Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

5 The Odyssey in Selected Art Images, Poetry, and Prose

The Odyssey in Selected Art Images, Poetry, and Prose

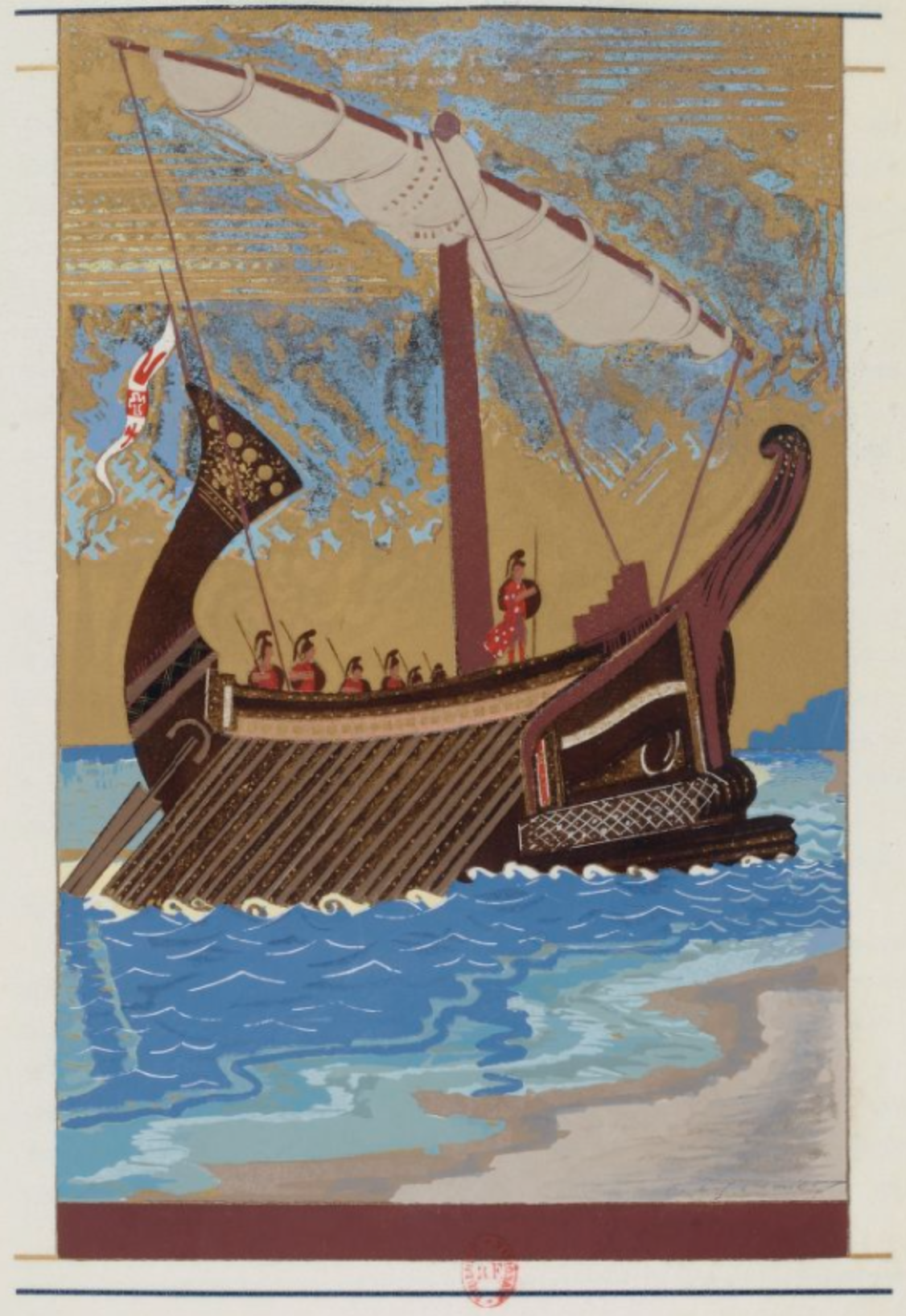

Francois-Louis Schmied, Illustration for The Odyssey by Homer. Paris, Compagnie des bibliophiles de l’Automobile-Club de France, 1928, volume 1, page 113. 1928, Vol. 1, p. 113, Bibliotheque nationale de France. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schmied_illustration_Odyss%C3%A9e-CompBibliophilesAutoClubFrance-1932vol1p113.png

Homer’s The Odyssey and Voyages of Ulysses in Art, Poetry, and Prose: Selected Images

Ulysses on Calypso’s Island

Ditlev Blunck (1798-1853), Ulysses on Calypso’s Island. 1830. Oil on canvas. Flensburg Museum, Germany. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Museumsberg-flensburg-pi26619_1.jpg

Key Takeaways

Homer’s The Odyssey is an epic poem written by Greek poet Homer during the 8th century. Twenty four “books” form this classic epic poem. Along with The Iliad (an epic poem about the 10-year siege of Troy by the Greek city states), The Odyssey remains one of the great classic works that continues to inspire artists, film makers, poets, and writers. Ovid’s Metamorphoses and other classical works draw from Homer’s epics. There are many exceptional translations of The Odyssey that include beautiful illustrations. For some examples please open the links below:

The Odyssey was translated into English Prose by Samuel Butler in 1897. The Project Gutenberg e-book can be accessed with the link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1727/1727-h/1727-h.htm

Summary:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odyssey

The Odyssey in Art (Photo Essay)

https://eclecticlight.co/2021/11/05/homers-odyssey-in-paintings-1-polyphemus-and-circe/

Illustrations for The Odyssey by Francois Louis Schmied:

Rogmanoli Illustrations:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Illustrations_from_Odissea_(Romagnoli)

Walter Paget Illustrations:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Illustrations_from_%27La_Odisea%27_by_Walter_Paget

The hero of The Odyssey is Ulysses, King of Ithaca and his 10 year adventure on his way home from the Troy back to Ithaca. Selected art, poetry, and prose images in this section highlight Ulysses’s death -defying and perilous experiences meeting supernatural and fantastical creatures, monsters, gods, demi-gods, and sorceresses. The art images, poetry, and prose featured in this section depict Ulysses and some of his men escaping from the Cyclops Polyphemus as well his visits to the enchantress Circe with whom Ulysses and his men stay feasting for one year. Barely escaping the treacherous monsters Scylla (a six headed monster) and Charybdis (a destructive whirlpool). Landing on the island of Thrinacia, Ullyses’s men slaughter the sun-god’s cattle; as a result, Zeus (Jupiter) destroyed their ship, and Ulysses is stranded on Calypso’s isle. Calypso and the Phaeacians along with the goddess Athena help Ulysses return safely to Ithaca where Ulysses’s spouse Penelope had continued to wait. Earlier Telemachus (Ullysses’s son) set forth on a journey to find his father.

