Chapter 9: A Closer Look at Vincent van Gogh Through his Letters and Art

Calm even in catastrophe(Vincent van Gogh, 1888).

Looking at the stars always makes me dream (Vincent van Gogh 1888).

“Well, the truth is, we can only make our pictures speak….Well, my own work, I am risking my life for it and my reason has half foundered because of it—that’s all right–..” – Vincent Van Gogh, letter to his brother Theo, Arles, Auvers-sur-Oise, July 23, 1890, in Auden (Ed), Letters, p.398).

Exploring Vincent Van Gogh’s Art and Letters

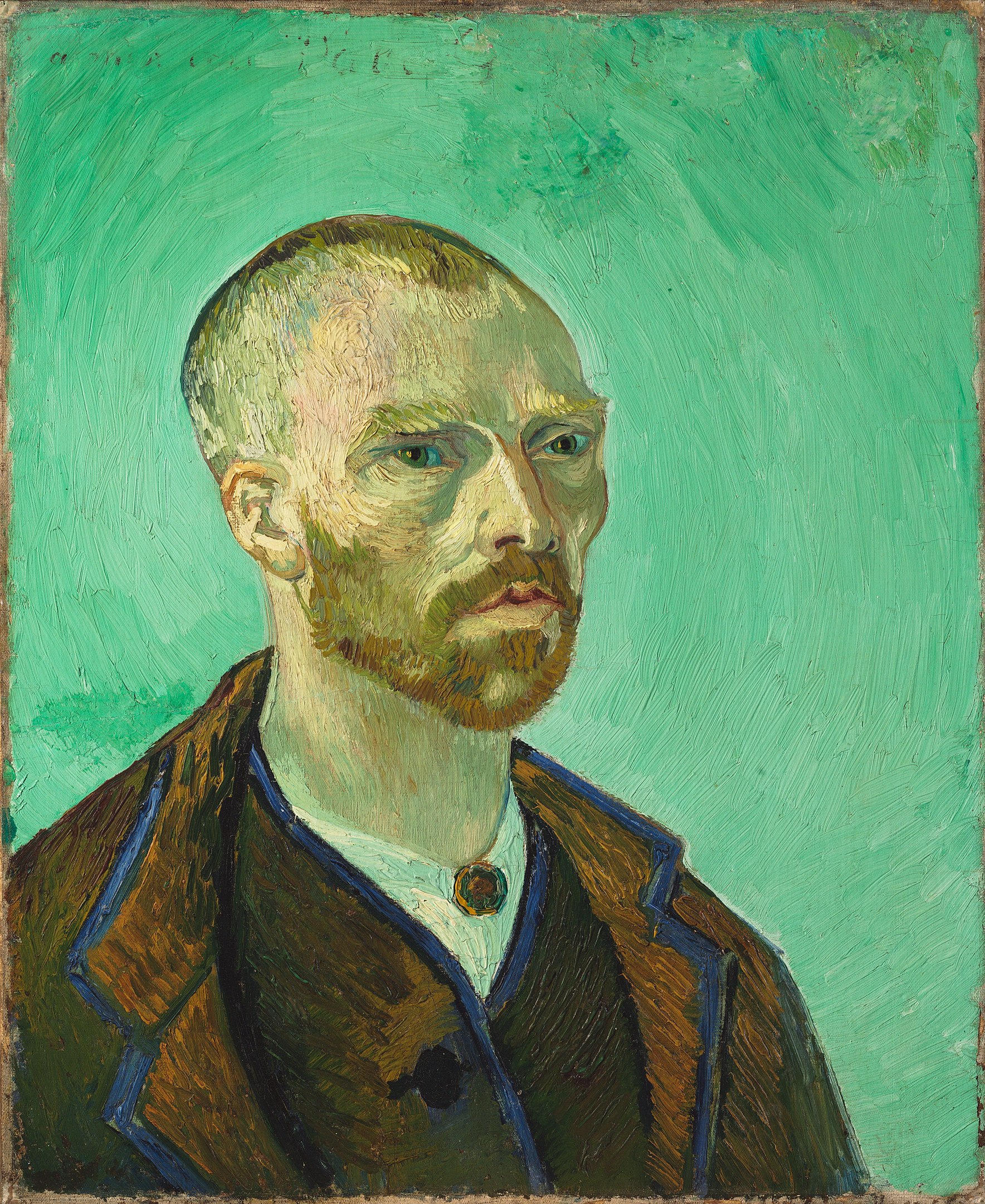

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. Web Museum, (file)2. Google Art Project, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9857

The art works of the post-impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) can be seen as visionary and transformative. Each painting seems to reflect a brilliant sensitivity that van Gogh had to his natural surroundings and the mysteries of the cosmos. The bold colours and brush strokes that van Gogh used reflect intense emotional states. van Gogh’s letters include many poetic verses and symbols. In his letters to his brother Theo, Vincent reveals his insights and reflections on nature, people, and landscapes. He provides details on his choices of subjects to paint, the colours his uses, and his overall approach to paintings. van Gogh’s letters further reveal detailed commentary on contemporaries like Paul Gauguin and artists like Francois Millet, Raphael, Eugene Delacroix, and Rembrandt. His close observation and attention to colour, line, landscape, and people, are evident in his work. Van Gogh was aware of the precarious and fickle nature of the art dealing world; his letters to Theo reveal his deep introspection about the ephemeral nature of life, the meaning of life, and the tension between being true to oneself and surviving in a world of rejection and judgement. His appreciation and love for his brother Theo feature in all his correspondences to Theo.

During the short time van Gogh stayed in Arles until his death (1889-90), he produced an astonishing 187 paintings. Despite the brilliance of his artistic talents and despite his uncanny sensitivity and awareness of the human condition and nature around him, Vincent could not break free of the doubt, malaise, and deep depression that ultimately led to his untimely death. In a decade, van Gogh created over 2,000 art works. His influence on art continues to this day. As you read his letter excerpts and then view selected paintings, what impression do you have of Vincent van Gogh and his perspectives about life, love, art, and nature? You can explore more of van Gogh’s works through a virtual tour of the van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The letter excerpts featured in this chapter are from W.H. Auden’s (1963) van Gogh: A self-portrait: Letters revealing his life as a painter. E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc.

