14 In the Air: Winged Beings

Artists have used their imaginations to create vivid representations of myths, legends, and folktales that focus on birds, horses and other winged creatures that have magical powers. In this section, some of the art images are complemented with poems or folk and fairytale excerpts. Links to the complete stories are provided.

The Phoenix: Hope and Regeneration

The Phoenix Bird

The phoenix bird is a symbol of renewal, rebirth, and transformation. Over the millennia, artists have depicted the phoenix as a great multi-colored bird, rising from the ashes.

Kendell, Norell, and Ellis (2016) write:

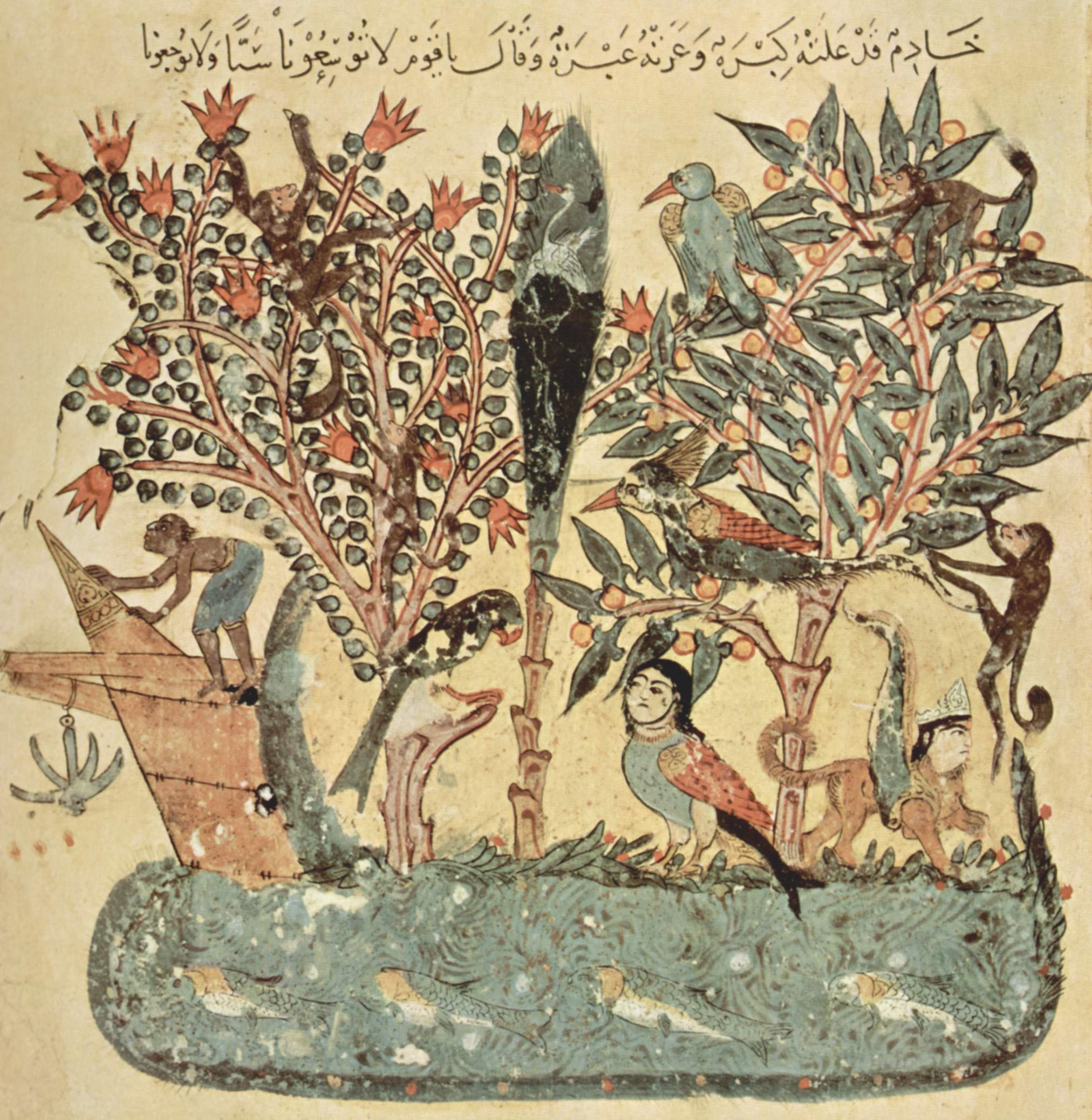

“Divine birds appear in legends of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East—from China and Japan to ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and beyond. These creatures are said to come from a sacred realm and rarely visit the earth. When they did, they may be seen as a sign that a new era has begun or that a wise leader has taken the throne. Often linked with fire and the sun, these immortal birds bring messages of peace, renewal, and good fortune.” ( Kendall, Morrell, and Ellis, 2016, p.116).

