6 Selected Stories and Art Images from Myths

Myths and Meaning

Great artists throughout the centuries depicted classical myths in beautiful paintings, tapestries, sculptures, and other artistic forms. Each of the following mythic stories have meaning beyond the characters’ dilemma. Deeper insights into human nature and motivation can be explored. The expanse of human emotion from joy to despair reflect the human condition today. What life lessons can be learned from each of these mythic characters? Which stories resonate most with you? Excerpts and links to Project Gutenberg ebooks of myths, legends, and folktales (and other resources) can be accessed for further reading and exploration. You can also compare different artists’ rendering of the myths. The vivid detail in the paintings parallel the rich literary descriptions varied authors provide.

Narcissus

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), Narcissus, (1597-1599). Oil on canvas. Located in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome, Italy. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

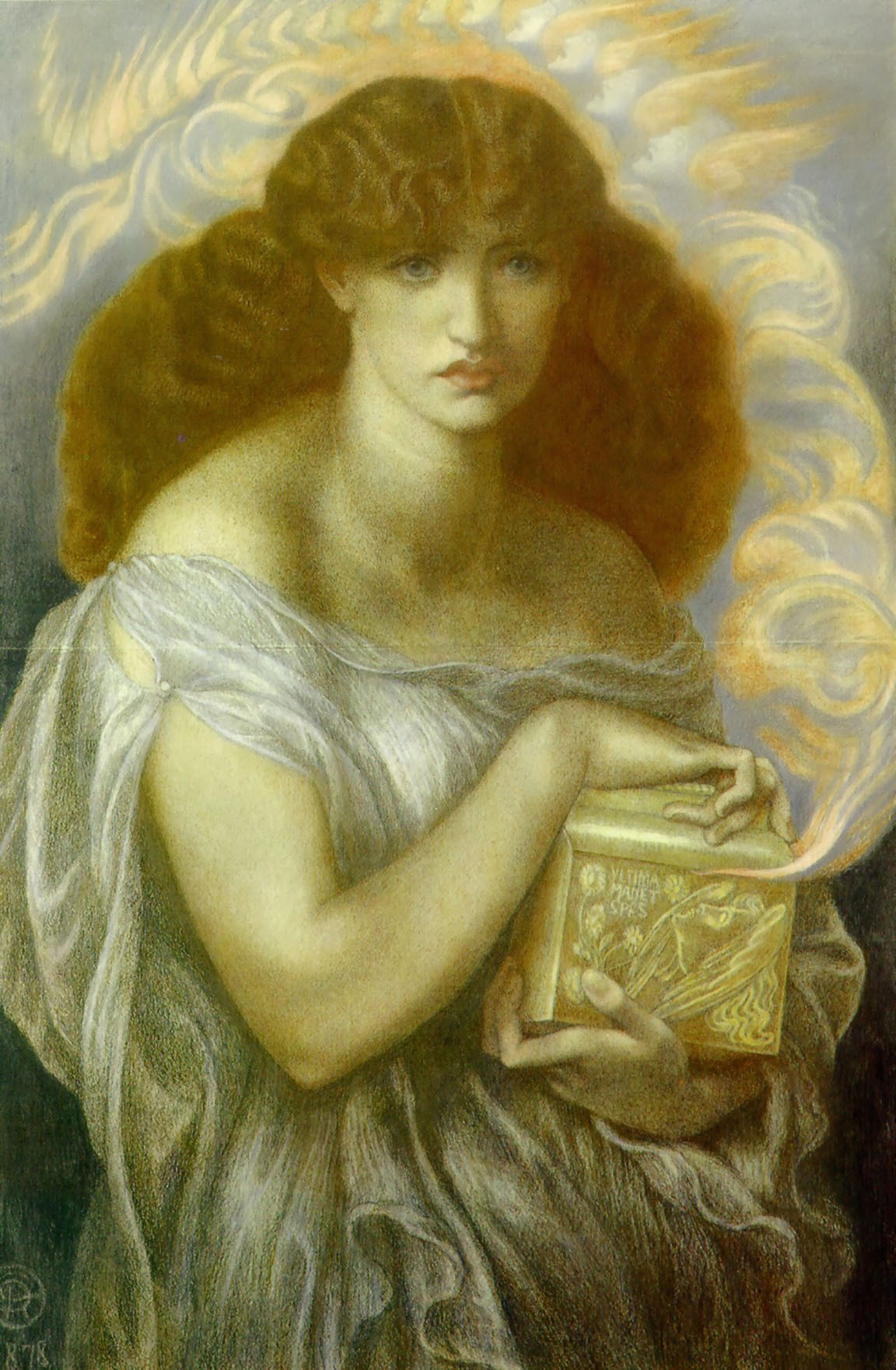

Pandora by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1928-1882), Pandora, Lady Lever Art Gallery, 1879. Liverpool, England. Courtesy of Wikipaintings. Public Domain. http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/dante-gabriel-rossetti/pandora-1879

