12 Out of the Depths: Sea Monsters and Other Fantastical Images

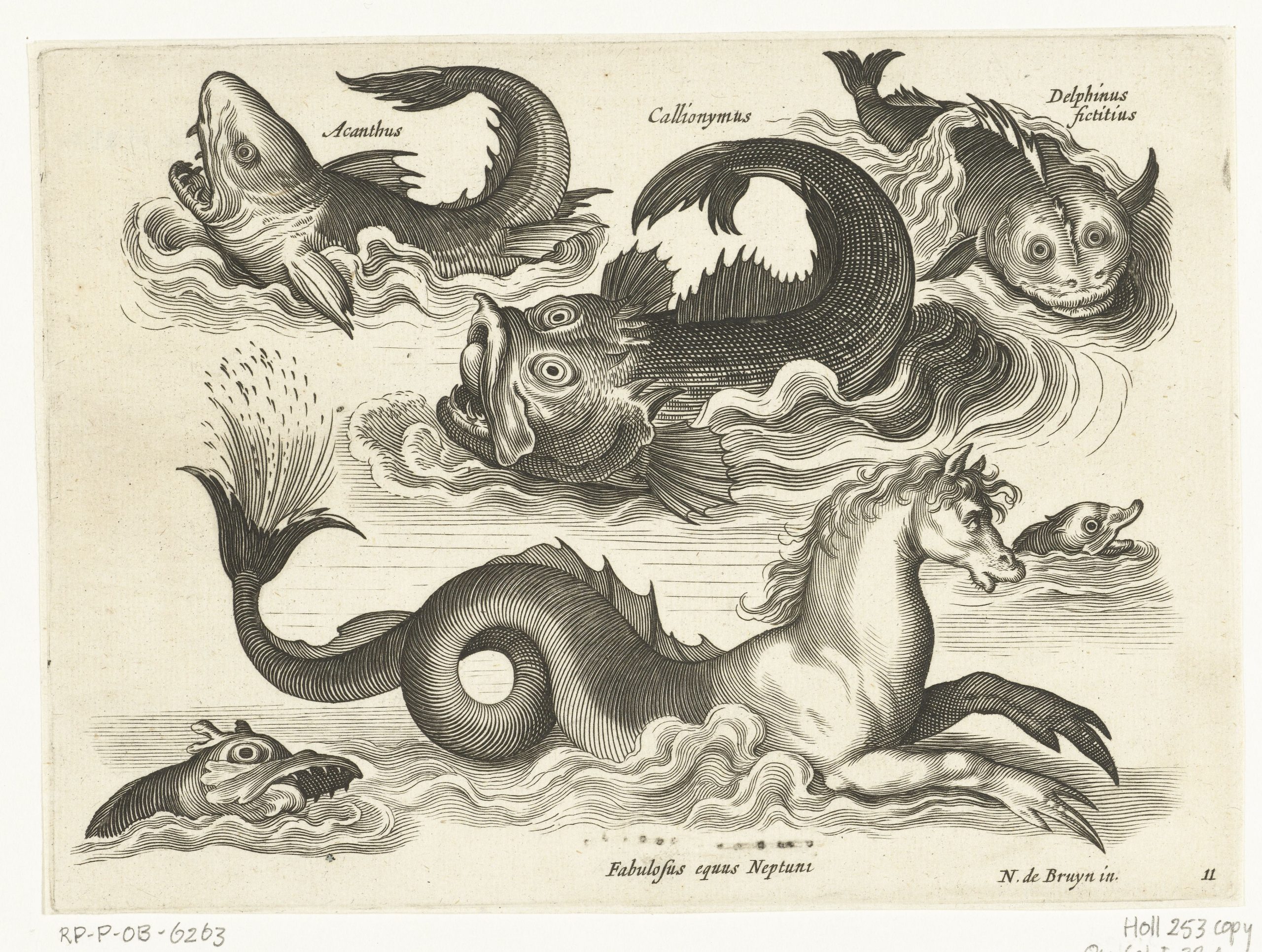

Conrad Gessner and Sebastian Münster: Renaissance Polymaths

Renaissance polymaths such as the German writer and illustrator Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) had a fascination with natural history, philosophy, botany, medicine, geography, zoology, and the natural world. Gessner’s pioneering work created a bridge and transition between ancient, medieval, and modern science. Gessner was a physician, philosopher, encyclopaedist, bibliographer, philologist, natural historian and illustrator. Through his extensive travels, he described the fascinating animals he saw. His travels were organized and comprehensively detailed to include vivid descriptions of diverse species of animals. Books such as Bbiliotheca universalis (1545-1549) and Historia animalium (1551-1558) included extensive details based on accurate accounts of varied animal species. Gessner also drew upon the Old Testament, world legends, myths, and folk lore to illustrate fabulous monsters and mythic creatures. (Adapted from Wikipedia).

Sebastian Münster (1488–1552), a German cartographer, cosmographer and Hebraic scholar, was one of the more influential minds of his time. His elaborate imaginings of sea monsters were based upon myths, folk tales, and perilous descriptions by men of the sea life they encountered on voyages near home and further abroad. Referred to as “Munster’s Monsters” Sebastian Munster’s bestiary of sea serpents and creatures (some real while some imagined) were included in the 1545 Cosmographia. Most of the beasts here are derived from a 1539 map of Scandinavia drawn by Olaus Magnus (Adapted from Wikipedia).

The Cosmographia (Wikipedia)

“The Cosmographia had numerous editions in different languages including Latin, French (translated by François de Belleforest), Italian and Czech. Only extracts have been translated into English. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Munster’s death. The Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century. It passed through 24 editions in 100 years. This success was due to the notable woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). It was most important in reviving geography in 16th-century Europe. Among the notable maps within Cosmographia is the map ‘Tabula novarum insularum,’ which is credited as the first map to show the American continents as geographically discrete.”

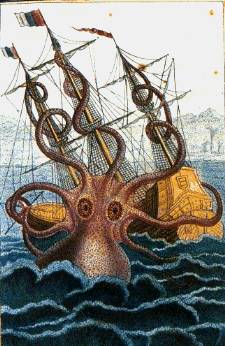

Sebastian Münster’s “kraken octopus” described the very real giant squid, Architeuthis, proven to exist in 1857. Kendell, Norell, and Ellis (2016) explain that the kraken or sea monster (thought to be capable of destroying a small ship) was imagined from the tentacles of a giant squid. These non-aggressive creatures that lived in great ocean depths were rarely seen. “Many sea monsters include feature of living animals. A large tentacle becomes part of a monstrous sea serpent or a many-armed kraken — the eye sees a fragment, the mind fills in the rest. A blend of tall tales, mistaken identity, and resonant cultural symbols, stories of sea monsters often reveal more about the minds of imaginers than they do about the natural world” (Kendell, Norell, and Ellis, 2016, p. 9).

Pierre Dénys de Montfort was a French naturalist, in particular a malacologist, remembered today for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of the gigantic octopuses. He was inspired by a description from 1783 of an eight-metre long tentacle found in the mouth of a sperm whale. Below is a pen and wash drawing by Dénys de Montfort from the descriptions of French sailors reportedly attacked by such a creature off the coast of Angola. The scene features a ship being ensnared and damaged by a “colossal octopus” but relabeled as a kraken here in the engraving in Robert Hamilton MD’s book. Sepia in former usage included octopi and not just cuttlefish.

“The Kraken” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides: above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant fins the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages and will lie

Battering upon huge seaworms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by men and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

You can find more collected works by Alfred Lord Tennyson here.

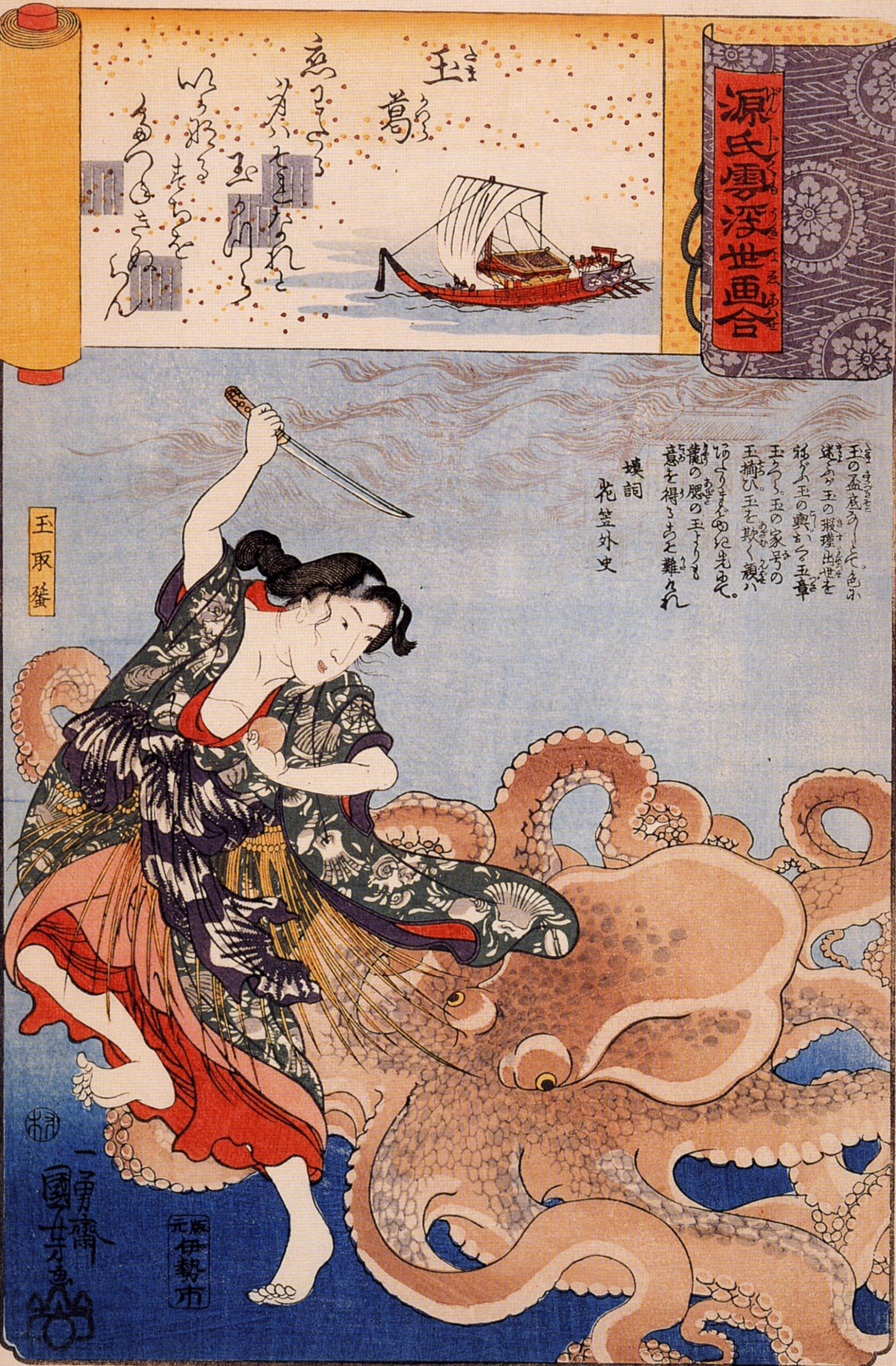

Princess Tamatora has recovered the pearl from the palace on the Dragon king, while she was threatened by all sea creatures.

For more folk tales from Japan, you can find Japanese Fairy Tales compiled by Yei Theodora Ozaki (1908) here.

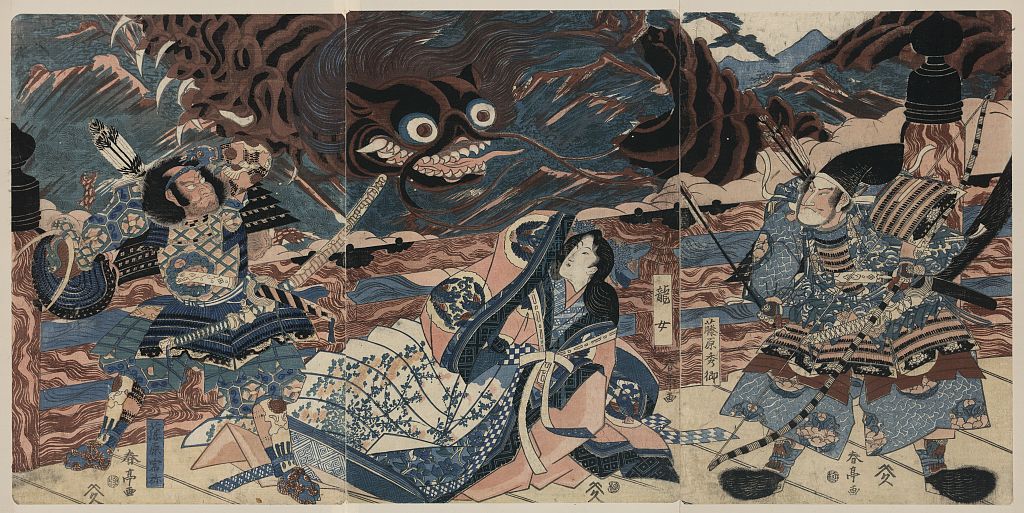

Excerpt from “Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Tenjin Shrine” (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“In the Shinto religion, there is the belief that human spirits that are suffering can activate forces of nature. This theme informs the origins of Kyoto’s Kitano Tenjin Shrine (Kitano Tenmangu). This mural is dedicated to the stateman and scholar-poet Sugawara no Michizane (845-903). After his shunning and exile, a series of natural disasters and plagues impacted Kyoto. Michizane’s spirit was appeased when a shrine was built to honour the Shinto god of literature and music.”

Excerpt from “Shinto” by Department of Asian Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“The ancient Japanese found divinity manifested within nature itself. Flowering peaks, flowing rivers, and venerable trees, for example, were thought to be sanctified by the deities, or kami, that inhabited them. This indigenous “Way of the Gods,” or Shinto, can be understood as a multifaceted assembly of practices, attitudes, and institutions that express the Japanese people’s relationship with their land and the lifecycles of the earth and humans. Shinto emerged gradually in ancient times and is distinctive in that it has no founder, no sacred books, no teachers, no saints, and no well-defined pantheon. It never developed a moral order or a hierarchical priesthood and did not offer salvation after death. The oldest type of Shinto ceremonies that could be called religious were dedicated to agriculture and always emphasized ritual purity. Worship took place outdoors at sites proclaimed to be sacred. In time, however, the ancient Japanese built permanent structures to honor their gods. Shrines were usually built on mountains or in rural areas, often on unlevel ground, without any symmetrical plan.”