“The Phoenix” (Nepenthe) by George Darley

O Blest unfabled Incense Tree,

That burns in glorious Araby,

With red scent chalicing the air,

The earth-life grow Elysian there!

Half buried to her flaming breast

In this bright tree she makes her nest,

Hundred-sunned Phœnix! when she must

Crumble at length to hoary dust;

Her gorgeous death-bed, her rich pyre

Burnt up with aromatic fire;

Her urn, sight-high from spoiler men,

Her birthplace when self-born again.

The mountainless green wilds among,

Here ends she her unechoing song:

With amber tears and odorous sighs

Mourned by the desert where she dies.

For more information about the poem, please open the link here: https://www.poetry.com/poem/14913/nepenthe

The Firebird

The Firebird in Russian Folklore:

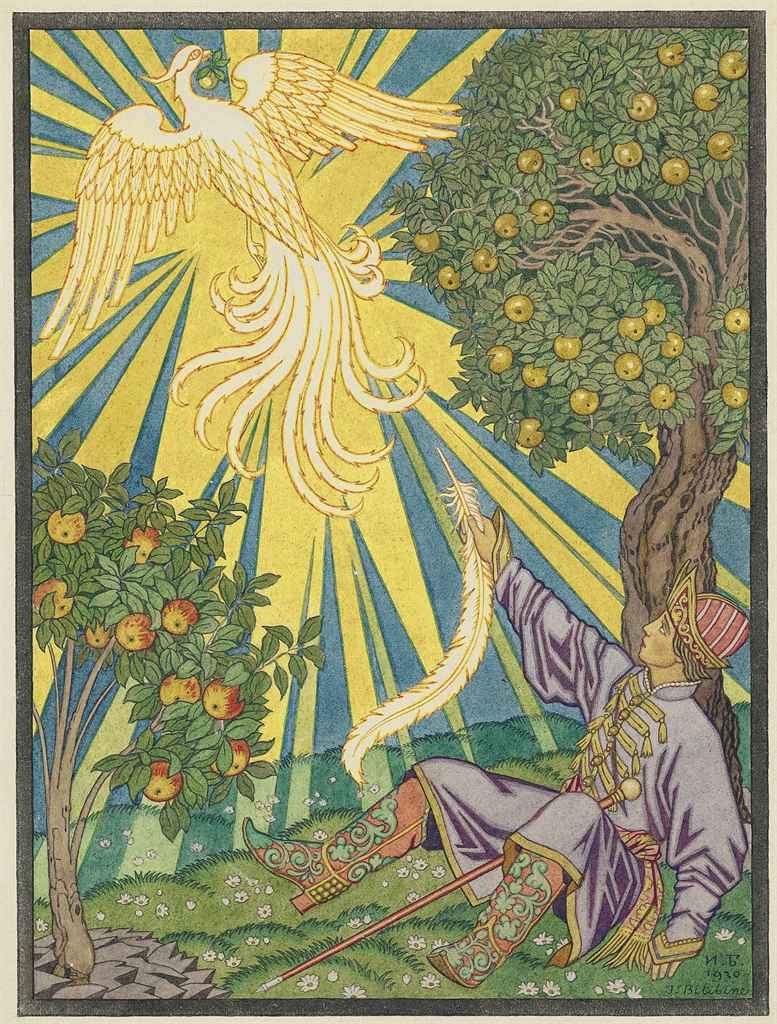

The firebird in Russian folklore was a magnificently coloured bird with magical powers; while it could be a protective and benevolent force, the firebird could also be a portend of doom. The artist Ivan Biliban creates a scene from one of the fairy tales about Prince Ivan and the Firebird. In his painting, the firebird is shown stealing one of the golden apples from the King’s orchard. Ivan, the king’s youngest son, tries to catch the firebird but only manages to pull one of his feathers.

To read the complete story about the prince and the firebird please open the link to the Project Gutenberg eBook here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/25513/pg25513-images.html).

For more information about Fenghuang, the Chinese mythical bird, please open the link here: Fenghuang | Phoenix, Bird-Woman & Immortality | Britannica

To view more folk and fairytale books that are illustrated by Edmund Dulac, please visit the websites below.

Type your textbox content here.