Pandora

In Greek, the name “Pandora” means all-gifted or all-endowed. According to the Greek myth, Pandora unlocked a box that contained all the “evils of the world” such as poverty, illness, jealousy, and greed. Only hope was left. Poets, dramatists, artists, and sculptors made Pandora their subject and the stories about Pandora have varied throughout the ages.

Excerpt from Thomas Bulfinch’s The golden age of myth and legend (1993, Wordsworth Reference Edition).

“The first woman was named Pandora (All-gifted). She was made in heaven, every god contributing something to perfect her. Venus gave her beauty, Mercury persuasion, Apollo music, etc. Thus equipped, she was conveyed to earth, and presented to Epimetheus, who gladly accepted her, though cautioned his brother to beware of Jupiter and his gifts. Epimetheus had in his house a jar, in which were kept certain noxious articles, for which, in fitting man for his new abode, he had had no occasion. Pandora was seized with an eager curiosity to know what the jar contained; and one day she slipped off the cover and looking in. Forthwith there came a multitude of plagues for hapless man—such as gout, rheumatism, and colic for his body, and envy, spite, and revenge for his mind—and scattered themselves far and wide. Pandora hastened to replace the lid! One thing only excepted, which lay at the bottom, and that was hope. So we see at this day, whatever evils are abroad, hope never entirely leaves us; and while we have that, no amount of other ills can make us completely wretched.” (Excerpt from Thomas Bulfinch’s The golden age of myth and legend, Wordsworth Reference edition, 1993, p. 16).

For more information, please open the link below:

https://www.greeka.com/greece-myths/pandora/

For a re-appraisal of the Greek myths from a post-modern perspective, Haynes retells the stories the stories of Pandora, Medea, Penelope, and other overlooked women in the Greek myths.

For more information, please open the link below:

Excerpt from the myth of Pandora (from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s (1851) The Wonder Book (Illustrated by Walter Crane). Published in 1883/1884 by Houghton Mifflin):

“As Pandora raised the lid, the cottage grew very dark and dismal; for the black cloud had now swept quite over the sun, and seemed to have buried it alive. There had, for a little while past, been a low growling and muttering, which all at once broke into a heavy peal of thunder. But Pandora, heeding nothing of all this, lifted the lid nearly upright, and looked inside. It seemed as if a sudden swarm of winged creatures brushed past her, taking flight out of the box, while, at the same instant, she heard the voice of Epimetheus, with a lamentable tone, as if he were in pain.” (Hawthorne, p.92).

Now, if you wish to know what these ugly things might be, which had made their escape out of the box, I must tell you that they were the whole family of earthly Troubles. There were evil Passions; there were a great many species of Cares; there were more than a hundred and fifty Sorrows; there were Diseases, in a vast number of miserable and painful shapes; there were more kinds of Naughtiness than it would be of any use to talk about. In short, everything that has since afflicted the souls and bodies of mankind had been shut up in the mysterious box,and given to Epimetheus and Pandora to be kept safely, in order that the happy children of the world might never be molested by them. Had they been faithful to their trust, all would have gone well. No grown person would ever have been sad, nor any child have had cause to shed a single tear, from that hour until this moment. (Hawthorne, pp. 92-93)

A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) and Illustrated by Walter Crane (1845-1915).