Further Resources

“82 Questions to Ask About Art” by Cindy Ingram (Art Class Curator)

“Albertus Seba’s Cabinet of Wonder and Awe” (Biodiversity Heritage Library)

“Deep Questions” by Keith Bond (Fine Art Review)

This mural is based on a Japanese epic tale. The hero Tamatora has recovered the pearl from the palace on the Dragon king, while she was threatened by all manner of sea monsters.

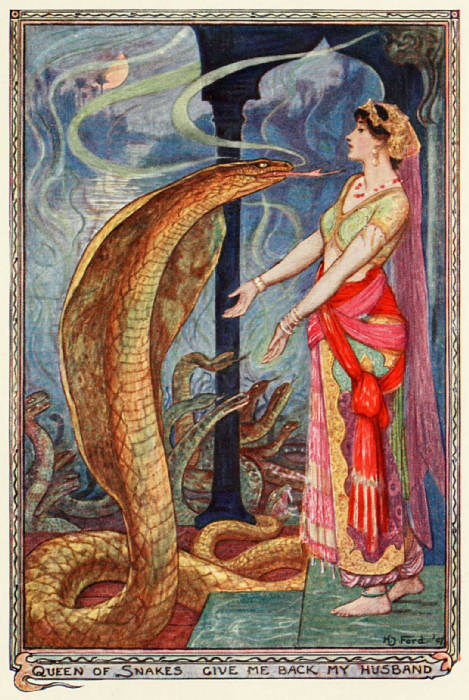

Excerpt from The Olive Fairy Tale by Andrew Lang (1907)

“At midnight there was a great hissing and rustling from the direction of the river, and presently the ground appeared to be alive with horrible writhing forms of snakes, whose eyes glittered and forked tongues quivered as they moved on in the direction of the princess’s house. Foremost among them was a huge, repulsive scaly creature that led the dreadful procession. The guards were so terrified that they all ran away; but the princess stood in the doorway, as white as death, and with her hands clasped tight together for fear she should scream or faint, and fail to do her part. As they came closer and saw her in the way, all the snakes raised their horrid heads and swayed them to and fro, and looked at her with wicked beady eyes, while their breath seemed to poison the very air. Still the princess stood firm, and, when the leading snake was within a few feet of her, she cried: ‘Oh, Queen of Snakes, Queen of Snakes, give me back my husband!’ Then all the rustling, writhing crowd of snakes seemed to whisper to one another ‘Her husband? her husband?’ But the queen of snakes moved on until her head was almost in the princess’s face, and her little eyes seemed to flash fire. And still the princess stood in the doorway and never moved, but cried again: ‘Oh, Queen of Snakes, Queen of Snakes, give me back my husband!’ Then the queen of snakes replied: ‘To-morrow you shall have him—to-morrow!’ When she heard these words and knew that she had conquered, the princess staggered from the door, and sank upon her bed and fainted. As in a dream, she saw that her room was full of snakes, all jostling and squabbling over the bowls of milk until it was finished. And then they went away.”

Kelpies are often depicted as feared water demons in Scottish, Irish, and English folklore. Similar to the Greek sirens, the shapeshifting kelpie took the form of a beautiful human or horse. Kelpies “haunted” streams and rivers and would lure innocent travellers on their back only to drown an devour them.

Excerpt from “The Kelpie of Corrievreckan” by Charles MacKay

“I have no dwelling beyond the sea,

I have no good ship waiting for thee:

Thou shalt sleep with me on a couch of foam,

And the depths of the ocean shall be thy home.”

The gray steed plunged in the billows clear,

And the maiden’s shrieks were sad to hear;––

“Maiden, whose eyes like diamonds shine—

Maiden, maiden, now thou’rt mine!”

Loud the cold sea-blast did blow.

As they sank ‘mid the angry waves below—

Down to the rocks where the serpents creep,

Twice five hundred fathoms deep.

At morn a fisherman, sailing by.

Saw her pale corpse floating high;

He knew the maid by her yellow hair

And her lily skin so soft and fair.

Under a rock on Scarba’s shore.

Where the wild winds sigh and the breakers roar,

They dug her a grave by the water clear.

Among the sea-weed salt and sere.

And every year at Beltan E’en,

The Kelpie gallops across the green.

On a steed as fleet as the wintry wind

With Jessie’s mournful ghost behind.

You can find more information about Charles MacKay here.

You can find more information about the artist Warwick Goble here.

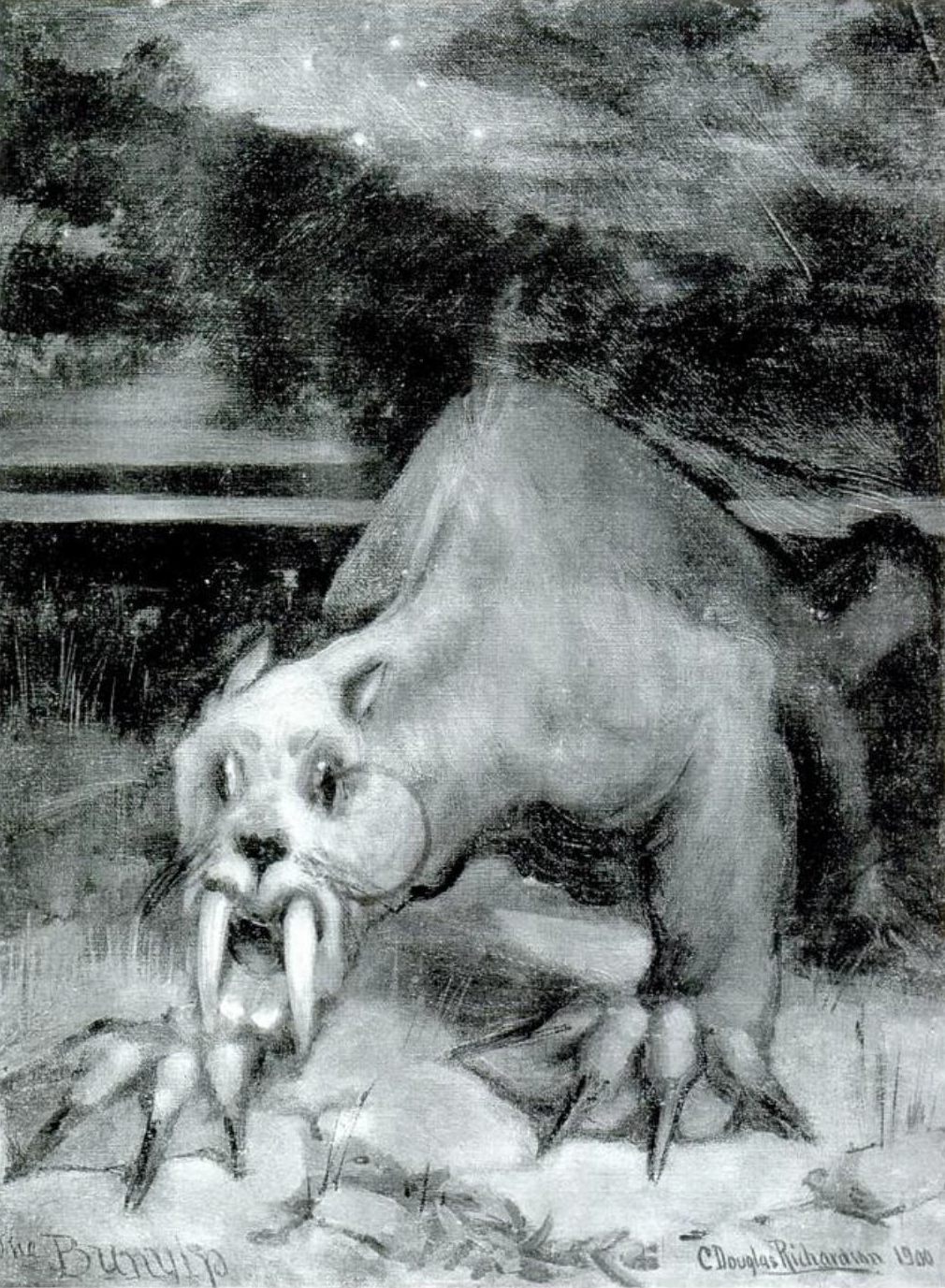

The Bunyip

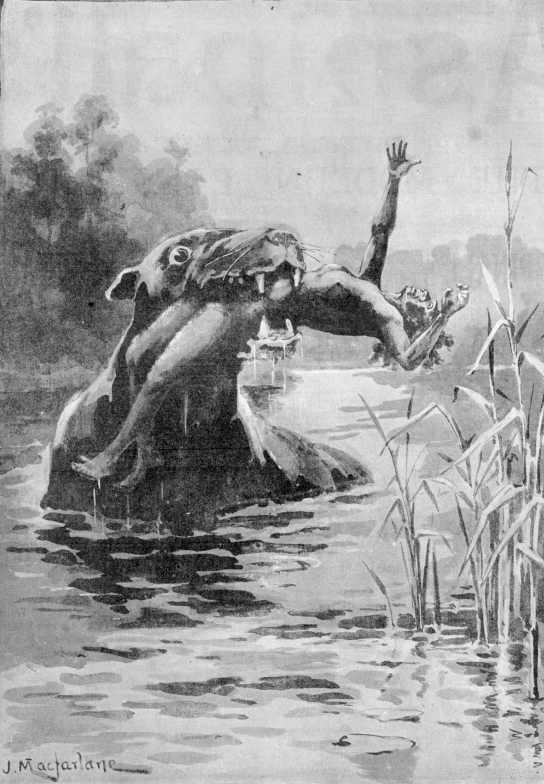

“The bunyip was an Australia water monster. The Indigenous people have lived in Australia for over 30,000 years and the stories of bunyips go back a long time. Early accounts of crocodiles and other real-life sea creatures added to the mysterious origins of the bunyips. Like Kelpies, stories about bunyips may have been cautionary warning about the hazards of the sea. While in some Indigenous Australian legends the bunyip is described as a dangerous predator, in other stories, they are featured as gentle herbivores.”

–– Excerpt from From the Dreamtime: Australian Aboriginal Legends by Jean A. Ellis (Harper Collins, 1991)

There are many legends from the Dreamtime about the large amphibious monsters, which most Australians nowadays call bunyips. Most of them how these creatures as quite ferocious, living in secluded waterholes but able to walk on land. They terrorized the people who lived nearby because they were meat eaters who stalked humans as well as animals.

Bunyip legends come from many different places and descriptions of the bunyip differ from place to place, ranging from a seal-like creature to a huge monster rather like a dinosaur. As white settlers spread through the land after the First Fleet of 1786, they were told of the fierce, man-eating bunyips and they grew to fear them….After much debate it was officially decided that bunyips existed only in people’s imaginations (Ellis, 1991, pp.85-86) Retrieve March 26, 2023

The Dreamtime

In the Australian Indigenous cultures, the Dreamtime (called “Alchera” by the northern Arunta people) is the term used to describe the specific beliefs about the creation of the world, the ancestral spirits in nature and the cosmos and the interrelationship individuals have with nature. The Dreamtime was the dynamic moment when the world came into being as a result of the explosion of energy by ancestral spirits. “So strong is the Aboriginal peoples’ identification with their ancestors that it matches their sense of individual selfhood: they feel they are essentially the same people, from age to passing age” (Allen, Fleming, & Kerrigan, 1999). Stories of the Dreamtime explain how spirit beings metamorphosed into features of the landscape. The creative energy called “Djang” can be tapped into instantaneously; through ritual and dance,“Djang” can also help individuals reunite with their ancestral spirits. Understanding the Dreamtime is central to understanding the ontology and metaphysical dimensions of Indigenous ways of knowing; stories of the Dreamtime also provided a moral template for ways of being. The geographical formations, skies, mountains, rock formations, the plains, deserts, waters, animal, and human life are interconnected with the spiritual forces of nature. Allen, Fleming, and Kerrigan write that “the boundaries which Westerners have so painstakingly erected down the millennia to separate themselves from the natural world have never existed in the minds of Aboriginal peoples. Here all-men, women, animals, and every living thing—have been called into being by the same sublime and unceasing dream” (p.14).

Colin Dean (1996) emphasizes that the philosophical aspects of the ‘Dreamtime’ are complex and that it is important not to generalize as different individuals interpret the dreamtime in very unique ways.

All aspects of the Aboriginal environment are affected by the power of the spirits. The very land itself is a kind of ‘church’; it is a kind of theophany where the land contains the essence of the Ancestors, and is the work of the Ancestors. The whole land is a religious sanctuary, with special regions throughout it which have acquired special sacred status. The Aborigines regard themselves, whether as individuals, groups, categories, sexes or genetic stock, to be in mystical communion, via the sacred places, with certain totemic beings. In this regard the whole life of the Aborigine is a ‘religious experience’. They are intimately connected with their whole environment which is pervaded by the supernatural, the result being that their experience of the whole environment is charged with numinous ambience. (p.2)

Retrieved October 12, 2022 Internet Archive: The Australian Aboriginal “Dreamtime” by Colin Dean. Gamahucher Press, West Geelong, Victoria, Australia.