In Alfred Lord Tennyson’s (1809-1892) dramatic monologue “Ulysses,” the Greek hero is restless and longs to return to his life of adventure and risk. Ulysses does not want to remain idle on a “barren” crag “matched with an aging wife” and people that “hoard and know not me.” In Tennyson’s poem, Ulysses’s quest for new knowledge, courage, and willingness to defy the odds signifies a universal message of hope amid despair. It is never too late to seek new learning experiences and create a new life chapter.

Source: “Ulysses” by Alfred Lord Tennyson: All Poetry Website:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45392/ulysses

Summary and Notes about the poem: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulysses_(poem)

Odysseus’s Adventure: Selected Art, Poetry, and Prose

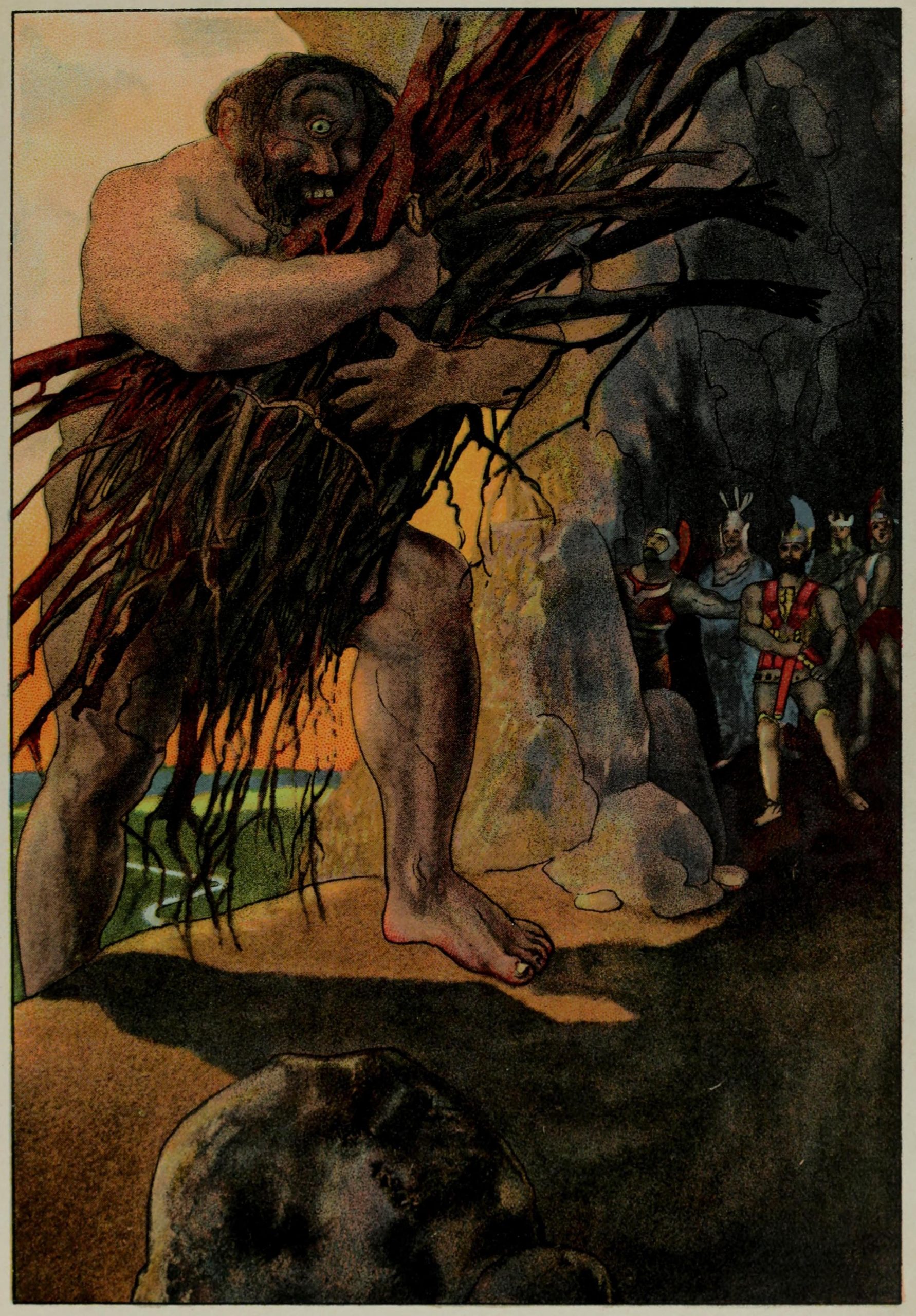

“He was a horrid creature, not like a human being at all, but resembling rather some crag, that stands out boldly against the sky on the top of a high mountain” (Butler, Homer’s The Odyssey, p. 107. Three River Press).

One-Eyed Polyphemus

Marshall Logan, One-Eyed Polyphemus, In The Odyssey. 1914. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/The_one_eyed_Polyphemus.jpg

*The one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus’s name means “abounding in songs and legends”, “many-voiced” or “very famous” (Asimov, Words from the Myths, Signet, 1969).

From Book IX of The Odyssey: Polyphemus meets Ulysses and his Men:

“When the [cyclops] got through with all his work, he lit the fire, and then caught sight of us, whereon he said;

“Stranger, who are you?” Where do you sail from? Are you traders, or do you sail the sea as rovers, with your hands against every man, and every man’s hand against you?”