To read the complete story and others please open the Project Gutenberg ebook of The Wonder Book below:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32242/32242-h/32242-h.htm

For the complete works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, please access the Project Gutenberg link below:

Pandora Opens the Box, an Illustration by Walter Crane

Walter Crane (1845-1915). Pandora Opens the Box. 1982. From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘Wonder Book’ (Illustrated by Walter Crane). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pandora_Opens_The_Box.jpg

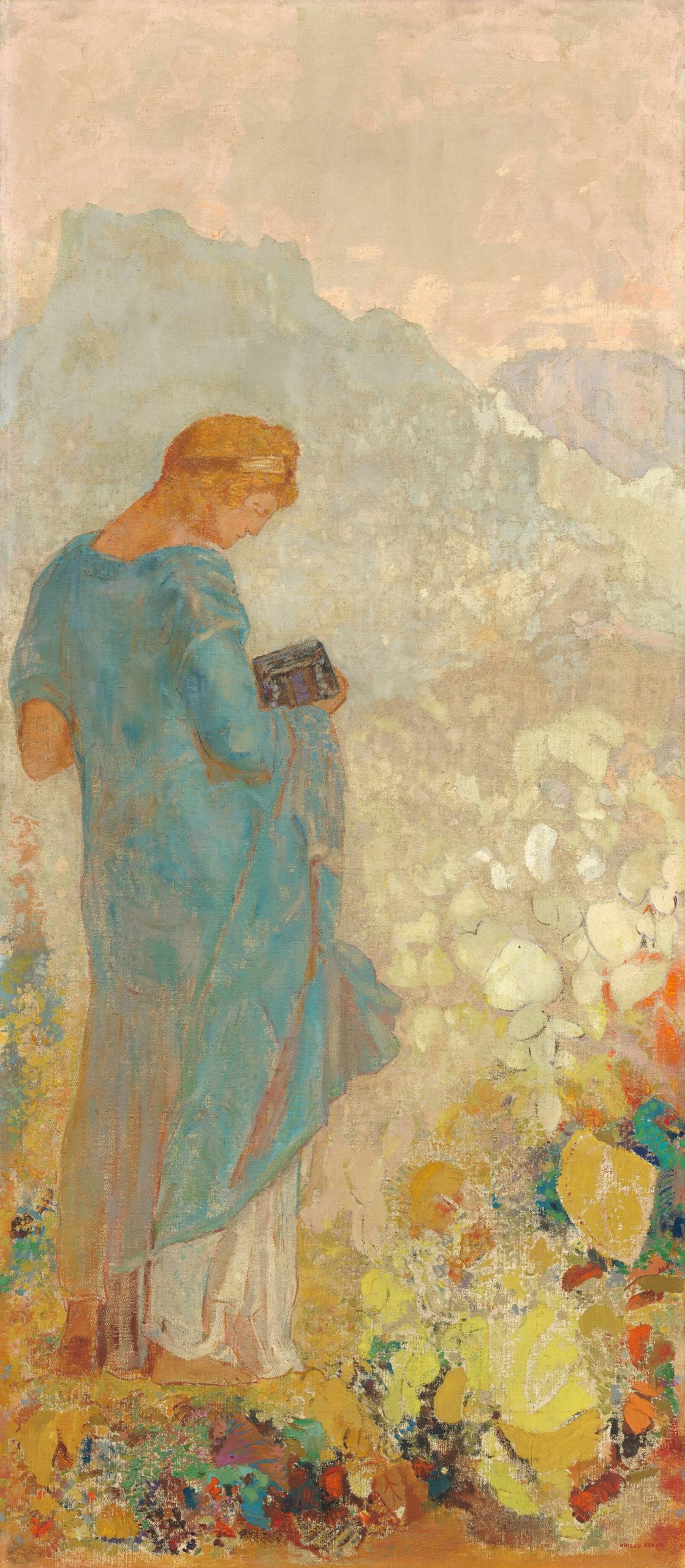

Pandora by Odilon Redon

Odilon Redon (1840-1916) Pandora, 1910/1912. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Open Access Collection. Licensed under CC0 1.0 attribution. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.46531.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus an In Greek mythology, Orpheus was the son of Apollo and the Muse of Calliope. He was a famed Thracian poet and musician; his talents could charm all, including wild animals, trees, and the surrounding landscapes. He is often pictured with his lyre amid a idyllic background of nature. Orpheus was married to Eurydice. After his wife dies tragically from a viper bite, Orpheus is devastated and searches to the underworld to find her. Hades the god of the underworld agrees to return Eurydice on the condition that Orpheus not look back at her as she followed him out of the underworld. Tragically, both Eurydice and Orpheus glimpse back and Eurydice disappears forever into the realm of Hades.

For More information about the Myth of Orpheus, please open the link below:

The Land of the Heroes: Orpheus Leading Eurydice out of Hades

Orpheus and Eurydice (Excerpt from Mary Burt and Zenaide Ragozin Herakles and other Heroes of the Greek Myths, 1900, ) Charles Scribner and Sons.