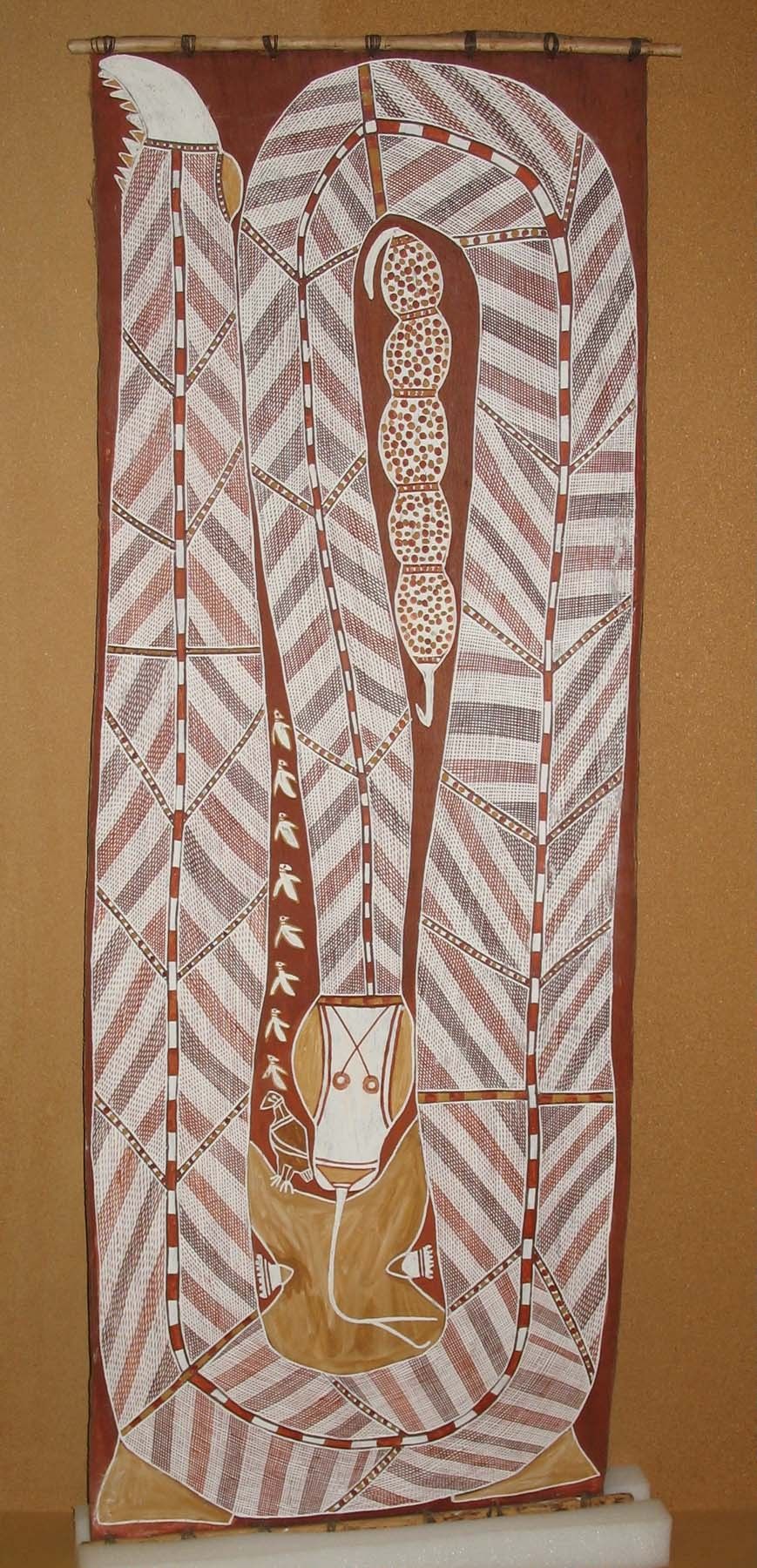

The Rainbow Serpent

Water is central to life, and for the Indigenous Australian people, the “serpent rainbow” or “rainbow snake” is one of the most omnipresent and universal spirit ancestors. The rainbow serpent which, is a symbol of water and the source of life, is represented on ancient rock and cave paintings that are thousands of years old. The “dreamtime” presence of the life giving forces of water make rivers, streams, and lakes sacred sites.

The never-ending quest for water in arid conditions defines the rhythm of existence for many Aboriginal peoples; only in the tropical north and temperate south can a ready supply be taken for granted. At the mundane level, the people have a strong sense of water’s importance, yet they are under no illusions about its immense destructive power. At a more spiritual level, the summoning of rain by rituals, and the expression of thanks to those spirits which have delivered it, are central preoccupations of religious life.

All this significance, for good and for evil, is invested symbolically in the figure of the snake whose bite may bring death and yet whose ferocious coilings carry a suggestion of the quickening impulse of life at creation’s heart; whose slender shape suggests the arcing of the rainbow, with all the fertility contained in the gently dropping rain—and with all the latent destructiveness of downpour and sudden flash flood. It is therefore scarcely surprising that the Rainbow Snake should be one of the oldest and most ubiquitous of all the Aboriginal ancestral figures (Allen, Felming, & Kerrigna, 1999, p. 32.

*************************************************************************************

For a long time they cast patiently, without receiving a single bite ; the sun had grown low in the sky, and it seemed as if they would have to go home empty-handed, not even with a basket of roots to show ; when the youth, who had baited his hook with raw meat, suddenly saw his line disappear under the water. Something, a very heavy fish, he supposed, was pulling so hard that he could hardly keep his feet, and for a few minutes it seemed either as if he must let go or be dragged into the pool. He cried to his friends to help him, and at last, trembling with fright at what they were going to see, they managed between them to land on the bank a creature that was neither a calf nor a seal, but something of both, with a long, broad tail. They looked at each other with horror, cold shivers running down their spines ; for though they had never beheld it, there was not a man amongst them who did not know what it was — the cub of the awful Bunyip (Lang, 1914, p. 72).

Retrieved: Internet Archive, October 12, 2022 https://ia902806.us.archive.org/13/items/brownfairybook00lang/brownfairybook00lang.pdf

Excerpt from “The Cry” (Mohawk First Nation, told by Peter Blue Cloud (1933-2011)

It was all darkness and always had been,

There was nothing there forever.

Creation was a tiny seed

Await a dream.

The dream came to be

Because of the cry

A howling cry which was

An echo in the emptiness of nothing.

The cry was very lonely and

Caused the dream to

Turn over in its sleep

The dream did not want to awaken

But the crying would not stop….(Peter Blue Cloud in The telling of the world, edited by S. Penn, p.16).

For more information about the poet and artist Peter Blue Cloud please open the link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Blue_Cloud

Resources:

The Project Gutenberg eBook of American Hero-Myths: A Study in the Native Religions of the Western Continent, by Daniel G. Brinton https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/11029/pg11029-images.html

Books in Mythology and Legends (Listed in Order-Project Gutenberg)

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/bookshelf/52

“In the beginning, Raven and Mink and Coyote helped the Creator plan the world. They were in on all the arguments. They helped the Creator decide to have all the rivers flowed only one way; they first thought that the water should flow up one side of the river and down on the other. They decided that there should be bends in the rivers, so that there would be eddies where the fish could stop and rest. They decided that beasts should be placed in the forests. Human beings would have to keep out of the way…” (told by Andrew Joe an recorded by Ella Clark, The Beginning of the Skagit World, in W.S. Penn (Ed.) (1996). The telling of the world. Stewart, Tabori, & Chang Publishers, p.18).

For information about Haida Gwaii stories, myths, and legends please open the link below

Internet Archive Haida Stories: https://ia800304.us.archive.org/20/items/cihm_11769/cihm_11769.pdf

The Raven in Haida Mythology https://mythicstories.com/raven-in-haida-mythology/

Excerpt from: The Metamorphoses of Ovid (Books 1-VII), Translated by Henry T. Riley (1816-1878). Philadelphia: McKay, 1899. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21765/21765-h/21765-h.htm

Middle wall: the hostile forces; Typhoeus the giant, against whom even gods fought in vain; his daughters, the three Gorgons, who symbolise lust and lechery, intemperance and gnawing care. The longings and wishes of mankind fly over their heads.”

Excerpt from “The Gorgon’s Head” in A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

“Perseus left the palace, but was scarcely out of hearing before Polydectes burst into a laugh; being greatly amused, wicked king that he was, to find how readily the young man fell into the snare. The news quickly spread abroad, that Perseus had undertaken to cut off the head of Medusa with the snaky locks. Everybody was rejoiced; for most of the inhabitants of the island were as wicked as the king himself, and would have liked nothing better than to see some enormous mischief happen to Danae and her son. The only good man in this unfortunate island of Seriphus appears to have been the fisherman. As Perseus walked along, therefore, the people pointed after him, and made mouths, and winked to one another, and ridiculed him as loudly as they dared.

“Ho, ho!” cried they; “Medusa’s snakes will sting him soundly!”

Now, there were three Gorgons alive, at that period; and they were the most strange and terrible monsters that had ever been since the world was made, or that have been seen in after days, or that are likely to be seen in all time to come. I hardly know what sort of creature or hobgoblin to call them. They were three sisters, and seem to have borne some distant resemblance to women, but were really a very frightful and mischievous species of dragon. It is, indeed, difficult to imagine what hideous beings these three sisters were. Why, instead of locks of hair, if you can believe me, they had each of them a hundred enormous snakes growing on their heads, all alive, twisting, wriggling, curling, and thrusting out their venomous’ tongues, with forked stings at the end! The teeth of the Gorgons were terribly long tusks; their hands were made of brass; and their bodies were all over scales, which, if not iron, were something as hard and impenetrable. They had wings, too, and exceedingly splendid ones, I can assure you; for every feather in them was pure, bright, glittering, burnished gold, and they looked very dazzlingly, no doubt, when the Gorgons were flying about in the sunshine.

But when people happened to catch a glimpse of their glittering brightness, aloft in the air, they seldom stopped to gaze, but ran and hid themselves as speedily as they could. You will think, perhaps, that they were afraid of being stung by the serpents that served the Gorgons instead of hair,—or of having their heads bitten off by their ugly tusks,—or of being torn all to pieces by their brazen claws. Well, to be sure, these were some of the dangers, but by no means the greatest, nor the most difficult to avoid. For the worst thing about these abominable Gorgons was, that, if once a poor mortal fixed his eyes full upon one of their faces, he was certain, that very instant, to be changed from warm flesh and blood into cold and lifeless stone! ” (Retrieved August 2, 2023 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9255/9255-h/9255-h.htm).

Artistic Versions of Medusa

The Gorgons

Excerpt from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (translation by Henry Thomas or T. Riley) (Book IV, l663-670)

“[The] Gorgons were female warriors…..Gorgons are said to have inhabited the Gorgades, islands in the 150IV. 663-670Æthiopian Sea, the chief of which was called Cerna, according to Diodorus and Palæphatus. It is not improbable that the Cape Verde Islands were called by this name. The fable of the transformation of Atlas into the mountain of that name may possibly have been based upon the simple fact, that Perseus killed him in the neighborhood of that range, from which circumstance it derived the name which it has borne ever since. The golden apples, which Atlas guarded with so much care, were probably either gold mines, which Atlas had discovered in the mountains of his country, and had secured with armed men and watchful dogs; or sheep, whose fleeces were extremely valuable for their fineness; or else oranges and lemons, and other fruits peculiar to very hot climates, 170IV. 663-673for the production of which the poets especially remarked the country of Tingitana (the modern Tangier), as being very celebrated.” ( Project Gutenberg eBook-lines 660-670, Book IV of Ovid’s Metamorphoses: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/21765/21765-h/21765-h.htm)

Project Gutenberg eBook of Ovid’s Metamorphoses was produced by: Louise Hope, Steve Schulze and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

Medusa

One of a trio of Gorgon sisters, Medusa was said to be immortal. According to Greek myth and legend, Medusa was once beautiful; she had been a devoted priestess to the goddess Athena. Athena turned Medusa into a snake-haired monster when she discovered that Medusa had an romantic affair with the sea god Poseidon. Medusa’s skin had a greenish he and if anyone looked at Medusa, they were turned into stone The Greek hero Perseus decapitates Medusa and later used her snake-girded heard as a weapon that would petrify all those who looked upon it. Medusa was the mother of the immortal winged horses Pegasus and Chrysaor.

From Book IV of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (translation by Charles Martin, 2004. W.W. Norton & Co.).

Perseus said:

“[Medusa] was at one time very beautiful,

the hope of many suitors all contending,

and her outstanding feature was her hair

(this I have learned from one who saw her then).

But it is said that Neptune (Poseidon) ravisher her,

and in the temple of Minerva (Athena), where

Jove’s daughter turned away from the outrage

and chastely had hid her eyes behind her aegis.

“So that this action should not go unpunished,

she turned the Gorgon’s hair into foul snakes;

and she, to overwhelm her foes with terror,

bears on her breast the serpents she created” ( Ovid: Metamorphoses, lines 1080- 1094; C. Martin 2004 trans. of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, pp. 155-156).

Perseus and Medusa (lines 1046-1072).

“And then by trekking though remote and distant

byways, [Perseus] came at last to where the Gorgon lived.

And everywhere, in fields, along the roads,

he witnessed the sad forms of men and beasts

no more themselves, but changed now into stone,

misfortunates, who’d glimpsed Medusa once.

[Perseus] too had once looked upon her image,

but it had been reflected in the shield

of bronze our hero bore in his left hand;

and while sleep held Medusa and her snakes,

he struck her head off; from their mother’s blood

sprang swift Pegasus and his brother both.” Lines 1060-1070, Ovid, Metamorphoses trans. by. Martin, 2004, p.. 155). (Chrysaor was Perseus’s horse).

Excerpt from Isaac Asimov’s Words from the Myths, Signet, 1969)

“An even more terrible type of ‘bird-women’were the Gorgons, a name coming from the Greek word meaning ‘terrible.’ Like the Harpies, they had wings and claws of birds, but, worst of all, their hair was made up of living, writhing snakes. They wre so horrible to look at that anyone seeing them turned to stone….

The best known of the three Gorgons which were supposed to exist was the youngest and most horrible. Her name was Medusa (me-doo’suh). She has found her way into zoology, for a jellyfish has long tentacles that writhe about in search of food, and those look like living snakes attached to a body. For that reason, such jellyfish are referred to as ‘medusas’” (Asimov, 1961, p. 75).