Alienation and Depression: Excerpts from Letters to Theo

Vincent van Gogh struggled with loneliness, melancholy, and insecurities. His resilience, courage work ethic, and passion to see and document the beauty of life is reflected throughout his art: “one must bear hardships in order to ripen.” (van Gogh, in Auden, 1963, p. 136). van Gogh’s words reveal his keen insight and almost prophetic sense of his destiny. van Gogh is keenly awareness of the importance of community yet recognizes that while he is an observer, he feels like an outsider, not really connected as a full participant who is accepted, valued, and understood:

I feel older only when I think that most people who know me consider me a failure, and that it might really be so if some things do not change for the better and when I think it might be so. I feel it so intensely that it quite depresses me and makes me as downhearted as if it were really so. In a calmer and more normal mood I am sometimes glad that thirty years have passed, and not without teaching me something for the future, and I feel strength and energy for the next thirty years, if I live that long.”

And in my imagination, I see years of serious work ahead of me, and happier than the first thirty.

How I will be in reality doesn’t depend only on myself, the world and circumstances must also contribute to it.

What concerns me and what I am responsible for is making the most of my circumstances and trying my best to make progress…

Well, many things in life really begin at the age of thirty, and certainly all is not over then. But one doesn’t expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give; rather one begins to see more and ore clearly that life is only a kind of sowing time, ad the harvest is not here. (van Gogh, Letter to Theo, 1883, in Auden (Ed.), p. 136).

In a letter to his beloved brother Theo, Vincent writes about the “élan of his bony carcass” in a self-portrait dedicated to fellow-painter Paul Gauguin:

These days I have an extraordinary feverish energy; at the moment I am struggling with a landscape that has a blue sky over an immense vine, green, purple, yellow, with black and orange branches. Little figures of ladies with red sunshades and of vintagers with their carts enliven it even more. In the foreground, gray sand….

I have a portrait of myself, all ash-colored. The ashen-gray color that is the result of mixing malachite green with an orange hue, on pale malachite ground, all in all in harmony with the reddish-brown clothes. But as I also exaggerate my personality, I have in the first place aimed at the character of a simple bonze* worshipping the Eternal Buddha. It has cost me a lot of trouble, yet I shall have to do it all over again if I want to succeed in expression what I mean…” (p.336).

*A bonze is a Japanese or Chinese monk. It is important to note that Vincent van Gogh wrote many of his letters in French; as a result of the translation, there may be variations in meaning of the interpretation of words and phrases.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=93338600

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – BgFGcS3ucZqeRA at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22621957

The Interaction between humans and nature

“Look here, there is another question that comes to mind. Who are the human beings that actually live among the olive, the orange, the lemon orchards?

The peasant there is different from the inhabitant of Millet’s wide wheat fields. But Millet has reawakened our thoughts so that we can see the dweller in nature. But until now no one has painted the real Southern Frenchman for us. But when Chavannes or someone else shows us that human being, we shall be reminded of those words, ancient but with a blissfully new significance, Blessed are the poor in spirit, blessed are the pure of heart, words that have such a wide purport that we, educated in the old, confused and battered cities of the North, are compelled to stop at a great distance from the threshold of those dwelling…” (van Gogh in Auden, Letters, p.197).

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. vggallery.com2. Bridgeman Art Library: Object 593575, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2432746

Courtesy: The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 1998, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437998” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Painting the Olive Trees:

“The effect of daylight, of the sky, makes it possible to extract an infinity of subjects from the olive tree. Now, I on my part sought contrasting effects in the foliage, changing with the hues of the sky. At times the whole is a pure all-pervading blue, namely when the tree bears its pale flowers, and big blue flies, emerald rose beetles and cicadas in great numbers are hovering around it. Then, as with the bronzed leaves are getting riper in tone, the sky is brilliant and radiant with green and orange, or more often even, in autumn, when the leaves acquires something of the violet tinges of the ripe fig, the violet effect will manifest itself vividly through the contrasts, with the large sun taking on a white tint within a halo of clear and pale citron yellow. At times, after a shower, I have also seen the whole sky colored pink and bright orange, which gave an exquisite value and coloring to the silvery gray green. And in the midst of that there were women, likewise pink, gathering fruit.” – Vincent van Gogh, 1890, Auden, Letters, p. 396.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes

“This is one of five pictures of olive orchards that van Gogh made in November 1889. Painted directly from nature but animated by Seurat-like stippling and stylized passages of broken color, these works responded to recent compositions by Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard. “What I’ve done is a rather harsh and coarse realism beside their abstractions,” Van Gogh observed, “but it will nevertheless impart a rustic note, and will smell of the soil.” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.2. Unknown source3. Yale University Art Gallery, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151915

Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo (excerpt, the Hague, 1882):

“One is afraid of making friends, one is afraid of moving; like one of the old lepers, one would like to call from afar to the people: ‘Don’t come too near me, for [association] with me brings you sorrow and loss. With all that huge burden of care on one’s heart, one must set to work with a calm everyday face, without moving a muscle , live one’s ordinary life, get along with the models, with the man who comes for the rent—in fact, with everybody. With a cool head, one must keep one hand on the helm in order to continue the work, and with the other hand try not to harm others.

And then storms rise, things one has not foreseen; one doesn’t know what to do, and one has a feeling that he may strike a rock at any moment..” (van Gogh, 1882 in Auden (Ed) (1963), van Gogh, Letters, p. 126).

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – kQEugEsNjGDZfw at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21855885

“It is a painter’s duty to make an idea into his work” – Vincent van Gogh, 1885.

van Gogh’s empathy for others’ suffering is evident in his paintings like “The Potato Eaters.” In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh explains: “I have tried to emphasize that those people, eating their potatoes in the lamplight, have dug the earth with those very hands they put in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labor, and how they have honestly earned their food” (van Gogh, 1885, in Auden (Ed), p. 137). van Gogh saw “something noble, something great” about individuals’ motivation to survive amid adversity. In his observations, van Gogh saw a larger spiritual panorama that connected individuals to the land and the larger cosmos. van Gogh projects his own sense of isolation, loneliness, and solitude onto his landscapes and portraits. He hoped that his paintings might teach and enlighten individuals unfamiliar with the harshness of peasant life.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – Zoom folder : Tiles folder (see “Notes” for assembly details), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=334091

Note about the Potato Eaters by Vincent van Gogh (van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

“van Gogh saw the Potato Eaters as a showpiece, for which he deliberately chose a difficult composition to prove he was on his way to becoming a good figure painter. The painting had to depict the harsh reality of country life, so he gave the peasants coarse faces and bony, working hands. He wanted to show in this way that they ‘have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish … that they have thus honestly earned their food’.