Orpheus, the Hero of Lyre

“In the same land of Thrace in which Jason’s family ruled, Orpheus, the greatest musician of Greece, was born. It was said that his mother was the Goddess of Song, and such was the power of his voice and his art of playing [79] on the lyre that he could move stones and trees. When the wild beasts heard his music they left their dens and lay down at his feet, the birds in the trees stopped singing, and the fishes came to the surface of the sea to listen to him.

Orpheus had a wife, Eurydike, celebrated for her beauty and virtue, and he loved her very dearly. One day when Eurydike was gathering flowers on the bank of a lake a venomous snake bit her foot and she died. Orpheus could not be consoled. He went off into the wildest waste that he could find and there he mourned day and night till all nature shared in his grief. At last he made up his mind to go down into Hades and beg her back of King Pluto, for life was worthless without her.

Orpheus took his lyre, and singing as he went, found his way down to Hades through a dismal abyss. Grim Cerberus himself held his breath to listen to the marvellous music. Not one bark did he give from any of his three terrible heads, and when Orpheus passed him he crouched at his feet. So Orpheus entered Hades unhindered, and standing before the throne of Pluto and his pale queen Persephone, he said: “Oh, king and queen, I have not come down into Hades to see the gloomy Tartaros nor in order to carry away the three-headed warder of your kingdom, the dreadful Cerberus. I came down to implore you to give me back my beloved wife, Eurydike. I cannot bear life without her. To me the world is a desert, and life a burden. Why should she die, so young and beautiful? Have pity on me! If I may not take her back, then I will not again see the light of the sun, but I, too, will remain in the gloomy Hades.”

To read the complete tale, please access the Project Gutenberg link below:

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/50569/pg50569-images.html

Please refer to the Project Gutenberg ebook link below to read more tales of Herakles:

Art Images of Orpheus and Eurydice

Orpheus Leading Eurydice out of the Underworld

Jean Baptist Camille-Corot (1796-1885), Orpheus Leading Eurydice out of the Underworld, 1861. Museum of Fine Arts. Houston, Texas. https://www.mfah.org/art/detail/11407. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/in

Orpheus Leading Eurydice Out of Hades

Edward Poynter (1836-1919), Orpheus Leading Eurydice Out of Hades, Private Collection. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5d/Edward_Poynter_-_Orpheus_and_Eurydice.jpg

Prose Excerpt from ‘Herakles and other heroes from the Greek Myths’

“Orpheus left Hades in great haste and Eurydice followed him. In the midst of deepest silence they ascended through dismal rocky places. They neared their journey’s end. They could almost see the green earth when Orpheus was seized with a dreadful doubt. “I hear no sound whatever behind me,” he said to himself. “Is my beloved Eurydice really following me?” He turned his head a little. He saw Eurydice, who followed him like a shadow. But suddenly she began to be drawn backward. She stretched out her arms toward Orpheus as if imploring his help. Orpheus hurried to take her in his arms, but she vanished from his sight and Orpheus was alone again.

Yet he did not despair. Again he descended into Hades and reached the river which separates this world from that of the dead, but [82]the boatman, Charon, refused to ferry him across. Seven days and seven nights Orpheus remained there without drink or food, weeping and mourning. The decree of the gods was not to be changed. When Orpheus found that he could effect nothing he returned to the earth. He wandered alone over the mountains and glens of Thrace, which resounded with his plaintive songs day and night.

One day as he sat upon a grassy spot and played his lyre a troop of wild women who were celebrating a festival rushed upon him and tried to make him play for them to dance. Orpheus indignantly refused, and they grew angry and handled him so roughly that he died. Where he was buried the nightingales sang more sweetly than elsewhere. And his lyre, which was thrown into the sea, was caught by the waves, which made sweet music upon it as they rose and fell.

Orpheus was honoured by the gods, and after his death they brought him to the Abode of the Blessed, where he found his beloved Eurydice and was reunited to her.”

Orpheus and Eurydice

Jean Raoux, (1677-1734), Orpheus and Eurydice. 1709. Jean Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles, California, US. Public Domain. http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=720 Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10327439

Eurydice Disappears Back Into Hades

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein-Stub, 1783-1816, Eurydice Disappears Back Into Hades. 1806. Ny Calsberg Gliptotek (The Glyptotek), Oslo, Norway. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15686494

Orpheus (Orphée)

Gustave Moreau (1826-1898) Orpheus (Orphée), 1865, Musee D’Orsay, Paris, France. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Orphée – Gustave Moreau | Musée d’Orsay (musee-orsay.fr)

The Fall of Icarus

Francesco Allegrini (c.1615–after 1679). The Fall of Icarus, Fitzwilliam Museum, The University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England. Art UK. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91872031.