***************************************************************************

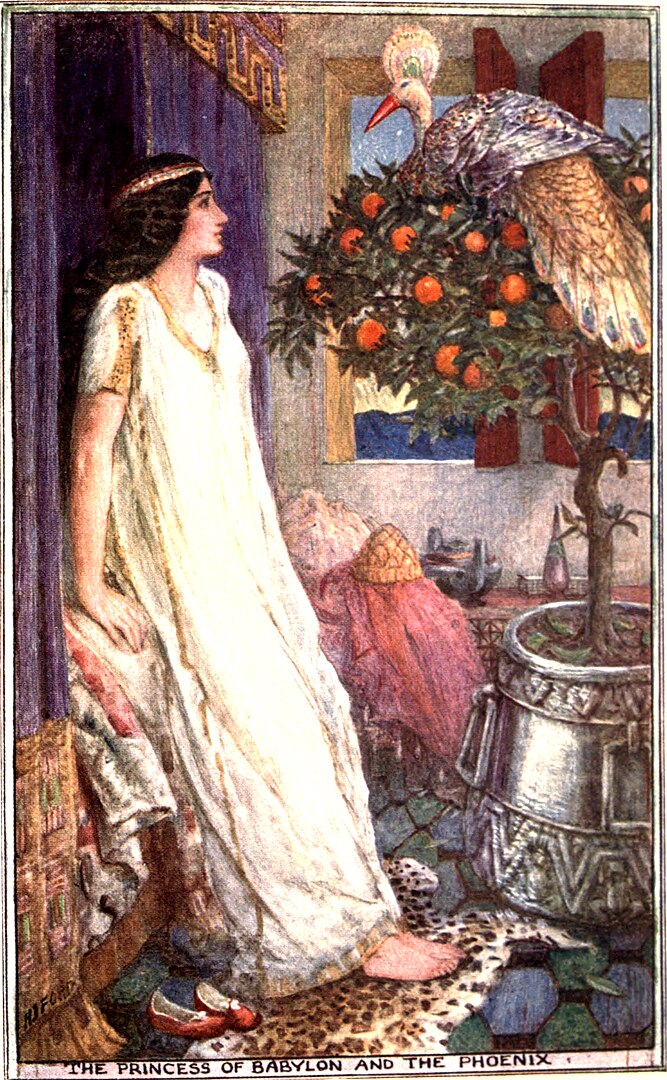

The following excerpt is from the story “The Princess of Bablyon and the Phoenix Bird.” The artist Henry Justice Ford’s painting is based on this scene from the story:

Everyone was glad to go to bed early after the fatigues of the day, and all slept soundly, except Formosante. She had carried the bird with her, and placed him on an orange-tree which stood on a silver tub in her room, and bidden him good-night. But tired as she was she could not close her eyes, for the scenes she had witnessed in the arena passed one by one before her. At length she could bear it no longer:

‘He will never come back! Never!’ she cried, sobbing.

‘Yes, he will, Princess,’ answered the bird from the orange-tree. ‘Who, that has once seen you, could live without seeing you again?’

Formosante was so astonished to hear the bird speak—and in the very best Chaldæan—that she ceased weeping and drew the curtains.

‘Are you a magician or one of the gods in the shape of a bird?’ asked she. ‘Oh! if you are more than man, send him back to me!’

‘I am only the bird I seem,’ answered the voice; ‘but I was born in the days when birds and beasts of all sorts talked familiarly with men. I held my peace before the court because I feared they would take me for a magician.’

‘But how old are you?’ she inquired in amazement.

‘Twenty-seven thousand nine hundred years and six months,’ replied the bird. ‘Exactly the same age as the change that takes place in the heavens known as the “precession of the equinoxes,” but there are many creatures now existing on the earth far older than I. It is about twenty-two thousand years since I learned Chaldæan. I have always had a taste for it. But in this part of the world the other animals gave up speaking when men formed the habit of eating them….” (pp. 239-240).

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Strange Story Book, by Mrs. Lang.

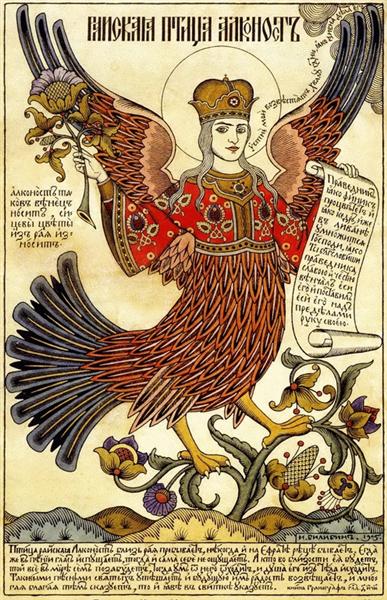

While different versions of Alkonosts surface in the mythology of Greek and Persian cultures, in Russian folklore the Sirin and Alkonost were mythological beings that were part woman and part bird (often an owl). Some folklorists suggests that 8th or 9th century Persian folktales were early sources for the Alkonost in Russian culture. The beautiful singing of the Alkonost was said to make people forget their worries and hardships. Links between the Alkonosts and stories of creation are also found. Thunderstorms were said to be caused with the Alkonost’s egges were hatched. These bird-women were thought to possess magical powers that impacted fruit and other crops to flourish. Exploration and inter-cultural travel resulted in numerous similarities between cultures and their depiction of Alkonosts. The Alkonost bird in Russian folklore was often associated with beauty, hope, wisdom, and happiness.