“We were frightened of our senses and his loud voice and monstrous form but I managed to say: ‘We are Achaeans on our way home from Troy, but by the will of Zeus and stress of weather we have been driven far out of our course. We are the people of Agamemnon son of Atreus, who has won infinite renown throughout the whole world by sacking so great a city and killing so many people. We therefore humbly pray you to show us some hospitality, and otherwise make us such presents as visitors may reasonably expect. May your excellency for the wrath of heaven, for we are your suppliants, and Zeus takes all respectable travelers under his protection, for he is the avenger of all suppliants and foreigners in distress.” (The Odyssey, p. 109).

Rather than help Ulysses and his crew, Polyphemus begins to kill Ulysses’s men. Later, Ulysses devises a plan and instructs his men to hide under the sheep and escape when Polyphemus lets the flock out of the cave in the morning.

For more information, please follow the sources below:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/The_one_eyed_Polyphemus.jpg

Odysseus and his Men Trying to Escape from Polyphemus’s Cave

Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), Odysseys and his men trying to escape from Polyphemus’s cave hidden under rams (painted between 1660-1665).

Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jakob_Jordaens_009.jpg

Odysseus and Polyphemus

Arnold Bocklin (1827–1901). Odysseus and Polyphemus. 1896. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. Public Domain. https://collections.mfa.org/download/564102;jsessionid=4CE5F50153F16E328E3BB851C10A9AAB

Polyphemus

“[Polyphemus] got more and more furious as he heard me, so he tore the top off from a high mountain, and flung it in front of my ship so that it was within a little of hitting the end of the rudder. The sea quaked as the rock fell into it, and the wash of the wave it raised carried u back toward the mainland, and forced us toward the shore. But I snatched up a long pole and kept the ship off, making signs to my men by nodding my head, that they must row for their lives, whereon they laid out with a will. When we had got twice as far as we were before, I was for jeering at the Cyclops again, but my men begged and prayed of me to hold my tongue (The Odyssey, Book IX, Butler, p. 115). “

Samuel Butlern (1835-1902) translated Homer’s The Odyssey in 1900.

Circe the Sorceress

Frederick Stuart Church (1842-1924), Circe and the Enchanted Lions. 1909. Oil on Canvas, Gift of William T. Evans, Courtesy of the Smithsonian Art Galleries, Washington, DC. Public Domain.

http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=4809

Ulysses at Circe’s Palace

Carl Borromaus Andrea Ruthart (1626-1679). Painting formerly attributed to Jan Van Kessel the Elder. Ulysses at Circe’s Palace, Getty Centre, Los Angeles, CA. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Brant. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Schubert_Ulysses_and_Circe.jpg

Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses. 1891. Oldham Art Gallery, Manchester, England. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d9/Circe_Offering_the_Cup_to_Odysseus.jpg

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), Circe Offering the Cup to Ulysses. 1891. Oldham Art Gallery, Manchester, England. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d9/Circe_Offering_the_Cup_to_Odysseus.jpg

Excerpt from Book 10 of The Odyssey

“When they reached Circe’s house they found it built of cut stones, on the site that could be seen from far, in the middle of the forest. There were wild mountain wolves and lions prowling all around it— poor bewitched creatures whom she tamed by her enchantments and drugged into subjection. They did not attack my men, but wagged their great tails, fawned upon them, and rubbed their noses lovingly against them…Presently they reached the gates of the goddess’s house, and as they stood there they could hear Circe within, singing most beautifully as she worked her loom, making a web so fine, so soft, and of such dazzling colour as no one but a goddess could weave…..(The Odyssey trans. By Samuel Butler, p. 123, Fall River Press, 2018). (published originally in 1897).

Circe Invidiosa

John William Waterhouse (1849-1916), Circe Invidiosa. 1891. Art Gallery of South Australia, South Terrace, Adelaide, Australia. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Circe_Invidiosa_-_John_William_Waterhouse.jpg

The Wine of Circe

Edward Burne Jones (1833-1898). The Wine of Circe. 1900. Birmingham Art Gallery and Museum, Birmingham, UK. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/Edward_Burne-Jones_-_The_Wine_of_Circe%2C_1900.jpg’

(Notes: Illustration for The Outline of Literature by John Drinkwater, Newnes, 1900. Photogravure on paper; Smithsonian Art Museum, Washington, DC).

