35 Birds Connected to Aquatic Environments

“Life depends on water; the sun’s heat evaporates water, often from the sea, and it rises into the atmosphere, forms clouds and is subsequently precipitated once again as rain or snow. Eventually it finds its way back into the sea and so the cycle is repeated. Water that falls on land eventually flows into lakes and rivers and these provide rich habitats for birds” (Perrins and Harrison, 1979, p. 91).

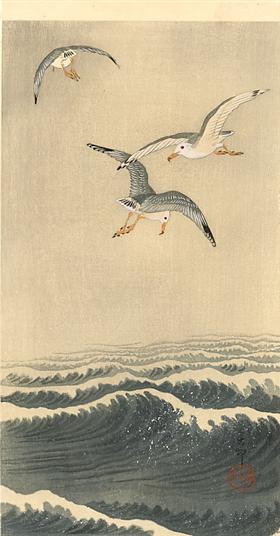

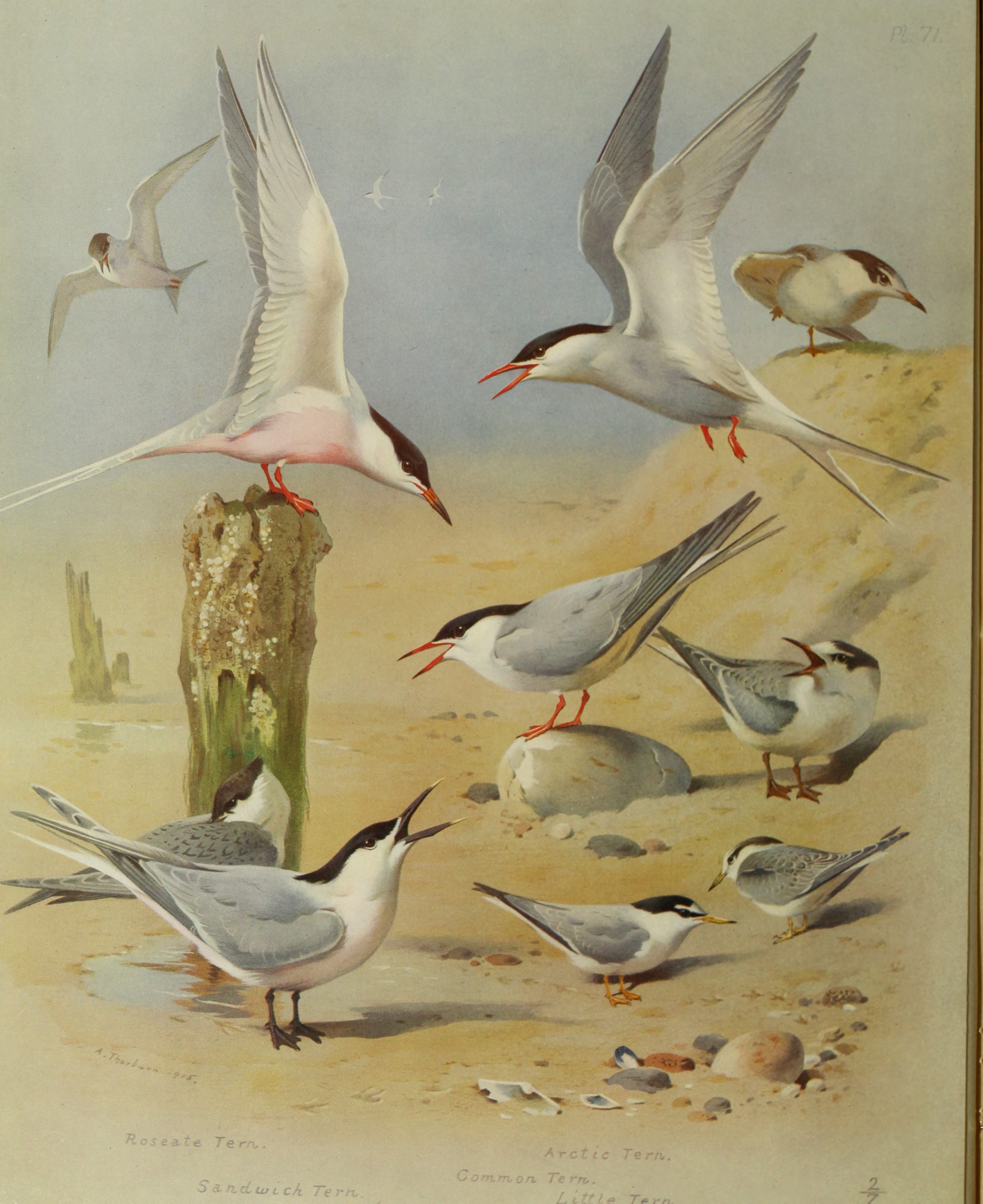

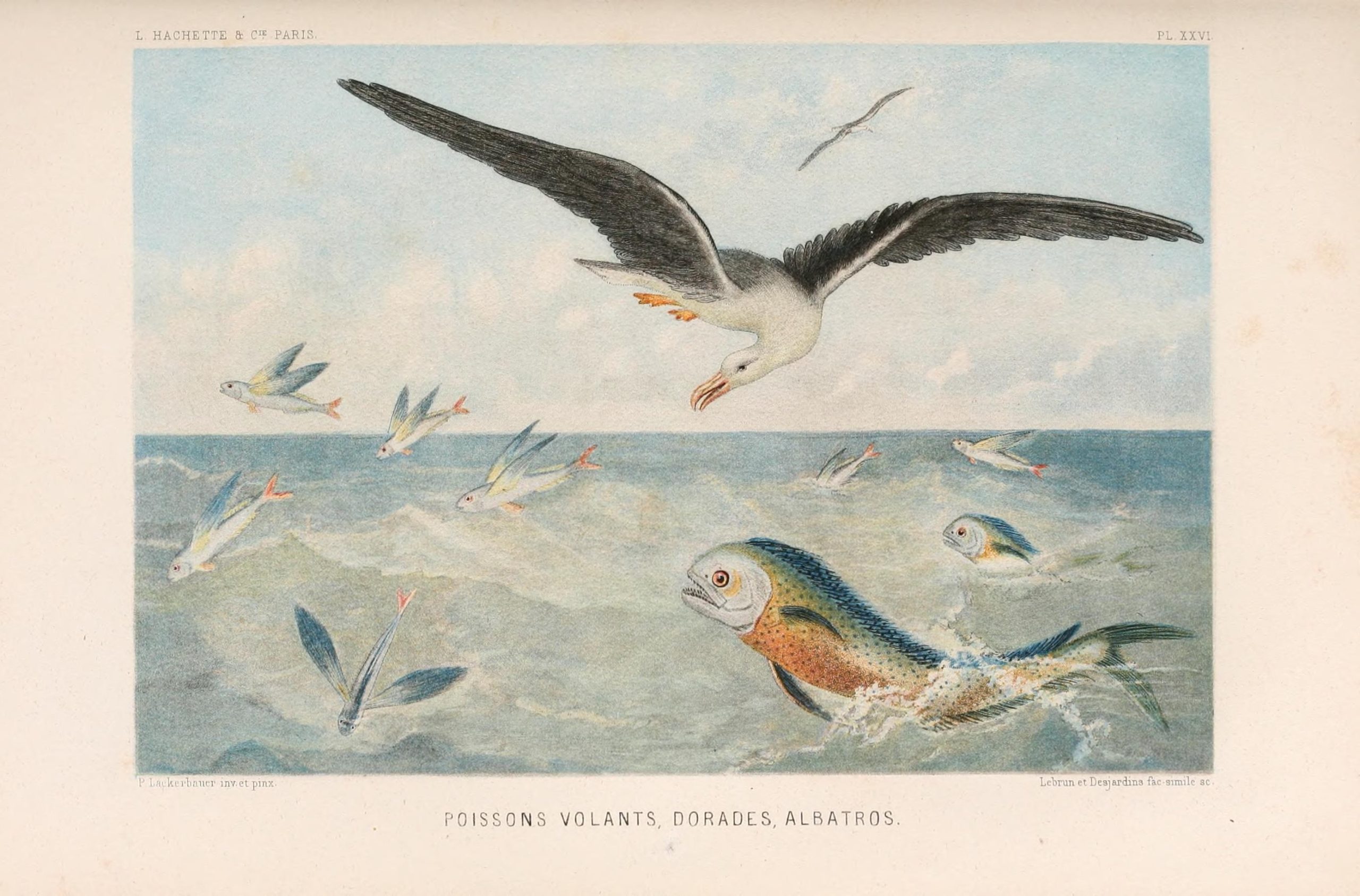

There are many birds that are connected to aquatic environments such as marshes, coastal areas, and other bodies of water; some birds spend long months flying at sea and return to land only to breed. Rich lake and swamp lands are home to birds like herons and cormorants, ducks, gulls, and terns. The marine birds’ habitat has been increasingly threatened due to climate change, severe weather, oil spills, nets, and other forms of habitat destruction. Well-known sea birds include arctic terns, albatross, ducks, pelicans, cormorants, kingfishers, penguins, and puffins. There are also differences in classifications of sea birds; while some birds are connected to marine environments, they are not categorized as sea birds. Conservation efforts such as wildlife refuges for birds and changes to fishing equipment have been established.