Daedalus and Icarus (Excerpt from Words from the Myths by Isaac Asimov):

“To get away from the island of Crete without being captured by the navy, Daedalus wuld have to escape by air.

Consequently, the clever Daedalus build wings out of bird’s feathers which he attached to a light frame by means of wax. He made a pair for himself and another for [his son] Icarus. Attaching them to their arm, they rose into the air and flew away.

Daedalus had warned Icarus not to fly too high but Icarus, overcome with the joy of lfing and the feeling of power it gave him, could not resist the impulse to show this power by flying higher and higher. (That was hubris). In doing this, Icarus met nemesis at once, for he flew too near the sun. Its heat melted the wax that help the feathers, the wings fell apart, and Icarus tumbled into the section of the sea just off the southwest coast of modern Turkey. This is still called the “Icarian Sea.” ” (Asimov, 1960, p. 93).

Complete Source: Asimov, I. (1961/1969). Words from the myths. Signet/New American Library.

To read more about Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) and his major contributions to Science Fiction, please open the link below:

The Muses

The muses were inspirational goddesses that inspired art, music, science, and literature. There were nine muses and some of the most well-known included: Calliope (the muse of singing and epic poetry); Clio (muse of history); Thailia (muse of comedy and drama); Erato, (the inspirational muse for love poetry), and Urania (the goddess that inspired those who studied astronomy).

Apollo and The Muses

Italian School (Unknown Artist), 1600, Apollo and The Muses, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria, EU. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apollo_and_the_Muses_-_Italian_School_%281600%29.jpg

Neptune, God of the Sea

Werner van den Valckert (1600-1635), Neptune, God of the Sea, 1619. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark, EU. Not provided by the uploader: Shuishouyue. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30269613

The Three Graces

Edouard Bisson (1856-1939), The Three Graces. 1899. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22132846