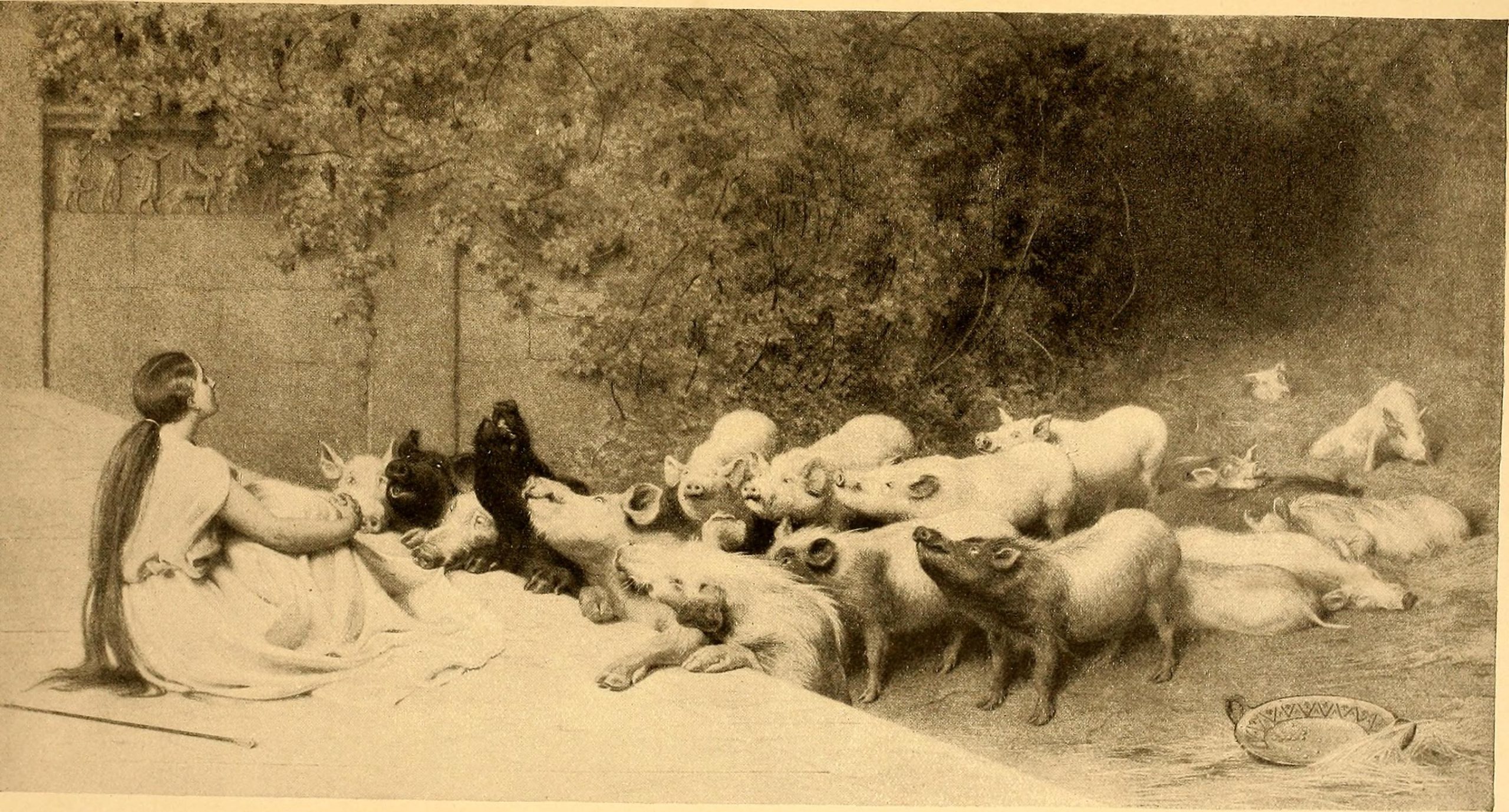

Circe transformed Ulysses’ crew into swine:

After drinking Circe’s wine and other potions, the men were turned into swine:

“[The men] called her and [Circe] came down, unfastened the door, and bade them enter. They, thinking no evil, followed her, all except Eurylochus, who suspected mischief and stayed outside. When she had got them into her house, she set them upon benches and seats and mixed them with a mess with cheese, honey, meal, and Pramnian wine, but she drugged it with wicked poisons to make them forget their homes, and when they had drunk she turned them into pigs by a stroke of her wand, and shut them up in her pigsties. There were like pigs—head, hair, and all, and they grunted just as pigs do; but their senses were the same as before and they remembered everything” (The Odyssey, Butler, p.123. Three River Press, 1975. Samuel Butler’s translation of The Odyssey was published in 1900).

Circe and her Swine

Briton Riviere (1840-1920). Circe and Her Swine. Illustration from “Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama Volume I” (originally published 1892 by E. Hess, New York) by Ebenezer Cobham Brewer (1810-1897). “Image from page 434 of “Character sketches of romance, fiction and the drama” (1892)” by Internet Archive Book Images is licensed under CC0 dedication.

Circe Enticing Ulysses

Angelica Kaufman (1741-1807) Circe Enticing Ulysses. 1786. Private Collection. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/ff/Kauffmann_Circe.jpg

Perilous Encounters: The Sirens and Scylla

Notes: The Odyssey (Rendered into English Prose by Samuel Butler first published in 1897), Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1727/1727-h/1727-h.htm

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917). Ulysses and the Sirens. 1891. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. Public Domain.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21997258

After leaving Circe’s island, Ulysses and his crew experience perilous encounters with the Sirens, Scylla, and Charybdis. Circe warns Ulysses of impending peril as he leaves her island. She provides him with suggestions that could save his life. Many of his men on board the ship were not so lucky.

For more information on this story:

The Transformation of Scylla: From Goddess to Sea Monster

Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630), Etching of Glaucus and Scylla. 1606. Illustration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Public Domain. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/400981 or full image, Plate_130-_Scylla_and_Glaucus_(Deus_marinus_effectus_Glaucus_Scyllae_nuptias_ambit),_from_Ovid’s_’Metamorphoses’_MET_DP866535.jpg (1433×1267) (wikimedia.org)

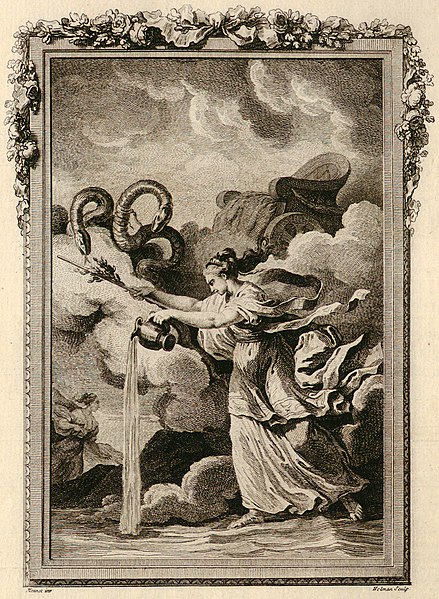

Circe and Scylla

Isidore Stanislas Helman (1743-1806), Circe and Scylla. 1771. Illustration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. 1606. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Ovide_-_Métamorphoses_-_IV_-circé_et_Scylla.jpg (1383×1887) (wikimedia.org)

