life in Afghanistan before and after the repressive Taliban rule portrays how occupation, political corruption, and human rights violations have eroded hope and dignity. While she made her escape to Canada and now lives as a journalist and film maker (Khandahar and Return to Khandahar) in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Pazira hopes to increase awareness of the desperate and dire fate of girls and women in Afghanistan, a troubled country that has known little peace. Returning to Afghanistan in search of her friend Dyana, Pazira recounts the historical, political, and cultural changes that shaped Afghanistan and its people today. In her memoir, she writes that Kandahar was once

… a place of harmony and culture, of wealth and beautiful gardens and music and poetry. The city was famous for its pomegranates. The blossoms of pink and red roses, which Kandaharis still cherish around their windowsills, are a memory of this beauty … Now, Kandahar is now a city of extremes, a place of men and guns, expensive cars and starving children. It is oven-hot, a dry blowtorch heat that sucks colour out of the landscape. Even in post-Taliban Kandahar, there are few signs of women. Those who venture out are covered from head to toe, whether in burqas or in long, Arab-style black coats and head scarves that also cover their faces, except for their eyes.” (p. 335)

Similarly, Khaled Hosseini’s (2004) A Thousand Splendid Suns portrays the way brutal and oppressive laws against women in Afghanistan destroy individual dreams, families, and lives. Through the powerful characters of Mariam and Leila, issues related to human rights violations can be explored at a deeper level. Set in Sudan, Mende Nazer’s (2003) Slave is a true account of a young Nuba girl abducted and forced to live as a slave in the home of a wealthy Muslim family north of Khartoum. Nazer’s rich oral tradition enabled her to remember vivid details from her childhood and her teen years. Her life in Karko was “simple and peaceful” until the Mujahedin raided her village. “One night when I was 12 or 13, we heard a noise outside. The village was on fire. We didn’t know what we had to do…We had to run, we had to survive.” (p.102). Separated from her family, she was raped and sold as a slave. Nazer’s autobiographical account reveals a young woman of tremendous courage and resourcefulness. She drew upon the memories of her loving family as a way to cope with years of mental and physical abuse she endured. Toward the end, she writes that “the nightmare of my years in slavery didn’t end as soon as I escaped. It was just the nature of my suffering that changed. After escaping, I wasn’t worried so much for my own future or security anymore. I was far more worried for the safety of my family back in Sudan, and the safety of those who had helped rescue me and those who enabled me to be free (p. 318).

Since the publication of her story, Mende Nazer has spoken at universities on issues of human rights abuses. She states “Now I feel I’m free because I am doing things I never used to do before…For me the reason for talking out is to help make another slave free…not just a slave from Sudan, but from anywhere in the world. By talking out, people will be more aware and more able to help people become free.” Empathy, intercultural understanding, and a respect for others’ experiences are more likely to occur when learners are given an opportunity to identify with the struggles that a character may be going through, regardless of colour, geographical distance, and ethnic background.

Wangari Maathai’s (2006) Unbowed is an inspirational and beautifully written memoir of the first African woman and first environmentalist to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In Unbowed, Maathai recounts her youth and adulthood as she struggled to attain an education amid a social climate of sexism and tribalism. Her work as a professor and activist in environmental and women’s rights earned her the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004, but this achievement was not without a price. Maathai recounts the political persecution she faced, her failed marriage, and the growing social and emotional isolation she experienced as a result of her outspoken criticism of the political corruption around her. In an effort to restore the indigenous forests, Maathai started the “Green Belt Movement” which led to the planting of over thirty million trees across Kenya since 1977. She writes that “the Green Belt movement has also inspired greater awareness of the need to protect other forest ecosystems in Africa that are under threat, especially the Congo Basin Forest. The Congo and Amazon forest ecosystems are two of the most important ‘lungs’ of planet Earth” (p. 274). Through her memoir, students can gain an insight into Kenyan life and tradition. Students reading this text can integrate their literary analysis with research on the geography and political climate of Kenya, both past and present. They could also integrate this text with research on a current topic like environmental sustainability. Photographs and landscape art can be used to complement the Maathai’s memoir. A comparison of other biographies and autobiographies can also be explored. Students can also write their own autobiographies as a way to place their experiences in context within a particular culture and social milieu.