“Seabirds generally live longer, breed later and have fewer young than other birds, but they invest a great deal of time in their young. Most species nest in colonies, varying in size from a few dozen birds to millions. Many species are famous for undertaking long annual migrations, crossing the equator or circumnavigating the Earth in some cases. They feed both at the ocean’s surface and below it, and even on each other. Seabirds can be highly pelagic, coastal, or in some cases spend a part of the year away from the sea entirely.” (You can read more about sea birds here.)

The following art images included a few examples birds often connected to marine ecosystems; complementary poems and excerpts from varied texts are also included.

The Arctic Tern: A Remarkable Bird

“A global traveller, the Arctic tern lives in perpetual summer and often in constant daylight. In the long days of the northern summer these terns nest in mostly Arctic latitudes and then ‘winter’ in the Antarctic regions in the southern summer. Arctic terns nest on the ground in large colonies, with three eggs laid in simple scrapes in the vegetation or sand. The parents feed their young on fish caught by diving, wings folded back, headfirst, and, more importantly beak-first, into the waves. This plung-diving method restricts Arctic Terns to feeding on fish shoals within around a metre of the sea surface. The terns gorge on shoals of sand eels, herring, capelin, and sometimes cod” (Avery, 2016, p. 76)

Excerpt from Yeats’ Ireland: An iIlustrated Anthology by Benedict Kiely (Aurum Press, 1989)

“Light as a sylph, the Arctic Tern dances through the air above and around you. The graces, one might imagine, had taught it to perform those beautiful gambols which you see it display the moment you approach the spot which it has chosen for its nest. Over many a league of ocean has it passed, regardless of the dangers and difficulties that might deter a more considerate traveller. Now over some solitary green isle, a creek or an extensive bay, it sweeps, now over the expanse of the boundless sea; at length it has reached the distant regions of the north, and amidst the floating icebergs stoops to pick up a shrimp. It betakes itself to the borders of a lonely sand-bank, or a low rocky island; there side by side the males and the females alight, and congratulate each other on the happy termination of their long journey. Little care is required to form a cradle for their progeny; in a short time the variegated eggs are deposited, the little Terns soon burst the shell, and in a few days hobble towards the edge of the water, as if to save their fond parents trouble; feathers now sprout on their wings, and gradually invest their whole body; the young birds at length rise on wing, and follow their friends to sea. But now the brief summer of the north is ended, dark clouds obscure the sun, a snow-storm advances from the polar lands, and before it skim the buoyant Terns, rejoicing at the prospect of returning to the southern regions” (p. 14).

To read more about arctic terns please open the link here

To read more about marine ecosystems please open the link here.

“The Eagle” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ring’d with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

“The Wild Swans at Coole” by William Butler Yeats

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine and fifty swans.

The nineteenth Autumn has come upon me

Since I first made my count;

I saw, before I had well finished,

All suddenly mount

And scatter wheeling in great broken rings

Upon their clamorous wings.

I have looked upon those brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold,

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes, when I awake.

“Ballad to a Kingfisher” by Sir Charles G.D. Roberts

Kingfisher, whence cometh it

That you perch here, collected and fine,

On a dead willow alit

Instead of a sea-watching pine?

Are you content to resign

The windy, tall cliffs, and the fret

Of the rocks in the free-smelling brine?

O, Kingfisher, do you forget?

Here do you chatter and flit

Where bowering branches entwine,

Of Ceyx not mindful a whit,

And that terrible anguish of thine?

Can it be that you never repine?

Aren’t you Alcyone yet?

Eager only on minnows to dine,

O Kingfisher, how you forget!

To yon hole in the bank is it fit

That your bone-woven nest you consign,

And the ship-wrecking tempests permit

For lack of your presence benign?

With your name for a pledge and a sign

Of seas calmed and storms assuaged set

By John Milton, the vast, the divine,

O Kingfisher, still you forget.

ENVOI

But here’s a reminder of mine,

And perhaps the last you will get;

So, what’s due your illustrious line

Now, Kingfisher, do not forget.

You can read more poems by leading Canadian poet and animal storywriter Charles G.D. Roberts here.

“The Kingfisher” by Maurice Thompson

He laughs by the summer stream

Where the lilies nod and dream,

As through the sheen of water cool and clear

He sees the chub and sunfish cutting sheer.

His are resplendent eyes;

His mien is kingliwise;

And down the May wind rides he like a king,

With more than royal purple on his wing.

His palace is the brake

Where the rushes shine and shake;

His music is the murmur of the stream,

And that leaf-rustle where the lilies dream.

Such life as his would be

A more than heaven to me:

All sun, all bloom, all happy weather,

All joys bound in a sheaf together.

No wonder he laughs so loud!

No wonder he looks so proud!

There are great kings would give their royalty

To have one day of his felicity!

You can find the complete works of Maurice Thompson at Project Gutenberg here.

“The White Birds” by William Butler Yeats

I would that we were, my beloved, white birds on the

foam of the sea!