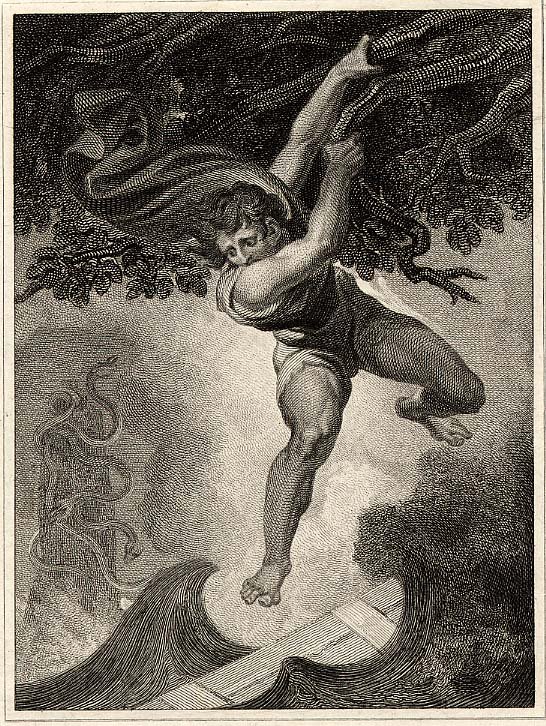

Odysseus Between Scylla and Charybdis

William Bromley (1769–1842). Odysseus Between Scylla and Charybdis. 1806. Etching and engraving after a watercolour by Henry Fuseli (1741-1825). Illustration from the British Museum, Library Pope’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey proof before letters. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Bromley_-_Odysseus_Between_Scylla_and_Charybdis,_1806.jpg

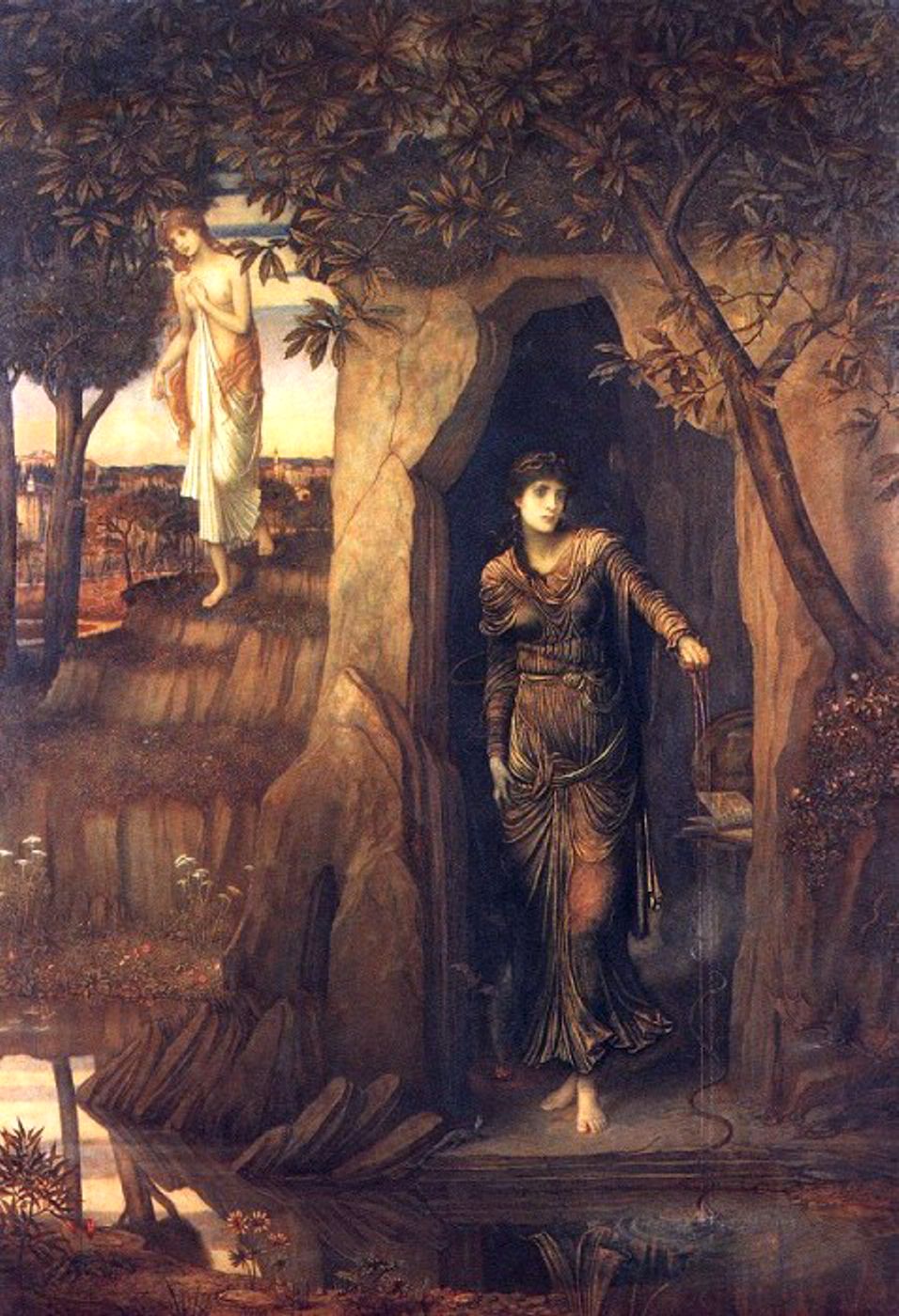

Circe’s Jealousy and Scylla’s Transformation

Scylla was a sea monster who was originally a beautiful maid. Circe the sorceress transforms her into a sea monster with six heads out of jealous. Both goddesses were in love with the prophetic sea god Glaucus. Circe throws a magical potion into the sea when Scylla was bathing. As a result she is transformed into a monster with six dog’s heads ringed around her waist. In this form, she is able to seize ships passing by and devour the crews. Ulysses loses many men to Scylla, Charybdis, and the sirens, but manages to escape and make his way to Calypso’s home on the Maltese island of Gozo.