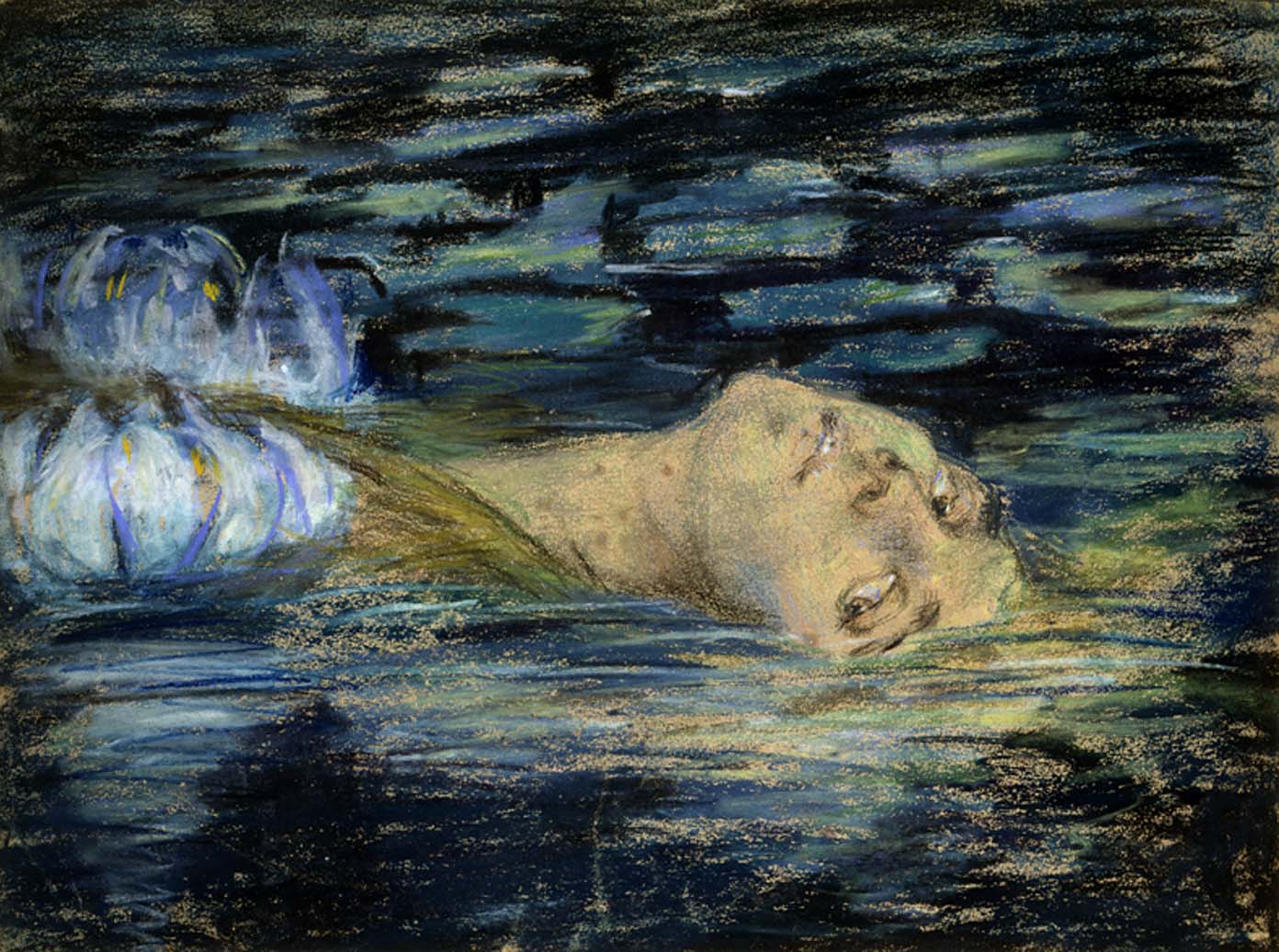

Medusa by Alice Pike Barney

To learn more about the evocative art of Alice Pike Barney, please open the link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Pike_Barney

Teaching and Learning Resources

The Myth of Perseus and Medusa Explained:

By Edward Burne-Jones – [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32102947

Perseus Tells the Story of Medusa (Excerpt from Ovid’s Metamorphosis)

“[Perseus] told of his long journeys, of dangers that were not imaginary ones, what seas and lands he had seen below from his high flight, and what stars he had brushed against with beating wings. He still finished speaking before they wished. Next one of the many princes asked why Medusa, alone among her sisters, had snakes twining in her hair. The guest replied ‘Since what you ask is worth the telling, hear the answer to your question. She was once most beautiful, and the jealous aspiration of many suitors. Of all her beauties none was more admired than her hair: I came across a man who recalled having seen her. They say that Neptune, lord of the seas, violated her in the temple of Minerva. Jupiter’s daughter turned away, and hid her chaste eyes behind her aegis. So that it might not go unpunished, she changed the Gorgon’s hair to foul snakes. And now, to terrify her enemies, numbing them with fear, the goddess wears the snakes, that she created, as a breastplate.” Retrieved March 27, 2023 https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph4.htm Metamorphoses Book IV (A. S. Kline’s Version)

From Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Book IV:663-705 Perseus offers to save Andromeda

“Aeolus, son of Hippotas, had confined the winds in their prison under Mount Etna, and Lucifer, who exhorts us to work, shone brightest of all in the depths of the eastern sky. Perseus strapped the winged sandals, he had put to one side, to his feet, armed himself with his curved sword, and cut through the clear air on beating pinions. Leaving innumerable nations behind, below and around him, he came in sight of the Ethiopian peoples, and the fields of Cepheus. There Jupiter Ammon had unjustly ordered the innocent Andromeda to pay the penalty for her mother Cassiopeia’s words.

As soon as Perseus, great-grandson of Abas, saw her fastened by her arms to the hard rock, he would have thought she was a marble statue, except that a light breeze stirred her hair, and warm tears ran from her eyes. He took fire without knowing it and was stunned, and seized by the vision of the form he saw, he almost forgot to flicker his wings in the air. As soon as he had touched down, he said ‘O, you do not deserve these chains, but those that link ardent lovers together. Tell me your name, I wish to know it, and the name of your country, and why you are wearing these fetters. At first she was silent: a virgin, she did not dare to address a man, and she would have hidden her face modestly with her hands, if they had not been fastened behind her. She used her eyes instead, and they filled with welling tears. At his repeated insistence, so as not to seem to be acknowledging a fault of her own, she told him her name and the name of her country, and what faith her mother had had in her own beauty.

Before she had finished speaking, all the waves resounded, and a monster menaced them, rising from the deep sea, and covered the wide waters with its breadth. The girl cried out: her grieving father and mother were together nearby, both wretched, but the mother more justifiably so. They bring no help with them, only weeping and lamentations to suit the moment, and cling to her fettered body. Then the stranger speaks ‘There will be plenty of time left for tears, but only a brief hour is given us to work. If I asked for this girl as Perseus, son of Jupiter and that Danaë, imprisoned in the brazen tower, whom Jupiter filled with his rich golden shower; Perseus conqueror of the Gorgon with snakes for hair, he who dared to fly, driven through the air, on soaring wings, then surely I should be preferred to all other suitors as a son-in-law. If the gods favour me, I will try to add further merit to these great gifts. I will make a bargain. Rescued by my courage, she must be mine.’ Her parents accept the contract (who would hesitate?) and, entreating him, promise a kingdom, as well, for a dowry.

Book IV:706-752 Perseus defeats the sea-serpent

See how the creature comes parting the waves, with surging breast, like a fast ship, with pointed prow, ploughing the water, driven by the sweat-covered muscles of her crew. It was as far from the rock as a Balearic sling can send a lead shot through the air, when suddenly the young hero, pushing his feet hard against the earth, shot high among the clouds. When the shadow of a man appeared on the water’ surface, the creature raged against the shadow it had seen. As Jupiter’s eagle, when it sees a snake, in an open field, showing its livid body to the sun, takes it from behind, and fixes its eager talons in the scaly neck, lest it twists back its cruel fangs, so the descendant of Inachus hurling himself headlong, in swift flight, through empty space, attacked the creature’s back, and, as it roared, buried his sword, to the end of the curved blade, in the right side of its neck. Hurt by the deep wound, now it reared high in the air, now it dived underwater, or turned now, like a fierce wild boar, when the dogs scare him, and the pack is baying around him. Perseus evades the eager jaws on swift wings, and strikes with his curved sword wherever the monster is exposed, now at the back encrusted with barnacles, now at the sides of the body, now where the tail is slenderest, ending fishlike. The beast vomits seawater mixed with purplish blood. The pinions grow heavy, soaked with spray. Not daring to trust his drenched wings any further, he sees a rock whose highest point stands above quiet water, hidden by rough seas. Resting there, and holding on to the topmost pinnacle with his left hand, he drives his sword in three or four times, repeatedly.

The shores, and the high places of the gods, fill with the clamor of applause. Cassiope and Cepheus rejoice, and greet their son-in-law, acknowledging him as the pillar of their house, and their deliverer. Released from her chains, the girl comes forward, the prize and the cause of his efforts. He washes his hands, after the victory, in seawater drawn for him, and, so that Medusa’s head, covered with its snakes, is not bruised by the harsh sand, he makes the ground soft with leaves, and spreads out plants from below the waves, and places the head of that daughter of Phorcys on them. The fresh plants, still living inside, and absorbent, respond to the influence of the Gorgon’s head, and harden at its touch, acquiring a new rigidity in branches and fronds. And the ocean nymphs try out this wonder on more plants, and are delighted that the same thing happens at its touch, and repeat it by scattering the seeds from the plants through the waves. Even now corals have the same nature, hardening at a touch of air, and what was alive, under the water, above water is turned to stone.”

(Retrieved August 2, 2023 Project Gutenberg eBook Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book IV (A. S. Kline’s Version)https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph4.htm).

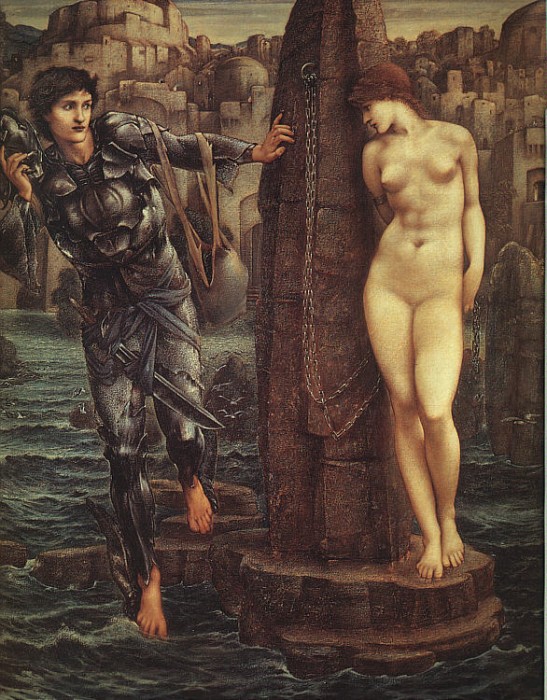

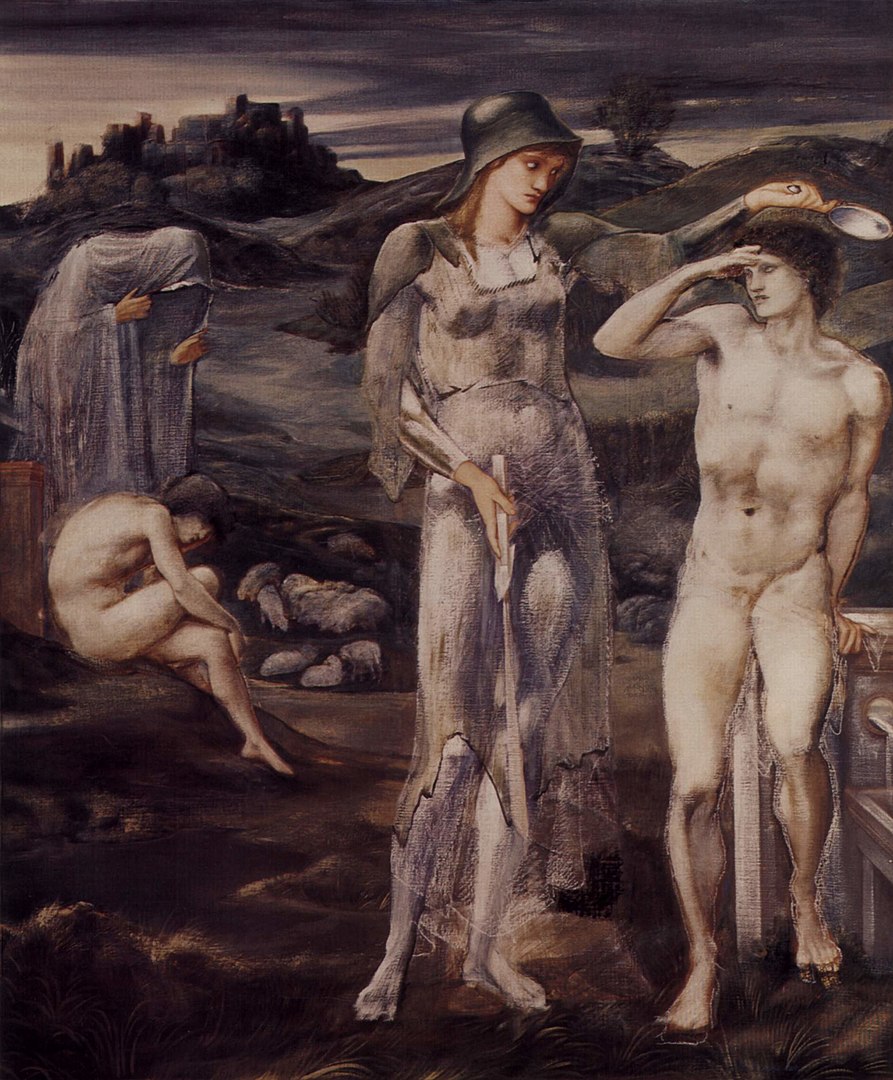

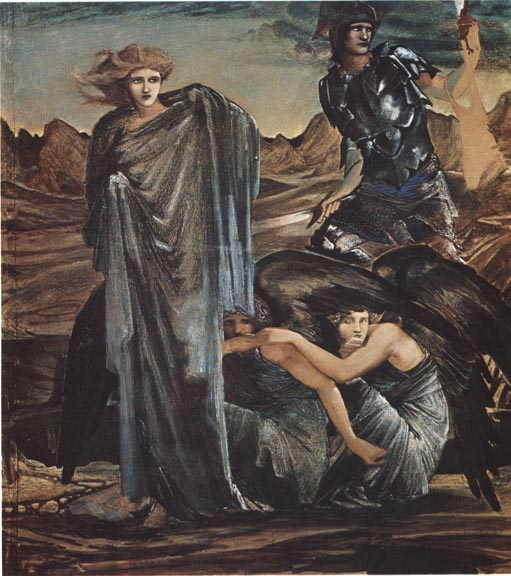

Perseus Paintings by Edward Burne Jones (1892-1833)

“In Greek Mythology, Andromeda was the daughter of the king of Ethiopia, Cepheus,and his wife, Cassiopeia. Poseidon sent the sea monster Cetus as punishment for Cassiopeia’s vanity. Chained to a rock as a sacrifice for the Cetus, Perseus saves Andromeda, marries her, and returns to Greece where Andromeda becomes queen. The theme of the “princess and the dragon” resurfaces throughout mythology, folklore, and legend. In his series of paintings, Edward Burne-Jones revives this classical myth.

Perseus and Andromeda

“Oh!” [Perseus] said. These chains don’t do you justice;

the only chains that you should wear are those

that ardent lovers put on in their passion.