[van Gogh] painted the five figures in earth colours – ‘something like the colour of a really dusty potato, unpeeled of course’. The message of the painting was more important to van Gogh than correct anatomy or technical perfection. He was very pleased with the result: yet his painting drew considerable criticism because its colours were so dark and the figures full of mistakes. Nowadays, The Potato Eaters is one of van Gogh’s most famous works.” (van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

van Gogh’s Expression of Emotion in Art

“I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green. The room is blood red and dark yellow with a green billiard table in the middle; there are four citron-yellow lamps with a glow of orange and green. Everywhere there is a clash and contrast of the most disparate reds and greens in the figures of little sleeping hooligans, in the empty, dreary room, in violet and blue. The blood-red and the yellow-green of the billiard table, for instance, contrast with the soft tender Louis XV green of the counter, on which there is a pink nosegay. The white coat of the landlord, awake in a corner of that furnace, turns citron-yellow or pale luminous green” ( van Gogh, 1888, in Auden (Ed.), Letters, p.320).

Additional Resources

Connecting Texts to Explore:

“A Clean Well- Lighted Place” by Ernest Hemingway.

“I am a rock” by Paul Simon

“Eleanor Rigby” by Paul McCartney and John Lennon.

“Starry starry night” (song by Don McClean).

Song version (You Tube) of Don McClean singing “Starry Night”

“The Starry Night” by Anne Sexton.

“Mysteries remain, and sorrow or melancholy, but that eternal negative is balanced by the positive work which is thus achieved after all.” -Vincent Van Gogh ( Letter to Theo, 1883, in Auden, (Ed.) 1963, p. 156)

Dzouza, L. (2023). 11 Quotes from Vincent van Gogh that will inspire your artistic journey.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – uQE3XORhSK37Dw at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21856227

Stars and Celestial Locomotion

“Painters—to take them alone—dead and buried speak to the next generation or to several succeeding generations through their work. Is that all, or is there more to come? Perhaps death is not the hardest thing in a painter’s life.

For my own part, I declare I know nothing whatever about it, but looking at the stars always makes me dream over the black dots representing towns and villages on a map. Why, I ask myself, shouldn’t the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? Just as we take the train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star. One thing undoubtedly true in this reasoning is that we cannot get to a star while we are alive, any more than we can take the train when we are dead.

So to me it seems possible that cholera, gravel, tuberculosis, and cancer are celestial means of locomotion, just as steamboats, buses and railways are the terrestrial means. To die quietly of old age would be to go there on foot.”-Vincent van Gogh, Arles, July 16, 1888, Auden, Letters, p. 199.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – repro from artbook, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9513898

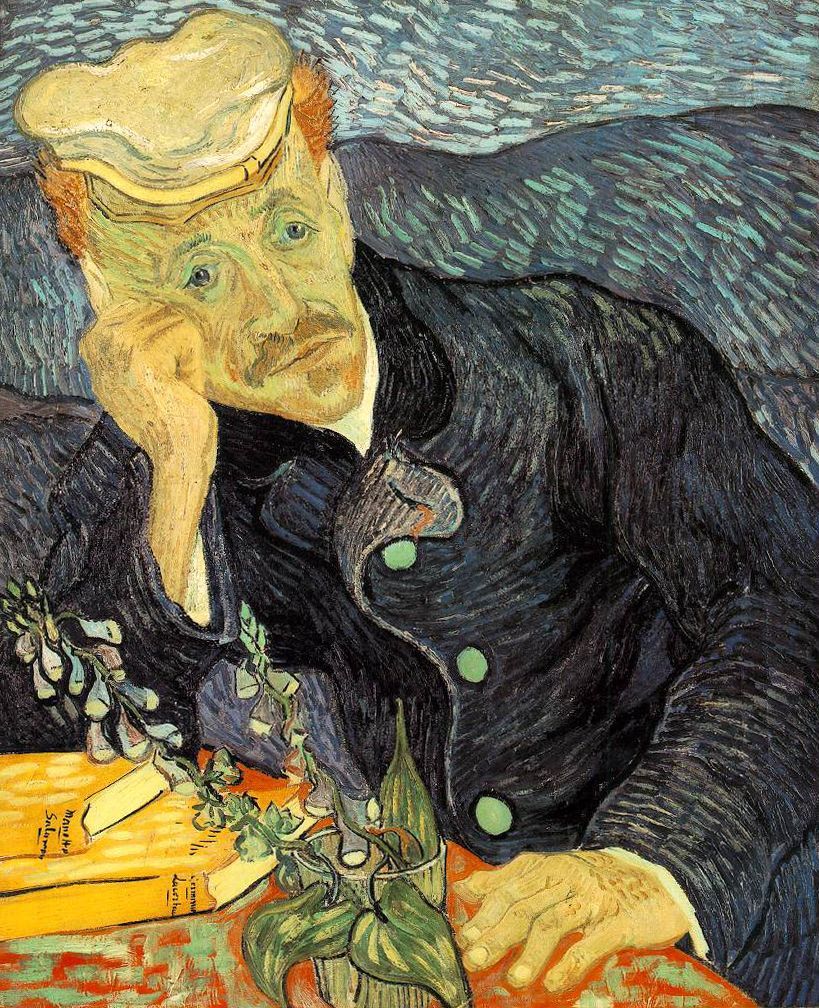

Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet (1828-1909)

Dr. Gachet was a French physician who looked after Vincent Van Gogh during the final months of his life. van Gogh found remarkable similarities between himself and Dr. Gachet; they were in some way like mirror images of each other. Like van Gogh, Gachet suffered from anxiety, melancholia, and more than likely, an addiction to absinthe, an anise-flavoured alcoholic spirit. In a letter to Theo, Vincent recounts his impressions of Dr. Gachet:

I have seen Dr. Gachet, who gives me the impression of being rather eccentric, but his experience as a doctor must keep him balanced enough to combat the nervous trouble from which he certainly seems to me to be suffering at least as seriously as I. I told Dr. Gachet that for 4 francs a day, I should think the inn he had shown me preferable, but that 6 was francs too much, considering the expenses I have. It was useless for him to say that I should be quieter there, enough is enough.

