40 Well-Known Poems and Art Images

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851). Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore (1834). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States. Courtesy: Widener Collection. “https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.1224.html” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

A Note About “Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore” (National Gallery of Art)

“Turner drew on his considerable experience as a marine painter and the brilliance of his technique as a water colorist to create this view, in which the foundations of the palaces of Venice merge into the waters of the lagoon by means of delicate reflections. He based the composition on a rather slight pencil drawing made during his first trip to Venice, in 1819, but the painting is really the outcome of his second visit, in 1833. He exhibited this canvas to wide acclaim at the Royal Academy, London, in 1835.”

You can find more information about the art of John M.W. Turner here.

“Ode On Venice” by George Gordon Byron

I.

Oh Venice! Venice! when thy marble walls

Are level with the waters, there shall be

A cry of nations o’er thy sunken halls,

A loud lament along the sweeping sea!

If I, a northern wanderer, weep for thee,

What should thy sons do?–anything but weep

And yet they only murmur in their sleep.

In contrast with their fathers–as the slime,

The dull green ooze of the receding deep,

Is with the dashing of the spring-tide foam

That drives the sailor shipless to his home,

Are they to those that were; and thus they creep,

Crouching and crab-like, through their sapping streets.

Oh! Agony-that centuries should reap

No mellower harvest! Thirteen hundred years

Of wealth and glory turn’d to dust and tears;

And every monument the stranger meets,

Church, palace, pillar, as a mourner greets;

And even the Lion all subdued appears,

And the harsh sound of the barbarian

With dull and daily dissonance, repeats

The echo of thy tyrant’s voice along

The soft waves, once all musical to song,

That heaved beneath the moonlight with the throng

Of gondolas–and to the busy hum

Of cheerful creatures, whose most sinful deeds

Were but the overbeating of the heart,

And flow of too much happiness, which needs

The aid of age to turn its course apart

From the luxuriant and voluptuous flood

Of sweet sensations, battling with the blood….

You can find The Complete Poetical Works of Lord Byron (Macmillan Co. Publishing, 1907) here.

“Sailing to Byzantium” by William Butler Yeats

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees,

—Those dying generations—at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

II

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

III

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

Further Resource:

“Celebrated J.M.W. Turner Exhibit Comes to Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario” by Nigel Hunt (CBC Arts, 2015)

Excerpt from “The Highwayman” by Alfred Noyes

PART ONE

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees.

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding—

Riding—riding—

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

He’d a French cocked-hat on his forehead, a bunch of lace at his chin,

A coat of the claret velvet, and breeches of brown doe-skin.

They fitted with never a wrinkle. His boots were up to the thigh.

And he rode with a jewelled twinkle,

His pistol butts a-twinkle,

His rapier hilt a-twinkle, under the jewelled sky.

Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard.

He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred.

He whistled a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

And dark in the dark old inn-yard a stable-wicket creaked

Where Tim the ostler listened. His face was white and peaked.

His eyes were hollows of madness, his hair like mouldy hay,

But he loved the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s red-lipped daughter.

Dumb as a dog he listened, and he heard the robber say—

“One kiss, my bonny sweetheart, I’m after a prize to-night,

But I shall be back with the yellow gold before the morning light;

Yet, if they press me sharply, and harry me through the day,

Then look for me by moonlight,

Watch for me by moonlight,

I’ll come to thee by moonlight, though hell should bar the way.”

He rose upright in the stirrups. He scarce could reach her hand,

But she loosened her hair in the casement. His face burnt like a brand

As the black cascade of perfume came tumbling over his breast;

And he kissed its waves in the moonlight,

(O, sweet black waves in the moonlight!)

Then he tugged at his rein in the moonlight, and galloped away to the west.

PART TWO

He did not come in the dawning. He did not come at noon;

And out of the tawny sunset, before the rise of the moon,

When the road was a gypsy’s ribbon, looping the purple moor,

A red-coat troop came marching—

Marching—marching—

King George’s men came marching, up to the old inn-door.

They said no word to the landlord. They drank his ale instead.

But they gagged his daughter, and bound her, to the foot of her narrow bed.

Two of them knelt at her casement, with muskets at their side!

There was death at every window;

And hell at one dark window;

For Bess could see, through her casement, the road that he would ride….

You can find the complete poem here.