But what’s your name and land of origin.,

and why are you chained up?” (Perseus to Andromeda, Metamophoses, Book IV, lines 938-931, Martin, C. 2004, p.151).

Perseus makes a promise to save Andromeda; he is helped by Athena, goddess of wisdom and war.

Book V:663-705 Perseus offers to save Andromeda

“As soon as Perseus, great-grandson of Abas, saw [Andromeda] fastened by her arms to the hard rock, he would have thought she was a marble statue, except that a light breeze stirred her hair, and warm tears ran from her eyes. He took fire without knowing it and was stunned, and seized by the vision of the form he saw, he almost forgot to flicker his wings in the air. As soon as he had touched down, he said ‘O, you do not deserve these chains, but those that link ardent lovers together. Tell me your name, I wish to know it, and the name of your country, and why you are wearing these fetters. At first she was silent: a virgin, she did not dare to address a man, and she would have hidden her face modestly with her hands, if they had not been fastened behind her. She used her eyes instead, and they filled with welling tears….”

Retrieved March 27, 2023 Ovid. The Metamorphoses (Book IV). https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph4.htm https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph4.htm

Note about the Translator Anthony S. Kline (1946-).

Retrieved from the University of Virginia Library

https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Ovhome.htm

*©Copyright 2000 A.S.Kline, All Rights Reserved

This work MAY be FREELY reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any NON-COMMERCIAL purpose.

Thanks to A. S. Kline for these generous permissions; our site is the better for his lively and accurate translation and his excellent cross-linked index-concordance (University of Virginia note).

Perseus Tells the Story of Medusa

Project Gutenberg eBook:

Ovid’s Metamorphoses translated by T. Riley.

Produced by: Louise Hope, Steve Schulze and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team03 Perseus tells the story of Medusa

Book IV: Lines 753-8

“To the three gods, he builds the same number of altars out of turf, to you Mercury on the left, to you Minerva, warlike virgin, on the right, and an altar of Jupiter in the centre. He sacrifices a cow to Minerva, a calf to the wing-footed god, and a bull to you, greatest of the gods. Then he claims Andromeda, without a dowry, valuing her as the worthiest prize. Hymen and Amor wave the marriage torch, the fires are saturated with strong perfumes, garlands hang from the rafters, and everywhere flutes and pipes, and singing, sound out, the happy evidence of joyful hearts. The doors fold back to show the whole of the golden hall, and the noble Ethiopian princes enter to a richly prepared banquet already set out for them.

When they have attacked the feast, and their spirits are cheered by wine, the generous gift of Bacchus, Perseus asks about the country and its culture, its customs and the character of its people. At the same time as he instructed him about these, one of the guests said ‘Perseus, I beg you to tell us by what prowess and by what arts you carried off that head with snakes for hair.’ The descendant of Agenor told how there was a cave lying below the frozen slopes of Atlas, safely hidden in its solid mass. At the entrance to this place the sisters lived, the Graeae, daughters of Phorcys, similar in appearance, sharing only one eye between them. He removed it, cleverly, and stealthily, cunningly substituting his own hand while they were passing it from one to another. Far from there, by hidden tracks, and through rocks bristling with shaggy trees, he reached the place where the Gorgons lived. In the fields and along the paths, here and there, he saw the shapes of men and animals changed from their natures to hard stone by Medusa’s gaze. Nevertheless he had himself looked at the dread form of Medusa reflected in a circular shield of polished bronze that he carried on his left arm. And while a deep sleep held the snakes and herself, he struck her head from her neck. And the swift winged horse Pegasus and his brother the warrior Chrysaor, were born from their mother’s blood.

For more information about the work of Olaus Magnus please open the link below.

Published in 1563 or earlier https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/3411668

The Norwegian Sea Serpent

The following extract is from a 1658 translation of Worth’s copy of Olaus Magnus’ book Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (History of the Northern Peoples, Rome, 1555). is one of the first descriptions of the Norwegian Sea Serpent:

“They who in Works of Navigation, on the Coasts of Norway, employ themselves in fishing or Merchandise, to all agree in this strange story, that there is a Serpent there which is of a vast magnitude, namely 200 foot long, and more over 20 foot thick; and is wont to live in Rocks and Caves toward the Sea-cost about Berge: which will go alone from his holes in a clear night, in Summer, and devour Calves, Lambs, and Hogs, or else he goes into the Sea to feed on Polypus, Locusts, and all sorts of Sea-Crabs. He had commonly hair hanging from his neck a Cubit long, and sharp Scales, and is black, and he hath flaming shining eyes. This Snake disquiets the Shippers, and he puts up his head on high like a pillar, and catcheth away men, and he devours them; and this hapneth not, but it signifies some wonderful changes of the Kingdom near at hand; namely that the Princes shall die, or be banished; or some Tumultous Wars shall presently follow. “ (Wikimedia, 2022).

This is an extract from Worth’s 1658 translation of Olaus Magnus’s Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Rome, 1555). It describes the Norwegian Sea Serpent in vivid descriptive detail.

Retrieved September 9, 2022, Wikimedia Commons:https://mythicalcreatures.edwardworthlibrary.ie/dragons/sea-serpent-of-norway/

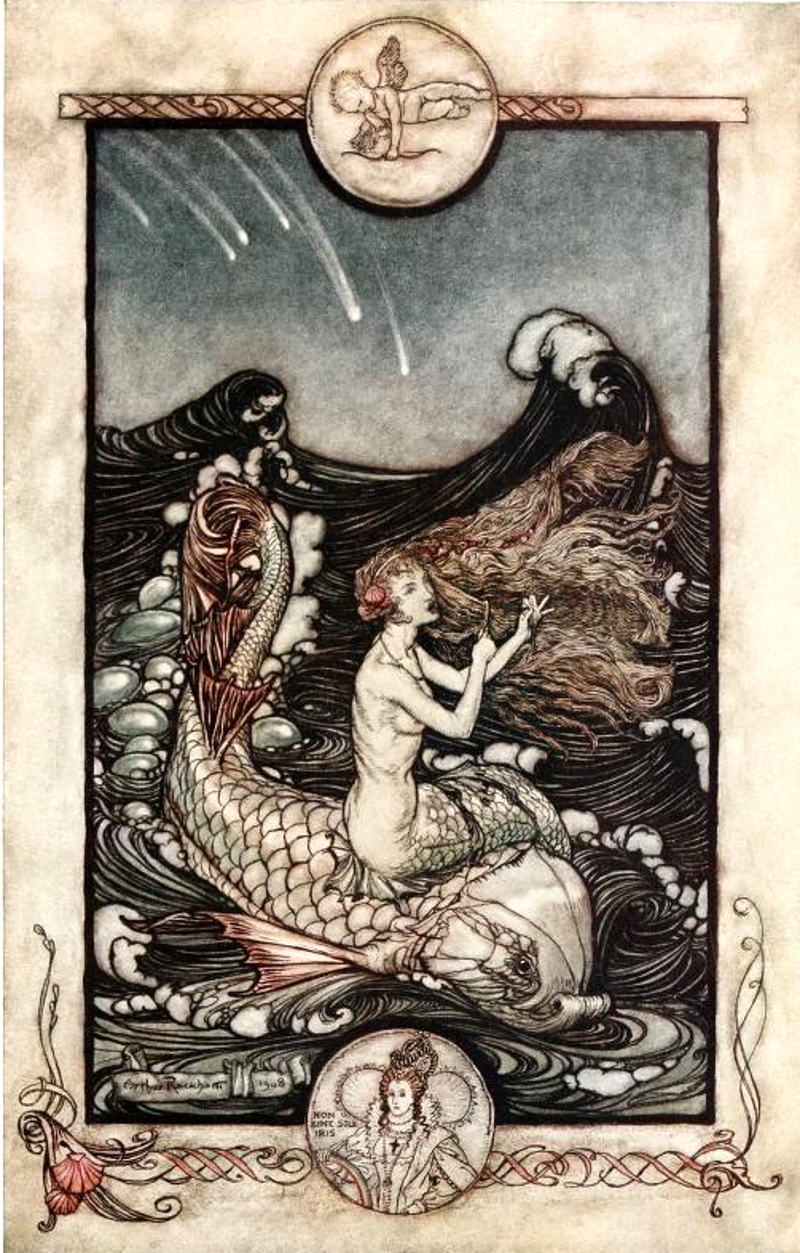

Excerpt from The Mermaid (Hans Christian Anderson and Illustrated by Edmund Dulac)

Nothing gave her greater pleasure than to hear about the world of human beings up above ; she made her old grandmother tell her all that she knew about ships and towns, people and animals. But above all it seemed strangely beautiful to her that up on the earth the flowers were scented, for they were not so at the bottom of the sea ; also that the woods were green, and that THE MERMAID the fish which were to be seen among the branches could sing so loudly and sweetly that it was a delight to listen to them. You see the grandmother called little birds fish, or the mermaids would not have understood her, as they had never seen a bird. When you are fifteen,’ said the grandmother, c you will be allowed to rise up from the sea and sit on the rocks in the moonlight, and look at the big ships sailing by, and you will also see woods and towns -excerpt from Hans Christian Anderson, (1805-1875) retold pp. 57-58, Hodder & Stoughton, 1911)

Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). Illustration from Hans Christian Anderson Tales. Hodder & Stoughton, 1911.

For the complete stories please open the link below.

Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/storiesfromhansa00anderich/page/n7/mode/2up

Mermaids, Nereids, Selkies, and Sirens

The legendary mermaid appears as a powerful feminine presence in almost all world mythologies. In the cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, mermaids were often considered semi-divine and had many supernatural qualities. Mermaids were shaped as a woman from the waist up and a fish from the navel down. The ancient Greeks believed that the union between Neptune and Tethys, the ocean created thousands of sea nymphs that would guard the depths. These sea deities (Nereids) were protective and helpful to sailors. In the Greek myths, Achilles’s mother Thetis was a nereid (Rosen, 2009). Sedna, the Inuit mother of the sea, was a central goddess of creation. Irish and Celtic folklore imagined Selkies as seals who that could transform themselves into human beings. Sirens were hypnotic mermaids with alluring voices that would lead sailors to a watery death. Naiads were water spirits/creatures that inhabited springs, lakes, and rivers (Rosen, 2009, p. 128). Kendall, Norell, & Ellis (2016) write:

“Other large sea mammals such as dugongs and manatees glimpsed at a distance by sailors too long from land, may have given rise to reported sightings of mermaids combing their long and lustrous hair. Mermaids embody the idea of beauty and danger. Perhaps the mermaids took shape in the imaginings of these sailors, adrift in the world of men on the dangerous ocean and fantasizing about the beautiful and possibly dangerous women in foreign ports….” (p.xi).

Royal Academy of Arts, London, England Note about the Painting “A Mermaid” by William Waterhouse

“Pre-Raphaelite artist John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) may have been inspired to create this work after reading Alfred Lord Tennyson’s 1839 poem A Mermaid. His painting may have been a composite inspired also by classical and mythological texts (Royal Academy of Arts, London, Piccadilly). Waterhouse was also interested in the darker mythology of the mermaid as an enchantress. Mermaids traditionally were sirens who lured sailors to their death through their captivating song. They were also tragic figures as mermaids could not survive in the human world which they yearned for and men could not exist in their watery realm, so any relationship was doomed. In Waterhouse’s painting no sailors are depicted so that despite being a ‘siren’ the mermaid is shown as an alluring rather lonely figure, albeit with a fish tail. The atmosphere evoked is one of gentle melancholy as the mermaid sits alone in an isolated inlet, dreamily combing out her long hair with her lips parted in song. Beside her is a shell.” (Retrieved September 9, 2022, Royal Academy, London https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/a-mermaid).

Excerpt from “The Mermaid” by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

The Mermaid

Who would be

Singing alone,

Combing her hair

Under the sea,

In a golden curl

With a comb of pearl,

On a throne?

II

I would be a mermaid fair;

I would sing to myself the whole of the day;

With a comb of pearl I would comb my hair;

And still as I comb’d I would sing and say,

‘Who is it loves me? who loves not me?’

I would comb my hair till my ringlets would fall

Low adown, low adown,

From under my starry sea-bud crown

Low adown and around,

And I should look like a fountain of gold

Springing alone

With a shrill inner sound

Over the throne

In the midst of the hall;

Till that great sea-snake under the sea

From his coiled sleeps in the central deeps

Would slowly trail himself sevenfold

Round the hall where I sate, and look in at the gate

With his large calm eyes for the love of me.

And all the mermen under the sea

Would feel their immortality

Die in their hearts for the love of me…..

For the complete poem, please open the link below:

https://allpoetry.com/The-Mermaid

For more information about the myth of Sedna, Inuit Goddess of the Sea please open the link below.

Sedna

The myths and legends of Inuit culture enriched and enlightened generations. These myths were foundational in terms of providing a spiritual belief system and a moral compass for interacting in the harsh climate of the artic. The oral culture of the Inuit people was very fluid and dynamic. Ballads,legends and myths had varied adaptations and their meanings were open to interpretation. One of the most famous revolves around the sea goddess known as Sedna( Nuliayuk or Taluliyuk). The ocean’s bounties were controlled by Sedna. To the Inuit, Sedna is a force of creation and essential to survival.

Sedna (from an oral ballad by Inuit elders).

“That woman down there beneath the sea,

She wants to hide the seals from us.

These hunters in the dance house,

They cannot mend matters.

They cannot mend matters.

Into the spirit world

Will go I,

Where no humans dwell.

Set matters right will I.

Set matters right will I…..”