[Dr. Gachet’s] house is full of black antiques, black, black, black, except for the impressionist pictures mentioned. The impression I got of him was not unfavourable. When he spoke of Belgium and the days of the old painters, his grief-hardened face grew smiling again, and I really think that I shall go on being friends with him and that I shall do his portrait.

Then he said that I must work boldly on, and not think at all of what went wrong with me. (Van Gogh, letter to Theo, May, 1890, in Auden (Ed.), Letters, p. 195).

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – Unknown source, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=142046

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – The Courtauld Institute of Art, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29334036

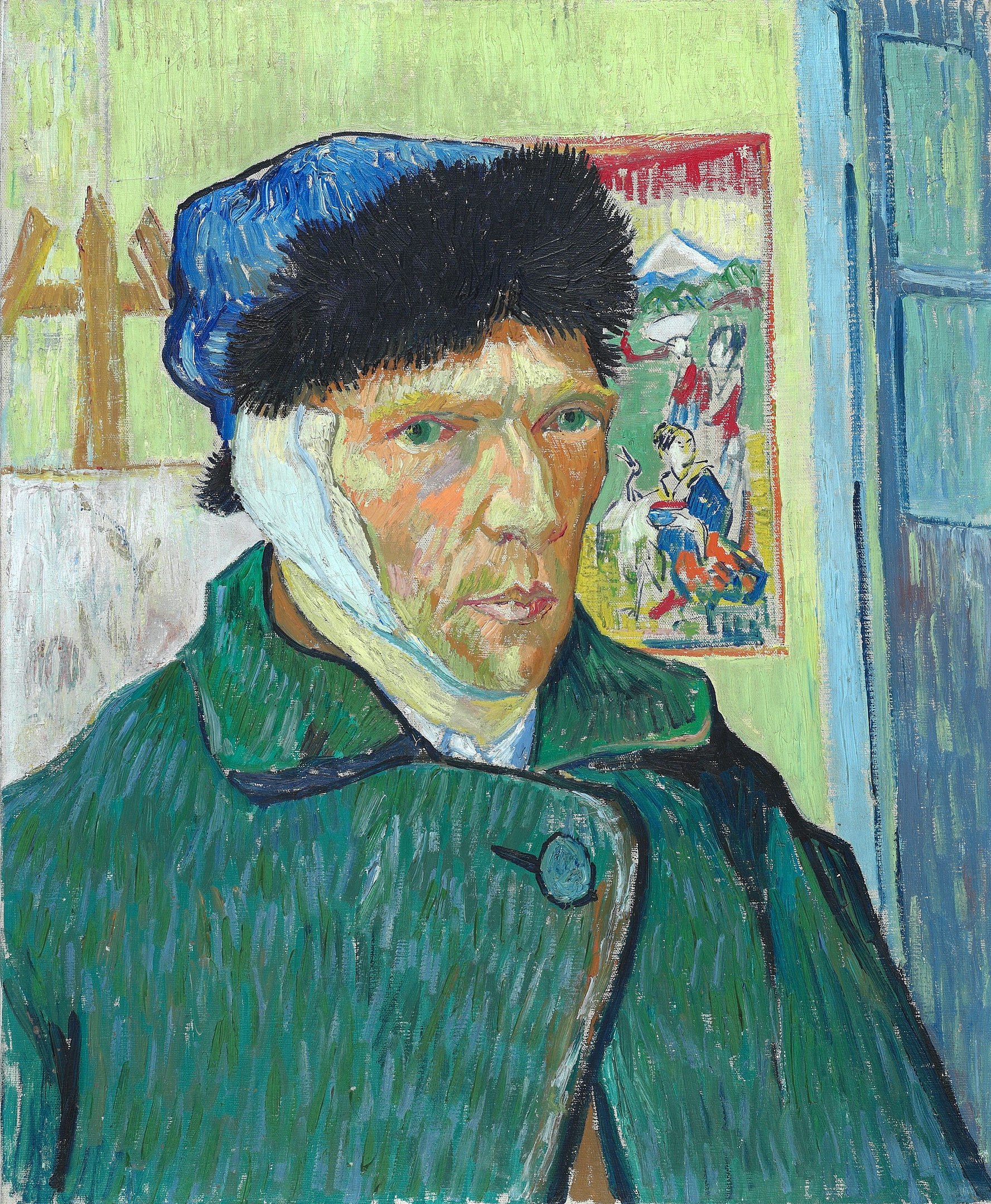

The Cortauld Institute of Art note about van Gogh’s self-portrait with bandaged ear:

“This famous painting, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear by Vincent van Gogh, expresses his artistic power and personal struggles. Van Gogh painted it in January 1889, a week after leaving hospital. He had received treatment there after cutting off most of his left ear (shown here as the bandaged right ear because he painted himself in a mirror). This self-mutilation was a desperate act committed a few weeks earlier, following a heated argument with his fellow painter Paul Gauguin who had come to stay with him in Arles, in the south of France. Van Gogh returned from hospital to find Gauguin gone and with him, the dream of setting up a ‘studio of the south’, where like-minded artists could share ideas and work side by side.