Circe and Scylla

John Melhuish Strudwick (1849–1937). Circe and Scylla. 1886. Art UK, in Sudley House, Liverpool Museums Trust. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Melhuish_Strudwick22.jpg

For more information on Sudley House, Liverpool:

Circe punishes Glaucus by Turning Scylla into a Monster

Eglon van der Neer (1634-1703), Circe Punishes Glaucus by turning Scylla into a Monster. 1695. Courtesy of Rikjsmusuem. Amsterdam, Netherlands, EU. Public Domain. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-4874

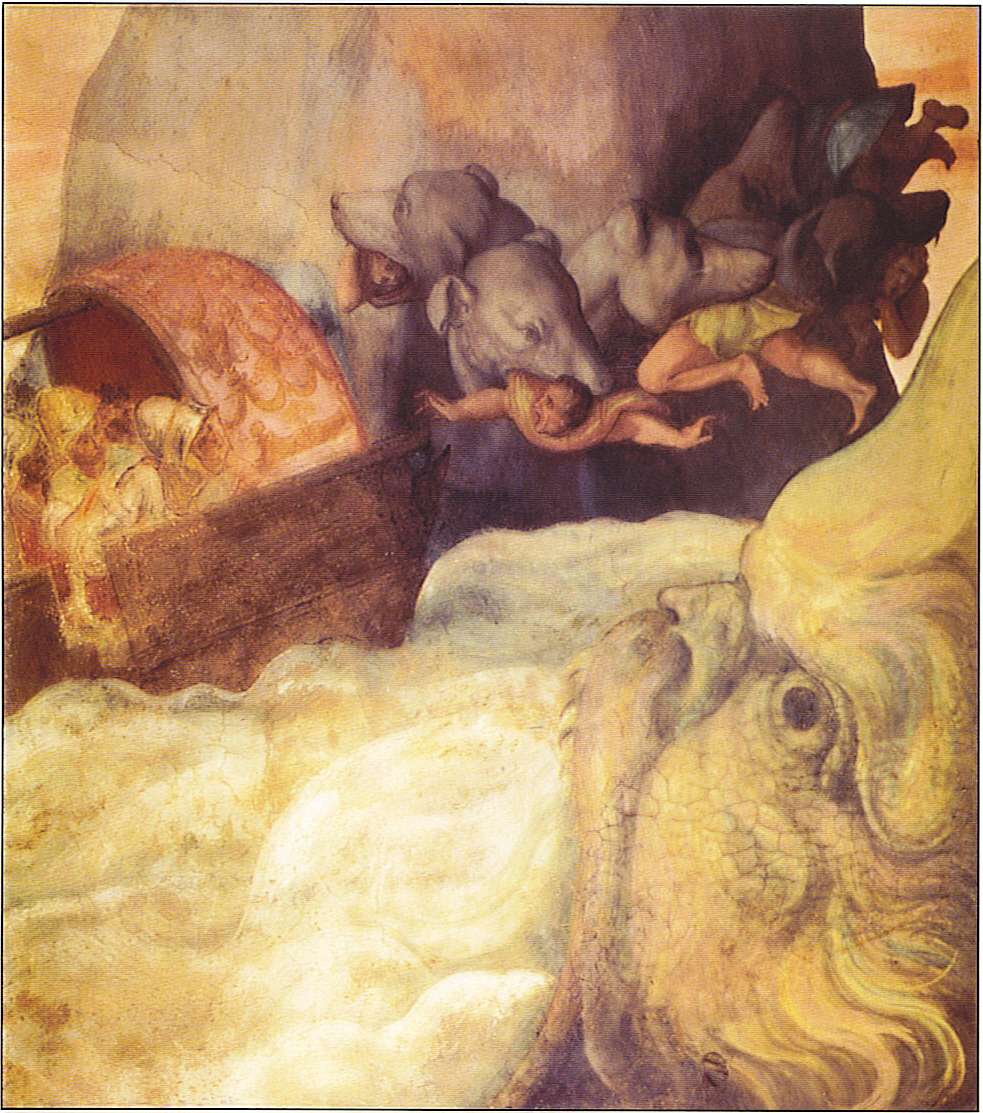

Between a Rock and a Hard Place (Scylla and Charybdis)

Allori’s painting features Odysseus’s boat passing between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis. Scylla has plucked Five of Odysseus’s men from the boat. The painting is an Italian fresco.

Alessandro Allori (1535-1607). Caught Between a Rock and a Hard Place, Italian Fresco, blue pencil sketch. 1575. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Caught_between_a_rock_and_a_hard_place.jpg (983×1113) (wikimedia.org)

The Book of Wonder Voyages (Front Piece)

Joseph Jacob’s Fantastic Creation of Scylla, front-piece illustration. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. The_book_of_wonder_voyages_-_frontispiece.png (1618×2041) (wikimedia.org).

Charbydis and Scylla. Ulysses had to survive the treacherous current of Charbydis and the threat of the monster Scylla. The Strait of Messina near Sicility and Calypso’s island of Malta, the treacherous pair lived. (Ilustration from Philip Sandford, 1900, The Aeneid of Virgil, Blackie & Son, London).

Excerpt from Thomas Bulfinch’s Mythology: The Monster Scylla and the Whirlpool Charybdis

“Ulysses had been warned by Circe of the two monsters Scylla and Charybdis. We have already met with Scylla in the story of Glaucus, and remember that she was once a beautiful maiden and was changed into a snaky monster by Circe. She dwelt in a cave high up on the cliff, from whence she was accustomed to thrust forth her long necks (for she had six heads), and in each of her mouths to seize one of the crew of every vessel passing within reach. The other terror, Charybdis, was a gulf, nearly on a level with the water. Thrice each day the water rushed into a frightful chasm, and thrice was disgorged. Any vessel coming near the whirlpool when the tide was rushing in must inevitably be engulfed; not Neptune himself could save it.

On approaching the haunt of the dread monsters, Ulysses kept strict watch to discover them. The roar of the waters as Charybdis engulfed them, gave warning at a distance, but Scylla could nowhere be discerned. While Ulysses and his men watched with anxious eyes the dreadful whirlpool, they were not equally on their guard from the attack of Scylla, and the monster, darting forth her snaky heads, caught six of his men, and bore them away, shrieking, to her den. It was the saddest sight Ulysses had yet seen; to behold his friends thus sacrificed and hear their cries, unable to afford them any assistance.

Circe had warned him of another danger. After passing Scylla and Charybdis the next land he would make was Thrinakia, an island whereon were pastured the cattle of Hyperion, the Sun, tended by his daughters Lampetia and Phaëthusa. These flocks must not be violated, whatever the wants of the voyagers might be. If this injunction were transgressed destruction was sure to fall on the offenders.