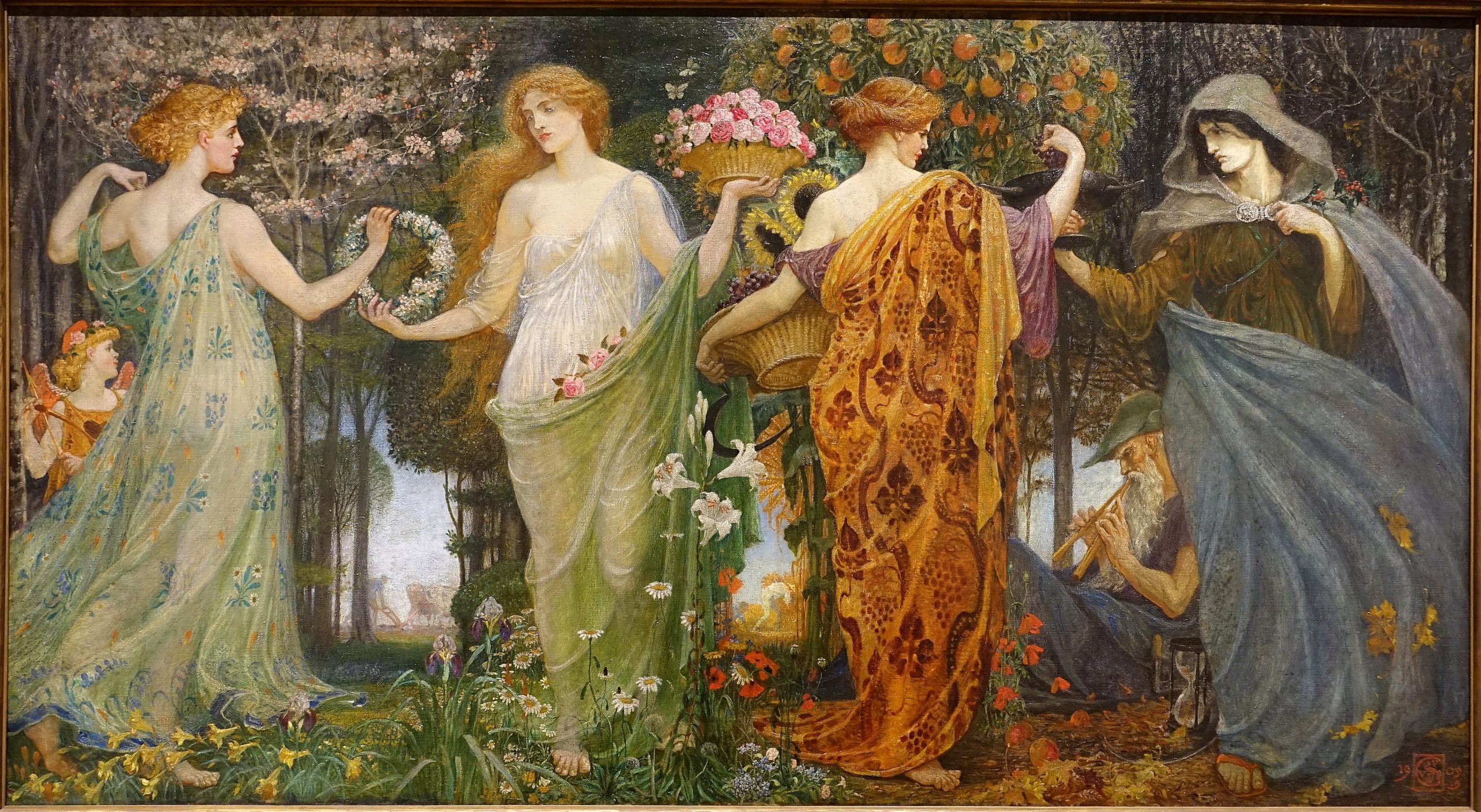

Masque of the Four Seasons

In his painting, Walter Crane depicts the four Greek and Roman Goddesses of the Seasons.

Walter Crane (1845-1915), Masque of the Four Seasons. 1904-1909. Oil on canvas. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. A_Masque_for_the_Four_Seasons,_by_Walter_Crane,_1905-1909,_oil_on_canvas_-_Hessisches_Landesmuseum_Darmstadt_-_Darmstadt,_Germany_-_DSC01240.jpg (5276×2893) (wikimedia.org)

The Muses, Urania and Calliope

Simon Vouet ( -1649). The Muses, Urania and Calliope. 1634. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, United States. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30383667

The Muses Urania and Calliope:

Urania, the Muse of astronomy and astrology, is the youngest of the nine. She is represented in a blue dress with a globe near her on which she measures positions with a compass. In Greek mythology. Calliope is the Muse who presides over eloquence and epic poetry; so called from the ecstatic harmony of her voice. Hesiod and Ovid called her the “Chief of all Muses”.

Faun with a Syrinx

Arnold Bocklin (1827-1901) Faun with a Syrinx. 1875. Neue Pinokotek, Munich, Germany, EU. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/45/Arnold_B%C3%B6cklin_-_Faun%2C_die_Syrinx_blasend_%28ca._1875%29.jpg

Key Takeaways

For more information please follow the link below:

Helen of Troy

Johann Wilhelm Tischbein (1775-1829). Helen of Troy. (painted between 1785-1795). Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cd/Wilhelm_Tischbein_-_Helen_-_2015.322_-_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg

Helen’s face was said to “launch a thousand ships,” and the Trojan war was, in part, blamed on Helen. Paris, the Prince of Troy, abducted Helen, wife of the Spartan King Menelaus, and this began the 10 year Trojan war. “Surely there is no blame on Trojans and strong-greaved Achaians if for a long time they suffer hardship for a woman like this one. Terrible is the likeness of her face to immortal goddesses.”(Book Three, Lines, 156-1538).

Venus Preventing her Son Aeneas by Killing Helen

Luca Ferrari (1605-1664). Venus Preventing her Son Aeneas by Killing Helen. 1650. Art Gallery of South Australia, Melbourne, Australia. Courtesy of Google, Arts & Culture. Public Domain. https://www.agsa.sa.gov.au/collection-publications/collection/works/venus-preventing-her-son-aeneas-from-killing-helen-of-troy/24115/

Helen Brought to Paris

Benjamin West (1738-1820). Helen Brought to Paris. 1776. Smithsonian Art Museum, Washington, DC. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Benjamin_West_-_Helen_Brought_to_Paris_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg (4001×2984) (wikimedia.org)