Retrieved November 27, 2022 https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-goddess-of-the-sea-the-story-of-sedna

Eskimo Tales by Knud Rasmussen. Internet Archive.

https://archive.org/details/eskimofolktales_1706_librivox

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-goddess-of-the-sea-the-story-of-sedna

White Eskimo : Knud Rasmussen’s fearless journey into the heart of the Arctic https://archive.org/details/whiteeskimoknudr0000bown/page/n391/mode/2up

Arctic Myth and Culture: Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/inuitimagination0000seid/page/n3/mode/2up\

For more examples of the brilliant illustrations of Arthur Rackham please open the link below:

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/6335

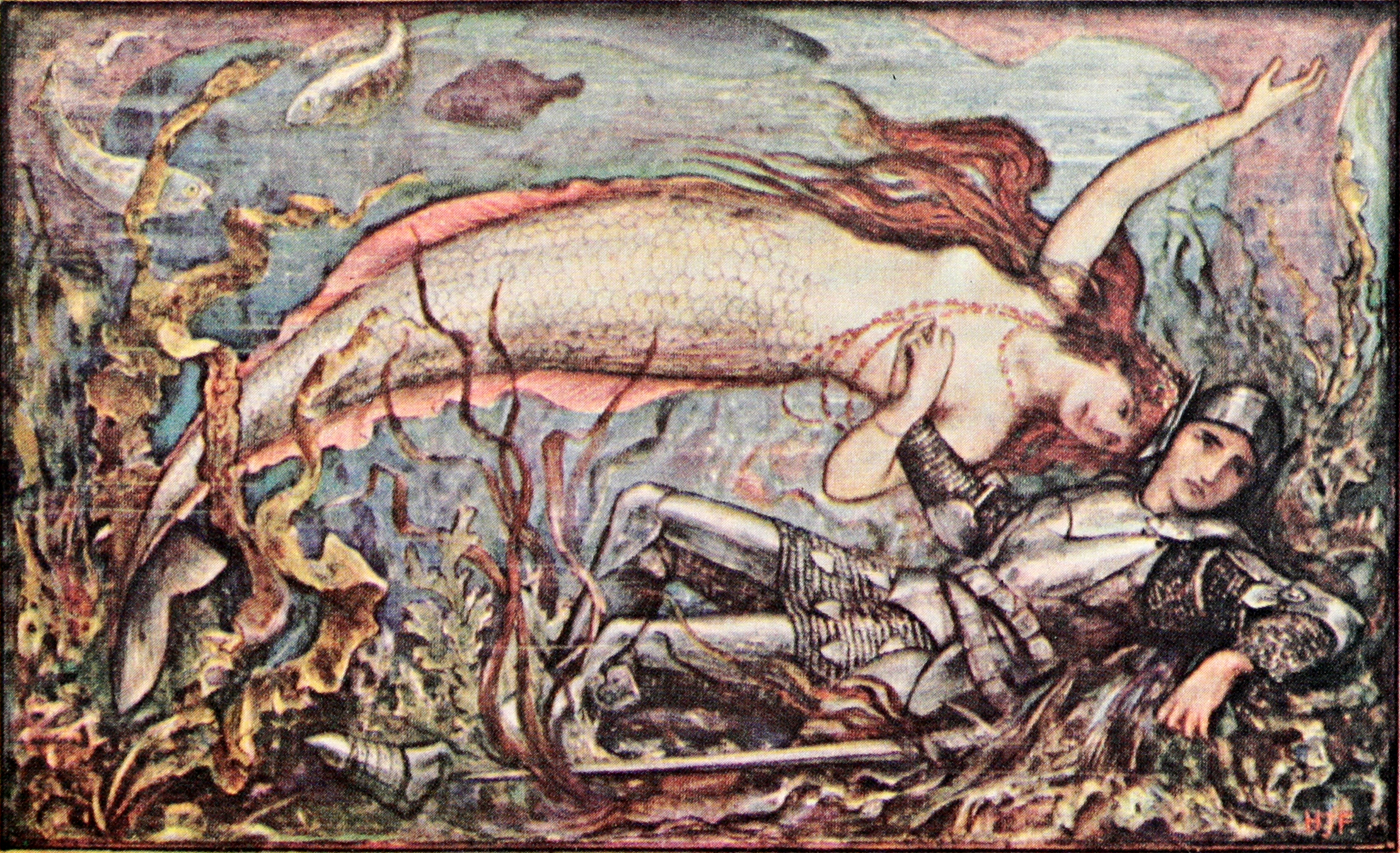

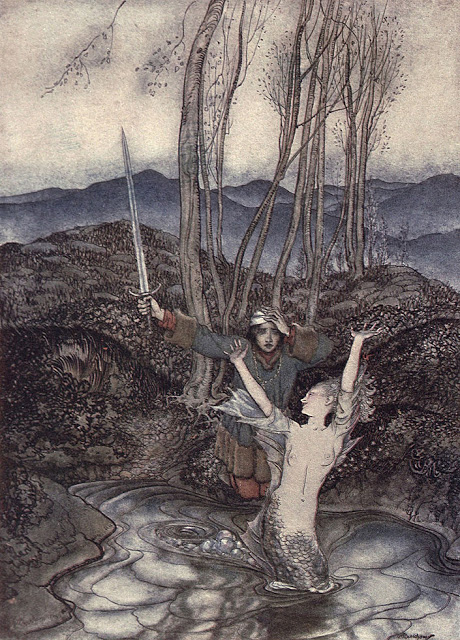

“Clerk Coleville” (British Ballad) or “The Mermaid” (From Ballads Weird and Wonderful (1912) where it was illustrated by Vernon Hill).

Ignoring the advice of his mother or lady friend, Clerk Colvill goes to a lake and is seduced by a mermaid who tells him that unless he joins her he will die. He head begins to achive and he returns home to die. There are different versions of this old British ballad. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clerk_Colvill

Clerk Colvil and his gay ladies

As they walked in the garden green,

The belt about her middle jimp

Cost Clerk Colvill of crowns fifteen.

‘ O promise me now, Clerk Colvill, Or it will cost ye muckle strife, Ride never by the wells of Slane,

If ye wad live and brook your life.’

‘ Now speak nae mair, my gay ladie,

Now speak nae mair of that to me ; For I ne’er saw a fair woman

I like so well as thee.’

(jimp = slim. brook = enjoy).

He ‘s ta’en leave o’ his gay lady,

Nought minding what his lady said,

And he ‘s rode by the wells of Slane,

Where washing was a bonny maid.

‘ Wash on, wash on, my bonny maid,

That wash sae clean your sark of silk.’

‘ And weel fa’ you, fair gentleman,

Your body whiter than the milk.’ He ‘s ta’en her by the milk-white hand,

He ‘s ta’en her by the sleeve sae green, And he ‘s forgotten his gay ladie,

And he ‘s awa’ with the fair maiden.

Then loud, loud cry’d the Clerk Colvill,

‘ O my head it pains me sair.’

‘ Then take, then take,’ the maiden said,

‘ And frae my sark you ‘cut a gare.’

Then she ‘s gied him a little bane-knife,

And frae her sark he cut a share ; She ‘s ty’d it round his whey-white face, But ay his head it aked mair. Then louder cry’d the Clerk Colvill,

‘ O sairer, sairer akes my head.’

‘ And sairer, sairer ever will,’ The maiden crys,

‘ till you be dead.’ Out then he drew his shining blade,

And thought wi’ it to be her dead,

But she has vanished to a fish, And merrily sprang into the fleed.

(sark = shirt. weelfa’ = well befall. gare = a strip. fleed = flood)

He’s mounted on his berry-broun steed,

And dowie, dowie rade he hame,

And heavily, heavily lighted doun

When to his ladie’s bower he came.

‘ O mother, mother, lay me doun,

My gentle lady, make my bed,

O brother, take my sword and spear, For I have seen the false mermaid.’

Retrieved November 21, 2022 Internet Archive https://ia803400.us.archive.org/12/items/somebritishballa00rack/somebritishballa00rack.pdf

The Demon Lover (English Ballad) From Tales Weird and Wonderful (by Richard Pearse Chope, 1862-1938).

She set her foot upon the ship,

No mariners could she behold ;

But the sails were o’ the taffetie,

And the masts o’ beaten gold.

They hadna sail’d a league, a league,

A league but barely three.

When dismal grew his countenance.

And drumly grew his ee.

The masts that were like beaten gold.

Bent not on the heaving seas ;

The sails that were o’ taffetie,

Fiird not in the east land breeze.

They hadna sail’d a league, a league,

A league but barely three,

Until she espied his cloven hoof.

And she wept right bitterlie.

” O baud your tongue, my sprightly flower,

Let a’ your moanin‘ be ;

I will show you how the lilies grow

On the banks of Italy.”

” O what hills are yon, yon pleasant hills,

That the sun shines sweetly on ? “

—

” O yon are the hills o’ heaven,” he said,

” Where you will never win.”

—

” O whatten a mountain ‘s yon,” she said,

” Sae dreary wi‘ frost and snow ? “

—

” O yon is the mountain o’ hell,” he cried,

“Where you and I will go.”

And aye when she turn’d her round about.

Aye taller he seem’d to be ;

Until that the tops o’ that gallant ship

Nae taller were than he.

The clouds grew dark, and the winds grew loud.

And the tears fill’d her ee ;

And waesome wail’d the snaw-white sprites

Upon the gurly sea.

He strack the tapmast wi‘ his hand.

The foremast wi‘ his knee ;

And he brak that gallant ship in twain.

And sank her in the sea.

(Retrieved March 28, 2023 from Internet Archive/Project Gutenberg Tales Weirds and Wonderful illustrated by Vernon Hill). https://ia902700.us.archive.org/7/items/balladsweirdwond00choprich/balladsweirdwond00choprich.pdf

The Demon Lover Notes about this Legendary Ballad

Over the years, various versions of this ballad have been written. “The Demon Lover” Can be found in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads collected by Francis James Child. Newer versions of the ballad were recorded in the 19th and early-mid 20th century.

A Warning to Married Women-Child’s Anthology

The oldest version of the ballad A Child’s Anthology is attributed to Laurence Price, a well-known ballad writer. The original, full title was call”A Warning for Married Women” and it described the experiences of Jane Reynolds and her lover James Harris.

Wikipedia Note:

“A Warning for Married Women”tells the story of Jane Reynolds and her lover James Harris, with whom she exchanged a promise of marriage. He is pressed as a sailor before the wedding takes place and Jane faithfully awaits his return for three years, but when she learns of his death at sea, she agrees to marry a local carpenter. Jane gives birth to three children and for four years the couple lives a happy life. One night, when the carpenter is away, the spirit of James Harris appears. He tries to convince Jane to keep her oath and run away with him. At first she is reluctant to do so, because of her husband and their children, but ultimately she succumbs to the ghost’s pleas, letting herself be persuaded by his tales of rejecting the royal daughter’s hand and assurance that he has the means to support her – namely, a fleet of seven ships. The pair then leaves England, never to be seen again, and the carpenter commits suicide upon learning that his wife is gone. The broadside ends with a mention that although the children were orphaned, the heavenly powers will provide for them. “(Retrieved March 28, 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Daemon_Lover)

To read the short story “The Demon Lover” (inspired by the ballad) by Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973), please open the link below.

https://jerrywbrown.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Demon-Lover-Bowen-Elizabeth.pdf

*Vernon Hill illustrated the 1912 edition of Ballads Weird and Wonderful (by Richard Pearse Chope). Born in Halifax, Yorkshire, UK, Hill became a well-known illustrator and sculpture.

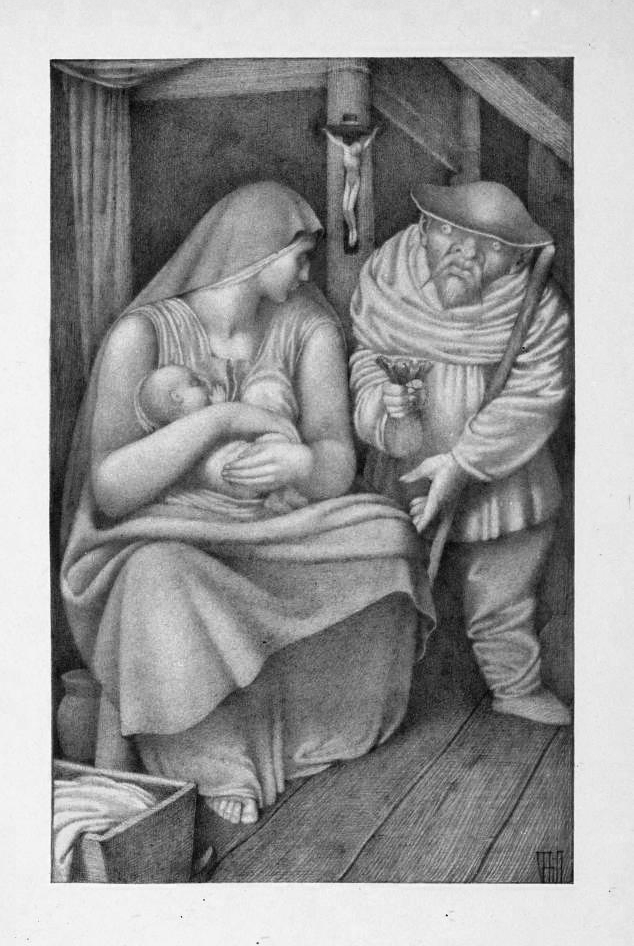

The Great Silkie of Sule Skerrie(old Scottish ballad by RIchard Pearse Chope (1862-1938)

An earthly nourice sits and sings.

And aye she sings, ” Ba, lily wean ! Little ken I my bairn’s father.

Far less the land that he staps in.”

Then ane arose at her bed-foot,

And a grumly guest I’m sure was he : ” Here am I, thy bairn’s father.

Although I be not comelie.

” I am a man upon the Ian’,

And I am a sealchie in the sea ; And when I’m far and far frae Ian’,

My dwelling is in Sule Skerrie.”

—

” It was na weel,” quo’ the maiden fair, ” It was na w6el, indeed,” quoth she, ” That the Great Sealchie of Sule Skerrie

Should hae come and aught a bairn to me.”

II

Now he has ta’cn a purse of gowd,

And he has put it upon her knee.

Saying, ” Gie to me my little young son,

And tak‘ thee up thy nourice-fee.

” And it shall pass on a summer’s day,

When the sun shines hot on every stane,

That I will take my little young son. And teach him for to swim the faem.

” And thou shalt marry a proud gunner.

And a proud gunner I’m sure he’ll be,

And the very first shot that e’er he shoots.

He’ll shoot baith my young son and me.’*(Retrieved March 28, 2023 Internet Archive: https://ia902700.us.archive.org/7/items/balladsweirdwond00choprich/balladsweirdwond00choprich.pdf)

Summary of “The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry” (Orkney Islands, Scotland)

“The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry” or “The Grey Selkie of Sule Skerry” is a traditional folk song from Shetland and the Orkney Islands, Scotland. . A woman has her child taken away by its father, the great selkie of Sule Skerry which can transform from a seal into a human. The woman is fated to marry a gunner who will harpoon the selkie and their son.

“The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry” is a short version from Shetland published in the 1850s and later listed as Child ballad number 113. “The Grey Selkie of Sule Skerry” is the title of the Orcadian texts, about twice in length. There is also a greatly embellished and expanded version of the ballad called “The Lady Odivere”.” (Retrieved March 28, 2023.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Silkie_of_Sule_Skerry).

Type your textbox content here.