Ulysses would willingly have passed the island of the Sun without stopping, but his companions so urgently pleaded for the rest and refreshment that would be derived from anchoring and passing the night on shore, that Ulysses yielded. He bound them, however, with an oath that they would not touch one of the animals of the sacred flocks and herds, but content themselves with what provision they yet had left of the supply which Circe had put on board. So long as this supply lasted the people kept their oath, but contrary winds detained them at the island for a month, and after consuming all their stock of provisions, they were forced to rely upon the birds and fishes they could catch. Famine pressed them, and at length one day, in the absence of Ulysses, they slew some of the cattle, vainly attempting to make amends for the deed by offering from them a portion to the offended powers. Ulysses, on his return to the shore, was horror-struck at perceiving what they had done, and the more so on account of the portentous signs which followed. The skins crept on the ground, and the joints of meat lowed on the spits while roasting.

The wind becoming fair they sailed from the island. They had not gone far when the weather changed, and a storm of thunder and lightning ensued. A stroke of lightning shattered their mast, which in its fall killed the pilot. At last the vessel itself came to pieces. The keel and mast floating side by side, Ulysses formed of them a raft, to which he clung, and, the wind changing, the waves bore him to Calypso’s island. All the rest of the crew perished.”

” Circe had told Ulysses about the Rocks Wandering, which do not even allow flocks of doves to pass through them; even one of the doves is always caught and crushed, and no ship of men escapes that tries to pass that way, and the bodies of the sailors and the planks of the ships are confusedly tossed by the waves of the sea and the storms of ruinous fire. Of all ships that ever sailed the sea only ‘Argo,’ the ship of Jason, has escaped the Rocks Wandering, as you may read in the story of the Fleece of Gold. For these reasons Ulysses was forced to steer between the rock of the whirlpool and the rock which seemed harmless. In the narrows between these two cliffs the sea ran like a rushing river, and the men, in fear, ceased to hold the oars, and down the stream the oars plashed in confusion. But Ulysses, whom Circe had told of this new danger, bade them grasp the oars again and row hard. He told the man at the helm to steer under the great rocky cliff, on the right, and to keep clear of the whirlpool and the cloud of spray on the left. Well he knew the danger of the rock on the left, for within it was a deep cave, where a monster named Scylla lived, yelping with a shrill voice out of her six hideous heads. Each head hung down from a long, thin, scaly neck, and in each mouth were three rows of greedy teeth, and twelve long feelers, with claws at the ends of them, dropped down, ready to catch at men. There in her cave Scylla sits, fishing with her feelers for dolphins and other great fish, and for men, if any men sail by that way. Against this deadly thing none may fight, for she cannot be slain with the spear.”

Retrieved August 21, 2023 Project Gutenberg eBook of Thomas Bulfinch’s Mythology. Grosset & Dunlap, 1913). https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4928/pg4928.html (Robert Rowe, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team).

Additional Resources:

The Book of Wonder Voyage by Joseph Jacobs:

https://archive.org/details/bookofwondervoya00jacoiala

Map of the ancient world:

https://citizendium.org/wiki/Journey_of_Aeneas

Calypso Declaring Her Love for Ulysses

Angelica Kaufman (1741-1807). Calypso declaring her love for Ulysses (before 1807). Oil on canvas. Unidentified location. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/05/Angelica_Kauffmann_-_Calypso_calling_heaven_and_earth_to_witness_her_sincere_affection_to_Ulysses.jpg

Ulysses before Alcinous, King of the Phaeacians

August Malmström (1829-1901), Ulysses before Alcinous, King of the Phaeacians. 1853. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odysseus_before_Alcinous,_King_of_the_Phaeacians_(August_Malmstr%C3%B6m)_-_Nationalmuseum_-_117888.tif

Port Scene with the Departure of Odysseus from the Land of the Pheacians

Claude Lorraine (1604/05-1682). Port Scene with the Departure of Odysseus from the Land of the Pheacians, 1646. The Louvre Art Museum, Paris, France. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Departure_of_Ulysses_from_the_Land_of_the_Pheacians.jpg

Athena Appearing to Odysseus to Reveal the Island of Ithaca

Giuseppe Bottani (1717-1784), Athena appearing to Odysseus to reveal the Island of Ithaca. Oil on Canvas. Southeby’s Private Collection. Pinacoteca Malaspina, Visconti Castle. Civic Museums, Pavia, Italy. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2a/Athena_appearing_to_Odysseus_to_reveal_the_Island_of_Ithaca_by_Giuseppe_Bottani.jpg

Telemachus on Calypso’s Island

Angelica Kaufman (1741-1807). Telemachus and the Nymphs of Calypso, 1782, Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Public Domain. This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the Image and Data Resources Open Access Policy, licensed under CC0 1.0 attribution. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57670004

Note: Artist Angela Kaufman drew inspiration from the 1699 Tales of Telemachus by Francoise Fenalon. Calypso motions her nymphs to be silent so as not to further upset Telemachus who is searching for his father.

Key Takeaways

Angelica Kauffman drew from François Fénelon’s romance The Adventures of Telemachus in this beautiful painting. In search of his long -lost father Ulysses, Telemachus and Mentor arrive on Calypso’s island where they are greeted by her nymphs.