The fur cap van Gogh wears in this painting is a reminder of the harsh working conditions he faced in January 1889: the hat was a recent purchase to secure his thick bandage in place and to ward off the winter cold. This self-portrait is thus powerful proof of van Gogh’s determination to continue painting. It is reinforced by the objects behind him, which take on a symbolic meaning: a canvas on an easel, just begun, and a Japanese print, an important source of inspiration. Above all, it is van Gogh’s powerful handling of colour and brushwork that declare his ambition as a painter.” (The Courtauld Institute of Art Notes)

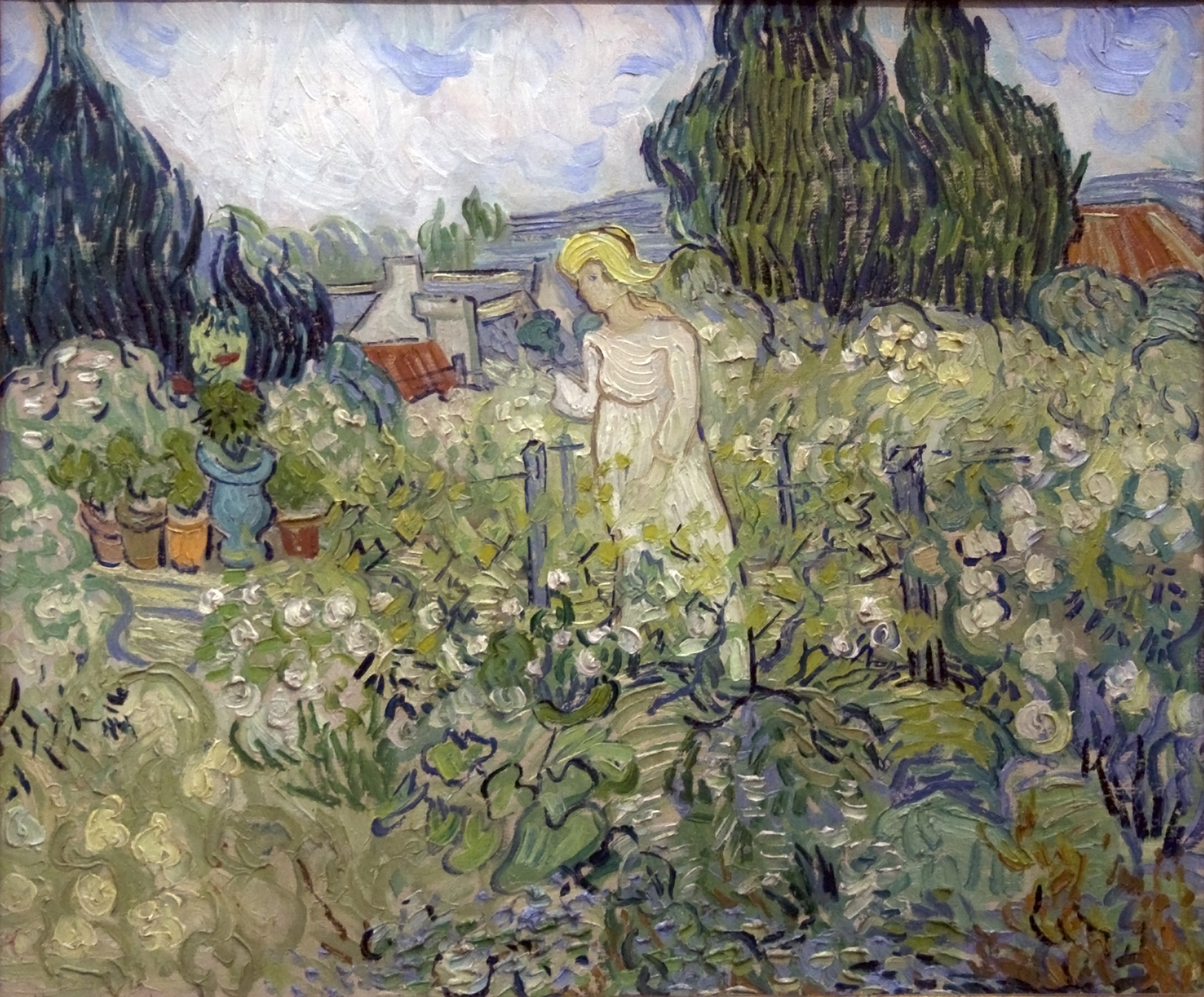

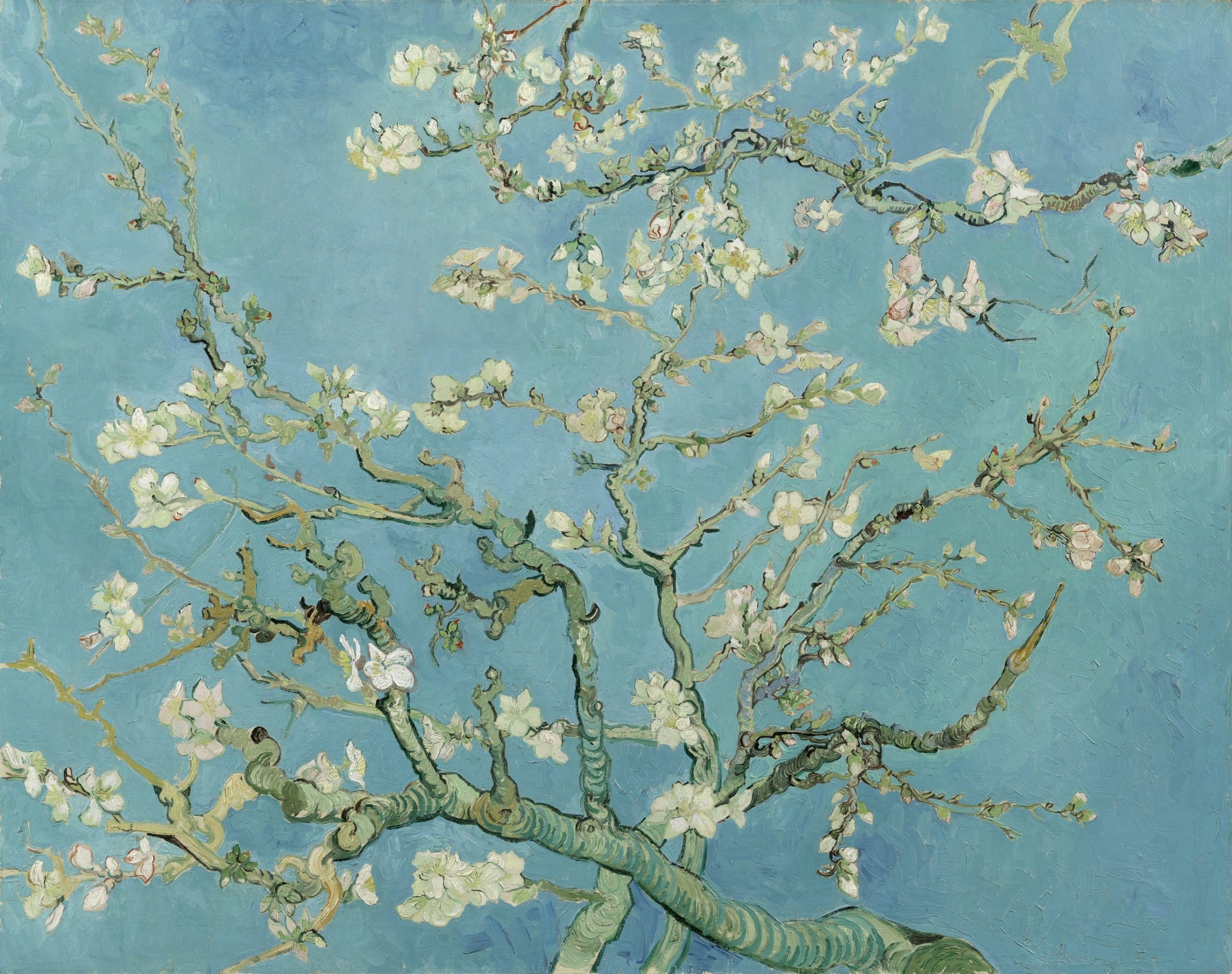

The Garden as a Symbol of Hope

van Gogh saw gardens and flowers as symbols of hope, beauty, harmony, serenity, and joy. Flowers like the irises and sunflowers are often associated with hope, valour, courage, and faith. In his depiction of trees, garden landscapes, flowers, and blossoms, van Gogh was able to experiment with colour, texture, and design. The exhilaration found in painting was in contrast to van Gogh’s emotional suffering. One year before his death, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo:

Well, I with my mental disease, I keep thinking of so many other artists suffering mentally, and I tell myself that this does not prevent one from exercising the painter’s profession as if nothing were amiss…I know well that healing comes—if one is brave—from within through profound resignation to suffering and death, through the surrender of your own will and of your self-love. But that is no use to me, I love to paint, to see people and things and everything that makes our life—artificial—if you like. ( van Gogh in Auden, 1963, Letters, p. 175).

Courtesy: “https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103JNH” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – own photo in the Musée d’Orsay,Paris, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6362678