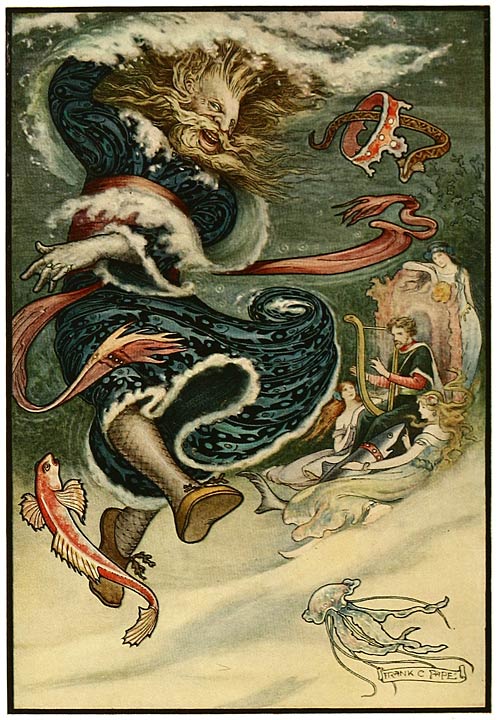

Sadko is the main character in the East Slavic epic poem Bylina. Sadko was a musician, merchant, and adventurer. For more details about Sadko and his underwater world adventure please open the link below. Arthur Ransome translated the bylina in 1916 in Old Peter’s Russian Tales.

In Repin’s beautiful painting, the Tsar of the Sea asks Sadko to choose one of the mermaids/women in the procession to marry.

The Story of Sadko:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sadko

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ilya_Repin_-_Sadko_-_Google_Art_Project_levels_adjustment_2.jpg

Internet Archive: Old Peter’s Russian Tales retold by Arthur Ransome (1884-1967) and illustrated by Dmitri Mitrokhin (1883-1973). Thomas Nelson & Sons.

https://ia600304.us.archive.org/15/items/oldpetersrussian00rans/oldpetersrussian00rans.pdf

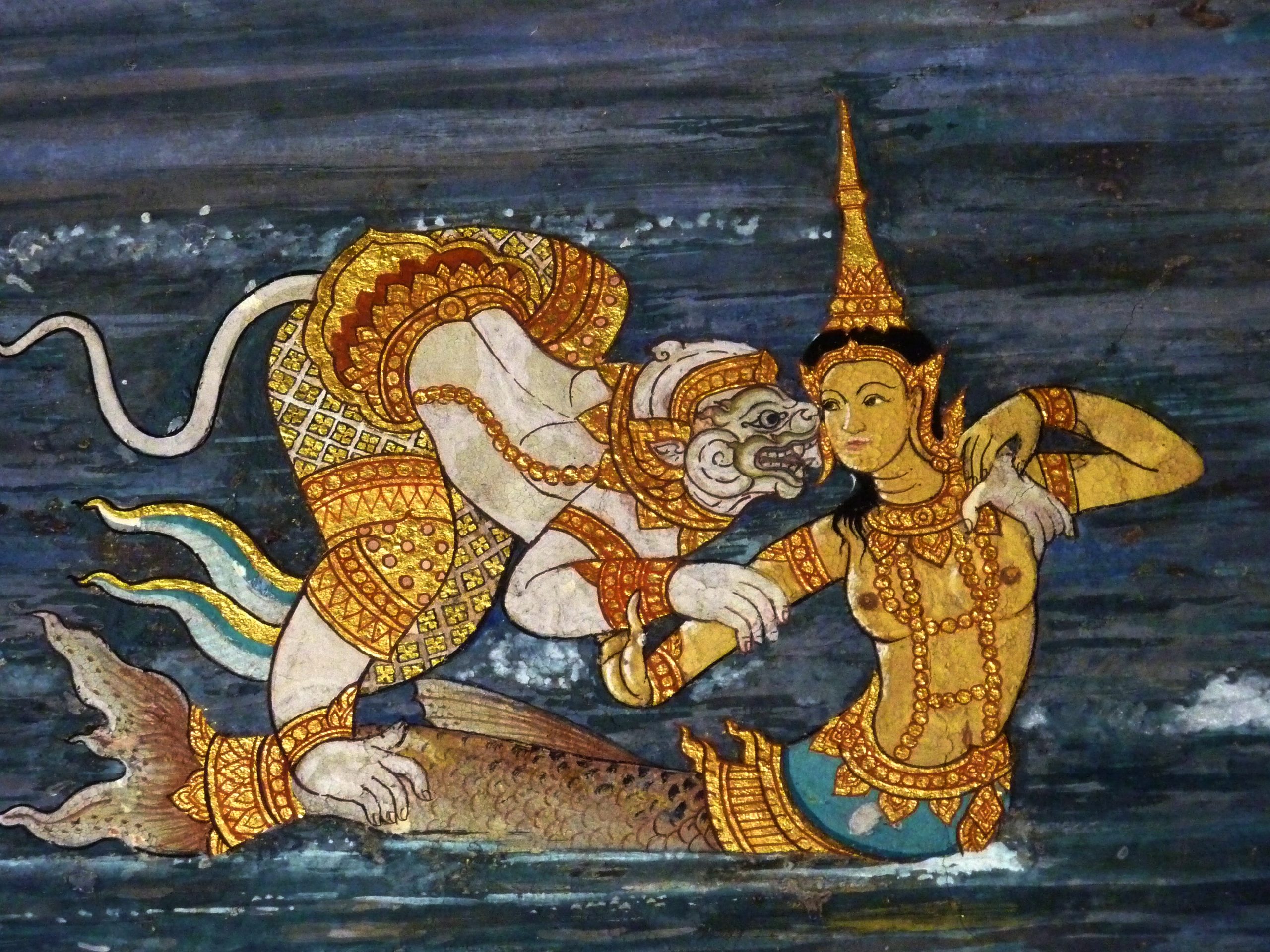

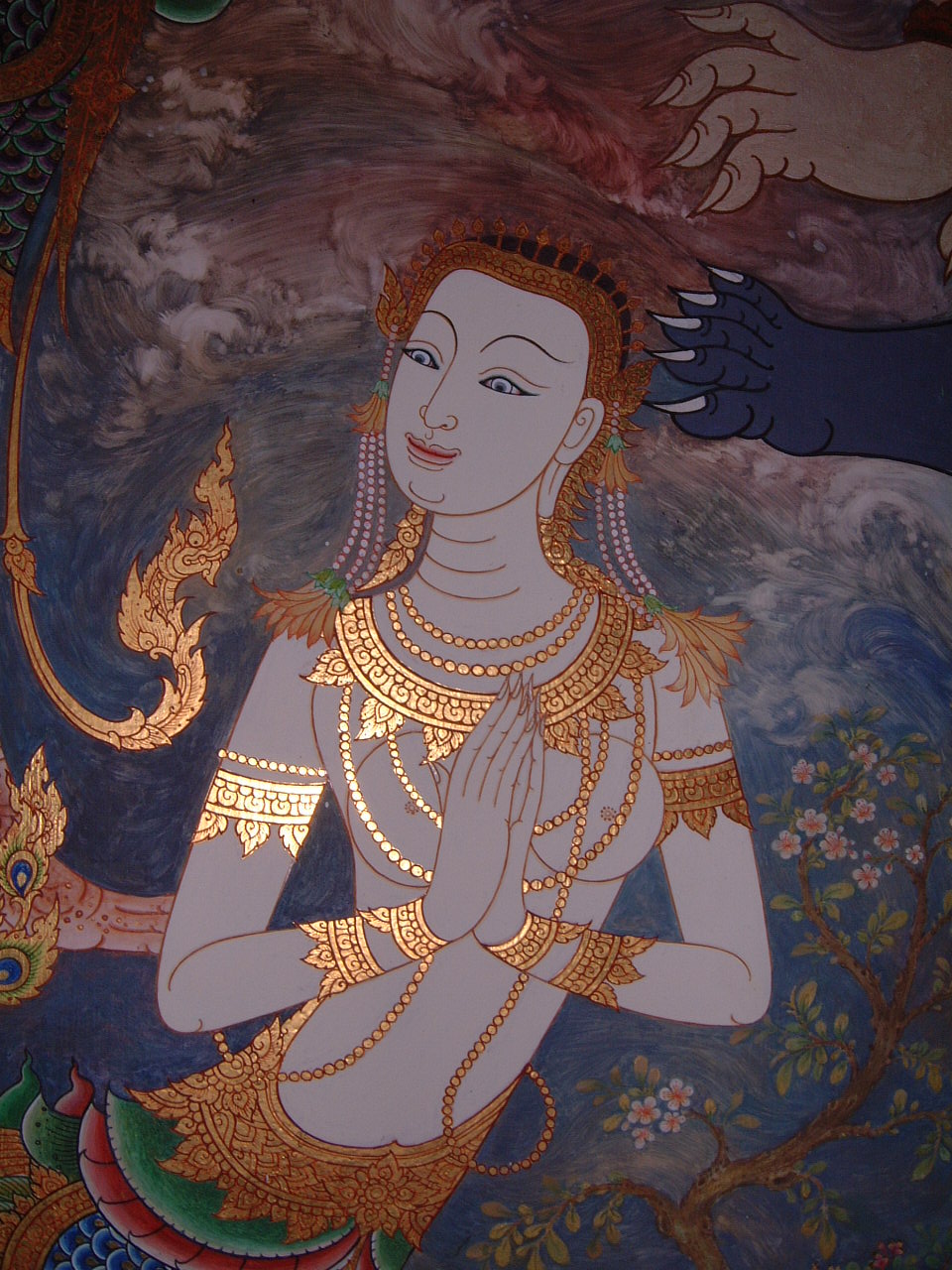

Hanuman (Anjanaya) was a divine companion of the god Rama. He is a central character in the Thai epic of the Ramakien (the Ramayana, in Hindu).

In this mural panting, the Suvannamaccha (Golden Fish Mermaid) meets Hanuman who is trying to build a bridge of stones across the sea. She falls in love with him and ends up helping him.

Fairy tale Illustrations:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Fairy_tale_illustrations

Art Institute of Chicago Note about Arnold Böcklin’s “In the Sea”

“ Arnold Böcklin’s art had little in common with Impressionism or the academic art of his time. Instead, his depictions of demigods in naturalistic settings interpret themes from Classical mythology in an idiosyncratic, often sensual manner. In the Sea, part of a series of paintings of mythological subjects, displays an unsettling, earthy realism. Mermaids and tritons frolic in the water with a lusty energy and abandon verging on coarseness. Occupying the center of the composition is a harpplaying triton. Three mermaids have attached themselves to his huge frame as if it were a raft; the one near his shoulder seems to thrust herself upon him. The work’s sense of boisterousness is tempered by the ominously shaped reflection of the triton and mermaids in the sea and by the oddness of the large-eared heads that emerge from the water at the right. In addition to imaginative, bizarre interpretations of the Classical world, Böcklin painted mysterious landscapes punctuated by an occasional lone figure. These haunting later works made him an important contributor to the international Symbolist movement. They also appealed to some Surrealist artists, particularly Giorgio de Chirico, who declared, “Each of [Böcklin’s] works is a shock.” Retrieved November 29, 2022 Art Institute of Chicago. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/110507/in-the-sea

“The Merman” by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

Who would be

A merman bold,

Sitting alone,

Singing alone

Under the sea,

With a crown of gold,

On a throne?

I would be a merman bold,

I would sit and sing the whole of the day;

I would fill the sea-halls with a voice of power;

But at night I would roam abroad and play

With the mermaids in and out of the rocks,

Dressing their hair with the white sea-flower

And holding them back by their flowing locks

I would kiss them often under the sea,

And kiss them again till they kiss’d me

Laughingly, laughingly;

And then we would wander away, away,

To the pale-green sea-groves straight and high,

Chasing each other merrily.

There would be neither moon nor star;

But the wave would make music above us afar —

Low thunder and light in the magic night…..

Courtesy: Complete Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

(Project Gutenberg)

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59279/59279-h/59279-h.htm

The Mermaid and The Merman are early poems by Alfred Lord Tennyson.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/8601/8601-h/8601-h.htm

The Sea-fairies

Slow sail’d the weary mariners and saw,

Betwixt the green brink and the running foam,

Sweet faces, rounded arms, and bosoms prest

To little harps of gold; and while they mused,

Whispering to each other half in fear,

Shrill music reach’d them on the middle sea….

Year: 1911 (1910s)

Authors: Baum, L. Frank (Lyman Frank), 1856-1919 Neill, John R. (John Rea), ill

Subjects:

Publisher: Chicago : Reilly & Britton

Contributing Library: New York Public Library

Digitizing Sponsor: MSN

Year: 1911 (1910s)

Authors: Baum, L. Frank (Lyman Frank), 1856-1919 Neill, John R. (John Rea), ill

Excerpt:

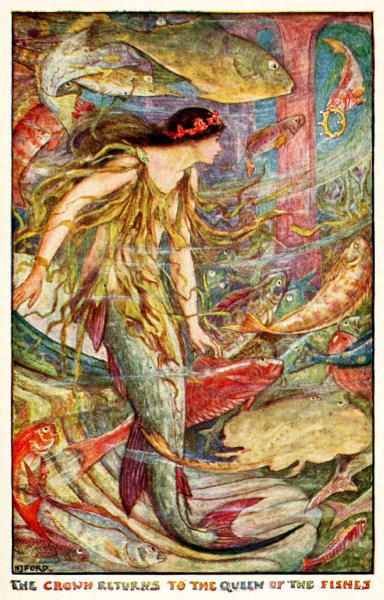

A silence fell on all the crowd, and even the grumblers held their peace and gazed like the rest. On and on came the fish, holding the crown tightly in her mouth, and the others moved back to let her pass. On she went right up to the queen, who bent, and taking the crown, placed it on her own head. Then a wonderful thing happened. Her tail dropped away or, rather, it divided and grew into two legs and a pair of the prettiest feet in the world, while her maidens, who were grouped around her, shed their scales and became girls again. They all turned and looked at each other first, and next at the little fish who had regained her own shape and was more beautiful than any of them (Andrew Lang, The Orange Fairy Book, p. 234, Longmans, Green, & Co. 1906).