Maathai’s motivation to start the Green Belt Movement emerges, in part, from her affinity toward nature, and her sense of helplessness and sadness as animal and bird species lost their habitat due to the deforestation that occurred to make room for emerging industries in Kenya. She recalls her love for the wild animals populating the forests of her youth in vivid prose: “I was always attentive to nature. Ihithe borders the Aberdare forest and our area had many wooded plots. As a result wildlife was abundant. I knew there were elephants, antelopes, monkeys, and leopards in the forests. Even though I never saw these animals, my mother encouraged me not to be afraid of them” (p. 43). Discussion questions for this memoir might include some of the following:

- What do you know about Kenya?

- Where is it located?

- Write a brief report on aspects of Kenyan society, that include the political structure, the role of men and women, the educational systems, the cultural traditions, the history, the geography, and so on.

- Create a collage of photographs and art that reflects the people, landscape, animals, and architecture of Kenya.

Students could begin with a KWL chart. Write their responses in the first section of a three-column chart, identified K for “Know.” Ask them what they would “Want” (W) to know and then the third column could be an ongoing recording of what they have “Learned” ( L) about Kenya from their reading.

- If you could interview Wangari Maathai, what would you ask her? Write ten to twenty questions and discuss them with a partner.

- Women are considered symbols of many different things in most cultures. Maathai speaks about women being “carriers and promoters of culture.” Trace this idea in the memoir. Where does this idea cause conflict for Maathai and what does she do in response?

- Maathai wrote: “A great river always begins somewhere” (p. 119). She ended up becoming an environmentalist, a women’s rights activist, a politician, and a dissident. Choose one of these roles and trace the origins and development of Maathai’s roles by creating a timeline.

- Choose another environmental movement or organization, either in Canada or elsewhere, and write an essay on it comparing and contrasting it to the Green Belt Movement. (Questions from the Random House Teacher’s Guide for Unbowed are located in: www.randomhouse. com/academic).

A number of narratives set in different cultural contexts can introduce students to social injustice, the plight of child soldiers, the refugee experience, and the difficulties involved in navigating unfamiliar cultures and languages.

Xerri and Xerri Agius (2015) used poetry as a way for their students to build empathy and intercultural awareness. In their research, they specifically used poetry to help their students understand the plight of refugees fleeing the Middle East and finding a safe haven in the Mediterranean islands like Malta. In sharing poetry written by refugees fleeing war-torn countries like Eritrea, Somalia, Syria, Libya, and Iraq, their Maltese college- level students became more sensitive and understanding about the refugee experience. Cross-cultural understanding, and abstract issues that include racial, economic, and gender inequities can emerge in ways that enabled their students in Malta to understand the “mindset of an individual caught between two cultures, trying to find a sense of identity in alien surroundings” (Chavis, 2013 cited in Xerri and Xerri Agius, pp. 71-72). They also wanted to help their students break down cultural misconceptions and fears of being “invaded” by refugees seeking a safe haven on their tiny island. Racism, tension and a lack of security, overpopulation, job availability, economic burden, and the devaluing of citizenship were themes that emerged from the students who wrote poems about their fears of refugees fleeing to Malta. These researchers then shared the poems written by refugees that focused on the hardships that forced them to leave their home countries of Somalia and Eritrea. Xerri and Xerri Agius found that after exploring the poems written by the refugees seeking a safe haven in Malta, and by the students in Malta, a greater empathic understanding of the experiences of immigrants could be learned. Through this poetry project, the students transformed their “preconceptions and [were able to] advocate a more sympathetic attitude toward immigrants and their plight…we hope that this lesson served to nudge them into a long-term embrace of the emerging multiculturalism of contemporary Maltese society” (p. 75). The research by Xerri and Xerri Agius point to a deeper way that the exploration of literary texts can reflect emotions, values, and beliefs. Vaughn (2015) suggests that rather than asking students to explain the “meaning” of a particular poem, it might be more appropriate to explore where a particular poem is located from a psychological, spiritual, and physical stance:

Ask what part of us the poem might be speaking to or what emotions the poem might be trying to evoke. Is the poem speaking to our own dream life? If, so, it will use dream-language and dream-images, which are quite different from waking language and waking images. Is the poem speaking to our philosophical wanderings/wonderings? Is it speaking to our vulnerability, to our rawness, to our spiritual pain, or to our shadow self? Whatever the place or state may be, the language, imagery, method, and experience of the poem may differ greatly. (Vaughn, 2015, p. 16)

Visual art, photography, sculpture, and other artistic media can be explored in ways that complement any of the texts described above.

Creative and Divergent Thinking

Teaching English provides many opportunities for students to engage in creative thinking and divergent thinking. In their literacy research, Rish and Caton (2011) describe an English class where students read fantasy and science fiction while participating in a project called “Building Worlds”, a writing project where students “create a fantasy world to learn about the choices fantasy authors make when telling a story” (p. 21). Students read excerpts from Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to examine the way language, culture, and character are created in a fantasy setting. Students were engaged in creating maps and drawings, historical narratives, and descriptions of fantasy characters, creatures, and deities. Texts were being reconfigured in a new way that also challenged students to work together collaboratively. Literacy, in this context, is being defined as a complex socio-cultural process that involves dialogue, negotiation, and compromise. Contemporary versions of classical films can be further examined by comparing the film with the novel. In recent years, adaptations of familiar classics like Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Orwell’s 1984, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, and J. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit are introduced to new audiences who may be unfamiliar with the original text. No doubt for some, the film may be a catalyst to reading the original work. Innovative ways of exploring setting and point of view can encourage literacy motivation.

Smith and Wilhelm (2010) draw upon the psychological theories of Carl Jung, Uri Bronfenbrenner and Lev Vygotsky, to highlight the complex ways that setting can be explored through an analysis of different contexts: psychological and social, physical or geographical location, and the historical time period. These dimensions of setting interact with one another to influence the trajectory of characters’ motives and actions. Smith and Wilhelm (2010) write that “the social/psychological dimensions of setting are a function of the systems of relationships among the characters” (pp. 70-71); the story’s geographical dimension addresses the “country, city, neighborhood, and street; its features as far as natural artifacts, style, architecture, floor plan, rooms, and furniture. The physical setting is how a story is located in a specific space or spaces” (p. 70). The temporal setting refers to the period or era of the story and its duration in time (distant past, recent past, present, future). The brevity of stories can further shape the characters, conflict, and basic plot structure (e.g., The Awakening by Kate Chopin and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitzyn.). By integrating psychological theory with literary analysis, students can make deeper connections. Smith and Wilhelm (2010) refer to CHAT ( Cultural- Historical Activity Theory) to analyze the way individual behaviours are embedded within social and historical contexts:

CHAT is a psychological framework that derives from Vygotsky’s socio-cultural work in psychology. His followers Leont’ev and Rubinstein founded this theoretical framework to explore human activities as complex, socially situated phenomena in ways that went further than the then-current behavioristic (stimulus-response) notions of human behavior. (Interestingly, many current educational practices such as grading, information-transmission instructional practices, and standardized testing hark back to behavioristic notions of teaching and learning that are considered outmoded in their psychological conceptions of teaching, learning, and understanding). Activity theory is useful to a consideration of setting because it highlights that Any human activity – whether internal or external—is in fact allowed, encouraged, shaped, and constrained by the particular social situation in which it occurs. Activity theorists argue that human behavior can be highly creative and non-predictable, but it is always situated and must be understood in situations. (pp. 65-66)

Smith and Wilhelm (2010) provide templates and activity charts such as “Making Predictions” and “Evaluating Changes in Setting” that integrate drama, music, role plays, photographs, and the analysis of well known paintings such as Van Gogh’s “Bedroom at Arles.” Indeed, the use of artistic creating can be a fascinating way to examine the way that setting captures tone, atmosphere, and theme. Works of art can illuminate particular themes that emerge from studying texts. Literacy teachers can build on a rich repertoire of resources to encourage literacy learning among diverse students. Applying personality and learning style inventories are further ways to enrich students’ understandings of the complexity of character, conflict, and context.