“The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas” – Alfred Noyes, “The Highwayman,” 1906

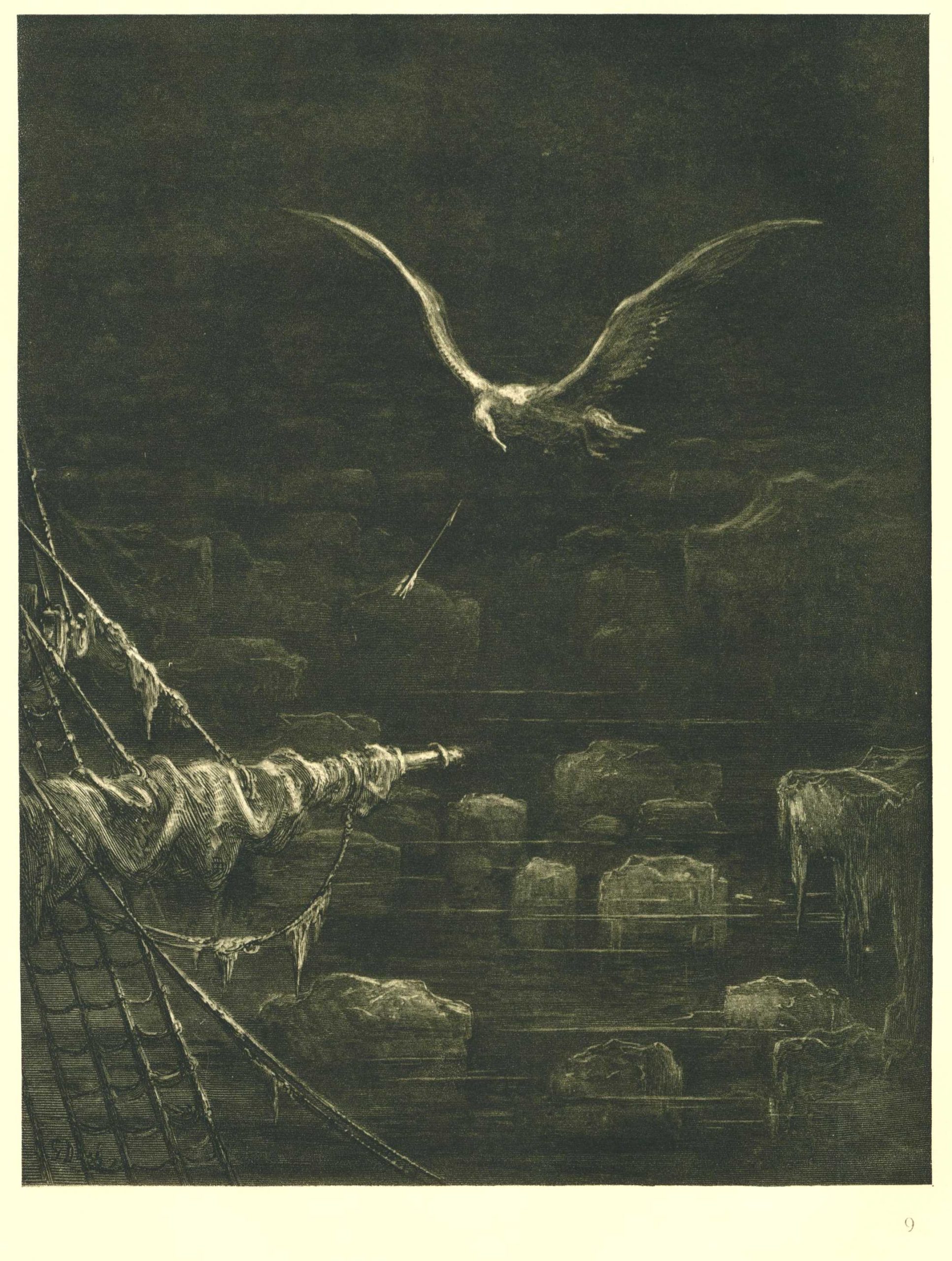