Retrieved October 13, 2022 Project Gutenberg.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/36532/36532-h/36532-h.htm#illo41

Internet Archive

https://ia902802.us.archive.org/13/items/orangefairybook00lang/orangefairybook00lang.pdf

Resources

For more information about mermaids, please open the Biodiversity Heritage Library link to “The Beautiful Monster: Mermaids”.

https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2014/10/the-beautiful-monster-mermaids.html

Myths of Japan

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45723/45723-h/45723-h.htm

https://ia902704.us.archive.org/4/items/mythslegendsofja00davi/mythslegendsofja00davi.pdf

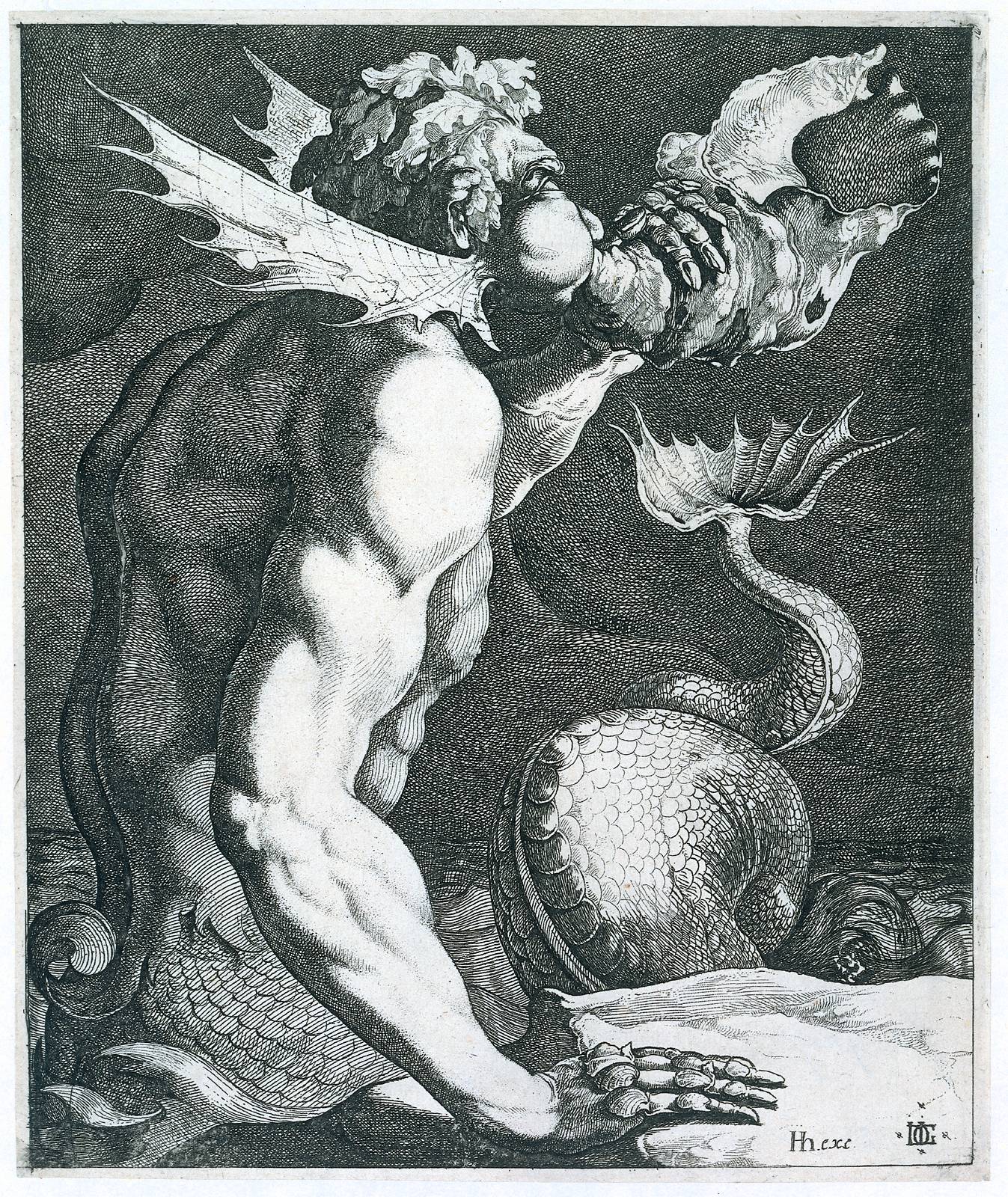

Triton, the son of Poseidon and Amphitrate was a merman and a messenger god of the sea. He lived in a golden palace at the bottom of the sea. He used the conch shell as a trumpet to control the waves of the sea.

See Also: Poseidon, Amphitrite

Source: https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/Figures/Triton/triton.html

Kinnara, Thai

Hoping to warn the city of Troy that the Greeks (the Spartans in Homer’s “The Iliad” ) were bringing the “gift” of a Trojan horse that was actually filled with warriors, Laocoön and his sons are attacked by giant serpents sent by the gods.

Classical References:

For complete references to The Odyssey and The Iliad (the art images are directly related to the descriptions in Homer’s epic texts), please open the links below.

Samuel Butler translations (2022 updated):

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1727/1727-h/1727-h.htm

Alexander Pope translation of The Iliad (updated, 2022).

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1727/1727-h/1727-h.htm

Albertus Seba: Hydra. Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Albertus Seba’s Cabinet of Wonder and Awe

“Contrary to what one might think, a curiosity cabinet is not a piece of furniture, rather it is an entire room(s) dedicated to the collection of objects that are meant to bring shock, awe, inspiration, and stimulating conversation to its viewers. During the 16th-19th centuries, the curiosity cabinet became a popular way for aristocrats and aspiring bourgeoisie to show off personal wealth and erudition. These “rooms of wonder” are considered the precursors to the modern museum. However, unlike a museum collection that is organized around a specific theme e.g. archaeology, art, natural history, and sculpture, a cabinet of curiosities celebrates its own bedlam, juxtaposing disparate objects in a jumbled mass to prompt serendipitous discoveries, new connections, and eureka! moments about the manifest world. By the 18th century, order began to coalesce out of chaos and curiosity cabinets became a bit more focused. Such was the case with a famed apothecary from Amsterdam, Albertus Seba, and his cabinet of natural history curiosities. Today, we will examine what exactly was in Seba’s celebrated collection and see if we can still find hints of the fabulous, wondrous, exotic, and down-right strange.”

Retrieved, Biodiversity Heritage Library March 26,

2023https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2013/01/curiositycabinet.html)

For Further Research:

A Wonder Room – every school should have one | Teaching | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2011/may/31/wonder-room-nottingham-university-academy

Article: New discoveries

For the complete text of The Red Book of Animal Stories, please open the link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38208/38208-h/38208-h.htm

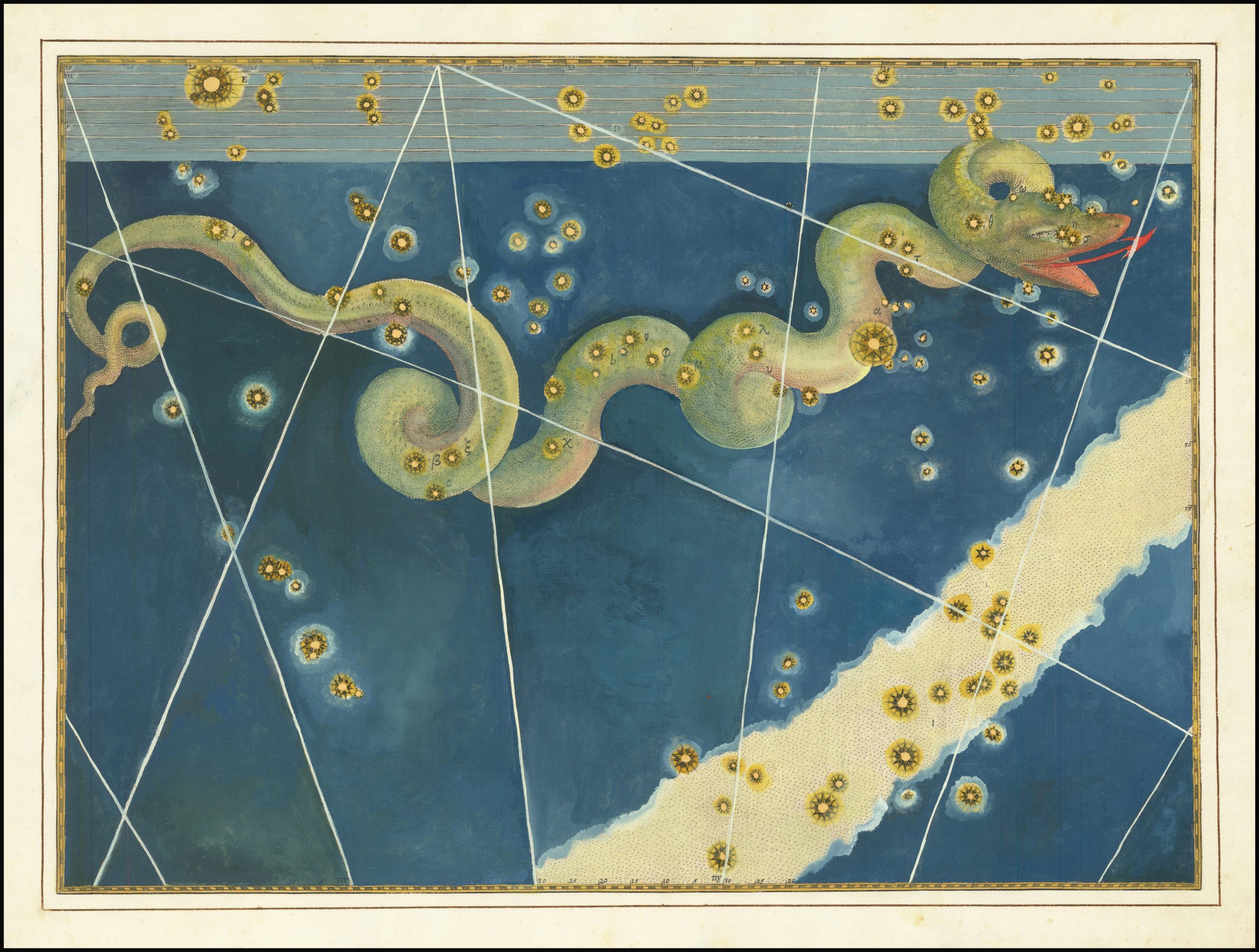

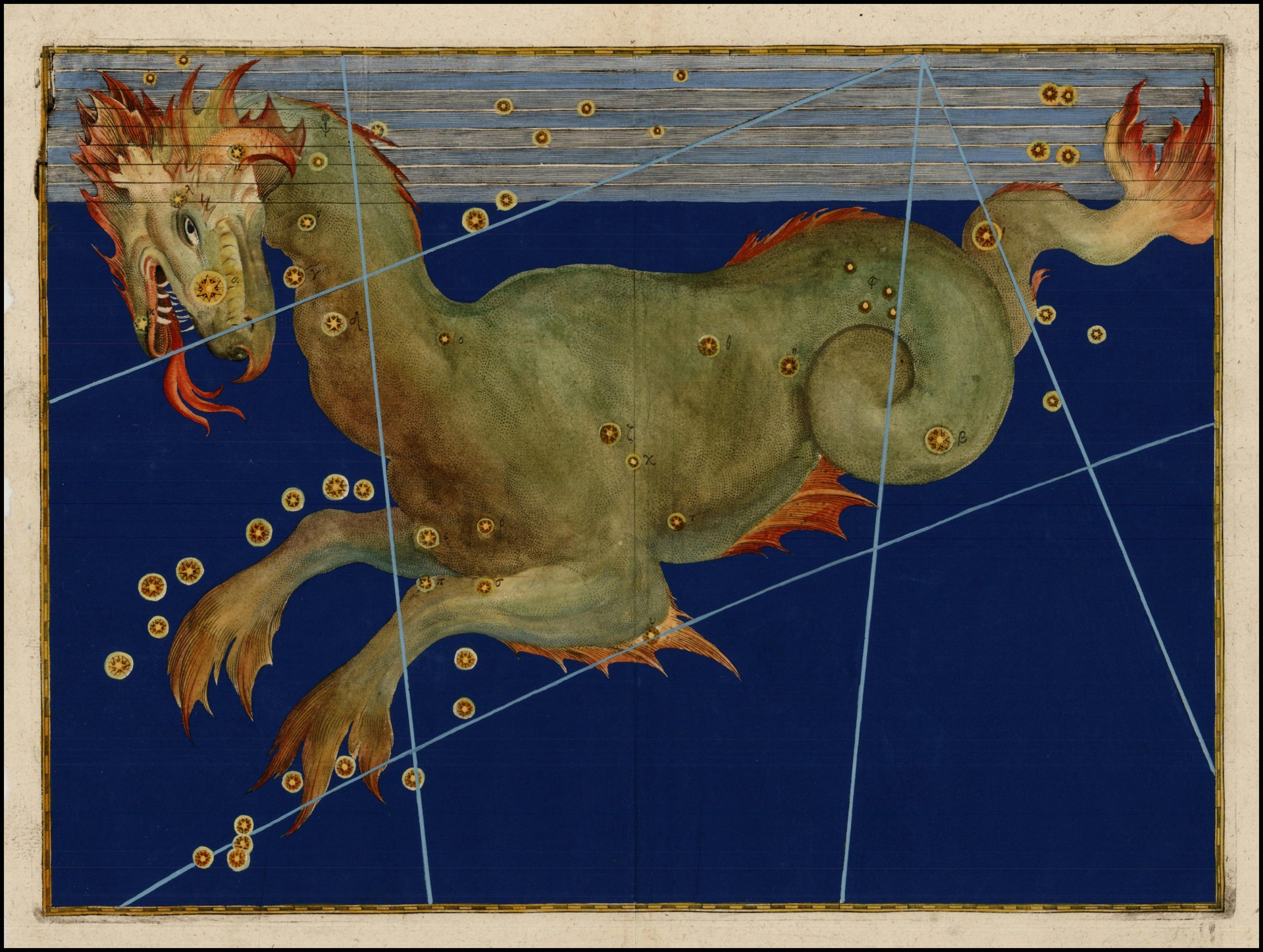

Johann Bayer’s Artistic and Imaginative Constellations. Bayer drew each constellation with a new method; the renderings were then engraved on copper plates. Being the first atlas to artistically chart the complete celestial sphere, The Unametria was published in Augsburg, Germany in 1603 by Christoph Mangle (Christophorus Mangus). The word “uranomatria” originates in the Greek word for Urania (the muse of the heavens) and “Uranos” (meaning sky or heavens). The word “matria” refers to measurement (hence the translation of Uranometria is “measuring the heavens”). Bayer’s art charted the constellations with fantastical creatures and deities. Retrieved October 13, 2022 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uranometria