Sue Roe (2007): The Private Lives of the Impressionists, wrote of Dr. Gachet’s garden:

“Dr. Gachet’s house was set in the hillside above the main street [of the village], with a terraced garden full of flowers and looking down into the valley of the Oise. The house and garden were always full of stray cats, chickens and a ragged, featherless rooster… In the garden, he [Dr. Gachet] worked at a table painted bright orange (p. 109).

For more information about Dr. Gachet, please open the link here.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 4gEx_EL470OSUw at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22006883

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – Copied from an art book, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9101290

A Close Observation of Nature: The Sea in Scheveningen

Vincent van Gogh (1882) letter excerpt to Theo:

“It has been so beautiful in Scheveningen lately. The sea was even more impressive than before the gale, than while it raged. During the gale, one could not see the waves so well, and the effect was less of a furrowed field. The waves followed each other so quickly that one overlapped the other, and the clash of the masses of water raised a spray which, like drifting sand, wrapped the foreground in a sort of haze. It was a fierce storm, and if one looked at it long, even more impressive, because it made so little noise. The sea was the colour of dirty soapsuds. There was one fishing smack on that spot, the last of the row, and a few dark little figures.

There is something infinite in painting—I cannot explain it to you so well—but it is so delightful just for expressing one’s feelings. There are hidden harmonies or contrasts in colours which involuntarily combine to work together and which could not possibly be used in another way. Tomorrow I hope to go and work in the open air again. (van Gogh, 1882, in Auden (Ed.)., Letters, p. 104.)

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – JgGM29jCKH83gQ at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21984976