The Feast of Peleus

Edward Burne Jones (1833-1898). The Feast of Peleus (father of Achilles). 1872. Courtesy of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (Birmingham Museums Trust), Birmingham, UK. Public Domain. http://www.bmagic.org.uk/objects/1956P8. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29237075

Vulcan Hands Thetis the Shield of Achilles

Maarten Van Heemskerck (1498-1574). Vulcan Hands Thetis the Shield of Achilles. 1536. Kunshistoriches Museum, Vienna, Austria. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vulcan_hands_Thetis_the_shield_for_Achilles1536_By_Maerten_van_Heemskerck_born_1498.jpg

From The Illiad:

“Two cities radiant on the shield appear,

The image one of peace, and one of war.

Here sacred pomp and genial feast delight,

And solemn dance, and hymeneal rite;

Along the street the new-made brides are led,

With torches flaming, to the nuptial bed:

The youthful dancers in a circle bound

To the soft flute, and cithern’s silver sound:

Through the fair streets the matrons in a row

Stand in their porches, and enjoy the show….”

Source: The University of California, San Diego: https://poets.org/poem/iliad-book-xviii-shield-achilles

The Shield of Achilles throughout the Ages:

Hephaestus Forging the Shield of Achilles in Art Though the Ages – THE SHIELD OF ACHILLEShttps://theshieldofachilles.net/2018/02/16/hephaestus-forging-shield-of-achilles-art-through-the-ages/

Venus Induces Helen to Fall in Love with Paris

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), Venus Induces Helen to Fall in Love with Paris , 1790, Hermitage Museum, Moscow, Russia. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angelica_Kauffmann_008.jpg