For more information please open the link below.

For the complete Japanese Fairy by Grace James and illustrations by Warwick Goble, please open the link below. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/35853/35853-h/35853-h.htm

By Warwick Goble – Green Willow and Other Japanese Fairy Tales, 1910 (https://archive.org/stream/greenwillowother00jame#page/n11/mode/2up), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41149691

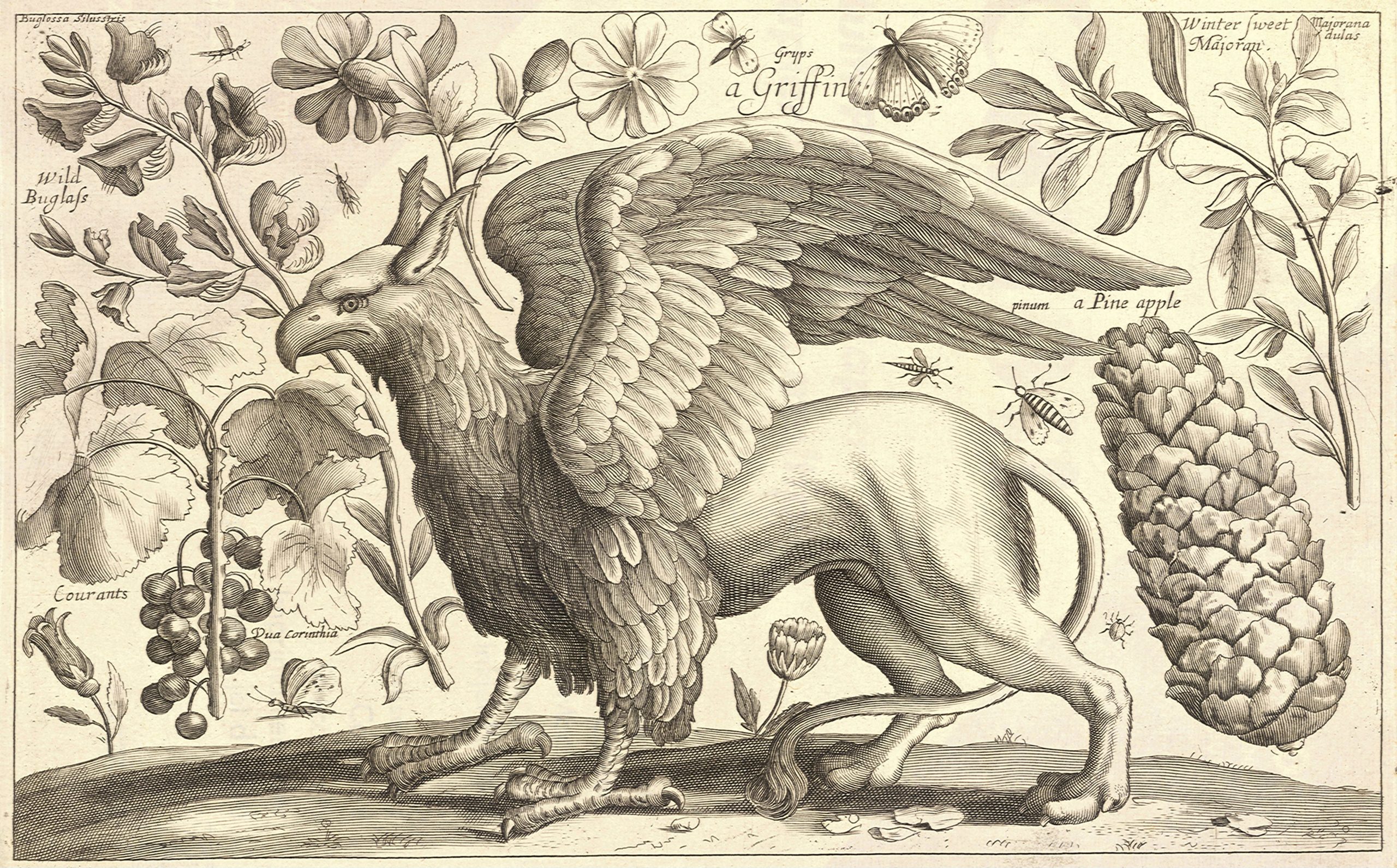

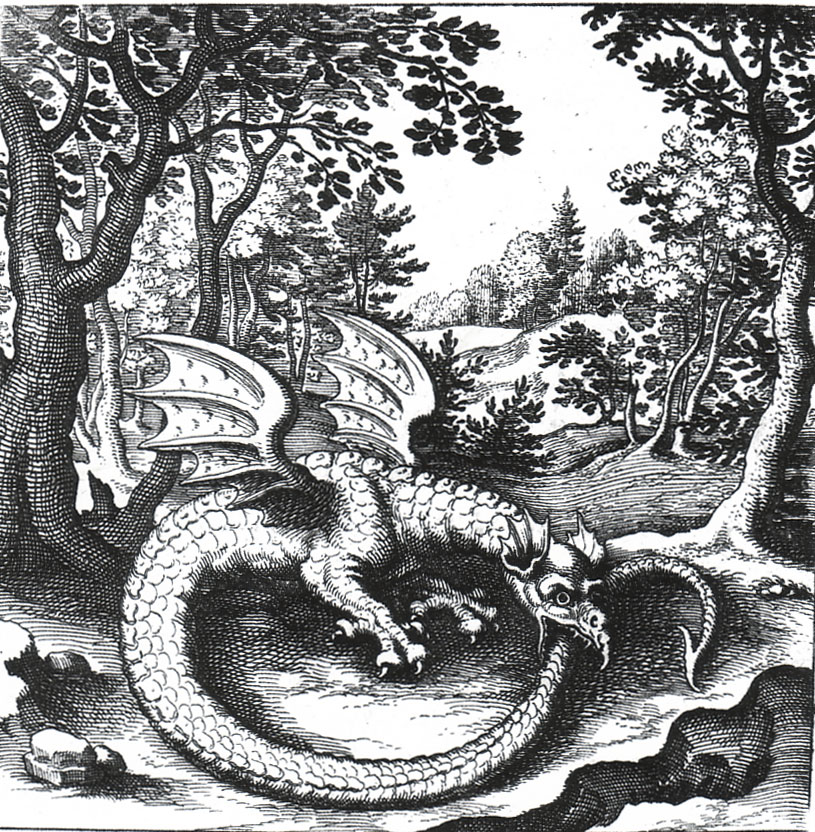

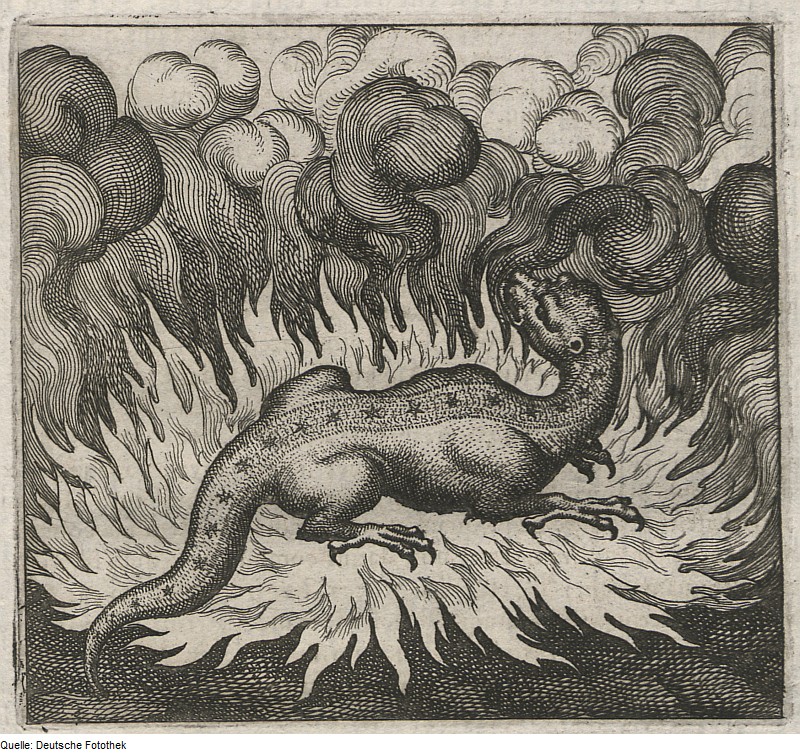

Engravings of Dragons and Winged Creatures

The Griffin (Ancient Greek: Γρύψ Grū́ps) is a legendary creature from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian, Minoan, Greek, and Roman mythology that has the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle.

Wyverns

The Wyvern is the symbolic mythological dragon/swan of Leicester, England. Wyvern are mythological creatures that have two legs and the body of a swan, snake, or fish. They are often seen as messages of good fortune.

For more information on the engravings and etchings of Lucas Jennis please open the link below.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Lucas_Jennis

Wikimedia and Duetsche Fototek (file donated to the Public Domain)

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/70/Fotothek_df_tg_0008188_Theosophie_%5E_Alchemie.jpg

“With their hardened beaks and talons and their poisonous droppings, the harpies were formidable monsters.” -Wilkinson et al. 2021, p.72.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7477/7477-h/7477-h.htm

The Project Gutenberg ebook of “The Book of Wonder,” by Edward J.M. D. Plunkett, Lord Dunsany.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7477/7477-h/7477-h.htm

For more information about the artist and illustrator Ivan Bilibin, please open (or insert in search) the link below.

https://www.wikiart.org/en/ivan-bilibin

The importance of the neglected art of storytelling and folklore that can inform our experiences in the present.

Preface from Tales from the Russian (1979) (originally published in 1903).

“In Russia, as elsewhere in the world, folklore is rapidly scattering before the practical spirit of modern progress. The traveling peasant bard or story teller, and the devoted “nyanya“, the beloved nurse of many a generation, are rapidly dying out, and with them the tales and legends, the last echoes of the nation’s early joys and sufferings, hopes and fears, are passing away. The student of folk-lore knows that the time has come when haste is needed to catch these vanishing songs of the nation’s youth and to preserve them for the delight of future generations. In sending forth the stories in the present volume, all of which are here set down in print for the first time, it is my hope that they may enable American children to share with the children of Russia the pleasure of glancing into the magic world of the old Slavic nation.” –Verra Xenophontovna Kalamatiano De Blumenthal.

Tales from the Russian. 1903. Retold by Verra Xenophontovna Kalamatiano De Blumenthal. Core Collection Books, 1979. Boise State University Library.

To read the complete collection of Russian Folktales, please open the link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12851/12851-h/12851-h.htm

The Neglected Art of Storytelling and the Importance of Folktales

In his introduction to Russian Folktales, Leonard Magnus explains that the songs, ballads, and folktales of Russia “mirrored life” which too often was tragic and difficult. He states among the peasant folk of Russian, a rich source of oral storytelling, songs, and ballads reflected the beliefs, values, and hopes of many. Magnus writes:

The principal source for Russian folk-tales is the great collection of Afanáśev, a coeval of Rybnikov, Kirěyevski, Sakharov, Bezsonov, and others who from about 1850 to 1870 laboriously took down from the lips of the peasants of all parts of Russia what they could of the endless store of traditional song, ballad, and folk-tale. These great collectors were actuated only by the desire for accuracy; they appended laboriously erudite notes; but they were not literary men and did not sophisticate, or improve on their material.

But, before venturing on a brief account of the tales, something must be premised as to the position occupied by folk-tales in the cultural development of a people. In Pagan times, there always existed a double religion, the ceremonial worship of the gods of nature and the tribal deities,—a realm of thought in which all current philosophy and idealism entered into a set form that symbolized the State,—and also local cults and superstitions, the adoration of the spirits of streams, wells, hills, etc. To all Aryan peoples, Nature has always been alive, but never universalized, or romanticized, as in modern days; wherever you were, the brook, the wind, the knoll, the stream were all inhabited by agencies, viwhich could be propitiated, cajoled, threatened, but, under all conditions, were personal forces, who could not be disregarded.

When Christianity transformed the face of the world, it necessarily left much below the surface unaffected. The great national divinities were proscribed and submerged; some of their features reappearing in the legendary feats of the saints. The local cults continued, with this difference, that they were now condemned by the Church and became clandestine magic; or else they were adopted by the Church, and the rites and sanctuaries transferred. The memory of them subsisted; the fear of these local gods degenerated into superstition; the magic of the folk-tales becomes half-fantastic, half-conventional, belief in which is surreptitious, usual, and optional. At this stage of disorganization of local custom, folk-tales arise, and into them, transmitted as they are orally and under the ban of the Church, contaminations of all sorts creep, such as mistaken etymologies, faint memories of real history, reminiscences of lost folk-songs, Christian legend and morals, etc.

The Russian people have handed down three categories of records. First of all, the Chronicles, which are very full, very accurate, and, within the limits of the temporary concepts of possibility and science, absolutely true. Secondly, the ballads or bylíny; epic songs in an ancient metre, narrating historical episodes as they occur; and also comprising a cycle of heroic romance, comparable with the chansons de geste of Charlemagne, the cycles of Finn and Cuchúlain of the Irish, and possibly with the little minor epics out of which it is supposed that some supreme Greek genius built up the artistic epics of the Iliad and the Odyssey. These bylíny may be ranked as fiction: i.e. as facts of real life (as then understood), applied to non-existent, unvouched, or legendary individuals. They are not bare records of viifact, like the Chronicles; imagination enters into their scope; non-human, miraculous incidents are allowable; their content is not a matter for faith or factual record; they may be called historical fiction, which, broadly taken, corresponded to actual events, and typified the national strivings and ideals. The traditional ceremonial songs, magical incantations and popular melodies are of the same date and in the same style.”-Leonard Arthur Magnus, 1915, p. 1-2. (1879-1924). Russian Folktales. Retrieved: September 17, 2022. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/62509/62509-h/62509-h.htm

Author: A. N., (Aleksandr Nikolaevich), (1826-1871) Afanasev(1826-1871)

*Slavic Folklore: Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Serbia, Bohemia, and other Slavic countries draw upon ballads, oral storytelling, and traditional poetry and verse contribute to the unique and mesmerizing stories. There are varied interpretation and translations to account for the differences in the stories.

Translator: Leonard Arthur Magnus (1879-1924)

-Leonard Magnus, Introduction to Russian Tales, p. 1-2.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/62509/62509-h/62509-h.htm

Project Gutenberg eBook of Russian Fairy Tales by W.R.S.Ralston.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22373/22373-h/22373-h.htm