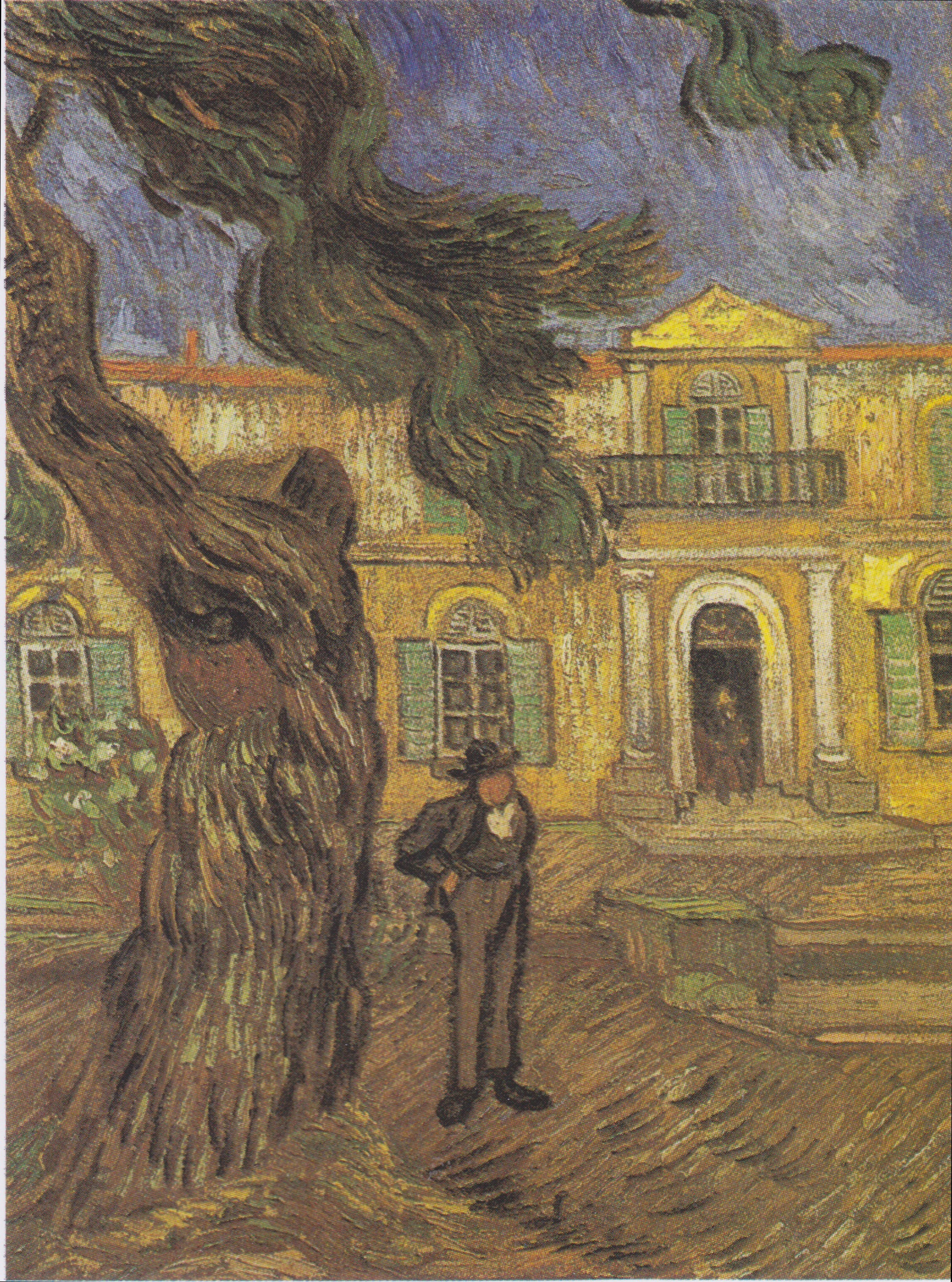

“Here is the description of a canvas which is in front of me at the moment. A view of the park of the asylum where I am staying; on the right a gray terrace and a side wall of the house. Some deflowered rose bushes, on the left a stretch of the park—red-ochre—the soil scorched by the sun, covered with fallen pine needles. The edge of the park is planted with large pine trees, whose trunks and branches are red-ochre, the foliage green gloomed over by an admixture of black. These high trees stand out against an evening sky with violet stripes on a yellow ground, which higher up turns into pin, into green. A wall—also red-ochre—shuts off the view, and is topped only by a violet and yellow-ochre hill. Now the nearest tree is an enormous trunk, struck by lightning and sawed off. But one side branch shoots up very high and lets fall an avalanche of dark green pine needles. The somber giant—like a defeated proud man—contrasts, when considered in the nature of a living creature, with the pale smile of a last rose on the fading bush in front of him. Underneath the trees, empty stone benches, sullen box trees; the sky is mirrored—yellow—in a puddle left by the rain. A sunbeam, the last ray of daylight, raises the somber ochre almost to orange. Here and there small black figures wander around among the tree trunks.” – (Van Gogh, St. Remy, 1889; Auden, p.384)

The Town

“This view…surrounded by fields all covered with yellow and purple flowers….like a Japanese dream.”

“Of the town itself one sees only some red roofs and a tower, the rest is hidden by the green foliage of fig trees, far away in the background, and a narrow strip of blue sky above it. The town is surrounded by immense meadows all abloom with countless buttercups—a sea of yellow in the foreground these meadows are divided by a ditch full of violet irises…. (van Gogh, Letters, Auden, p. 385).”

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – lQFzzpeEHU-XxA — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13523776