Myths and Legends of All Nations

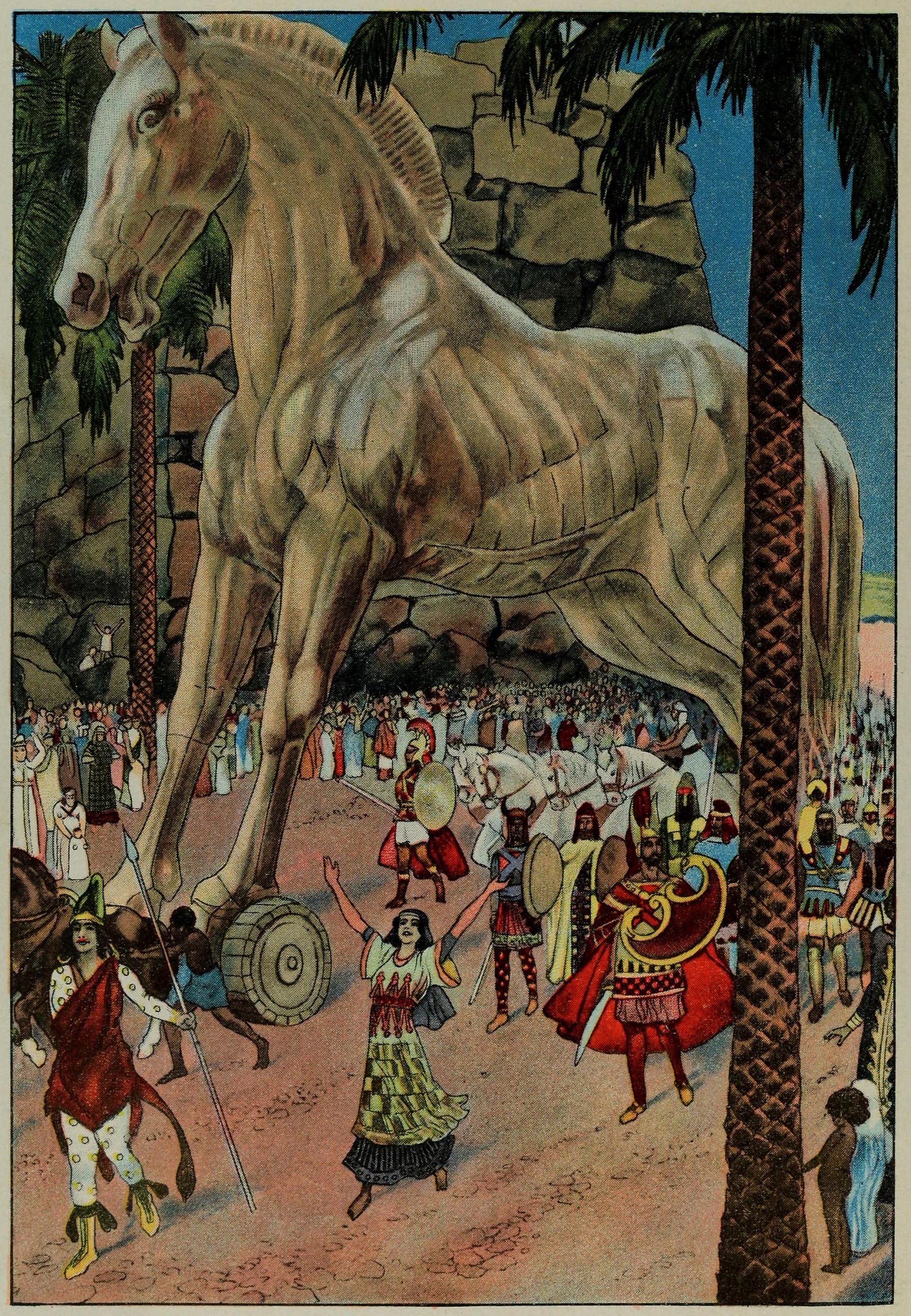

The Trojan Horse

Logan Marshall. The Trojan Horse. 1914. Image was digitized and released to the public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/The_trojan_horse.jpg

The Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was briefly mentioned in the Odyssey (Book IV). Supposedly, the Greeks used the Trojan Horse to win the war and seize Troy. The wooden horse hid the warriors, including Ulysses. The Greeks appeared to sail home in retreat. The Trojans thought that they had won the war and pulled the horse toward their city as a sign of their defeat of the Greeks. At night, the warriors got out of the horse and destroyed the city of Troy, thus ending the war. Ulysses’ adventures and his long journey back home to Ithaca take place after the Trojan war. Aphrodite helps Helen escape from Troy; she returns home and is reunited with her first husband Menelaus.

The Shield of Achilles

Bronze Shield Modelled after Homer’s Iliad by John Flaxman (British, 1755-1826), Manufactured by Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell, London. Photograph of ‘The Shield of Achilles’ by John Flaxman. Courtesy of Thad Zajdowiczm and Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flaxman_shield_of_achilles_cc0_pub_dom_photo_by_Thad_Zajdowicz_flickr_thadz_31680177383_a12794660a_o_resized_to_300_dpi_cropped_tigher_solid_white_background.png

Angelo Monticelli (1778-1837). The Shield of Achilles. 1820. “Le Costume Ancien ou Moderne” (Illustration). Courtesy of Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, DC. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7398764. From the Le Costume ancien et moderne (si.edu) collection.

“The Shield of Achilles” by W.H. Auden, (1907-1973)

1955

The mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes like to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died…

From W.H. Auden, “The Shield of Achilles”

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-shield-of-achilles-by-w-h-auden

In Samuel Butler’s translation of The Iliad, Homer describes the first circles as follows:

”He wrought the earth, the heavens, and the sea; the moon also at her full and the untiring sun, with all the signs that glorify the face of heaven—the Pleiads, the Hyads, huge Orion, and the Bear” (Book XVIII). The next circle of the shield depicts two cities. The first is at peace, showing ”weddings and wedding-feasts” as well as men ”wrangling about the blood-money for a man who had been killed.” The other city is at war, and it depicts two armies ”in gleaming armour, and they were divided whether to sack it, or to spare it and accept the half of what it contained.” (Retrieved from John Butler’s translation of Homer’s The Iliad. Project Gutenberg ebook. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2199/pg2199-images.html).

An Example of Ekphrasis : Homer’s Vivid Description of the Shield of Achilles:

Auden questions the mechanization and brutality of war in his poem. He references Homer’s The Iliad. Achilles’ mother -the sea goddess Thesis—asks Hephaestus (Vulcan) to forge an invincible shield to protect her son in battle. Achilles’ shield includes beautiful representations of peace, work, leisure, and war. Auden re-images the way the shield would look today if the poem were re-written.He explore the ethics and complexities of war. War has become impersonal, mechanized, and destructive. Auden specifically references Book 18 (lines 478-608) from Homer’ s The Iliad in his poem. The detailed imagery is open to numerous interpretations. You can compare the lines in Homer’s epic poem with Auden’s poem and varied artistic depictions of the shield and the mythic characters associated with it.

For Homer’s The Iliad translated by Alexander Pope, please access the Project Gutenberg ebook link below.