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/39/Lubok_alkonost.JPG

Magic Horses and other Supernatural Creatures

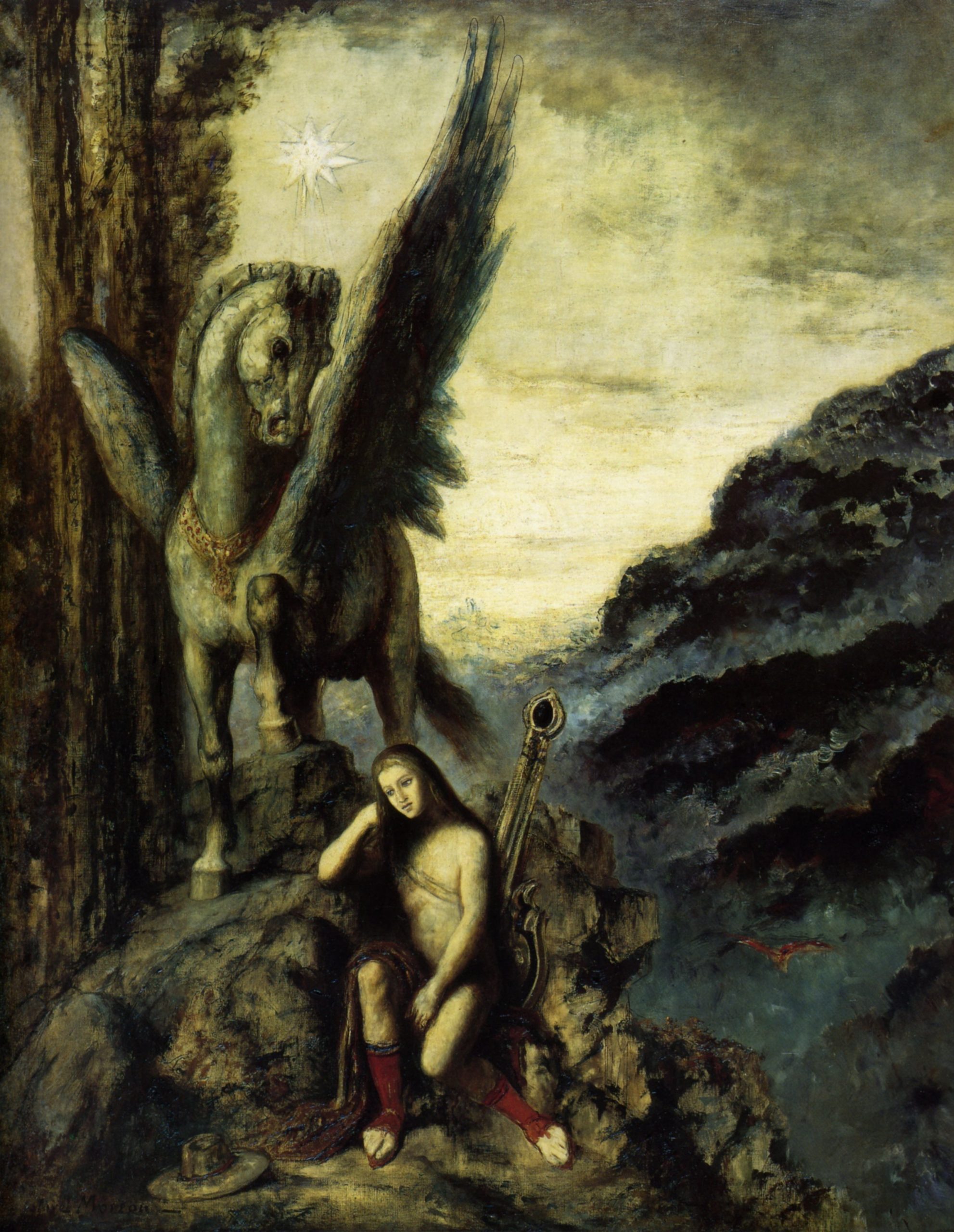

Pegasus in Art and Myth

Pegasus is the famous mythological horse often depicted as a powerful white stallion with enormous wings. He was the offspring of the Gorgon Medusa a monster that could turn men into stone with one look. Pegasus had a “twin” brother (Chrysaor) who is depicted as human. Pegasus had many supernatural powers; he could traverse the realms of the underworld of Hades, the earth, and the cosmos. His ability to transition from mortal to immortal realms made him invaluable to heroes like Bellerophontes (Bellerophon)who was able to tame him. With Pegasus he rode into battle to kill the chimera with a lead-tipped spear. Madeline Miller (2012) writes: “If ever a horse deserved gilded tack, it’s Pegasus. With it, Bellerophon was able to successfully tame him, and the two flew off to do battle with the Chimera. But because of the fire-breathing, Bellerophon and Pegasus couldn’t get close enough to the monster to stab it. So Bellerophon attached a piece of lead to his spear, then rammed it into the Chimera’s mouth on his next fly-by (Miller, 2012): https://madelinemiller.com/myth-of-the-week-pegasus-and-bellerophon/

Madeline Miller Retelling the Story of Pegasus:

https://madelinemiller.com/myth-of-the-week-pegasus-and-bellerophon/

(Bellerophon)

For more mythic illustrations of Walter Crane in The Wonder Book for Girls and Boys written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, please open the Project Gutenberg copy below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32242/32242-h/32242-h.htm

Blanche Ostertag, Illustration: For the complete illustrated version of myths every child should know by Mabie Hamilton Wright.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/16537/16537-h/16537-h.htm

Chimera: A Mythic Creature of Fantasy and Illusion

Chimera:

In Greek mythology, the Chimera was often depicted as a fire-breathing female monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and the tail of a serpent. Gustave Moreau was a major figure in the French Symbolist movement; with imaginative flair, Moreau depicted biblical and mythological figures and scenes. He was influenced by the Italian Renaissance and his paintings often feature rich detail, exotic landscapes, and powerful expression. Moreau’s chimera has a unique constellation of a horse’s body, a human face, and wings. “The term “chimera” has come to describe any mythical or fictional creature with parts taken from various animals, to describe anything composed of disparate parts or perceived as wildly imaginative, implausible, or dazzling.” (Retrieved March 26, 2023 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimera_(mythology) )

“As he descended, the daylight in which hitherto he

had been travelling faded from view.”

Stories from the Arabian Nights by Edmund Dulac and Retold by Housman (p. 141). Hodder & Stoughton, 1907.

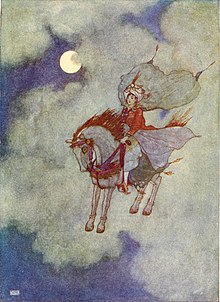

Ivan and the magical Chesnut Horse

With one spring Ivan was astride the chestnut horse, and, in another moment, they were speeding like lightning towards the shrine of Helena the Fair.

“The sun was setting, and the two elder brothers, disconsolate, were about to withdraw from the field, when, startled by the cries of the people, they saw a steed come galloping on, well ridden, and at a terrific pace. They turned to look and they marked how Helena the Fair, disappointed of all others, leaned out to watch the oncoming horseman. And the whole concourse turned and stood to await the possible event….On came the chestnut horse, his nostrils snorting fire, his hoofs shaking the earth. He neared the shrine, and, to a masterful rein, rose at a flying leap. The daring rider looked up and the Princess leaned down, but he could not reach her lips, ready as they were. The whole field now stood at gaze as the chestnut horse with its rider circled round and came up again. And this time, with a splendid leap, the brave steed bore its rider aloft so that the fragrant breath of the Princess seemed to meet his nostrils, and yet his lips did not meet hers (pp. 70-.71).

Project Gutenberg eBook of Edmund Dulac’s Fairy Tales of the Allied Nations. George H. Doran Co. New York. Project Gutenberg. 1917. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25513/25513-h/25513-h.htm