We tire of the flame of the meteor, before it can fade

and flee;

And the flame of the blue star of twilight, hung low

on the rim of the sky,

Has awaken in our hearts, my beloved, a sadness that

may not die.

A weariness comes from those dreamers, dew-dabbled,

the lily and rose;

Ah, dream not of them, my beloved, the flame of the

meteor that goes,

Or the flame of the blue star that lingers hung low in

the fall of the dew:

For I would we were changed to white birds on the

wandering foam: I and you!

I am haunted by numberless islands, and many a

Danaan shore,

Where Time would surely forget us, and Sorrow come

near us no more;

Soon far from the rose and the lily and fret of the

flames would we be,

Were we only white birds, my beloved, buoyed out on

the foam of the sea!

For more examples of the illustrations from Birds of America by John James Audubon please see the links below:

Birds of America (Illustrations)

Synopsis of the Birds of North America

Excerpt from Birds of America by John James Audubon (1827)

“I feel great pleasure, good reader, in assuring you, that our White Pelican, which has hitherto been considered the same as that found in Europe, is quite different. In consequence of this discovery, I have honoured it with the name of my beloved country, over the mighty streams of which, may this splendid bird wander free and unmolested to the most distant times, as it has already done from the misty ages of unknown antiquity.

In Dr. Richardson’s introduction to the second volume of the Fauna Boreali-Americana, we are informed, that the Pelecanus Onocrotalus (which is the bird now named P. Americanus) flies in dense flocks all the summer in the Fur Countries. At page 472, the same intrepid traveller says, that “Pelicans are numerous in the interior of the Fur Countries up to the sixty-first parallel; but they seldom come within two hundred miles of Hudson’s Bay. They deposit their eggs usually on rocky islands, on the brink of cascades, where they can scarcely be approached; but they are otherwise by no means shy birds.” My learned friend also speaks of the “long thin bony process seen on the upper mandible of the bill of this species;” and although neither he nor Mr. SWAINSON pointed out the actual differences otherwise existing between this and the European species, he states that no such appearance has been described as occurring on the bills of the White Pelicans of the old Continent.”

You can read a biography of John James Audubon from the National Gallery of Art here.

“There Was Once a Puffin” by Florence Page Jaques

Oh, there once was a Puffin

Just the shape of a muffin,

And he lived on an island

In the bright blue sea!

He ate little fishes,

That were most delicious,

And he had them for supper

And he had them for tea.

But this poor little Puffin,

He couldn’t play nothin’,

For he hadn’t anybody

To play with at all.

So he sat on his island,

And he cried for awhile, and

He felt very lonely,

And he felt very small.

Then along came the fishes,

And they said, “If you wishes,

You can have us for playmates,

Instead of for tea!”

So they now play together,

In all sorts of weather,

And the Puffin eats pancakes,

Like you and like me.

You can read more about Florence Page Jaques here.

Excerpt from A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf by John Muir (Houghton Mifflin and Co., 1916).

“‘John Muir-Earth-Planet, Universe.’ – These words are written on the inside cover of the notebook from which the contents of this volume have been taken. They reflect the mood in which the late author and explorer undertook his thousand-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico a half-century ago. No less does this refreshingly cosmopolitan address, which might have startled any finder of the book, reveal the temper and the comprehensiveness of Mr. Muir’s mind. He never was and never could be a parochial student of nature. Even at the early age of twenty-nine his eager interest in every aspect of the natural world had made him a citizen of the universe.”

Further Resources

“The Bird Tragedy on Laysan Island” by William T. Hornaday (Library of America, 2017)

The Journals of Henry David Thoreau

“Ecopsychology in Canada” by Carol A. Koziol

“The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis” by Lynn White

Excerpt from The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (Oxford University Press, 1989)

“A sea from which birds travel not within a year, so vast it is and fearful.” – Homer

“To the ancient Greeks the ocean was a n endless stream that that flowed forever around the border of the world, ceaselessly turning upon itself like a wheel, the end of earth, the beginning of heaven. The ocean was boundless; it was infinite. If a person were to venture far out upon it—were such a course thinkable—he would pass through gathering darkness and obscuring fog and would come at last to a dreadful and chaotic blending of sea and sky, a place where whirlpools and yawning abysses wanted to draw the traveler down into a dark world from which there was no return.

These ideas are found, in varying form, in much of the literature of the ten centuries before the Christian era, and in later years they keep recurring even through the greater part of the Middle Ages. To the Greeks the familiar Mediterranean was The Sea. Outside, bathing the periphery of the land world, was Oceanus. Perhaps somewhere in its uttermost expanse was the home of the gods and of departed spirits, the Elysian fields. SO we meet the ideas of unattainable continents or of beautiful islands in the distant ocean, confusedly mingled with references to a bottomless gulf at the edge of the world—but always around the disc of the habitable world was the vast ocean, encircling all” (pp. 199–200).