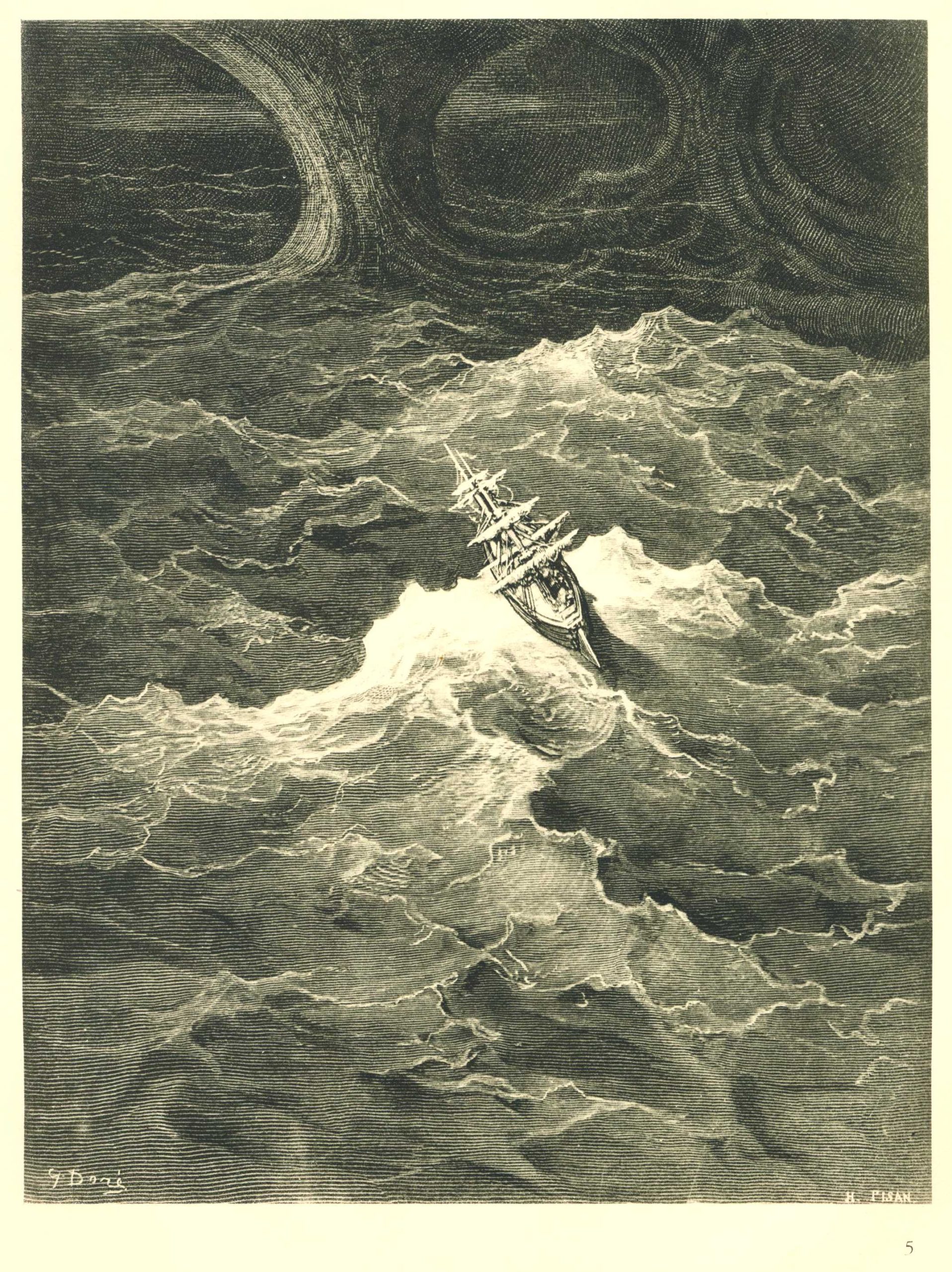

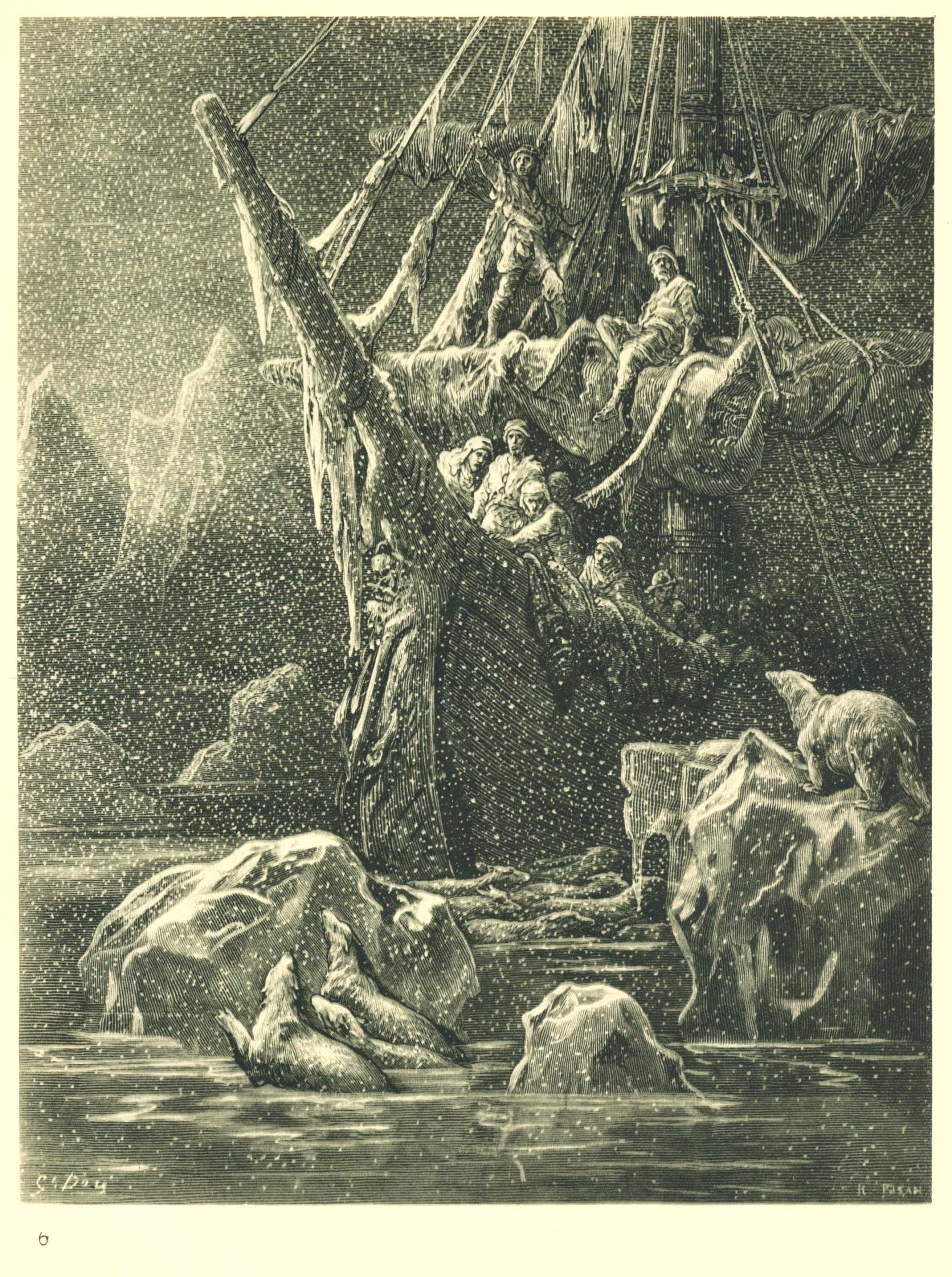

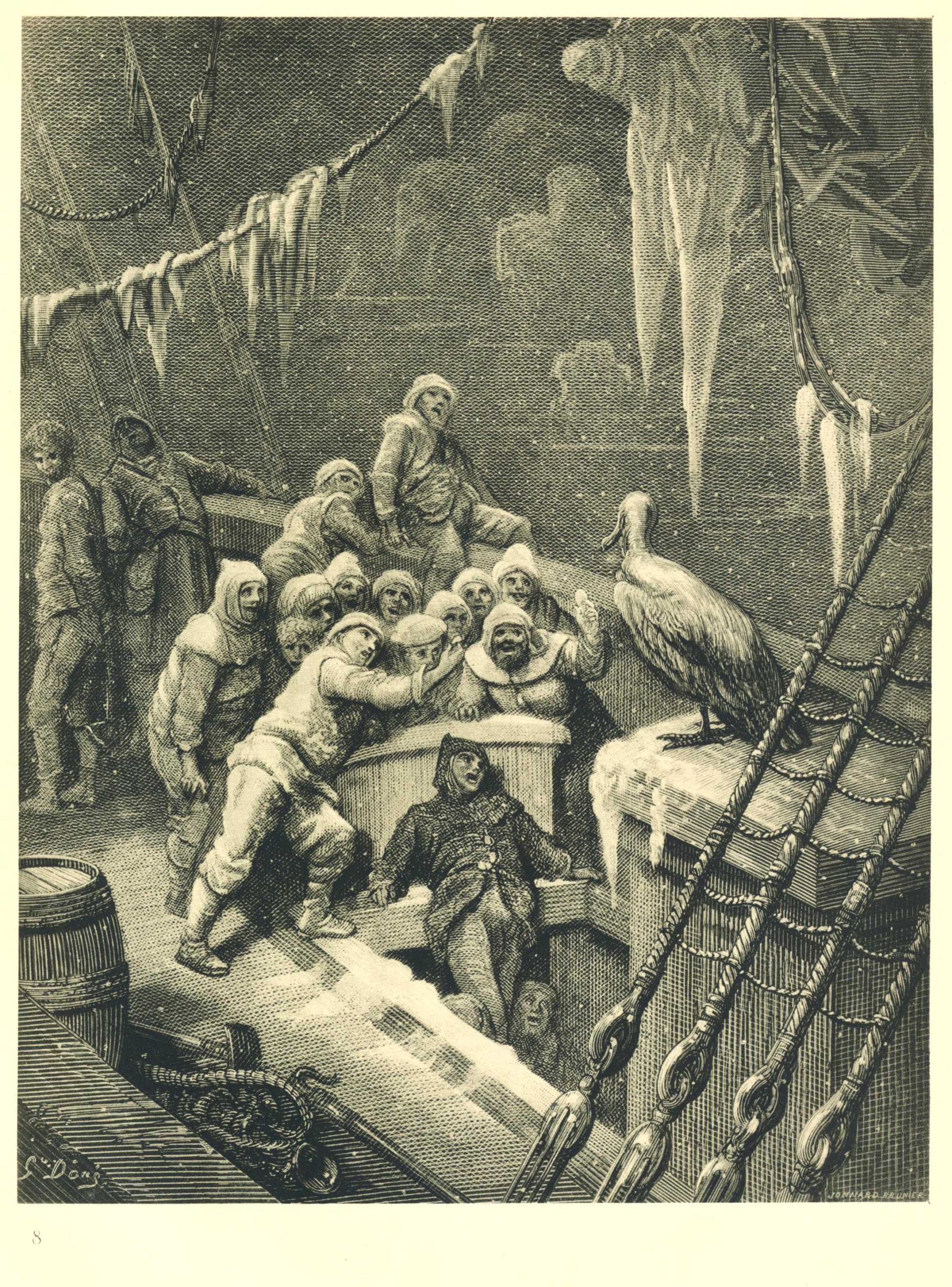

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

“Water, water, everywhere, and all the boards did shrink; water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (lines 119-120)