Irvin (2012) details the way she taught Jeannette Walls’s memoir The Glass Castle to encourage the development of emotional intelligence. Irvin teaches in a high-poverty area where many of her students face adversity in the form of chronic self-doubt, depression, poverty, exposure to violence, parental alcoholism, and the lack of a stable and safe home life. As a teacher of young adults, she integrated emotional and social intelligence into the curriculum by challenging her students to analyze the characters’ motives, actions, and consequences. She carefully integrated themes from the novel with her students’ lives. Students began to explore the role of parents and parenting styles and their impact on a child’s personality. Walls’s memoir portrays the struggle of growing up poor and of having to cope with a transient lifestyle, financial destitution, an emotionally unstable mother and father who suffered from alcoholism. Despite the hardship she experiences, “Walls continually strives for improvement and she eventually leaves home at the age of 16 to begin her own, more normal life” (p. 58). Walls’s own writing becomes a source of therapy; while her father never “built the glass castle” she herself, with determination and perseverance…“puts the demons in her own life to rest by writing her memoir” (p.58). Walls’s memoir becomes an anchor for the students to explore their own lives by asking what they would do if they were in a similar situation? What dreams do they have for their future and how would they begin to realize their dreams? What barriers stand in the way of their dreams and how can these barriers be reduced or removed? Some of Irvin’s students decided to research childhood poverty and to learn more about the poverty-stricken coal-mining town of West Virginia. Her research led her to a social action project that raised enough money to distribute 1,000 books to her own community. Writing can be purposeful and even transformative. Teachers have the potential to develop a literature and non-fiction course based on psychological and social topics that involve challenges in young adulthood, the world of work, travel, developing a strong identity and building positive relationships, career choice, family systems, relationships, parenthood, coping with stress, and decision making (Magro, 2009). A careful study of the use of literature, non-fiction, drama, and writing can be reframed to examine powerful psychological and social themes. A study of William Golding’s classic Lord of the Flies or Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus can be an exploration of bullying and group conformity, class structures, abuse of power, and the struggle to establish one’s voice. Mack (2012) asserts:

Emotional literacy has an important place in the English curriculum because emotions cannot be separated from reading, writing, and thinking critically with language. Language gives us the means to make conscious decisions about how we act, speak, think, and feel. If at first we feel hurt or humiliated, thinking through the experience can actually change how we feel about it… Personal tragedy can be rewritten into a lesson in courage that we credit with strengthening our will to survive… ( Mack, 2012, p. 18).

Empathy and an appreciation of diverse experiences are more likely to occur when learners are given opportunities to identify with the struggles that a character may be going through regardless of their ethnic and racial background, culture, and geographic distance.

Art and Poetry as Catalysts for Imaginative and Creative Thinking

In his book Nurturing the Peacemakers in Our Students, Weber (2006) emphasizes that emotional intelligence skills like empathy and self-awareness, can be taught through poetry and art. Weber defines ekphrastic poetry as the poetry of empathy, requiring the viewer/poet to “enter into” the spirit and feeling of the subject through a variety of poetic stances: describing, noting, reflecting, or addressing” (p. 33). He asks his students to find a photograph, piece of art, print, or sculpture that profoundly inspires them. Weber gives his students time to find their artistic form in libraries, photography books, newspapers, and travels to art galleries, museums, and so on. At the end of the assignment, the students present their image/work and their poetic response to the class. “I give my students several weeks to search for a work that truly inspires and engages them ‘to enter into the spirit.’ The results of this researching and reflecting time prove to be highly productive as students’ ekphrastic responses help them to enter, define, and develop a curriculum of peace” (p. 45). To introduce the topic of war and peace, Weber first teaches a lesson on empathy by using several texts about the Holocaust. Robert O. Fisch’s memoir “Light from the Yellow Star: A Lesson of Love from the Holocaust”, in addition to poems and famous photographs capturing the tragedy of the Holocaust; these provide the cornerstone of Weber’s teaching about peace and social justice issues. Weber (2006) emphasizes the importance of teachers being able to explain and clarify the historical and cultural context of different texts. Throughout this book and the related art-text resource guides, specific examples of poetry connected to visual art are featured. Learners can develop their own compilation of favourite poems and art.