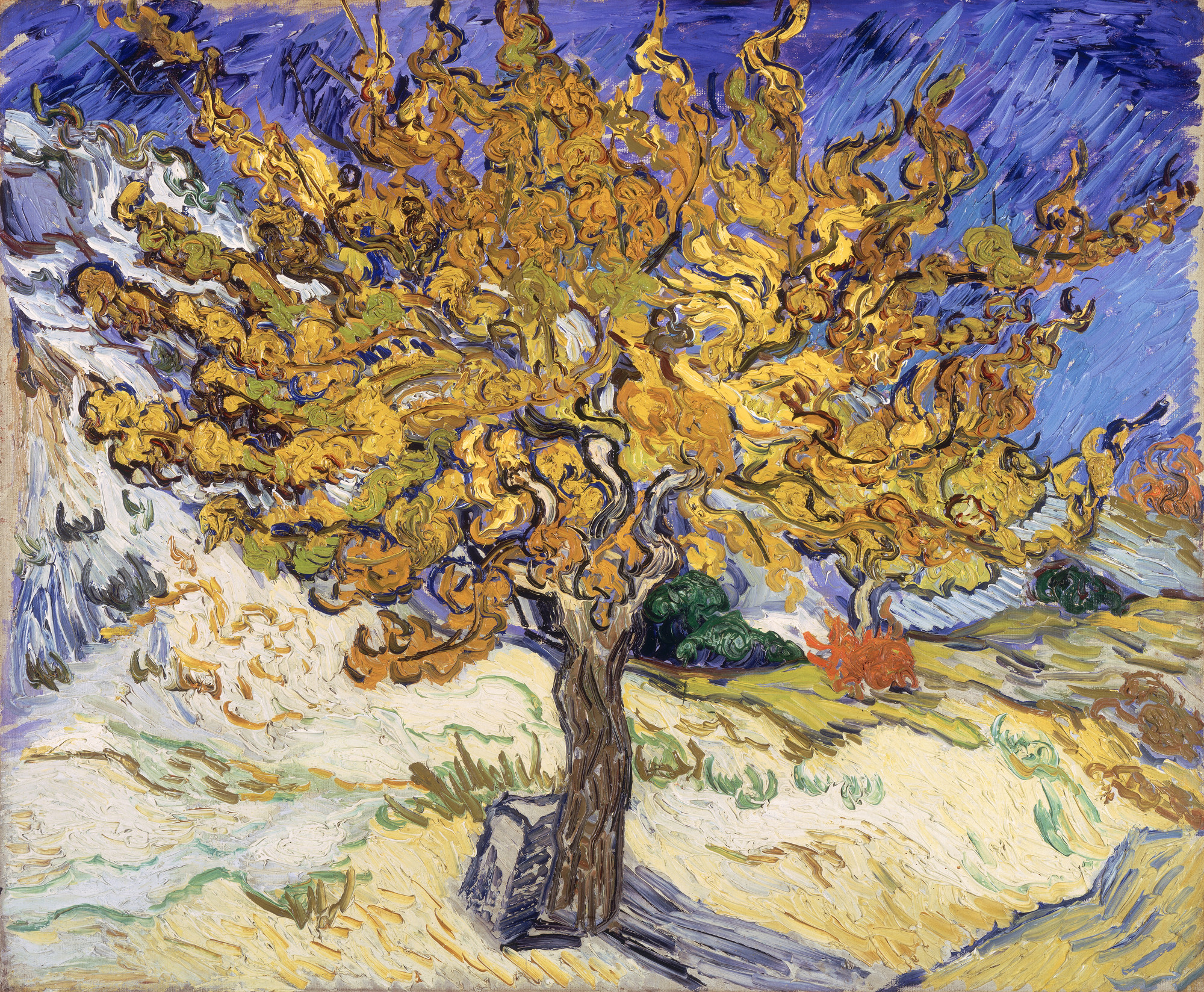

A Dedication to Art and the Search for Meaning and Peace amid Turmoil

The volume of artistic work that Vincent van Gogh completed in his short life was remarkable. The one constant in his life was painting; his art became a mediator between a difficult world and van Gogh’s own inner search for peace and meaning. van Gogh’s life was dedicated to an artistic vision that continues to inspire many. In his painting “The mulberry tree” the tree grows out of a rocky terrain; intense orange, yellow, purple, and blue colours work to create a dynamic landscape where the tree reflects strength and power. Light takes on an almost supernatural glow. The brilliant hues and brush strokes of van Gogh reflect his deep knowledge of colour theory and his insight and sensitivity to nature—seasons, landscapes, people, birds, floral, and fauna. Despite the intense psychological stresses, he found time to paint. van Gogh’s work also reflected his keen awareness of the “modern” direction that painting was going in; in this respect, van Gogh’s was ahead of his time and his work was not appreciated until after his tragic death. van Gogh’s work was visionary and transformative.

“For you cannot imagine any carpet as splendid as that deep brownish-red in the glow of an autumn evening sun, tempered by the trees.

From that ground young beech trees spring up which catch light on one side and are brilliant green there; the shadowy sides of those stems are a warm, deep black-green.

Behind those saplings, behind that brownish-red soil, is a sky very delicate bluish gray, warm, hardly blue, all aglow—and against it all is a hazy border of green and a network of little stems and yellowish leaves…. (Letter to Theo, p. 385 in Auden). ”

For more information about Vincent Van Gogh’s biography, please open this link from the Van Gogh Museum here.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. repro from artbook2. 1000 Museums, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9506304

“The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible, but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore.” – Vincent van Gogh.

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – 1. Hermitage Museum (old web site)2. arthermitage.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1692759

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – www.galeriacanvas.pl, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4400305

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – Copied from an art book, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9387233

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – Van Gogh Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39846909

A Brilliant Mind

Despite his brilliance, acute sensitivity, remarkable talent and love for life, a part of Vincent van Gogh was in deep psychic pain. He saw the beauty in wheat fields, flowers, work, and people but ultimately these talents could not be applied to save himself. van Gogh’s letters and paintings leave a legacy of life that should be cherished, celebrated, and revered. Vincent saw life in mystical ways yet remained alienated and outcast by many, with the exception of his brother Theo van Gogh. The poem “Alone” by Edgar Allen Poe can be connected in many ways to van Gogh’s inner struggles. Both artists made major contributions to culture and art yet they felt misunderstood throughout their lives.

“Alone” by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

From childhood’s hour I have not been

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – bgEuwDxel93-Pg — Google Arts & Culture, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25498286

The Starry Night is based on van Gogh’s direct observations as well as his imagination, memories, and emotions. The steeple of the church, for example, resembles those common in his native Holland, not in France. The whirling forms in the sky, on the other hand, match published astronomical observations of clouds of dust and gas known as nebulae. At once balanced and expressive, the composition is structured by his ordered placement of the cypress, steeple, and central nebulae, while his countless short brushstrokes and thickly applied paint set its surface in roiling motion. Such a combination of visual contrasts was generated by an artist who found beauty and interest in the night, which, for him, was “much more alive and richly colored than the day.

Museum of Modern Art Notes: Reality through an Artist’s Eyes

In a letter to his brother Theo, van Gogh wrote passionately about painting a scene as he experienced, imagined, and, ultimately, interpreted it, not as it was expected to be rendered. Comparing painting to playing music, he argued: “We painters are always asked to compose ourselves and to be nothing but composers. Very well – but in music it isn’t so […] in music […] a composer’s interpretation is something […].”6

Courtesy: By Vincent van Gogh – dAFXSL9sZ1ulDw at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21977493

Additional Resources

- Auden, W.H (1963), van Gogh: A self-portrait: Letters revealing his life as a painter, selected by W.H. Auden. E. P. Dutton & Co.

- Famous Quotes about life, love, and art by Vincent van Gogh.

- Gayford,M. The yellow house and nine turbulent weeks in Arles. Houghton Mifflin.

- Gerakiti, E. (2023). Five Books about Vincent van Gogh. Daily Art Magazine.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: Teaching Resources and Essay on Vincent van Gogh (2023). Open the link here.

- Museum of Modern Art Resources (2023).

- National Council of Teachers of English (2023). Using art to inspire poetry. Lesson Plans.

- Roe, S. (2007). The private lives of impressionists. Harper Collins.

- Readwritethink.org web site (2023). https://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/ekphrasis-using-inspire-poetry

- Small, Z. (2023). “Dream of talking to Vincent van Gogh? A.I. tries to resurrect the artist.” New York Times, Dec. 12, 2023.

- Solomon, D. (2023). van Gogh and the consolation of trees. New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2023 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/11/arts/design/van-gogh-cypresses-met-museum.html

- Stone, I. (1934). Lust for life. Arrow.

- Tashcen (2020). van Gogh: The Complete Paintings.

- The Vangogh Museum Collection – van Gogh Museum

- Please open the link here for more information about Vincent van Gogh.

- To read more about the impact of Vincent van Gogh’s art, please read Deborah Solomon’s 2023 New York Times article here.

- To see a virtual tour of the Van Gogh art museum, please open the link here.

- For a detailed commentary/tour about specific van Gogh masterpieces please open the link here..

- To learn more about Vincent Van Gogh’s experiences in -Auvers-sur-Oise, please open the link here.

Learning Objectives

Activity

Take a walk in a garden or walk around your community and with attention to the natural details around you (trees, buildings, flora, fauna, etc.), describe what you see. Try to apply the close observation detail that van Gogh uses in your own writing. You could also write a letter to van Gogh expressing your thoughts and feelings about his paintings and his life.