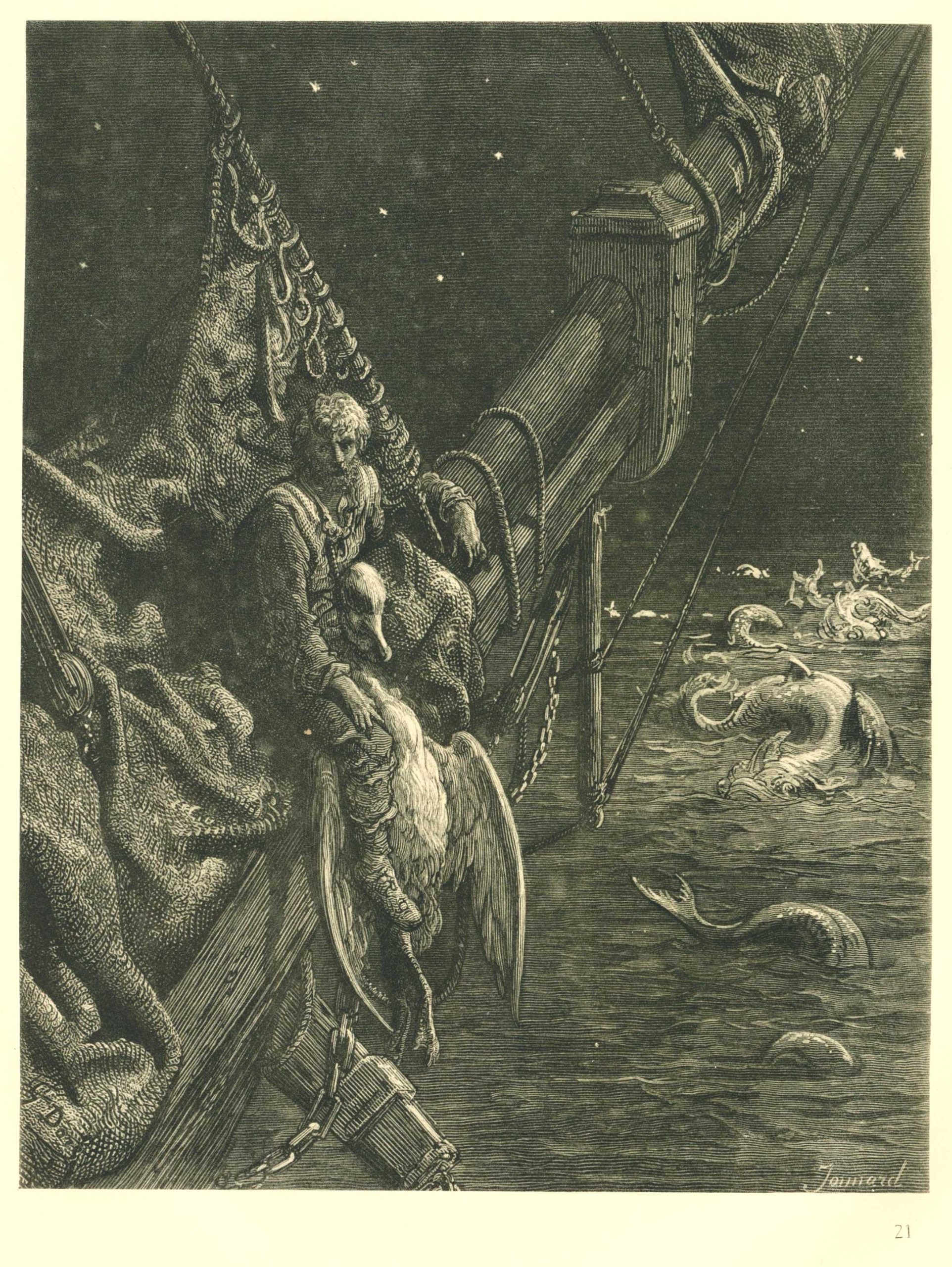

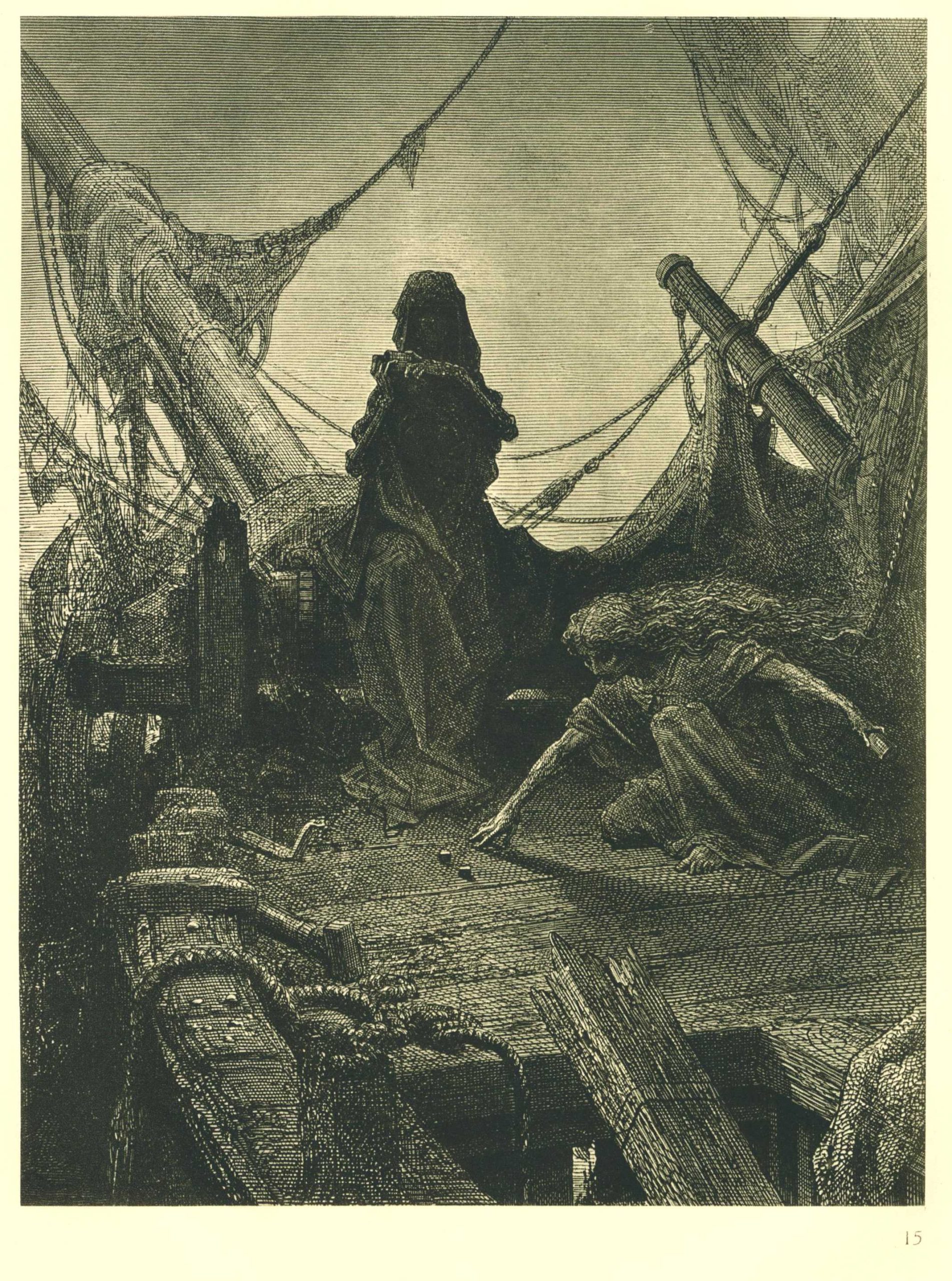

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” is Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s longest major poem. The poem is written in a ballad form in seven parts that first appeared in Lyrical Ballads, published collaboratively by Coleridge and William Wordsworth in 1798. The poem was written in 1797 and the poem represents a shift to modern poetry and the beginning of the age of British Romantic literature. Coleridge uses a narrative style to recount the uncanny experiences of a sailor who returned from a long sea voyage. Using vivid description to create suspense and elements of the supernatural, the mariner recounts his experiences to a man who is on his way to a wedding ceremony. In the narrative, the mariner describes seeing an albatross, often viewed by sailors as a good omen. The albatross is viewed as a protective, hopeful, and angelic force that leads the ship crew out of danger and into calmer and more temperate waters. Rather than appreciating the bird, the mariner shoots the bird with his cross bow and kills it. Believing that a curse has now befallen the mariner and his crew, the mariner is forced to wear the albatross around his neck as a reminder of his cruelty. The mariner comes to feel extreme remorse for killing the beautiful albatross. Events lead the mariners and crew to uncharted waters where the crew encounters a ghost ship:

On board are Death (a skeleton) and the ‘Night-mare Life-in-Death’ (a deathly pale woman), who are playing dice for the souls of the crew. Death wins the lives of the crew members and Life-in-Death the life of the Mariner, a prize she considers more valuable. Her name is a clue as to the Mariner’s fate…he will endure a fate worse than death as punishment for his killing of the albatross. As penance for shooting the albatross, the Mariner, driven by guilt, is forced to wander the earth, tell his story, and teach a lesson to those he meets: He prayeth best, who loveth best All things both great and small; For the dear God who loveth us, He made and loveth all. After relating the story, the Mariner leaves, and the Wedding Guest returns home, waking the next morning “a sadder and a wiser man”.

The poem is psychologically complex in its portrayal of fear, guilt, remorse, loss, longing, and redemption.

(Adapted from the Victoria and Albert Museum)

The French artist Gustave Doré (1832–1883) created a series of powerful illustrations that correspond to different parts of the mariner’s narrative. The 1982 edition was published in Leipzig, Germany, eighty years after the first publication. Dore’s art evoked elements of the romantic, the grotesque, supernatural, the mystical, and the fantastic. Dore’s vivid illustrations combined with Coleridge’s superb narrative poetry made this poem a classic. The themes of death, fate, mystery, regret, loss, and the power of nature continue to resonate today.

Further Resources:

“The Ancient Mariner” illustrations by Gustave Doré (The British Library)

More illustrations from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” can be found here, here, here, here, and here.

Biography of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Modern Critical Interpretations: Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom (Chelsea House Publishers, 1986)

Illustrations by Gustave Doré

Courtesy: By Gustave Doré – DER ALTE MATROSE mit Bildern von Gustav Doré, von Ferdinand Freiligrath, nach dem Englischen von S. T. Coleridge. Verlag Josef Müller, München, 1925 (self scanned from book), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21520099

Part One of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

PART THE FIRST.

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

He holds him with his skinny hand,

“There was a ship,” quoth he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!”

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

He holds him with his glittering eye—

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the light-house top.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon—

The Wedding-Guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry minstrelsy.

The Wedding-Guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

And now the STORM-BLAST came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with his o’ertaking wings,

And chased south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

And now there came both mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold:

And ice, mast-high, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken—

The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

At length did cross an Albatross:

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

It ate the food it ne’er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon-shine.

“God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—

Why look’st thou so?”—With my cross-bow

I shot the ALBATROSS.

Courtesy: By Gustave Doré – DER ALTE MATROSE mit Bildern von Gustav Doré, von Ferdinand Freiligrath, nach dem Englischen von S. T. Coleridge. Verlag Josef Müller, München, 1925 (self scanned from book), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21520067

Excerpt from Part Three of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Are those her ribs through which the Sun

Did peer, as through a grate?

And is that Woman all her crew?

“Is that a DEATH? and are there two?

Is DEATH that woman’s mate?

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The Night-Mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she,

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice;

“The game is done! I’ve won! I’ve won!”

Quoth she, and whistles thrice…..”

Excerpt from Part Five of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air=

With their sweet jargoning!

And now ’twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel’s song,

That makes the Heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

Phantom and Ghost Ships: The Legends of The Mary Celeste and The Flying Dutchman (Canadian Encyclopedia)

Many legends of so-called phantom and ghost ships have their mysterious origins in true stories. The perils of the seas and oceans were well-known to sailors and their families. The stories of The Mary Celeste and The Flying Dutchman reflect, in essence, existential themes that center around the fragility of life, loss, death, and the power of nature to alter an individual’s fate. Originally named the Amazon, the Mary Celeste was a ship built in 1861 in Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia. In 1872 the Mary Celeste was found drifting off the shores of the Azores islands. There were no crew members about and their mysterious fate became the source of legends and ghost stories. The Flying Dutchman was thought to be a ghost ship that would never reach home but was doomed to continue sailing the seas forever. This legend originated during the so-called 17th century “Golden Age” of Dutch marine power and colonization. During this time, some of the cargo ships of the Dutch East India Company never returned; it was thought that the crew met their fate in perilous seas or in unexplained ways. Legend had it that if sailed saw the ghostly glow of the Flying Dutchman ship, imminent disaster was near.

The fate of both The Flying Dutchman and The Mary Celeste led to poems, works of art, films, and tales of the uncanny and supernatural.

You can read more about The Legend of the Mary Celeste here and here. You can read about The Flying Dutchman here.

You can read Sea Phantoms: Or, Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors in All Lands and at All Times by Fletcher Bassett (1892) here.

Excerpt from “The Flying Dutchman” by John Boyle O’Reilly

There, beyond the Cape of Storms,

Where the breaker’s voice of thunder

Roars when ships are rent asunder,

Through a fog of ghostly forms

Men catch glimpses of the sail,

Ages old, and rent and hoary,

Of that quaint old ship of story,

And cry, ‘Vanderdecken, hail!’

You can read the complete poem here.

Excerpt from The Book of The Ocean by Ernest Ingersoll

Erik the Red and the Discovery of Greenland

“At any rate, Erik had little hesitation in starting out to rediscover them. Why should he? Those rough-riders of the sea were used to voyages of equal length. It is about 200 miles from the Norwegian coast at Bergen to the Shetland Islands; 200 miles from the Shetlands, or 225 from the Hebrides, to the Faroes; and 275 miles thence to the nearest coast of Iceland,—reckoning all in straight lines, shorter than any ship could actually follow.

If his viking boat and viking crew could span those stretches of sea unguided, what hindered his crossing the little further space whose tempests had no terrors for this wild sea-king? In that unpossessed land, could he find it, he might be free to riot at his will (but one cannot help thinking there was more in the man than that!); and if he could open to his people a new country, what wealth and power might not come with it to him, for the humbling of his rivals at the court of Norway.

So Red Erik sailed away to the west in 984, and two years later returned to Iceland and reported that he had met first a far-extending icy coast, along whose front he had sailed southward until he could turn to the west and then northward, thus rounding its narrow southern extremity (Cape Farewell); and there he had found a habitable region, which he called Greenland, in order, as he said, to attract settlers by a pleasant name. Thus this wicked old Norseman was the first of American “real-estate boomers.”

Attracted by his story, a band of adventurers went back with him in 986, and established a settlement near the site of the present Danish town Julianshaab, just inside the cape, on an inlet that they named Eriksfiord.

Ernest Ingersoll’s The Book of the Ocean conveys a message of the ocean’s bounties; there was little awareness of the harm that would result in centuries of overfishing and exploitation of the oceans. Sea exploration was an adventure, albeit a risky and dangerous one. Writers like Ingersoll presented “discovery” and “exploration” in ways that did not factor in Indigenous lives, land dispossession, and resource depletion. The seas are described as having abundant resources. It is valuable to consider the attitudes toward nature as a source either to be respected or exploited (past, present, and future to be determined). The discovery of the Banks of Newfoundland’s abundant store of cod fish is noted in this passage fromThe Book of the Ocean:

We can imagine with what eagerness his story was listened to, as he told of the fair, temperate, well-wooded land, its people and animals and fruitfulness, that he had seen. But the thing that impressed the Bristol men most was the report of the enormous abundance of codfish there. This was something these canny men could see without any illusions, and possess themselves of regardless of papal bulls; and they at once abandoned68 their northern fishing-grounds and began to resort to the Banks of Newfoundland, whither they were quickly followed by large annual fleets of Norman, Breton, Spanish, and Portuguese fishermen. John Cabot intended to go again the next year and make his way onward to Japan, as he believed he could do, for, like the others, he thought what he had found was only a remote eastern part of Asia; and in 1498 he actually did sail westward from Bristol with five ships, victualed for a year. None of these ships ever returned, and no evidence exists that they ever reached their goal; and with them John Cabot, to whom England owed her early supremacy in North America, disappears from view.

Sebastian Cabot was a son of John Cabot, and a skillful map-maker. Whether he went with his father on the first voyage is disputed; there seems no direct evidence that he did so. That he did not go on the second voyage is plain, for he had a long subsequent career, of which accurate knowledge is a late acquisition; here it is only necessary to add that by his statements to Peter Martyr and others he allowed the erroneous impression to pass into history, if he did not directly authorize the lie, that it was he, and not his father, who discovered America and the fishing-grounds …

“Dover Beach” by Matthew Arnold

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay;

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanch’d land,

Listen! You hear the grating roar

Of Pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round the earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing, roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! For the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Further Resources:

Dancing in the Wind: Poetry and Art of the British Isles by C. Sullivan (Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2002)

A description of “Dover Beach” by Matthew Arnold can be found here.

This painting (Oil on canvas, 28.8 x 37.2 cm) by E.W. Cocks shows the first balloon crossing of the English Channel by Blanchard and Jeffries on January 7, 1785. You can see the balloon above Dover Castle and harbour, with an anachronistic paddlesteamer.

“Deep Sea Calm” by Hardwicke Rawnsley

With what deep calm, and passionlessly great,

They central soul is stored, the Equinox

Roars, and the North Wind drives ashore his flocks,

Thou heedest not, thou dost not feel the weight.

Of the Leviathan, the ships in state

Plough on, and hull in battle shocks,

Unshaken thou; the trembling planet rocks,

Yet thy deep heart will scarcely palpitate.

Peace-girdle of the world, the face is moved.

And now the furrowed brow with fierce light gleams,

Now laughter ripples forth a thousand miles,

But still the calm of thin abysmal streams

Flowers round the people of our fretful isles,

And Earth’s inconstant fever is reproved.