Moorman (2006) suggests that poetry that is connected to art can be a creative way to help students become more deeply aware of the similarities between the visual and the verbal arts. Emory University professor Harry Rusche developed a web site The Poet Speaks of Art that provides forty-five examples of ekphrastic poetry along with their corresponding paintings. Other resources that Moorman uses include Heart to Heart: New Poems Inspired by Twentieth Century American Art, edited by Jan Greenberg, and Belinda Rochelle’s Words with Wings: A Treasury of African –American Poetry and Art; these can be used to inspire creative writing and new forms of art. Specific linking the visual art to the poem can be developed. The poem provides another modality to think more transformatively about themes centering around travel and place, youth and age, death and grief, spirit and faith, inspiration and joy, family life, love, war, nature, and so on. Some examples of pictures and poetry that Moorman presents include: Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh and Anne Sexton’s poem “The Starry Night”; The Corn Harvest by William Carlos Williams and “The Harvesters” by Pieter Bruegel; “Before the Mirror” by John Updike and Girl Before the Mirror by Pablo Picasso. Students can also create their own free verse poem based on a painting they have chosen. Painters and poets attend to details and images; writing and the visual arts are ways of engaging with the world more creatively. Comparisons can be made between the poet’s themes and the artist’s purpose, or the poet’s point of view and the artist’s perspective. Figurative language like simile, imagery, and symbolism can be compared to the artist’s use of colour, brushstroke, and artistic medium and style. Visiting local art galleries and museums and looking on line to find “virtual tours” of art galleries and museums are ways that students can be inspired to write and to visualize. Descriptive essays, photographs of images that students found most compelling, art reviews, letters, interior monologues, or short narratives in response to art that the students choose can further extend the students’ writing. Students can select, analyze, and interpret art work and photography, then write a poem or descriptive narrative that corresponds to a particular photograph or painting based on categories such as “stories”, “voices”, “impressions,” or “expressions” (Moorman, 2006).

A visit to an art gallery or a virtual visit can be a catalyst for creative and critical thinking and writing. Viewing paintings from divergent perspectives can help students understand the complex and nuanced way that artists express themselves. In C. Krieghoff’s “Bilking the Toll” (1860) students can be asked to write about the variety of characters (human and animal); the painting is dynamic and could be a catalyst to writing a mystery or adventure story.

Courtesy: By Cornelius Krieghoff – Self-photographed by Mzajac of original painting., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58890332

At another level, “Bilking the Toll” may reveal a tension between the English colonial government that established a toll booth system in upper Canada in the 1800s and the local French population that had to pay the toll booth tax.

A Closer look from a psychological, social, cultural, and historical lens of Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675).

Courtesy: By Johannes Vermeer – The National Gallery of Art, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12378177

The paintings of Jan Vermeer can be used to encourage creative writing and a discussion of motivation. Based on her clothes and the setting, what can viewers deduce about her social class and standing? In “A Lady Writing” students could examine the body language and expression of the young woman. What might this woman be writing about? Could it be a love letter? Based on her expression, what emotions is she feeling? Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid” and “The Lady Writing” can be explored from a psychological, social, cultural, and historical stance. How different were the lives of the wealthy compared to those in the working classes, including individuals working in domestic contexts. Students can look more closely at the setting and the woman’s gesture of pouring the milk. Vermeer’s paintings often depict scenes from everyday life. What might the woman be thinking? Further research into the illusionist and photographic likeness of Vermeer’s art (see “View of Delft” by Johannes Vermeer). (for more information about Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid please open the essay by Giordana Goretti (2023) here.

Courtesy: By Johannes Vermeer – 9AHrwZ3Av6Zhjg — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13408941

Courtesy: By Johannes Vermeer – www.mauritshuis.nl : Home : Info : : Image, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50398