For more information about the story of Telemachus please open the links below:

Telemachus Meets Calypso

” Telemachus followed the goddess, who was encircled by a crowd of young nymphs, among whom she was distinguished by the superiority of her stature,

as the towering summit of a lofty oak is seen, in the midst of a forest, above all the trees that surround it. Telemachus was struck with the splendour of her beauty,

the rich purple of her long and flowing robe, her hair that was tied with graceful negligence behind her, and the vivacity and softness that were mingled

in her eyes. Mentor followed Telemachus, modestly silent, and looking downward. When they arrived at the entrance of the grotto, Telemachus was surprised to discover, under the appearance of rural simplicity, whatever could captivate the sight. There was, indeed, neither gold, nor silver, nor marble: no decorated columns , no paintings, no statues were to be seen ; but the grotto consisted of several vaults cut in the rock; the roof was embellished with shells and pebbles; and the want of tapestry was supplied by the luxuriance of a young vine, which extended its branches equally on every

side. Here the heat of the sun was tempered by the freshness of the breeze; the rivulets that, with soothing murmurs, wandered through meadows of intermingled violets and amaranth, formed innumerable baths that were pure and transparent as crystal, the verdant carpet which Nature had spread round the grotto, was adorned with a thousand flowers and, at a small distance, there was a wood of those

trees that in every season unfold new blossoms, which diffuse ambrosial fragrance, and ripen into golden fruit. In this wood, which was impervious to the rays of the sun, and heightened the beauty of the adjacent meadows by an agreeable opposition of light and shade, nothing was to be heard but the melody of birds, or the fall of water, which, precipitating from the summit of a rock, was dashed into foam below, where, forming a small rivulet, it glided hastily over the meadow. The grotto of Calypso was situated on the declline of a hill, and commanded a prospect of the sea, sometimes smooth, peaceful, and limpid ; sometimes swelling into mountains, and breaking with idle rage against the shore. At another view a river was dis- covered, in which were many islands surrounded with limes that were covered with flowers, and poplars that raised their heads to the clouds : the streams which formed d those islands seemed to stray through the fields with a kind of sportful wantonness; some rolled along in translucent waves, with a tumultuous rapidity ; some glided away in silence, with a motion that was scarcely perceptible ; and others, after a long circuit, turned back, as if they wished to issue again from their source, and were unwilling to quit the paradise through which they flowed. The distant hills and mountains hid their summits in the blue vapours that hovered over them, and diversified the horizon with cloudy figures that were equally pleasing and romantic. The mountains that were less remote were covered with vines the branches of which were interwoven with each other, and hung down in festoons ; the grapes, which surpassed in luster the richest purple, were too exuberant to be concealed by the foliage, and the branches bowed under the weight of the fruit. The fig, the olive, the pomegranate, and other trees without number, overspread the plain ; so that the whole country had the appearance of a garden or infinite variety and boundless extent.our textbox content here.”

Internet Archive

The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses. Trans. from the French of Salignac de la Mothe-Fenelon (1651-1715) by John Hawkesworth (1715-1773) . Mancherster: Thomas Johnson, Oldham Street, 1798:

For more information about the English writer and editor John Hawksworth (1715-1773) please open the link below:

Telemachus, Searching for his Father Ulysses, Landing on the Isle of Calypso

Richard Westall (1765–1836). Telemachus, searching for his father Ulysses, landing on the isle of Calypso. 1803. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Art UK. Glasgow Museums Resource Centre. Photo credit: Glasgow Life Museums. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND attribution. https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/telemachus-landing-on-the-isle-of-calypso-86715

The Sorrow of Telemachus

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807). The Sorrow of Telemachus (1783). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York, United States.

Courtesy: Bequest of Collis P. Huntington, 1900. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436809 is licensed under CC0 1.0 attribution.

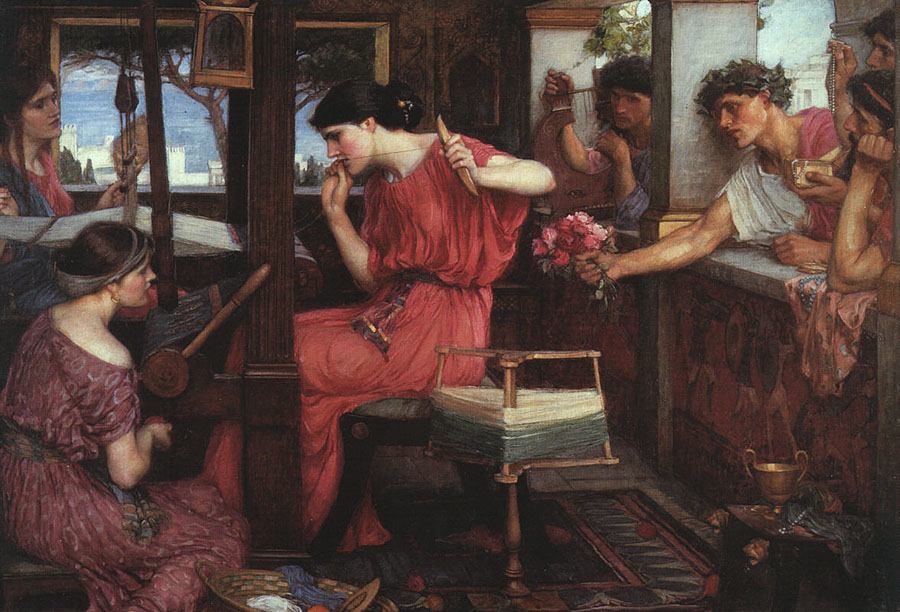

Penelope and Suitors

John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), Penelope and Suitors. 1912. Aberdeen Art Gallery, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bf/JohnWilliamWaterhouse-PenelopeandtheSuitors%281912%29.jpg

Learning Objectives

Revisiting Classic Myths from a Contemporary Lens

Known for her fidelity to Ulysses during his long absence, Penelope rejects the propositions of many suitors. Upon his return, Ulysses kills her suitors. Margaret Atwood revisits the Odyssey from the perspective of Penelope in The Penelopaid. The play is unique in that very different literary styles (ballad, lament, song, rhyming verse, etc.) are used to give voice to the women in The Odyssey. Atwood’s (2005) work formed the first text in the Canongate Myth Series. In this series, classic myths and legends are explored from a 21st century perspective. Gender roles, social stratification, and the socio-cultural meaning of myths are analyzed from a critical and cultural studies lens. Other texts in this series include Karen Armstrong’s (2005) A Short History of Myth, Michel Faber’s (2006) The Fire Gospel, and A.S. Byatt’s (2011) The End of the Gods. These books highlight the value of exploring myths, folktales, and legends from a critical perspective. Who wrote the myths? Whose voices are present? Whose voices are missing and why? What universal truths about human nature are evident in the stories? What can we learn about culture, religion, society, gender roles, psychology, and philosophy from mythic tales? What has changed? What has remained the same? Comparative mythology can also encourage greater transcultural understandings.

For more information on The Canongate series, please open the link below: