33 The Nautilus

The nautilus is a mollusk related to the squid family. It is considered a “living fossil” and its shell has often been thought of as a natural wonder.

“The Shell” by James Stephens

AND then I pressed the shell

Close to my ear

And listened well,

And straightway like a bell

Came low and clear

The slow, sad murmur of the distant seas,

Whipped by an icy breeze

Upon a shore

Wind-swept and desolate.

It was a sunless strand that never bore

The footprint of a man,

Nor felt the weight

Since time began

Of any human quality or stir

Save what the dreary winds and waves incur.

And in the hush of waters was the sound

Of pebbles rolling round,

For ever rolling with a hollow sound.

And bubbling sea-weeds as the waters go

Swish to and fro

Their long, cold tentacles of slimy grey.

There was no day,

Nor ever came a night

Setting the stars alight

To wonder at the moon:

Was twilight only and the frightened croon,

Smitten to whimpers, of the dreary wind

And waves that journeyed blind—

And then I loosed my ear … O, it was sweet

To hear a cart go jolting down the street.

Learning Resources

“Ecosystems in the Ocean,” Biodiversity Heritage Library

“Ocean Life,” Biodiversity Heritage Library

“Ocean: Find Your Blue,” Smithsonian Institution

“The Chambered Nautilus” by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

This is the ship of pearl, which, poets feign,

Sails the unshadowed main,—

The venturous bark that flings

On the sweet summer wind its purpled wings

In gulfs enchanted, where the Siren sings,

And coral reefs lie bare,

Where the cold sea-maids rise to sun their streaming hair.

Its webs of living gauze no more unfurl;

Wrecked is the ship of pearl!

And every chambered cell,

Where its dim dreaming life was wont to dwell,

As the frail tenant shaped his growing shell,

Before thee lies revealed,—

Its irised ceiling rent, its sunless crypt unsealed!

Year after year beheld the silent toil

That spread his lustrous coil;

Still, as the spiral grew,

He left the past year’s dwelling for the new,

Stole with soft step its shining archway through,

Built up its idle door,

Stretched in his last-found home, and knew the old no more.

Thanks for the heavenly message brought by thee,

Child of the wandering sea,

Cast from her lap, forlorn!

From thy dead lips a clearer note is born

Than ever Triton blew from wreathèd horn!

While on mine ear it rings,

Through the deep caves of thought I hear a voice that sings:—

Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea!

The Chambered Nautilus

Excerpt from “The Nautilus: Science and Symbol” by George Gantz (Spiral Inquiry, 2021)

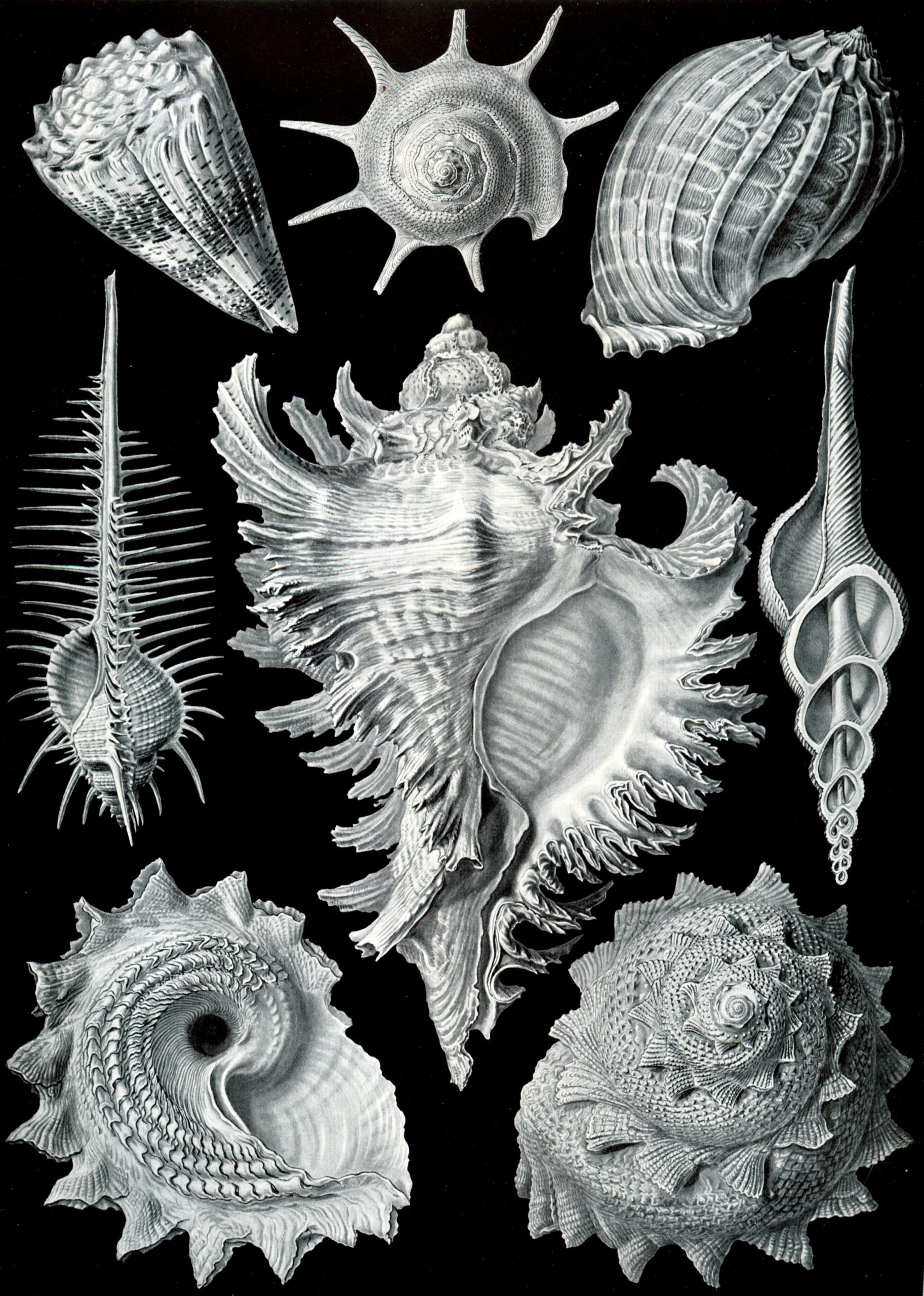

“The chambered nautilus is an ancient species, originating some 500 million years, long before mammals roamed the land and sea, and even well before the dinosaurs. Found only in the remote Pacific, the remarkable shape, color, and rarity made it a prized collector’s specimen in Darwin’s time. It also inspired the name for the first working submarine (c.1800 by Robert Fulton) and the better-known fictional submarine of Jules Verne (1871). It is now on the verge of extinction because of climate change…The remarkable shape of the nautilus is a function of its growth process. As the nautilus organism matures, it builds succeeding chambers, living in the largest and using the former chambers for buoyancy control. The resulting shell is magnificently geometric, in the form of a perfect spiral. The shape is commonly described as a golden spiral, one that follows from the properties of the Fibonacci sequence and the remarkable mathematics of the number phi (φ). The creature and shell are stunningly beautiful.”

Excerpt from The Wonders of Nature by Ben Hoare (2019)

“The word nautilus comes from the ancient Greek for ‘sailor’… You might spot this striped surprise jetting through the ocean. The nautilus (naw-ti-liss) is a distant cousin of octopuses; however, it lives inside a beautiful shell. Poking out are up to 90 spaghetti-like tentacles that the nautilus uses to grab its favourite food: shrimp and crabs. A nautilus uses up energy very slowly, so it only needs to eat once a month. Like a submarine, the nautilus rises and sinks by letting gas and water in and out of chambers in its shell. It moves by squirting seawater from a special tube near it mouth, making it rock gently back and forth. It usually travels backward, shell first, so it can’t see where it’s going” (pp. 152-153).

The Nautilus and Ocean Health and Complexity

In a recent article titled “The Twilight of the Nautilus” in the eponymous Nautilus magazine, writer and researcher Peter Ward describes his personal experience studying the nautilus over the past three decades. His message is clear:

In less than a century, climate change has upended conditions that have sustained life in the Mesophotic Zone for millions of years. Global warming, generated by human activity, has penetrated surface water and caused the water in front of reefs to become lethally warm and anoxic … Although the nautilus doesn’t face as many predators… humans have reduced their numbers…. [but] the buoyant, deep-sea organism with the beautiful spiral shell faces a bigger problem. The water temperature in the ocean layer, defined as the Mesophotic Zone, through which the nautilus travels, is growing so warm that it’s destroying the life of all the organisms that thrive there… The nautilus is the prototypical animal in the Mesophotic Zone. Its survival now foretells the fate of the oceans’ ecological health.

The Stream and Evolution of Life

Excerpt from The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (Oxford University Press, 1989).

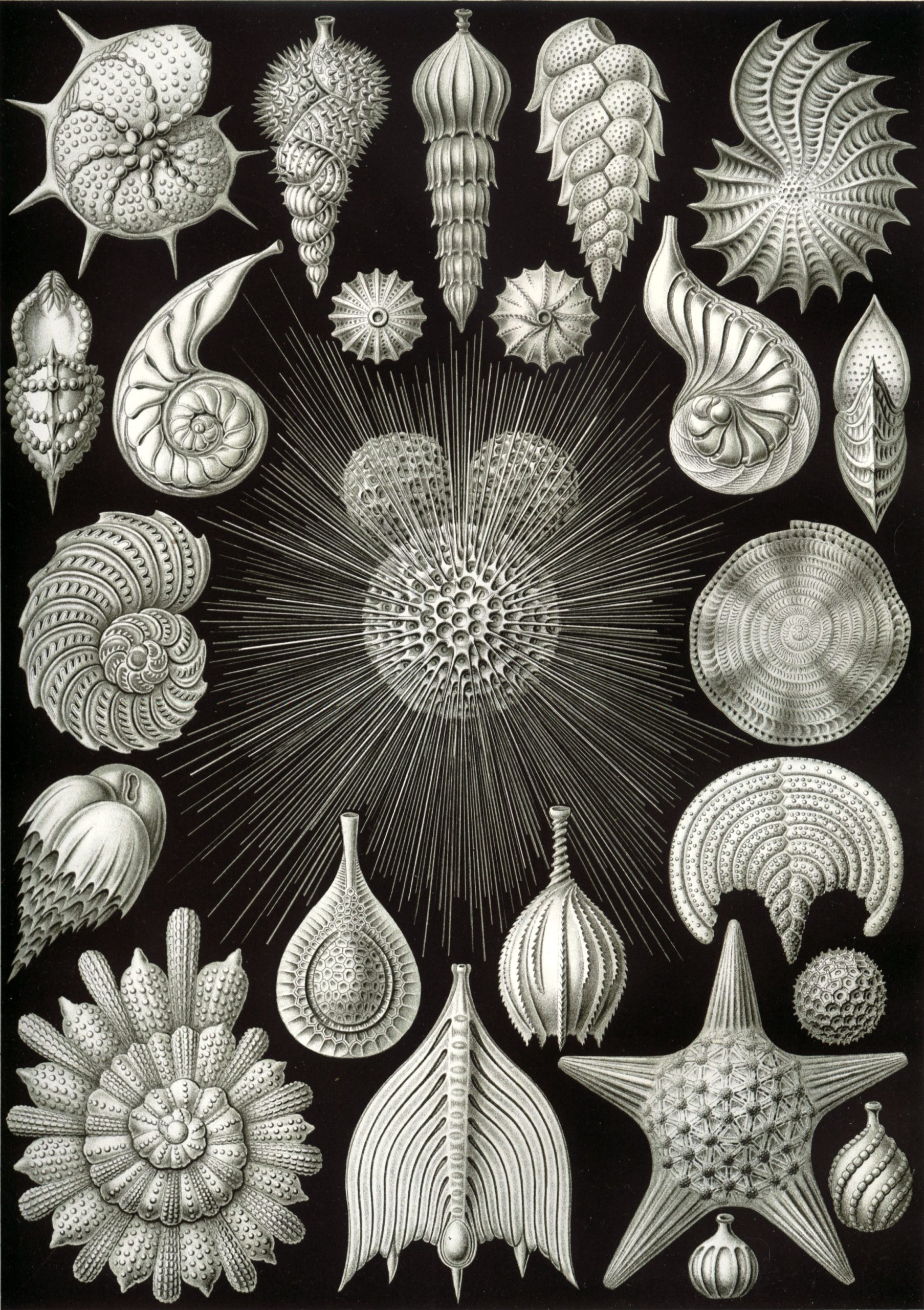

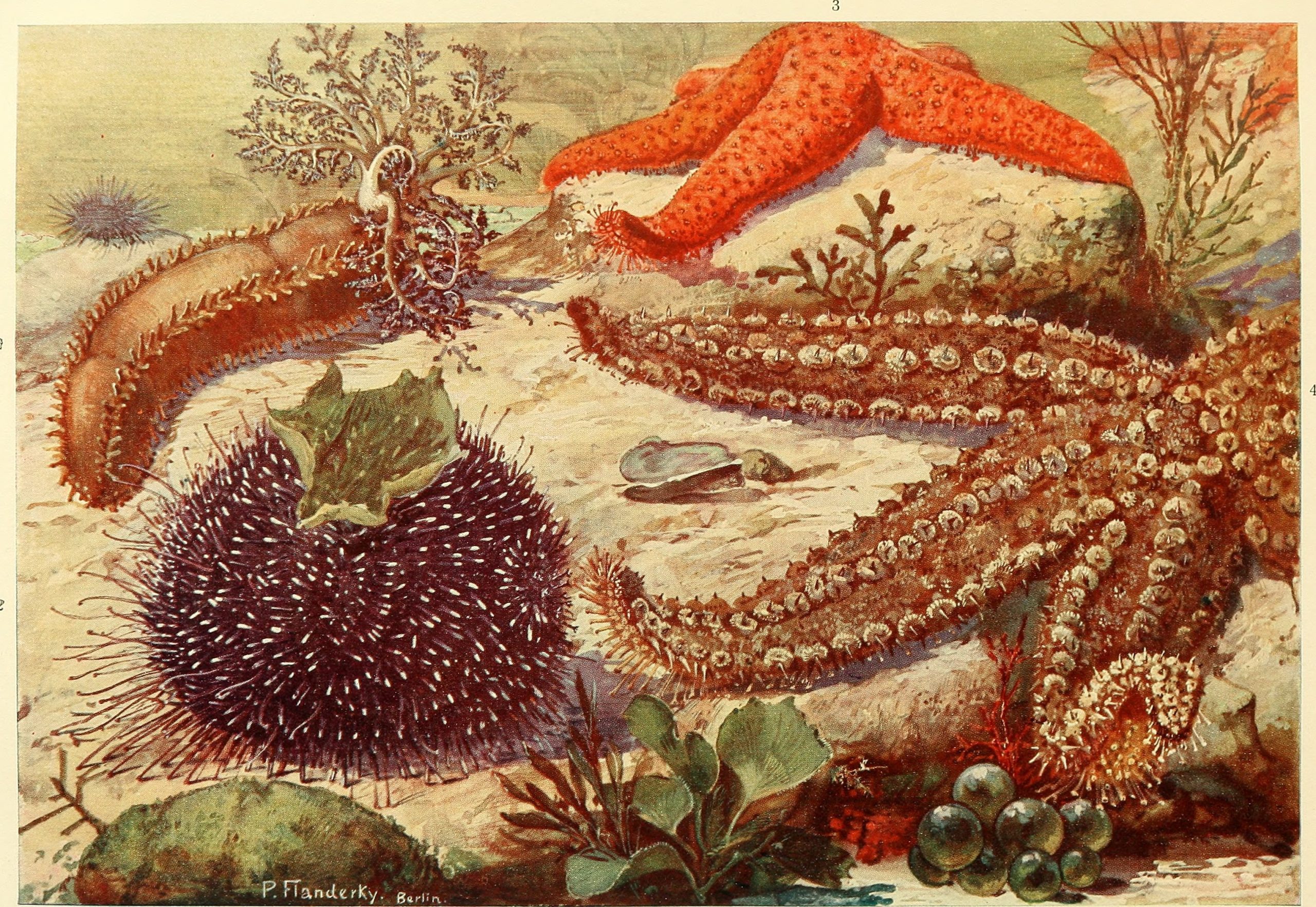

“As the years passed, and the centuries, and the millions of years, the stream of life grew more and more complex. From simple, one-celled creatures, others that were aggregations of specialized cells arose, and then creatures with organs for feeding, digesting, breathing, reproducing. Sponges grew on the rocky bottom of the sea’s edge and coral animals built their habitations in warm, clear waters. Jellyfish swam and drifted in the sea. Worms evolved and star fish, and hard-shelled creatures with many-jointed legs, the arthropods. The plants, too, progressed, from the microscopic algae to branched and curiously fruiting seaweeds that swayed with the tides and were plucked from the coastal rocks by the surf and cast adrift.

During all this time the continents had no life. There was little to induce living things to come ashore, forsaking their all-providing, all-embracing mother sea. The lands must have been bleak and hostile beyond the power of words to describe. Imagine a whole continent of naked rock, across which no covering mantle of green had been drawn—a continent without soil, for there were no land plants to aid in its formation and bind it to the rocks with their roots. Imagine a land of stone, a silent land, except for the sound of the rains and winds that swept across it. For there was no living voice, and no living thing moved over the surface of the rocks.” (pp. 8-9).

Excerpt from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (Pierre-Jules Hetzel, 1870)

“For a quarter of an hour I trod on this sand, sown with the impalpable dust of shells. The hull of the Nautilus, resembling a long shoal, disappeared by degrees; but its lantern, when darkness should overtake us in the waters, would help to guide us on board by its distinct rays.

Soon forms of objects outlined in the distance were discernible. I recognised magnificent rocks, hung with a tapestry of zoophytes of the most beautiful kind, and I was at first struck by the peculiar effect of this medium.

It was then ten in the morning; the rays of the sun struck the surface of the waves at rather an oblique angle, and at the touch of their light, decomposed by refraction as through a prism, flowers, rocks, plants, shells, and polypi were shaded at the edges by the seven solar colours. It was marvellous, a feast for the eyes, this complication of coloured tints, a perfect kaleidoscope of green, yellow, orange, violet, indigo, and blue; in one word, the whole palette of an enthusiastic colourist! Why could I not communicate to Conseil the lively sensations which were mounting to my brain, and rival him in expressions of admiration? For aught I knew, Captain Nemo and his companion might be able to exchange thoughts by means of signs previously agreed upon. So, for want of better, I talked to myself; I declaimed in the copper box which covered my head, thereby expending more air in vain words than was perhaps expedient.

Various kinds of isis, clusters of pure tuft-coral, prickly fungi, and anemones formed a brilliant garden of flowers, enamelled with porphitæ, decked with their collarettes of blue tentacles, sea-stars studding the sandy bottom, together with asterophytons like fine lace embroidered by the hands of naïads, whose festoons were waved by the gentle undulations caused by our walk. It was a real grief to me to crush under my feet the brilliant specimens of molluscs which strewed the ground by thousands, of hammer-heads, donaciae (veritable bounding shells), of staircases, and red helmet-shells, angel-wings, and many others produced by this inexhaustible ocean. But we were bound to walk, so we went on, whilst above our heads waved shoals of physalides leaving their tentacles to float in their train, medusæ whose umbrellas of opal or rose-pink, escalloped with a band of blue, sheltered us from the rays of the sun and fiery pelagiæ, which, in the darkness, would have strewn our path with phosphorescent light.

All these wonders I saw in the space of a quarter of a mile, scarcely stopping, and following Captain Nemo, who beckoned me on by signs. Soon the nature of the soil changed; to the sandy plain succeeded an extent of slimy mud, which the Americans call “ooze,” composed of equal parts of silicious and calcareous shells. We then travelled over a plain of sea-weed of wild and luxuriant vegetation. This sward was of close texture, and soft to the feet, and rivalled the softest carpet woven by the hand of man. But whilst verdure was spread at our feet, it did not abandon our heads. A light network of marine plants, of that inexhaustible family of sea-weeds of which more than two thousand kinds are known, grew on the surface of the water. I saw long ribbons of fucus floating, some globular, others tuberous; laurenciæ and cladostephi of most delicate foliage, and some rhodomeniæ palmatæ, resembling the fan of a cactus. I noticed that the green plants kept nearer the top of the sea, whilst the red were at a greater depth, leaving to the black or brown hydrophytes the care of forming gardens and parterres in the remote beds of the ocean.”