7 Nordic Myths, Legends, and Folklore: Art, Poetry, and Prose

Nordic Myths, Legends, and Folklore: Art, Poetry, and Prose

Courtesy: By Robert Wilhelm Ekman – http://kokoelmat.fng.fi/app?si=A+II+1256, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66322449

Ilmatar: Goddess of the Sea/Creation Goddess

Courtesy: Finnish National Gallery (open access) and Wikimedia

“The goddess Ilmatar lay down on the sea, heavily pregnant but bemoaning that she could not yet give birth. There, a bird laid seven eggs on her knees, and when she moved, the eggs fell and broke, and the pieces formed the world. For a time, Ilmatar was preoccupied with her creations but after 700 yeas of pregnancy, she gave birth to the first man: the fully formed Vainamoinen. Old and wise from birth, the hero is usually depicted with white hair and a beard.” (Wilkinson et al. pp. 161-162).

The Kalevala: Finland’s National Epic Poem

In the Finnish Folklore compilation of Poems called the Kalevala (Elias Lonnrot, 1888), themes of creation, heroism, magic, survival, violence, and death are described. Lonnrot’s compilation of folklore created a distinctive Finnish epic in the 1880s. This was a time when the Finnish culture, language, and identity were under threat from Russia. Similar in some ways to the tales of Ulysses, the Kaleva follows the adventures of Ilmarinen and the warrior Lemminkainen. More recently, Kirsti Makinen and Pirkko-Liisa Surojegin (2001) published a beautifully illustrated version of the Kalevala: Myths and Legends from Finland (Floris Books).

To read the poems in The Kalevala, please open the link below.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Kalevala: the Epic Poem of Finland, by Elias Lönnrot

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5186/5186-h/5186-h.htm

Icelandic Influences on Nordic Myths and Legends: Snorri Sturleson’s Prose Edda in words and image

Time Line of Norse Mythology

The Greek myths predate the Norse myths which developed during the time of the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE). Similar Indo-European themes emerge in Norse myths; in addition, early Christian influences in Viking Europe influenced the way the oral tales were told throughout the ages. Wilkinson et al. (2021) explain that the regional diversity of Norse myths can be traced back to the fact that before they became Christian, the peoples of northern Europe were primarily divided into tribes and chiefdoms. Celtic and Christian influences on the Norse myths can be traced back to the 5th century. Linguistic and cultural exchanges through trade and travel generated similar themes in myths among Greek and Roman, Asian, Middle Eastern, Indigenous, and Norse Myths.

Some of the best known myths and legends from northern Europe are set, and probably originated, in the years after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE. The earliest legends of King Arthur, for example, presented him as a heroic warlord defending the Celtic Britons against the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, who invaded Britain after the withdrawal of Roman forces in 400 CE. After the Norman conquest in 1066, Arthur was appropriated by French and English writers who depicted him as an idealized and chivalric king of all England. Poetic material that is very rich is found in Snorri Sturluson’s work on Old Norse poetics, entitled The Edda, and often referred to as the The Younger Prose Edda. The sagas integrate both myth and history.

The appeal of the Norse and Celtic legends, with their tales of heroes and dragon-slayers, remains strong in the modern world. They have inspired many works of art, music, and literature, from Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Arthurian tales to Richard Wagner’s The Ring of Nibelung operas and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (Wilkinson et al, 2021, p. 129).

Norse Mythology Time Line:

Norse Mythology Timeline – World History Encyclopedia

Additional Reference:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/65910/65910-h/65910-h.htm

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Norse mythology; or The religion of our forefathers, containing all the myths of the Eddas, compiled and interpreted, by Rasmus Björn Anderson (1846-1936). Published by S. C. Griggs & Co. /London Trubner & Co. Chicago, 1876.

Courtesy: By Edward Burne-Jones – EAEbUcHZ0dEuvg at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21997518

Additional Links:

There are many artistic rendering of St. George and the Dragon. It is important to note that while in some renderings the dragon symbolizes a force of evil and destruction, other cultures (most notably in Asia) feature the dragon as a protective force of strength and wisdom (see Fantastic Creatures sections, “In the Air” Book One).

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Melbourne, Australia:

The fight: St George kills the dragon VI, 1866 by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Melbourne, Australia. NSW https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/8536/

The Prose Edda (the Younger Edda) by Snorri Sturleson (13th Century Icelandic Chieftan and Poet).

The Prose Edda (also known as the Younger Edda) was written by the Icelandic Chieftain and Viking scholar Snorri Sturleson in the 13th century (c. 1220). Sturluson brought together the myth, skaldic poetry, stories, and history of the Viking age (800-1100) in what is considered one of the greatest and most well-known compilations of ancient Norse myths, sagas, and legends (Byock, 2005). The Viking era was a time when Scandanavian adventurers and seafarers explored, raided, and settled far reaching lands. The stories shared were influenced from such travels and encounters with other cultures. Rasmus B. Anderson and Helen Guerber were among a number of notable writers and folklorists that translated the eddas and sagas. Excerpts from their 19th century translations can be found throughout the chapter section.

Excerpt from Snorri Sturluson (13th Century). The Prose Edda. Translated with an introduction and notes by Jesse L. Byock. Penguin Books. 2005

Modern translations of The Prose Edda and related sagas help to interpret the scope of the Nordic pantheon of gods and goddesses and the systems of beliefs and values that united people. Jesse Byock (2005) explains that before the conversion to Christianity, Viking Age Scandanavians did not have a unified religion; the myths, legend, and folklore revolving around the Norse pantheon of gods, mythical creatures, and fantastical happenings formed the world view of many Nordic people. Byock (2005) writes that:

“Geographical and political circumstances help to explain why the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda were written in the form they were in medieval Iceland. [Iceland] was an immigrant society formed by colonists from many parts of the Viking World, but especially from Norway and the Norse colonies in the British Isles. In a frontier setting on the far northern edge of he habitable world, the Icelanders held fast to the cultural memories brought by the early settlers, which provided them with a sense of common origin and helped bind them to a cohesive cultural group.” (Byock, 2005, p. x-xi). .

Drawing on oral tales passed down throughout the generations, The Prose Edda reflects an awareness of two Latin literary genres during the Middle Ages: mythological writing and language and poetics. The first part of the Edda (Prologue) elevates Norse mythology with Greek and Roman mythology; in addition, an effort to integrate elements of Christian concepts are highlighted. A large part of The Prose Edda describes the story of creation, the struggles and conflicts of the gods, the events leading to the twilight of the gods and the destruction of the universe, and the gradual resurrection of a new kingdom founded on peace. This section is in the form of a dialogue with King Gylfi of Sweden (disguised as a traveller) asking questions to the most powerful god-like (Aesir) figures such as Odin (Woton, King of the gods). “In the Aesir’s (gods) majestic but illusory hall, Gangleri/Gylfi meets three manifestations of Odin: High, Just-as-High, and Third. These strange, lordly individuals sit on thrones one above the other” (Byock, 2005, p.xv).

Other sections of the Edda describe well-known references, allusions, legendary heroes and folkloric tales found in Old Norse verse. The Prose Edda functioned like a contemporary text and resource book that helped Icelandic poets, readers, and scholars understand the Norse stories as well as the meaning and structure of skaldic poetry. Some of the selected art images in the following pages are complemented with corresponding verses & descriptions from The Prose Edda.

Project Gutenberg Books by Winifred Faraday, Norse Scholar.

The Edda, The Divine Mythology of the North by Winifred Faraday (1901)

Book One: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13007/13007-h/13007-h.htm

Book Two: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13008/13008-h/13008-h.htm

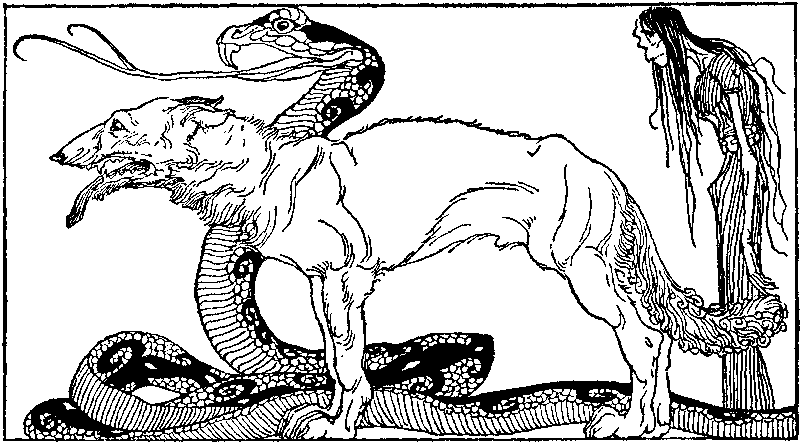

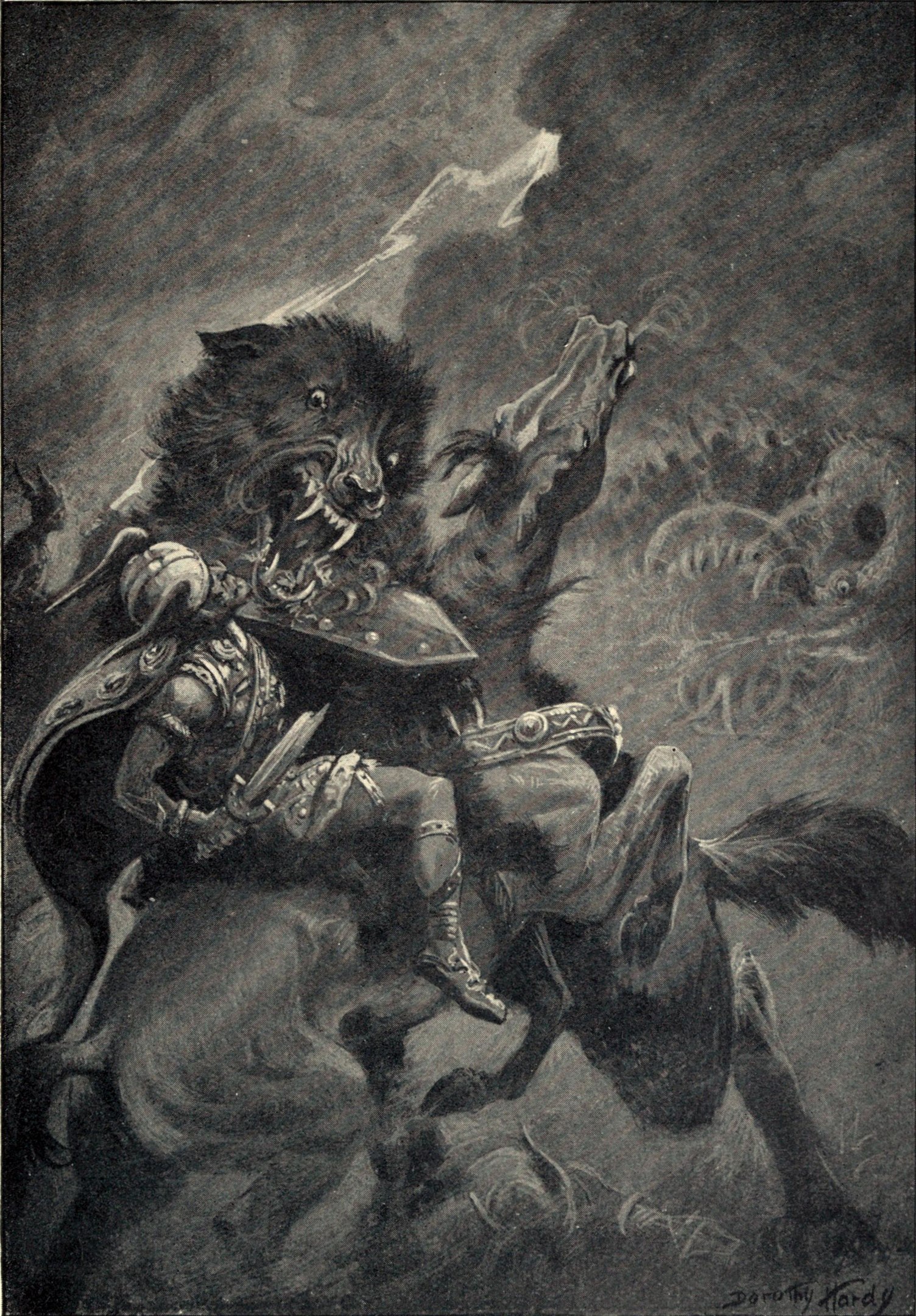

Siegfried and the Dragon

The Norse legend of the dragon-slaying hero Sigurd includes real historical figures, testifying to its origins in the 5th or 6th century.

J. Reich (1852-1923) and J. Gehrts (1833-1898). Illustration in Sarah Powers Bradish Old Norse Stories. American Book Co, 1900.

Old Norse stories (archive.org )https://ia800701.us.archive.org/26/items/oldnorsestories00brad/oldnorsestories00brad.pdf

http://ia601609.us.archive.org/25/items/oldnorsestories00bradgoog/oldnorsestories00bradgoog.pdf

Project Gutenberg eBook of Old Norse Stories

Illustration: Information and Library Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. University of North Carolonian. https://archive.org/details/oldnorsestories01bradgoog/page/n14/mode/2up

The Influence of Norse Literature on English Literature, by Conrad Hjalmar Nordby, 1901.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13786/13786-h/13786-h.htm

Norse World View

Old Norse Stories by Sarah Bradish Powers (1867-1922). American Book Company, 1900. Internet Archive eBook. Public Domain (Excerpt).

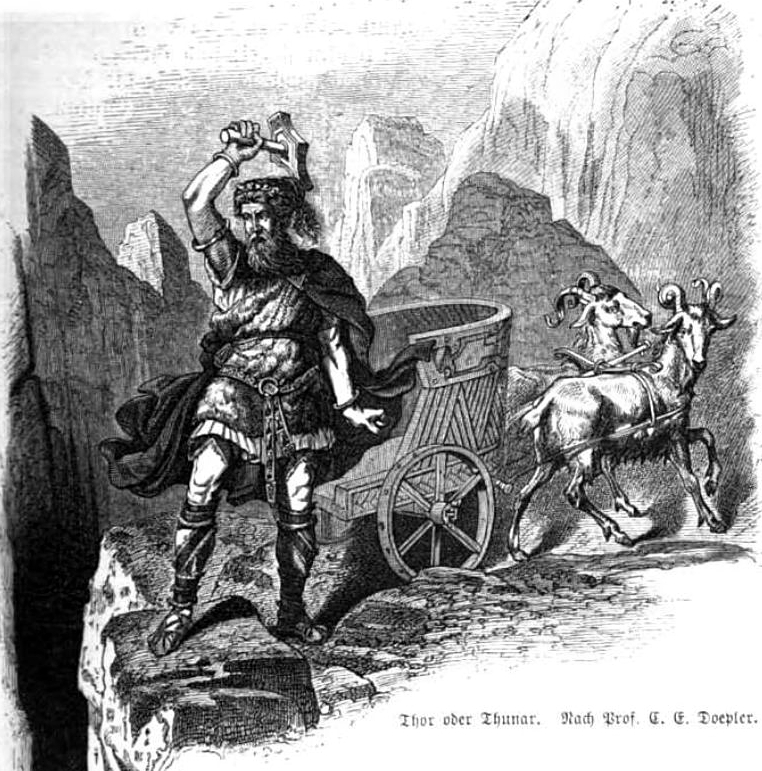

“Many years ago our forefathers, who lived far away in the Northland, thought that everything in the world was controlled by some god or goddess, who had special care of that thing. When spring came they said, ” Iduna is waking.” In early summer, when grass covered the hill- sides and grain waved in the valleys, they said, ” Sif is preparing a plentiful harvest.” When thunder clouds rolled across the sky and lightning flashed, they said, “Thor is driving his chariot and throwing his hammer.” They were glad when the long, light days of summer came, and said, “” We love Balder the beautiful, Balder the good.” But they shrank from the scorching heat of later summer, and said, “We fear the pranks of Loki, the mischief maker.” They saw the rainbow, and called it the bridge leading up to the home of the gods. They loved the gods who were kind to them ; and they dreaded the frost giants and storm giants, who were the enemies of gods and men. They prayed to Odin, the All-father, for wisdom andprotection, because they did not know the name of the one great God. When they gathered around the fireside in long winter evenings, they told tales of giants, dwarfs, and elves ; and

talked of Sigurd, the prince of the sunlight, who killed the dragon of cold and darkness and waked the dawn maiden. They thought much of the wonderful beings who lived, as they supposed, above the cloudor under the earth, and told many strange and beautiful stories…” (Sarah Bradish Powers, 1900, p. 1-2..https://ia800701.us.archive.org/26/items/oldnorsestories00brad/oldnorsestories00brad.pdf).

To read more of the Norse Myths please open the Internet Archive eBook of Sarah Bradish Powers (1867-1922). Old Norse stories. American Book Company, 1900 (please open link above or below for the full text).

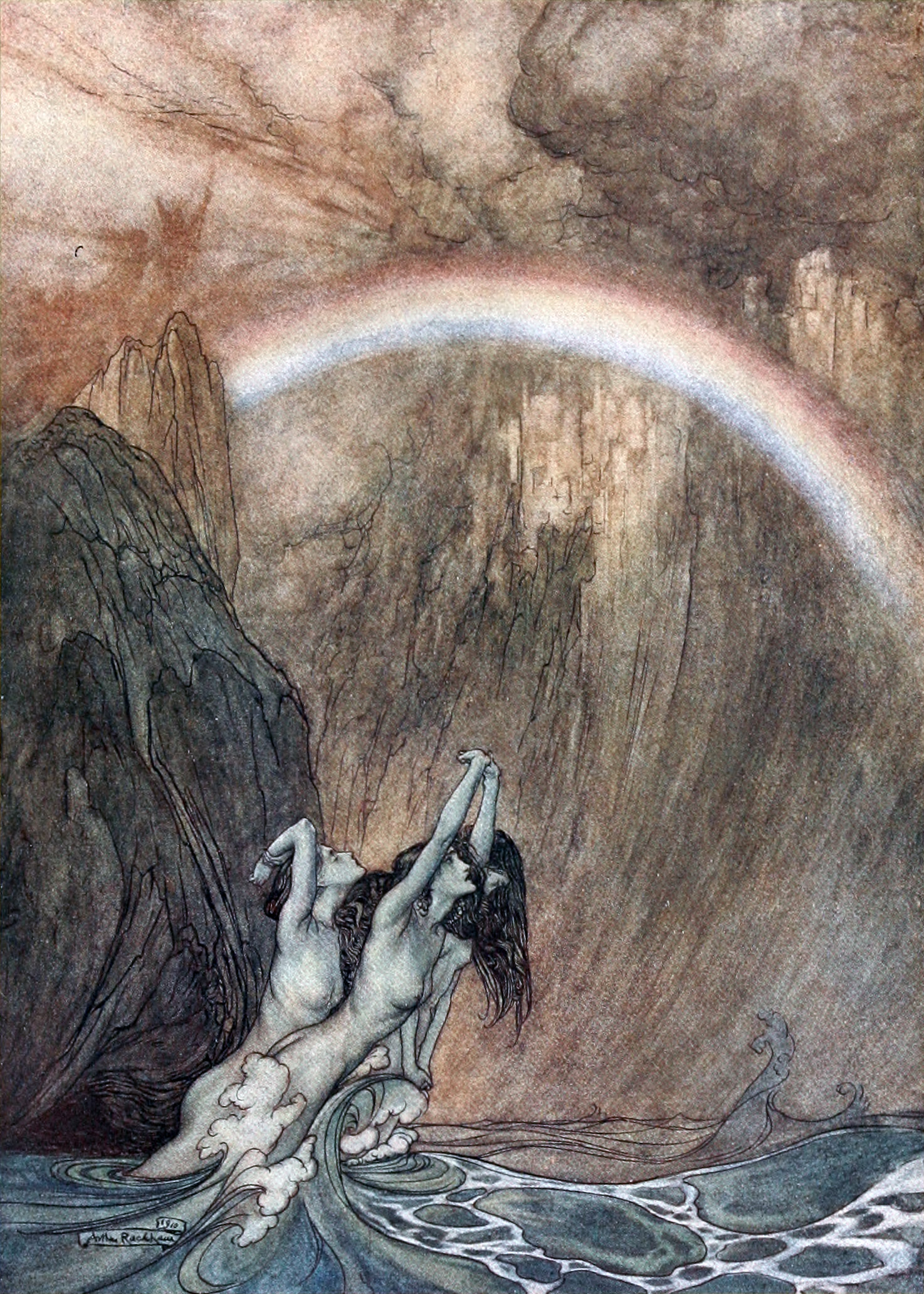

*These stories come beautifully illustrated. Artists such as Johannes Gehrts, Charles Dollman, Konrad Delitz, Arthur Rackham, Carl Emil Doepler and his son Emil Doepler visualized the myths with innovative etchings that inspire contemporary fantasy artists today. Artists creating the sets for films such as The Game of Thrones, House of Dragon, and the Lord of the Rings saga continue to draw inspiration from the works of earlier artists that visualized the incredible panoramic details in the original Nordic texts and their translations.

Old Norse Stories by Sarah Bradish Powers. Internet Archive. Public Domain.

Old Norse stories (archive.org)

https://ia800701.us.archive.org/26/items/oldnorsestories00brad/oldnorsestories00brad.pdf

Illustrations for R. Wagner’s Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods (Illustrated by Arthur Rackham).

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Siegfried_and_the_Twilight_of_the_Gods

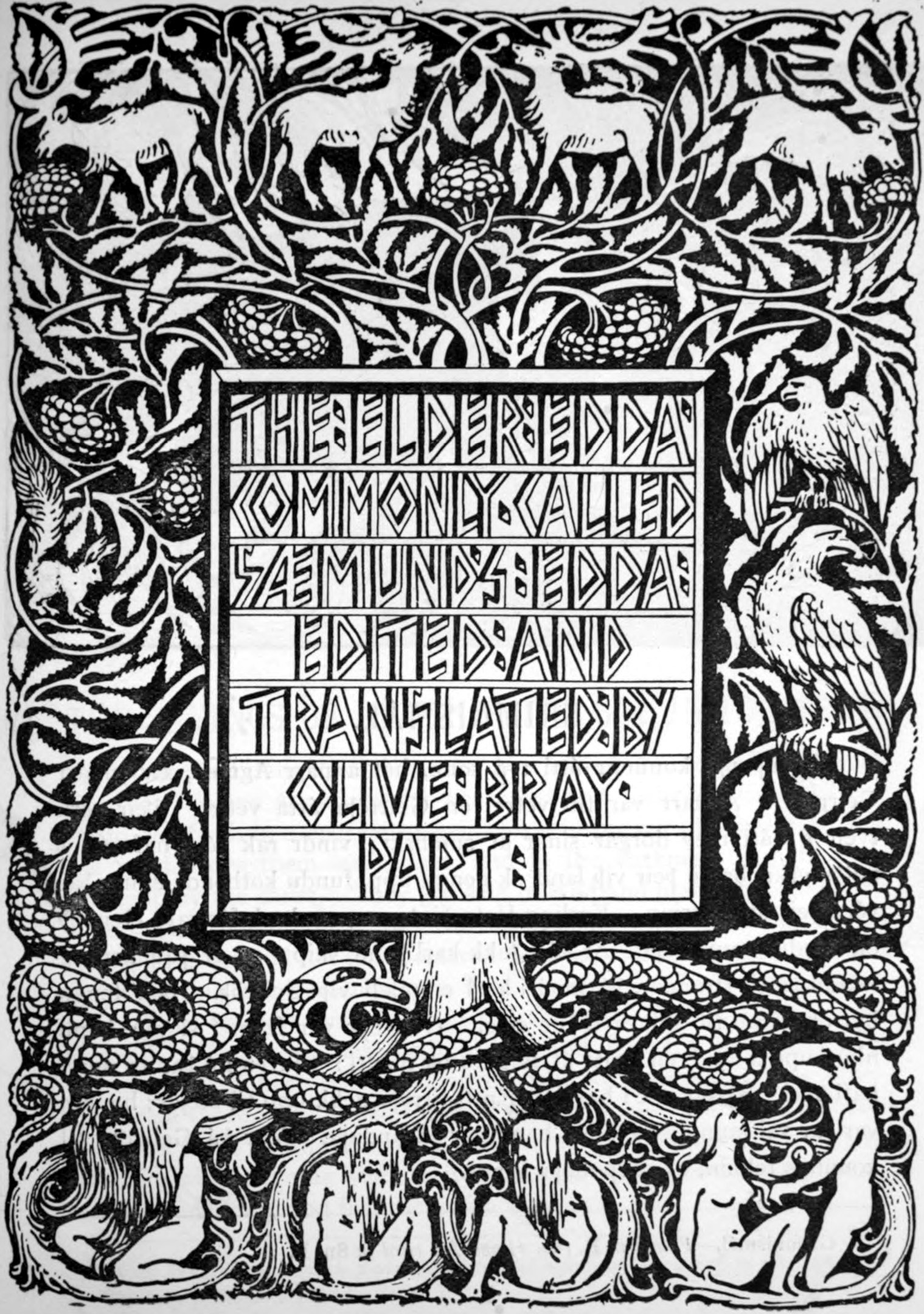

A translation of The Poetic Eddas by Olive Bray (1880-1937) and illustrated by W.G. Collingwood inspired R. J. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings.

The Divine Mythology of the North by Winifred Faraday. Published by David Nutt at the Sign of the Phoenix, Long Acre, London, England. 1902.

Project Gutenberg eBook

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13007/13007-h/13007-h.htm

*As you read the various translations of the Nordic myths, you may find some easier to understand than others.

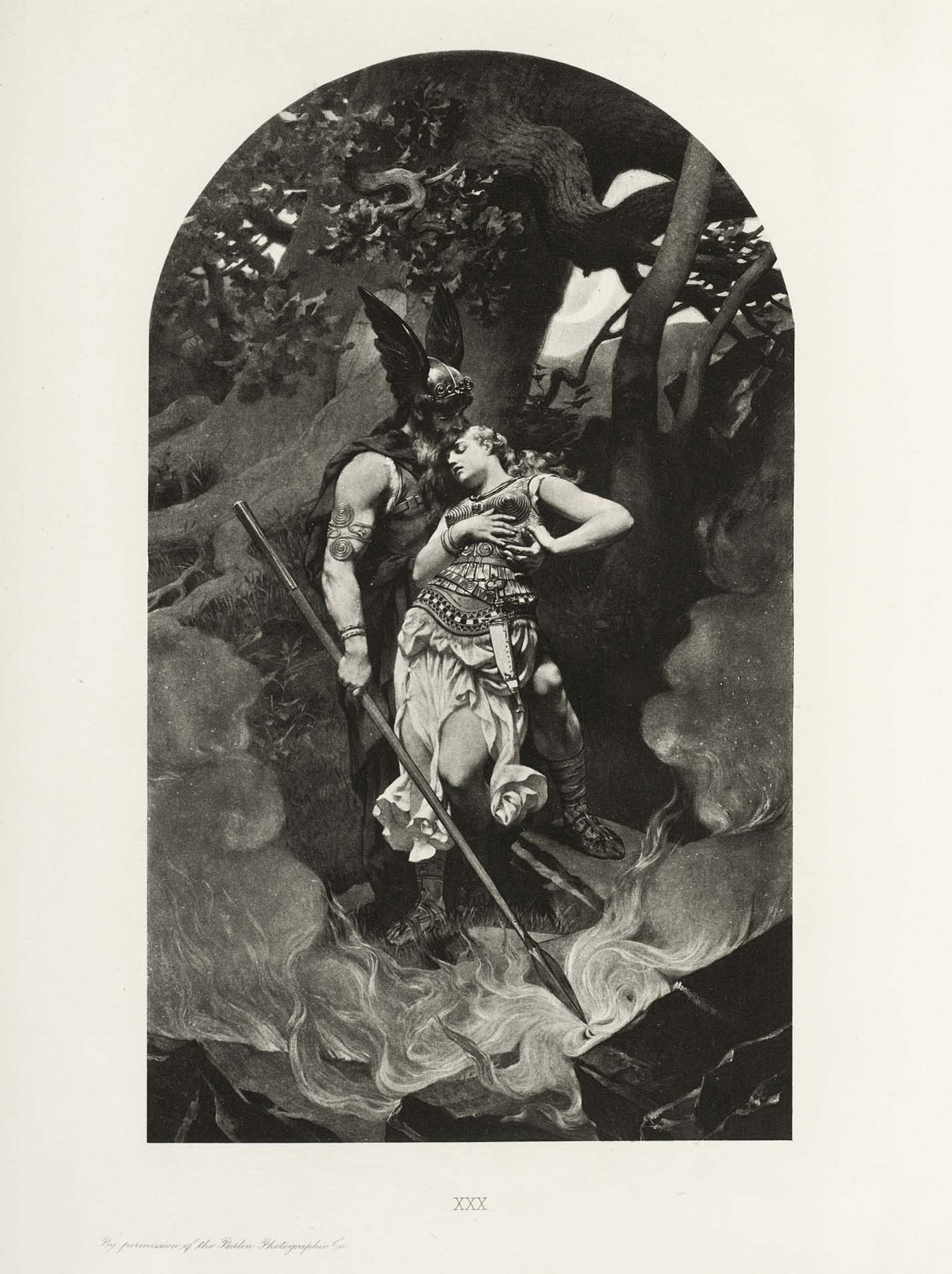

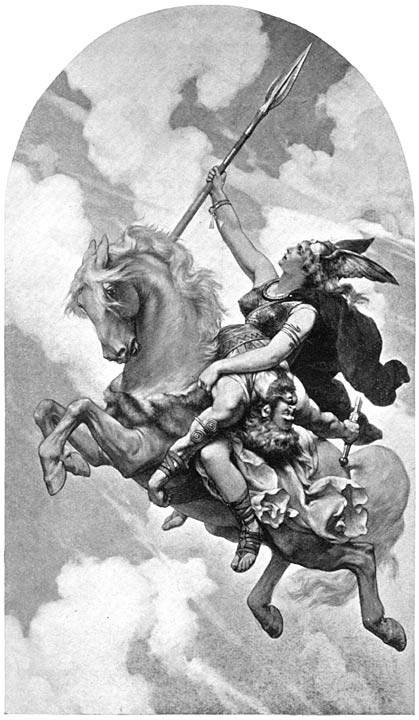

Courtesy: Wagner, Richard. (July 22, 2015). Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods: The Ring of the Niblung, A Trilogy with a Prelude. Project Gutenberg (Public Domain). Retrieved August 20, 2023, from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49507/49507-h/49507-h.htm#siegpl011

The Dramatic Landscape of Scandanavia: A Source of Inspiration for Story Tellers, Writers, and Artists

“The dramatic landscape of Scandanavia, with it electric skies, icy wastes and seething springs was easily people with nature spiritus. Such spirits roamed the mountains and snow slopes as fearsome frost, storm, and fire giants, personifying the mysterious and menacing forces of nature. So great were the terrors of crushing ice and searing fire that the giants loomed large in the Norse myths as evil and ominous forces” (Cotterell, 1996, p. 20).

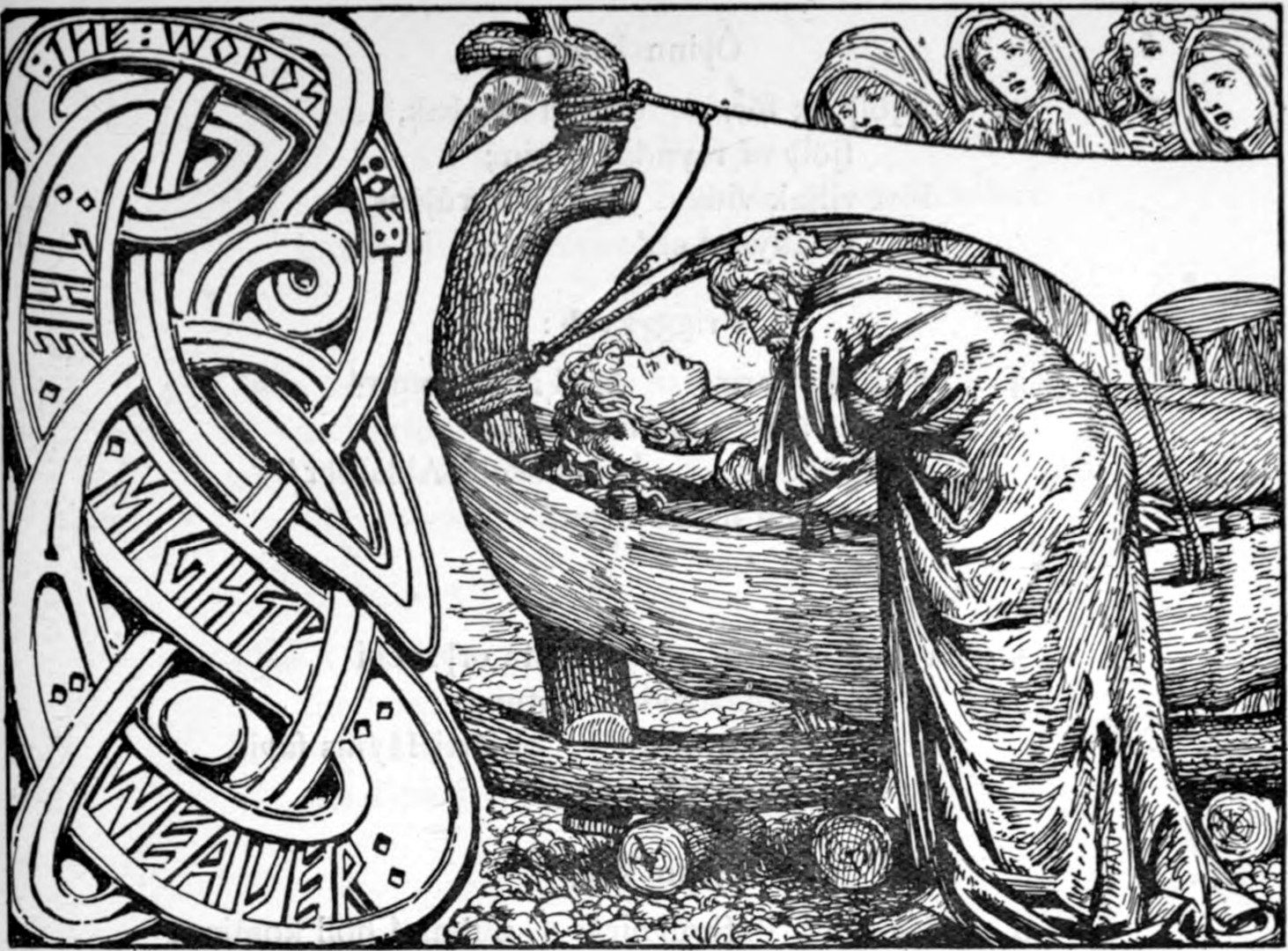

Nordic Stories of Creation

The Viking Age, as Jesse Byock (2005) writes, was a time where traditional storytelling was oral and usually conveyed in verse that was complex and intricate. A sign of intellect and learning, “Norse heroic and mythic poetry was also a word game whose intricate language paralleled the style of Viking Age carvings made on wood, stone, and metal objects” (p. 123). Wordsmiths and artisans created elaborate symbols to represent ideas and events.

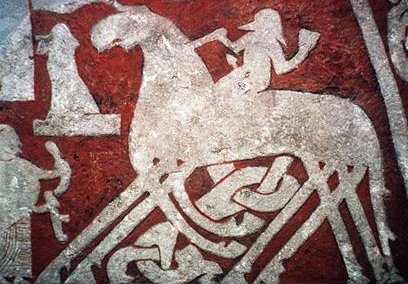

Courtesy: By Unknown author – en:Image:Ardre Odin Sleipnir.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34984

This runic stone/archaeological stone features Odin and his eight legged horse Sleipnir on the Tjangyide image stone in Valhalla. The stone may also depict a killed warrior on his way to Vallhalla greeted by the Valkyries with horn goblets in their hands. The Valkyries were the mythic maidens of war who protected the warriors and returned them to be reunited with Odin in Valhalla if they died.

*This is an art image of an archaeological site or monument in Sweden. The runic stones often depicted events from the Viking myths. Runic stones featured important historical details about the culture, families, and history of the Swedish people. Number cb884bf0-6941-497c-a2ef-5dc6cd5d12e0 in the RAÄ Fornsök datab.

Norse Myths of Creation

As indicated earlier, the major sources of the Norse myths came from Snorri Sturluson, a 13th century Icelandic poet and chieftan who transcribed and put into writing the great poetry and sagas. The Norse creation myths describe the first gods slaying the giant Ymir; his body parts formed different realms and regions of the world. The universal cosmic tree Yggdrasil identified the different earthly and heavenly realms as well as well as details about the underworld. The apocalyptic twilight of the gods or Ragnarok signified the end times but there was hope that a new world would be resurrected after Ragnarok. The Norse myths are complex, sweeping in their breadth and depth, and compelling; this section highlights a small selection of mythic images, poetry from The Prose Edda, and prose commentary. Links to teaching and learning resources on the Norse myths and legends are integrated throughout and at the end of this unit.

In Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas , H.A. Guerber (1909) wrote that “northern mythology is grand and tragical. Its principal theme is the perpetual struggle of the beneficent forces of Nature against the injurious forces, and hence it is not graceful and idyllic in character, like the religion of the sunny South, where the people could bask in perpetual sunshine, and the fruits of the earth grew ready to their hand.” (p. 9). While the Aesirs (gods) and Asynjurs (goddesses) were the first divinities worshipped, Northern peoples also recognized the powerful and divine forces of nature such as the wind, the sun, the moon, the sea, the forests, and animal and plant life. The gods resided in Asgard (home of the Gods) and Valhalla (a large hall where Odin (King of the Gods) resided.” (Retrieved July 18, 2023 Project Gutenberg ebook of Myths of the Norsemen by H.A. Guerber: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/28497/pg28497-images.html).

*Hélène Adeline Guerber (1859–1929) known H.A. Guerber, was an American writer. Her works include eloquent retellings of myths, legends, folklore, epic poetry, and history. To read more about her work, please access the link below.

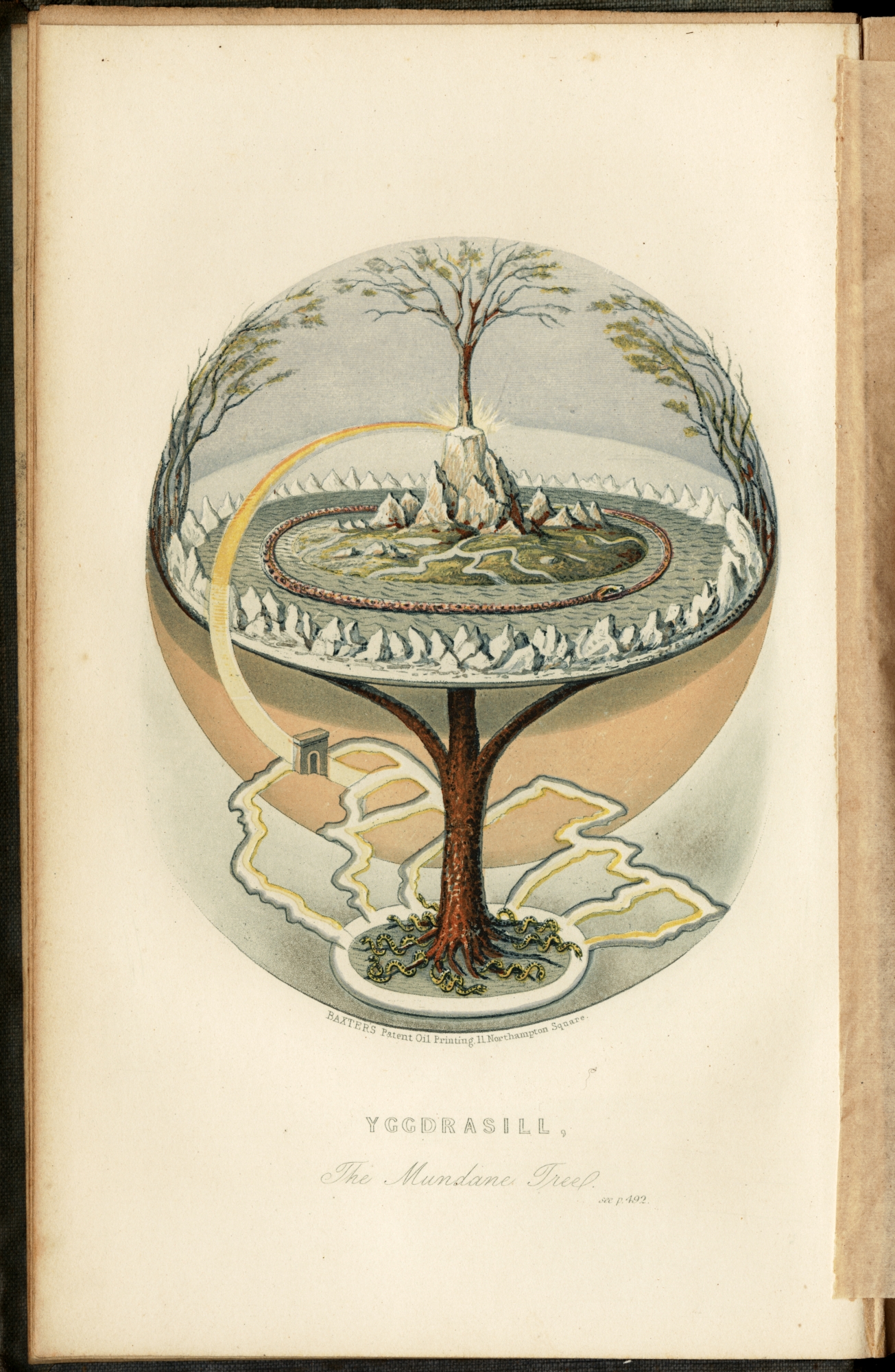

The Tree of Yggdrasil

Courtesy: By W.G. Collingwood (1854 – 1932) – The Elder or Poetic Edda; commonly known as Sæmund’s Edda. Edited and translated with introduction and notes by Olive Bray. Illustrated by W.G. Collingwood (1908) Page 1. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/elderorpoeticedd01brayuoft This image was made from the JPEG 2000 image of the relevant page via image processing (crop, rotate, color-levels, mode) with the GIMP by User:Haukurth. The image processing is probably not eligible for copyright but in case it is User:Haukurth releases his modified version into the public domain., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4657633

The Sacred Ash Tree

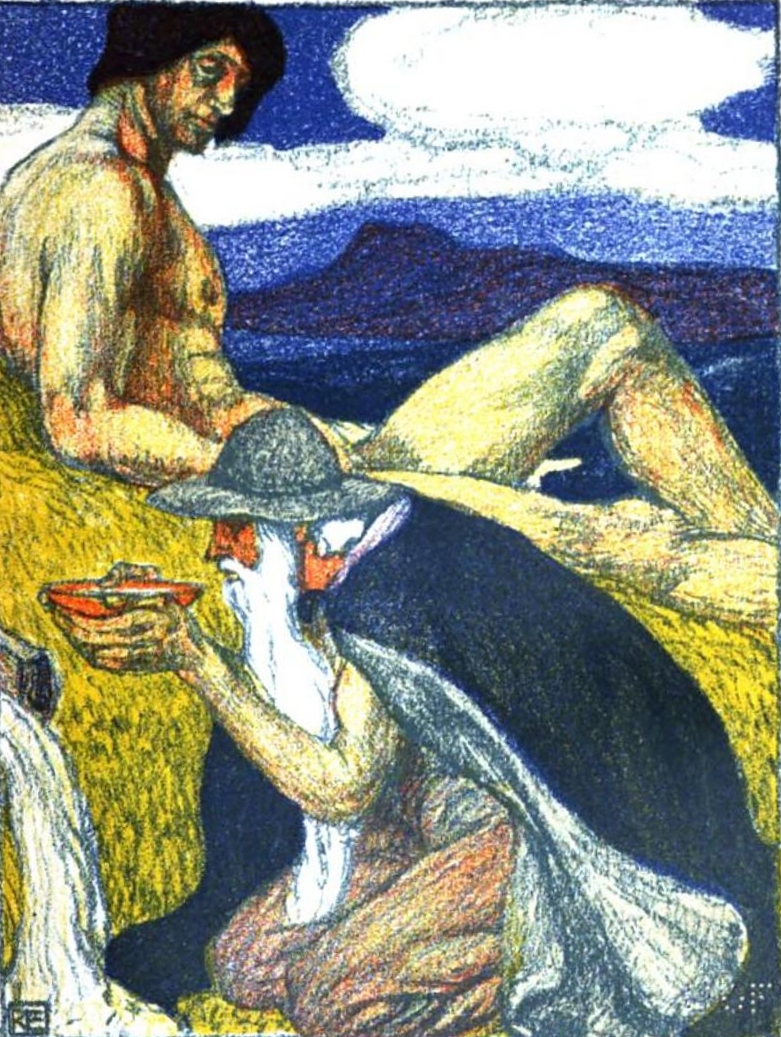

Then said Ganglere: Where is the chief or most holy place of the gods? Har answered: That is by the ash Ygdrasil. There the gods meet in council every day. Said Ganglere: What is said about this place? Answered Jafnhar: This ash is the best and greatest of all trees; its branches spread over all the world, and reach up above heaven. Three roots sustain the tree and stand wide apart; one root is with the asas and another with the frost-giants, where Ginungagap formerly was; the third reaches into Niflheim; under it is Hvergelmer, where Nidhug gnaws the root from below. But under the second root, which extends to the frost-giants, is the well of Mimer, wherein knowledge and wisdom are concealed. The owner of the well hight Mimer. He is full of wisdom, for he drinks from the well with the Gjallar-horn. Alfather once came there and asked for a drink from the well, but he did not get it before he left one of his eyes as a pledge. So it is said in the Vala’s Prophecy:

Well know I, Odin,

Where you hid your eye:

In the crystal-clear

Well of Mimer.

Mead drinks Mimer

Every morning

From Valfather’s pledge.

Know you yet or not?

The third root of the ash is in heaven, and beneath it is the most sacred fountain of Urd. Here the gods have their doomstead. The asas ride hither every day over Bifrost, which is also called Asa-bridge. The following are the names of the horses of the gods: Sleipner is the best one; he belongs to Odin, and he has eight feet. The second is Glad, the third Gyller, the fourth Gler, the fifth Skeidbrimer, the sixth Silfertop, the seventh Siner, the eighth Gisl, the ninth Falhofner, the tenth Gulltop, the eleventh Letfet. Balder’s horse was burned with him. Thor goes on foot to the doomstead, and wades the following rivers:

Kormt and Ormt

And the two Kerlaugs;

These shall Thor wade

Every day

When he goes to judge

Near the Ygdrasil ash;

For the Asa-bridge

Burns all ablaze,—

The holy waters roar.

The asked Ganglere: Does fire burn over Bifrost? Har answered: The red which you see in the rainbow is burning fire. The frost-giants and the mountain-giants would go up to heaven if Bifrost were passable for all who desired to go there. Many fair places there are in heaven, and they are all protected by a divine defense. There stands a beautiful hall near the fountain beneath the ash. Out of it come three maids, whose names are Urd, Verdande and Skuld. These maids shape the lives of men, and we call them norns. There are yet more norns, namely those who come to every man when he is born, to shape his life, and these are known to be of the race of gods; others, on the other hand, are of the race of elves, and yet others are of the race of dwarfs. As is here said:

Far asunder, I think,

The norns are born,

They are not of the same race.

Some are of the asas,

Some are of the elves,

Some are daughters of Dvalin.

Then said Ganglere: If the norns rule the fortunes of men, then they deal them out exceedingly unevenly. Some live a good life and are rich; some get neither wealth nor praise. Some have a long, others a short life. Har answered: Good norns and of good descent shape good lives, and when some men are weighed down with misfortune, the evil norns are the cause of it. ” (Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda. Translated by Rasmus Bjorn Anderson. Copryight 1879 by S. C. Griggs & Co. Press of the Henry O. Shepard Co. Chicago, Illinois. Project Gutenberg eBook: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/18947/pg18947-images.html#gylfe_VI. Public Domain).

https://myndir.uvic.ca/EldEdd-1908-001-TtPg.html

The tree Yggdrasill, complete with Ratatoskr, the four stags, Níðhöggr and Veðrfölnir. This is the title page of the book. The list of illustrations in the front matter of the book gives this one the title Title: The Tree of Yggdrasil.

Addional PD Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Haukurth

Resources on Norse Myths

Classic Texts about Norse Mythology from the 19th and early 20th Century:

Anderson, R.B. (1876). Norse Mythology of the Religion of Our Forefathers. S.G. Griggs & Co. 1876.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/65910/65910-h/65910-h.htm

Illustrated Versions of the Eddas

For the illustrated texts of the Prose Edda, please open the links to the Project Gutenberg below:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14726/14726-h/14726-h.htm

Bray, O. (1908). The Elder or Poetic Edda translated by Olive Bray, Viking.

Illustrated by W.G. Collingwood (1908) Page 1. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/elderorpoeticedd01brayuoft

Source: Haukurth & Wikimedia Commons.

Open Access Internet Library

https://archive.org/details/elderorpoeticedd01brayuoft/page/n5/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater

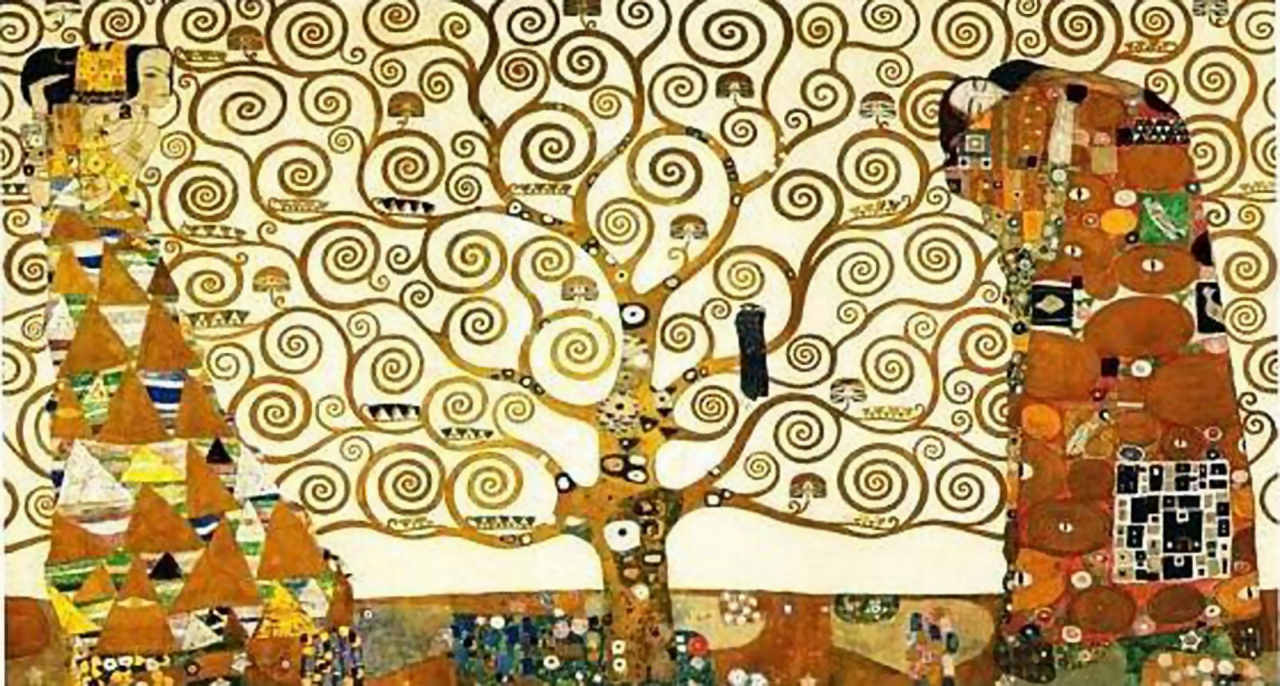

The Cosmic Tree of Life and Yggdrassil

From Ireland across to northern Europe throughout Central Asia and North America, the mythology of the cosmic world tree or tree of life that linked heaven, earth, and the realm of the underworld evolved. Diverse theologies, philosophies, myths, and legends include varied references to the tree of life. Trees represented a connection between the mortal and the divine and between heaven and earth. Trees were viewed as animate and sacred. Types of trees such as the ash, oak, cocoa, and silk cotton were said to possess powers that would ensure the flourishing of animals, the land, and communities at large. In poetry and art trees were often personified and qualities such as wisdom, hope, and perseverance were bestowed upon them. The seasons of nature and life cycles were connected to tree life.

The tree of life is often used as a metaphor to describe evolution. References to the sacred cosmic tree can be traced back thousands of years from Babylonia (modern day Iraq) (3,000 – 4,000 BC). Many Indigenous cultures believe that there is a spirit in every tree, plant, rock, and animal. In The Illustrated Golden Bough, Frazer (1996) writes that “the Iroquois believed that each species of tree, shrub, plant, and herb had its own spirit, and to these spirits it was their custom to return thanks “ (Frazer, 1996, p. 92). The souls of the dead were thought to animate trees in mysterious ways. “If Theories of animism and transmigration upheld in Buddhist teachings propose that trees hold the souls and that to destroy branches wantonly would be akin to dispossessing a soul. Learners can explore the mythology surrounding trees and compare the way ancient cultures elevated trees to a sacred status with the crisis of deforestation that had led to the destruction of rain forests worldwide. How can the “reverence for nature” be renewed?

The cosmic tree is a universal archetype that resurfaces in world myths, literature, philosophy, and art. The tree is often viewed as a a metaphor for life and evolution. The Norse cosmos and the nine worlds are linked to the Ash tree, the Islamic tree of immortality, the Vedic “Kalpavriksha tree of life,” and the tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden reflect interconnecting dimensions of the human journey and life experiences. The figure of the serpent often associated with the cosmic tree can be symbolic not only of a force of evil that threatens the tree’s survival but the serpent might also be symbolic of a shamanic transcendent experience where a transition from earthly to heavenly or spiritual existence can occur. In The Red Book (Liber Novus) The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung embarked on a journey of self-study where he recorded his visions, reflections, and dreams. He recorded his thoughts between 1915-1930. Along with other symbols and archetypes, Jung identified the tree as a recurring archetype whose roots in the ground toward the shadow realms where the source of water and life are, its branches also sought nourishment from above and from the celestial roof of life. In life, one journeys through sadness and despair to self-knowledge and a deeper spiritual understanding of life. Trees were also mysterious and reflected many enigmas in life, according to Jung. Jung wrote that “through its branches and leaves the tree gathers the powers of light and air, and through its roots those of the earth and the water. ~Carl Jung Letters Vol. II, pp. 163-174.

Retrieved August 27, 2022. https://carljungdepthpsychologysite.blog/2020/08/11/carl-jung-on-trees-anthology/#.YwprgtPMI2w

Jaffe, A. & H.F. C Hull (trans.). (2015). Letters of Carl G. Jung 1956-Volume 1), Routledge.

Thomas Cole, The Titan’s Goblet, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, US.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10499

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Titan%27s_Goblet_MET_DP-12799-001.jpg

Courtesy: Gift of Samuel P. Avery Jr., 1904. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10499” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes on Thomas Cole’s Titan’s Goblet:

“Significant parallels between the Cosmic Nordic Tree of Life and Thomas Cole’s Titan’s Goblet can be made. The goblet created by Thomas Cole can be described as a microcosm of the human world amid nature. Oceans, dense forests, mountains, and other features of nature spread out from the goblet of life. The stem of the goblet can be compared to the trunk of the Nordic Cosmic tree whose roots and branches reach out to different parts of the cosmic. Thomas Cole’s work is set to be a culmination of Cole’s romantic fantasies and his idyllic view of nature and the cosmos. Cole believed that the artist and poet had special intermediary roles that could help individuals see and understand the connection between the past and the present and between nature and the divine. The Titan’s Goblet might also symbolize the grandeur of the past, the passage of time, and the encompassing power of nature.” (Retrieved July 15, 2023 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10499)

For more details, please open the link below from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10499

Courtesy: By Gustav Klimt – thewholegardenwillbow.wordpress.com, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12391960

Asgard: Home of the Gods

Artists envisioned Asgard in idyllic ways. The Rainbow joined different regions of the cosmic realm.

Courtesy: By Hermann Burghart – http://www.kulturundwein.com/juedisches-museum.htm 2014-02-23 12:14:34, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31302777

Courtesy: Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase Gallery Fund). “https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.166428.html” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

The Cosmic Tree — The Botanical Mind

https://www.botanicalmind.online/chapter-cosmic-tree

https://historylists.org/other/list-of-norse-gods-and-goddesses.html

Art Inspired by the Norse Sagas and Folktales

Courtesy: Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, The Fine Art Collections. Høstland, Børre. “https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/en/collection/object/NG.M.03666” is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Courtesy: By Johannes Gehrts – http://www.lippische-wochenschau.de[dead link], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6381855

Courtesy: By James Doyle Penrose – https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/idun-and-the-apples-2378756, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78075102

https://ia904704.us.archive.org/14/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.281979/2015.281979.Teutonic-Myth.pdf

Note about the author

Donald Alexander Mackenzie (24 July 1873 – 2 March 1936) was a Scottish folklorist and a prolific writer on mythology anthropology in the early 20th century (Wikimedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Alexander_Mackenzie).

Teutonic Myths and Legends by Donald A. MacKenizie. Gresham Publishing. Covent Garden, London, 1912.

https://ia904704.us.archive.org/14/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.281979/2015.281979.Teutonic-Myth.pdf

The Gutenberg eBook of Indian Myth and Legend, by Donald A. Mackenzie

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Idun_and_the_Apples.jpg

http://www.timelessmyths.com/norse/thor.html (direct link: http://www.timelessmyths.com/norse/gallery/idun2.jpg)

Wikimedia Note

“Ostara” (1901) by Johannes Gehrts. The goddess Ēostre/*Ostara flies through the heavens surrounded by Roman-inspired putti, beams of light, and animals. Germanic peoples look up at the goddess from the realm below.”

Courtesy: By Eduard Ade – Felix Dahn, Therese Dahn, Therese (von Droste-Hülshoff) Dahn, Frau, Therese von Droste-Hülshoff Dahn (1901). Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Für Alt und Jung am deutschen Herd. Breitkopf und Härtel., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4643479

For more stories please open the link below:

Books about Norse Mythology, Folklore, and Tales (Selections)

Project Gutenberg:

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/subject/4932

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ostara_by_Johannes_Gehrts.jpg

Otto Schenk (1930_)

Asgard and Valhalla

This is a visual interpretation of Richard Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold as directed by Otto Schenk.

- Retrieved August 24, 2022. Wikimedia This is a picture of visual interpretation of the Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold as directed by Otto Schenk.

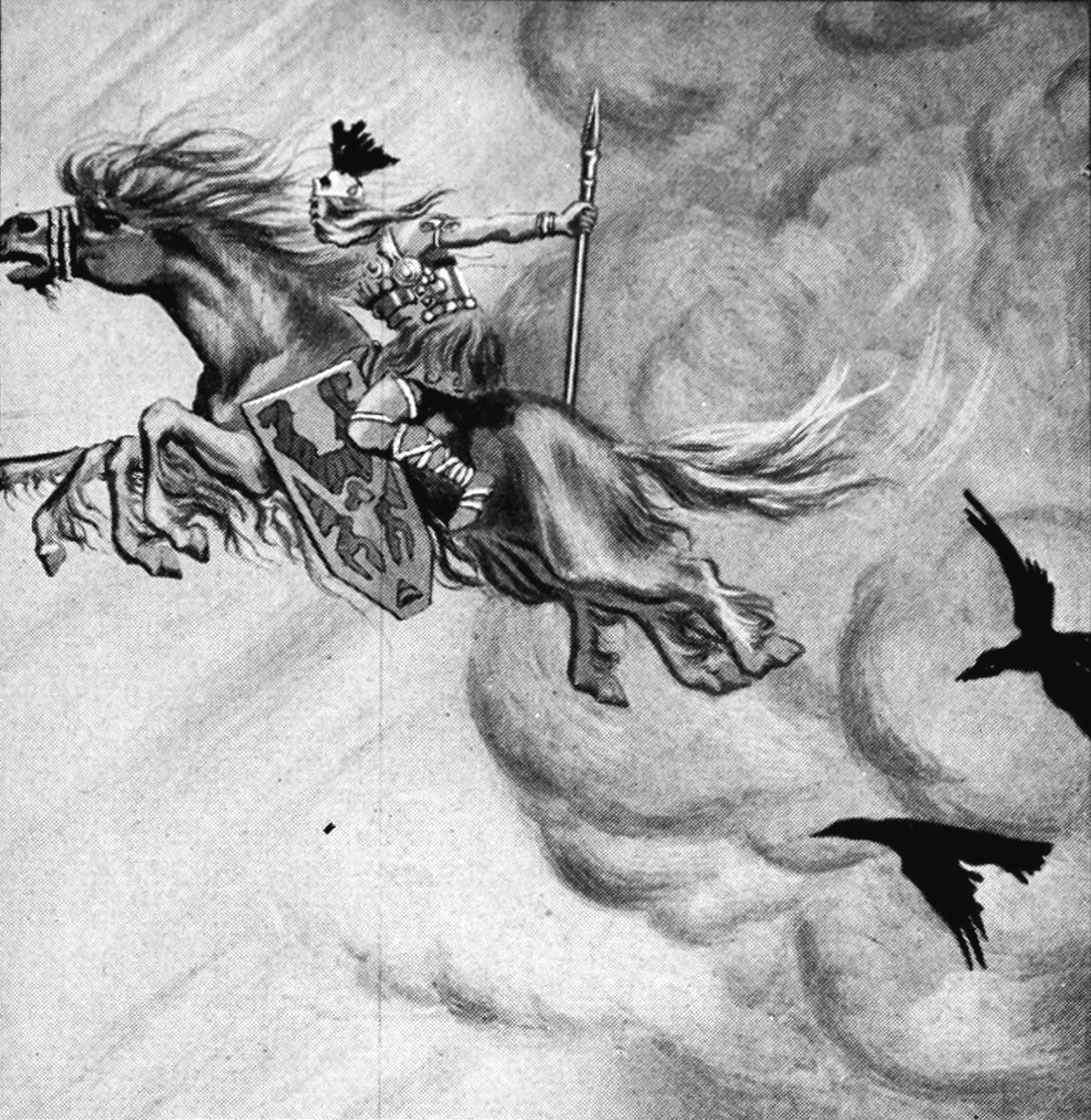

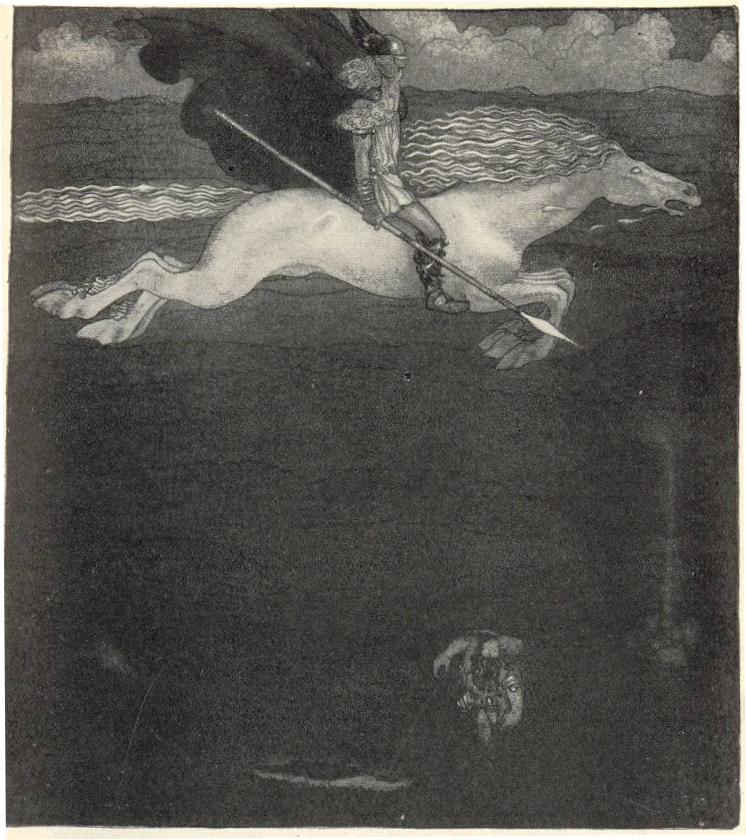

Slepinir, the Eight -Legged Horse

Horses in Scandanavian legend and folklore were thought to possess supernatural abilities. They were intermediaries between the earthly and spiritual/heavenly realms.

For more detail please open the link below.

Sleipnir & Woton in pursuit of Bruinhild By Internet Archive Book Images https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14577557867/Source book page: https://archive.org/stream/victrolabookofop00vict/victrolabookofop00vict#page/n542/mode/1up, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43416512

Norse Story of Creation from The Prose Edda and the Viking Sagas

“The myth is the oldest form of truth; and mythology is the knowledge which the ancients had of the Divine. The object of mythology is to find God and come to him. Without a written revelation this may be done in two ways: either by studying the intellectual, moral and physical nature of man, for evidence of the existence of God may be found in the proper study of man; or by studying nature in the outward world in its general structure, adaptations and dependencies; and truthfully it may be said that God manifests himself in nature.” (R.B. Anderson)

Courtesy: By Nicolai Abildgaard – mechanical reproduction of 2D image, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=639093

Viking Worlds

In their book The Vikings, Chartrand, Durham, Harrison, and Heath (2019) explain that like many cultures, the Vikings saw a distinct interconnection between human life and the intricacies of nature:

““The Vikings usually worshipped their gods in the open air-at ancient sites, sacred groves, or on islands—although occasionally people congregated in wooden temples, which contained carved images of the various deities.

The Norsemen viewed their world as a flat disc surrounded by a vast ocean and here, coiled around the earth, dwelt the Midgard Serpent (daughter of the trickster Loki). Supporting the earth was the giant ash tree, Yggdrasill, whose roots stretched from the freezing depths of Hel to Jotunheim, the home of the giants,which lay on the far side of the ocean at the world’s end. Beneath the roots of Yggsdrasilll lay the Well of Fate and Wisdom, which was tended by the Norns, three spirits who wove the threads of destiny. Chained to a rock at the centre of the earth was the ravenous wold Fenrir, whose jaws stretched across the universe. Mankind dwelt in a realm known as Midgard and lived under the protection of many deities, the most important of which were the Aesir who lived in Asgard, the stronghold of the gods ” (p. 39).

Source: Chartrand, R., Durham, K., Harrison, M, and Heath, I. (2019) The Vikings. Osprey Publishing.

Courtesy: By Lorenz Frølich, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=399486

The Rainbow Bridge

Otto Schenk (1930- )The Rainbow Bridge. Courtesy: Art Libre License.

Wikimedia Commons. Asgard and Bifrost in the interpretation of Otto

Schenk (1930-) in Wagner’s Das Rheingold.jpg

Nationalmuseum Sweden artwork ID: 18255 Edit this at Wikidata

Courtesy: By Max Brückner – https://web.archive.org/web/20150123030733/http://www.nordische-mythologie.de/html/gallery/pages/s213-4.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4754069

Courtesy: By Arthur Rackham – ; Rackham, Arthur (illus) (1910) The Rhinegold & the Valkyrie, London: William Heinemann, p. p. Retrieved on 23 June 2011., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15619268

Additional Links:

Maastricht Library Collection (https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q15734302).

Courtesy: Cecilia Heisser / Nationalmuseum. “https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=19222&viewType=detailView” is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

NORSE MYTHS

Courtesy: By Oscar Wergeland – Guerber, H. A. (Hélène Adeline) (1909). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. London : Harrap. This illustration is the frontispiece. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/mythsofthenorsem00gueruoft Some simple image processing by User:Haukurth., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4820110

A Land of Fire and Ice: Survival and Transcendence

To the people of the north, danger was always imminent in a harsh landscape with brutal winters and short summers. Similar to many Indigenous myths of creation, Nordic people viewed the earth as alive and had a life of its own; all living creatures were interconnected in some way. It is important to note the way landscape and geography influence individuals’ ways of thinking about the universe. In H.A. Guerber’s classic 1909 Myths of the Norsemen, we read that:

“The grand and rugged landscape of Northern Europe, the midnight sun, the flashing rays of the aurora borealis, the ocean continually lashing itself into fury against the great cliffs and icebergs of the Artic Circle could not but impress the people as vividly as the almost miraculous vegetation, the perpetual light, and the blue seas and skies of their brief summer seasons. It is no great wonder, that the Icelanders, for instance to whom we owe the most perfect records of this belief, fancied in looking about them that the world was originally created from a strange mixture of fire and ice.” (Guerber, 1909, Project Gutenberg, 2006, p. 9).

Similarities between Indigenous and Inuit myths of creation and the stories of the Norsmen can be found. For example, Odin (All-Father) is also referred to as the Raven god who is all-knowing. The ravens are spiritual messengers and they are revered for the wisdom and intelligence in both cultures. The dominance force of nature and the elements play a factor in these cultures. The myths and legends attempted to explain suffering, hardship, atonement, and joy.

Yggdrasil or the tree of the universe was central to the Nordic creation myths. The giant mystical ash tree was guarded and tended to by three norns (the goddesses of fate); the tree was ever green and never withering.

Jesse Byock (2005) writes, that “the concept of the world tree is thousands of years old and that it may have an Indo-European origin The cosmic pillar at the centre is descried as a giant ash tree that bound together different parts of the universe; the tree was a symbol of the dynamic cosmic always in a state of change. Below the tree’s branches like the home of the gods (Asgard) and the norns or the goddesses of fate. “From Asgard the Rainbow Bridge, Bifrost, leads down to Midgard (Middle Earth) and the home of men.” The underworld which contained serpents and other monster was considered to be in the realm of the dead. Symbolic of the powers of destruction and a portend of the “twilight of the gods” or Ragnarok, a dragon called Nidhug continually gnawed at its roots, hoping to kill the tree. Like humans, the ash tree endures hardship and while “stag bites from above and its sides rot; From below Nidhogg gnaws” (The Lay of Grimnir, p. 44).

Friedrich Wilhelm Hein

Yggdrassil

In this poem from “The Lay of Grimnir”, the ash tree is compared to other supreme beings of power, including Odin, the head of all gods (Aesirs) and the most powerful and magical eight legged horse Sleipnir (p. 44 (In Byock, 2005, Ed., p. 50).

“The ash Yggdrasil

Is foremost of trees,

And Skidbladnir of ships,

Odin of the Aesir,

And of the stallion, Sleipnir,

Bifrost of the bridges,

And Bragi of skalds,

Habrok of hawks,

and of hounds, Garm.” (In Byock, 2005, p. 50)

The Well of Mimir

Courtesy: By Robert Engels (1866-1920). – Lange, Adolf (1903). Deutsche Götter- und Heldensagen. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig. Page 44. Digitized version from Google Books., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5134946

Charles Sylvester, Journeys through Bookland (Digitized in 2009).

https://archive.org/details/journeysthroughb01sylv/page/n7/mode/1up?view=theater

Nine Realms of Norse Mythology

https://vikingr.org/norse-cosmology/nine-realms-of-norse-mythology

Yggdrasil by Finnur Magnússon (Illustration) – World History Encyclopedia

https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13625/yggdrasil-by-finnur-magnusson/

The Illustrated Map of the Nine Worlds:

https://vikingr.org/norse-cosmology/norse-ragnarok

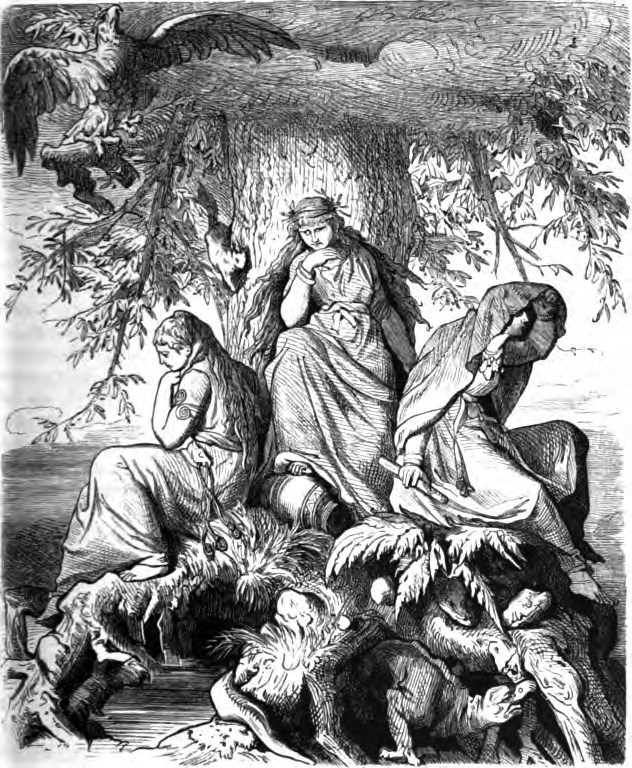

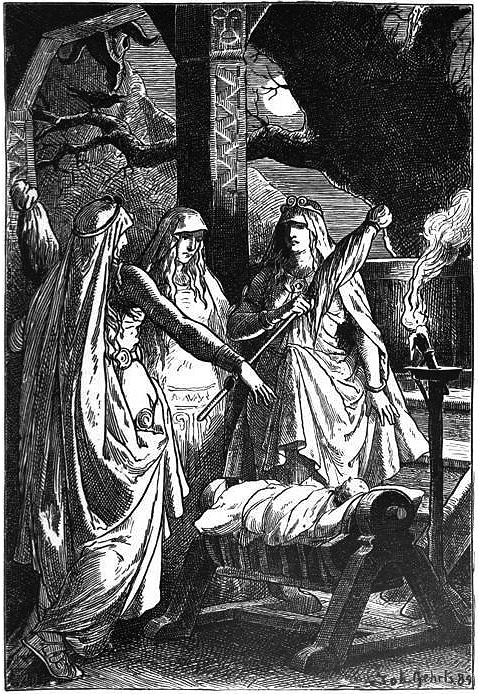

Three Norns or Fates Guarding the Cosmic Tree Yggdrassil

In The Prose Edda, Snori Sturluson describes the importance of the sacred ash. Nine different realms of the ash tree interconnect with one another.

Controlling the Fate of Humans: The Three Norns under Yggdrasil

The Nornic trio of Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld beneath the world tree (Yggdrasil-ash tree). At the top of this tree is an eagle (likely Veðrfölnir), on the trunk of the tree is a squirrel (likely Ratatoskr), and at the roots of the tree gnaws what appears to be a small dragon (likely Níðhöggr). At the bottom left of the image is the well Urðarbrunnr.

Courtesy: By Ludwig Burger (1825-1884). – Wägner, Wilhelm. 1882. Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden. Otto Spamer, Leipzig & Berlin. Page 231., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5240093

“Captioned as “Die Nornen Urd, Werdanda, Skuld, unter der Welteiche Yggdrasil”. The Nornic trio of Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld beneath the world tree (called an oak in the caption) Yggdrasil. At the top of the tree is an eagle (likely Veðrfölnir), on the trunk of the tree is a squirrel (likely Ratatoskr), and at the roots of the tree gnaws what appears to be a small dragon (likely Níðhöggr). At the bottom left of the image is the well Urðarbrunnr.” (Retrieved July 20, 2023 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ludwig_Burger#/media/File:Die_Nornen_Urd,_Werdanda,_Skuld,_unter_der_Welteiche_Yggdrasil_by_Ludwig_Burger.jpg).

The Three Norns that shape the fate of individuals are: Urd (Fate); Verdandi (Becoming), and Skuld (Obligation). Depending on whether the norns are good or bad, an individual’s fate turns out quite differently. “If the norns decide the fates of [men], then they do so in a terribly uneven manner. Some people enjoy a good and prosperous life, whereas others have little wealth or renown. Some have a long life, but others, a short one.”(Sturleson in Byock, 2005, p. 26).

Courtesy: By Johan Ludwig Lund – Originaly from en:Image:Nornir by Lund.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=635370

Courtesy: By Johannes Gehrts – Felix Dahn, Therese Dahn, Therese (von Droste-Hülshoff) Dahn, Frau, Therese von Droste-Hülshoff Dahn (1901).Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Für Alt und Jung am deutschen Herd. Breitkopf und Härtel., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4624295

http://www.germanicmythology.com/PoeticEdda/GRM31HEL.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Viking_art

Verdande under Ash Tree_Cosmic Ash Tree Sacred Ash Tree

https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/yggdrasil-the-sacred-ash-tree-of-norse-mythology

Project Gutenberg_Prose Edda with Illustrations

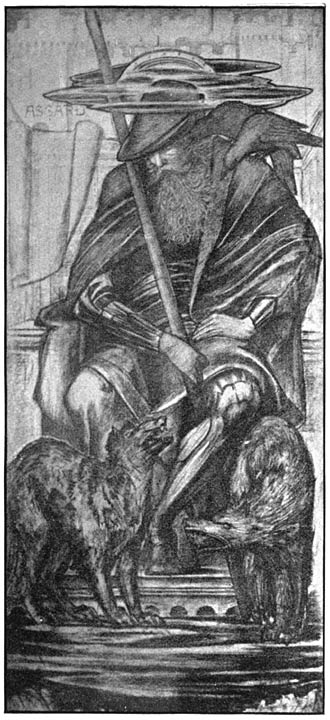

Odin (Wotan), the King of Gods (All-Father)

Courtesy: Guerber, H. A.. (April 4, 2009). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. Project Gutenberg (Public Domain). Retrieved August 16, 2023, from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm#p016

Sir Edward Burnes Coley Jones, one of the great Pre-Raphaelite painters depicts Odin with the two ravens (Huin and Munir) and his two wolves (Jerri and Frekki). Geri and Freki were considered sacred to Odin and were a good omen. When Odin wandered the earth in human guise, as Guerber (1909) writes, “he wore a broad-brimmed hat drawn low over his forehead to conceal the fact that he possessed but one eye” (p. 20).

Odin

“Odin rules in all matters, and although the other gods are powerful, all serve him as children do their father. Frigg is his wife. She knows the fates of men, even though she pronounces no porphecies. Odin is called All-Father, because he is the father of all the gods. He is also called Father of the Slain (Val-Father) because all gods who fall in battle are his adopted sons. With them he mans Valhalla and VIngolf, and they are known as the Einherjar. He is also called Hanga-God (God of the Hanged), Hapta-God (God of Prisoners), and Farma -God (God of Cargoes), and he is named himself in many other ways….( Prose Edda in Byock, 2005, pp.30-31).”

“Two ravens sit on Odin’s shoulders, and into his ears they tell all the news they see or hear. Their names are Hugin (Thought) and Munin (Mind, Memory). At sunrise, he sends them off to fly throughout the whole world, and they return in time for the first meal. Thus he gathers knowledge about many things that are happening, and so people call him the raven god.” (Prose Edda, in Byock, p.47).

From H.A. Guerber: Myths of the Norseman The Eddas and Sagga, 1909. George G. Harrap & Co. , Covent Garden, UK.

Detail about Odin’s Personal Appearance

‘None but Odin and his wife and queen Frigga were privileged to use this seat, and when they occupied it they generally gazed towards the south and west, the goal of all the hopes and excursions of the Northern nations. Odin was generally represented as a tall, vigorous man, about fifty years of age, either with dark curling hair or with a long grey beard and bald head. He was clad in a suit of grey, with a blue hood, and his muscular body was enveloped in a wide blue mantle flecked with grey—an emblem of the sky with its fleecy clouds. In his hand Odin generally carried the infallible spear Gungnir, which was so sacred that an oath sworn upon its point could never be broken, and on his finger or arm he wore the marvellous ring, Draupnir, the emblem of fruitfulness, precious beyond compare. When seated upon his throne or armed for the fray, to mingle in which he would often descend to earth, Odin wore his eagle helmet; but when he wandered peacefully about the earth in human guise, to see what men were doing, he generally donned a broad-brimmed hat, drawn low over his forehead to conceal the fact that he possessed but one eye. ” (Guerber, 1909, p. 20).

“Two ravens, Hugin (thought) and Munin (memory), perched upon his shoulders as he sat upon his throne, and these he sent out into the wide world every morning, anxiously watching for their return at nightfall, when they whispered into his ears news of all they had seen and heard. Thus he was kept well informed about everything that was happening on earth.” (Guerber, 1909, p.20-21)

“Hugin and Munin

Fly each day

Over the spacious earth.

I fear for Hugin

That he come not back,

Yet more anxious am I for Munin.”

(In Helene A., Guerber (1909) Myths of the Norsemen: The Eddas and Saggas.

Project Gutenberg eBook. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm

Courtesy: By Carl Emil Doepler (1824-1905) – Wägner, Wilhelm. 1882. Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden. Otto Spamer, Leipzig & Berlin. Page 7., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5251205

Courtesy: By John Bauer – for Our Fathers’ Godsaga by Viktor Rydberg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=833923

Special Attributes of the Gods (Byock, 2005)

“The gods have special attributes, but many pay for their powers with related loss. Odin, the god who sees all, loses an eye; Tyr, a god of war and council, breaks his pledge and loses his hand crucial for making oaths and wielding weapons); Freya, the goodess of household prosperity, leave her hearth to search for her husband who has wandered off. Unlike the gods of Greek and Roman mythology, the AEsir rarely quarrel among themselves over control of human or semi-divine heroes, nor do they enjoy the complacency of immortality. Their universe is constantly in danger, and their actions frequently have unanticipated consequences, as in the creation story, when Odin and his brother slay the giant Ymir and use his body to fill Ginnungagap, the primeval void. While this act gives rise to the world of the Eddas, the slaying also unleashes the power of the giants, the gods’ enemies.” (Byock, 2005, pp. xvii-xviii).

Courtesy: By The book gives the artist alternatively as Dielitz, K. Presumably this is Konrad Dielitz (1845 – 1933). – Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham. 1892. Character sketches of romance, fiction and the drama. A revised American edition of the Readers’ handbook. Volume IV. Facing page 52. Digitized version from University of Wisconsin Digital Collections: [1]. Additional information: [2]., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5158958

Courtesy: By Emil Doepler – Doepler, Emil. ca. 1905. Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Top portion of page 12. Photographed by Haukurth (talk · contribs) and cropped by Bloodofox (talk · contribs)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5220642

Courtesy: By John Charles Dollman – Guerber, H. A. (Hélène Adeline) (1909). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. London : Harrap. This illustration facing page 42. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/mythsofthenorsem00gueruoft Some simple image processing by User:Haukurth. Previous upload from http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/mss/online/online-exhibitions/exhib_ice/b5.phtml, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=677061

Frigg: Queen of the Gods

Frigg (“Beloved”) was the queen of the gods. She is the most powerful of the Aesir goddesses. Frigg is the wife of Odin, the leader of the gods, and Baldr’s mother. H.A. Guerber (1909) writes:

“Frigga or Frigg was goddess of the atmosphere, or rather of the clouds, and as such was represented as wearing either snow-white or dark garments, according to her somewhat variable moods. She was queen of the gods, and she alone had the privilege of sitting on the throne Hlidskialf, beside her august husband (Odin). From thence she too could look over all the world and see what was happening, and according to the belief of our ancestors, she possessed the knowledge of the future, which, however, no one could ever prevail upon her to reveal, thus proving that Northern women could keep a secret inviolate.

Frigga was generally represented as a tall, beautiful, and stately woman, crowned with heron plumes, the symbol of silence or forgetfulness, and clothed in pure white robes, secured at the waist by a golden girdle, from which hung a bunch of keys….Although she often appeared beside her husband, Frigga preferred to remain in her own palace called Fensalir, the hall of mists or of the sea, where she diligently plied her wheel or distaff, spinning golden thread or weaving long webs of bright-coloured clouds” (Guerber, 1909, in Project Gutenberg, p. 38, The Myths of the Norsmen).

H.C. Henneberg and C. Hanson. Odin.

Illustration from the Historical Fables and Myths of Denmark, p. 112.

The Valkyries

Courtesy: Viktor Fordell / Nationalmuseum. “https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=18255&viewType=detailView” is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Courtesy: By John Charles Dollman – Guerber, H. A. (Hélène Adeline) (1909). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. London : Harrap. This illustration facing page 176. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/mythsofthenorsem00gueruoft Some simple image processing by User:Haukurth., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4785164

Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas (gutenberg.org)

John Charles Dollman Illustrations (germanicmythology.com)

Courtesy: By Ferdinand Leeke – Dorotheum: Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113379038

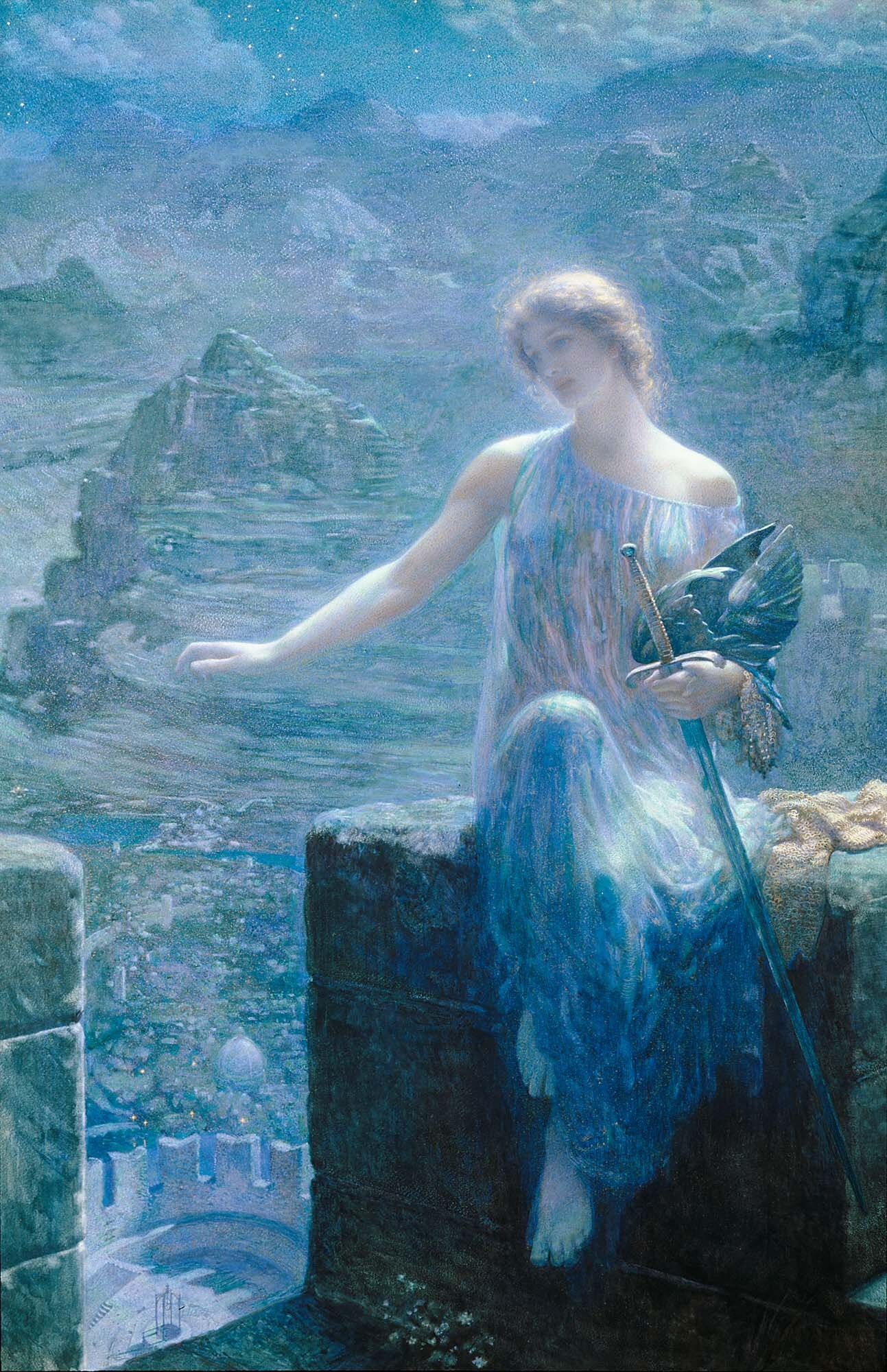

The Valkyrie’s Vigil

Courtesy: By Edward Robert Hughes – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=212360

“Hughes interprets Richard Wagner’s epic operatic drama depiction of a Valkyrie in a type of fairy painting. The valkyrie’s warrior aspects de-emphasized. Her helmet is in her hand, she is in a contemplative pose, and her horse, wolf, and raven are not present” (Retrieved July 20, 2023 Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Valkyrie’s_Vigil.jpg#/media/File:The_Valkyrie’s_Vigil.jpg).

Courtesy: By Arthur Rackham – ; Rackham, Arthur (illus) (1910) The Rhinegold & the Valkyrie, London: William Heinemann, p. p. Retrieved on 23 June 2011., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15618974

For the complete book The Valkyrie and the Rhinegold (1910) with Illustrations by Arthur Rackham, please open the link below.

Project Gutenberg eBook :

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/48214/48214-h/48214-h.htm

Courtesy: By Arthur Rackham – ; Rackham, Arthur (illus) (1910) The Rhinegold & the Valkyrie, London: William Heinemann, p. p. 22 Retrieved on 23 June 2011., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15619057

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/48214/48214-h/48214-h.htm

Courtesy: By Eduard Ade – Felix Dahn, Therese Dahn, Therese (von Droste-Hülshoff) Dahn, Frau, Therese von Droste-Hülshoff Dahn (1901). Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Für Alt und Jung am deutschen Herd. Breitkopf und Härtel., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curie=4642785

Freya

Freya was the Nordic goddess of love and compassion. She sets about on her sleigh with her cats Honey and Amber looking the heavens and earth for her husband. R. B. Anderson writes:

Freya: Goddess of Love and Harmony

“The goddess of love is Freyja, also called Vanadis or Vanabride. She is the daughter of Njord and the sister of Frey. She ranks next to Frigg. She is very fond of love ditties, and all lovers would do well to invoke her. It is from her name that women of birth and fortune are called in the Icelandic language hús freyjur (compare Norse fru and German frau). Her abode in heaven is called Folkvang, where she disposes of the hall-seats. To whatever field of battle she rides she asserts her right to one half the slain, the other half belonging to Odin. Thus the Elder Edda, in Grimner’s lay:

Her mansion, Sessrymner (having many or large seats), is large and magnificent; thence she rides out in a car drawn by two cats. She lends a favorable ear to those who sue for her assistance. She possesses a necklace called Brisingamen, or Brising. She married a person called Oder, and their daughter, named Hnos, is so very handsome that whatever is beautiful and precious is called by her name hnossir (that means, nice things). It is also said that she had two daughters, Hnos and Gerseme, the latter name meaning precious. But Oder left his wife in order to travel into very remote countries. Since that time Freyja continually weeps, and her tears are drops of pure gold; hence she is also called the fair-weeping goddess (it grátfagra goð). In poetry, gold is called Freyja’s tears, the rain of Freyja’s brows or cheeks. She has a great variety of names, for, having gone over many countries in search of her husband, each people gave her a different name. She is thus called Mardal, Horn, Gefn, Syr, Skjalf and Thrung.” (R.B. Anderson).

RASMUS B. ANDERSON, LL.D.,

Courtesy: By Jacques Reich – Bradish, Sarah Powers. (1900) Old Norse Stories, page 19. American Book Company, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4175244

Excerpt from H.A. Guerber (1909) The Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas. George G. Harrap & Co.

“Frey, the god of the golden sunshine and the warm summer showers, took up his abode, charmed with the society of the elves and fairies, who implicitly obeyed his every order, and at a sign from him flitted to and fro, doing all the good in their power, for they were pre-eminently beneficent spirits.

Frey also received from the gods a marvellous sword (an emblem of the sunbeams), which had the power of fighting successfully, and of its own accord, as soon as it was drawn from its sheath. Frey wielded this principally against the frost giants, whom he hated almost as much as did Thor, and because he carried this glittering weapon, he has sometimes been confounded with the sword-god Tyr or Saxnot.”

“With a short-shafted hammer fights conquering Thor;

Frey’s own sword but an ell long is made.”

Viking Tales of the North (R. B. Anderson).

“The dwarfs from Svart-alfa-heim gave Frey the golden-bristled boar Gullin-bursti (the golden-bristled), a personification of the sun. The radiant bristles of this animal were considered symbolical either of the solar rays, of the golden grain, which at his bidding waved over the harvest fields of Midgard, or of agriculture; for the boar (by tearing up the ground with his sharp tusk) was supposed to have first taught mankind how to plough.”

( R.B. Anderson, in H. Guerber, 1909, pp. 117-118).

For the complete stories of the Norsemen by Helen Guerber, please open the Project Gutenberg link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm

Courtesy: Cecilia Heisser / Nationalmuseum. “https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=18201&viewType=detailView” is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Courtesy: By Ludwig Pietsch (1824-1911) – Murray, Alexander (1874). Manual of Mythology : Greek and Roman, Norse, and Old German, Hindoo and Egyptian Mythology. London, Asher and Co. This illustration is from plate XXXVII. Digitized version of the book by the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/manualofmytholog00murruoft Published earlier in Reusch, Rudolf Friedrich. 1865. Die nordischen Göttersagen., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4777144

Freya and Frey

“The sea god Njord of Noatum had two children (mother was unknown). “The son was called Frey and the daughter Freyja. They were beautiful and powerful. Frey is the most splendid of gods. He controls the rain and the shining of the sun, and through them the bounty of the earth. I tis good to invoke him for peace and abundance. He also determines men’s success in prosperity. Freyja is the most splendid of the goddesses. She has a home in heaven called Fokvangar (Warrior’s Fields). Where ever she rides into battle, half of the slain belong to her. Odin takes the other have…When she travels, she drives a chariot drawn by two cats. She is easily approachable for people who want to pray to her and from her name comes the title of honour whereby women of rank are called frovur for ladies. She delights in love songs, and it s good to call on her in matters of love” (Byock, 2005, Sturleson Prose Edda, p. 35).”

Snorri Sturleson, The Prose Edda translation by J. Byock, Penguin Books, 2005.

Freya and Heimdall (enigmatic Norse god of phrophecy and perception):

Courtesy: By Nils Blommér – Sv:, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55297

For more resources on the myths behind the art please open the links below.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Norse mythology; or The religion of our forefathers, containing all the myths of the Eddas, systematized and interpreted, by Rasmus Björn Anderson https://www.gutenberg.org/files/65910/65910-h/65910-h.htm

“Smycket Bryfing” (actually Brisingasmycket) means Brísingamen. According to Skáldskaparmál (and Húsdrápa), Heimdall and Loki fought over it and Heimdall got the upper hand.

Courtesy: By James Doyle Penrose (1862-1932) – https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/freyja-and-the-necklace-2378757, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78074104

Courtesy: By Johannes Gehrts – Felix Dahn, Therese Dahn, Therese (von Droste-Hülshoff) Dahn, Frau, Therese von Droste-Hülshoff Dahn (1901). Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Für Alt und Jung am deutschen Herd. Breitkopf und Härtel., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4643348

Baldur or Baldr:

In this 1901 illustration by Johannes Gehrts, Baldr is hold plants and a sun-shaped shield. Baldr is described as Odin’s second son and “there is much good to tell about him. He is the best, and all praise him. He is so beautiful and so bright that light shines from him. One plant is so white that it is liked to Baldr’s brow. It is the whitest of all plants, and from this you can judge the beauty of both his hair and his body. He is the wisest of the gods. He is also the most beautifullly spoken and the most merciful, but one of his characteristics is that none of his decisions is effective. He lives at a place called Breidadblik. It is in heaven, and no impurity may be there..” (Sturleson, Prose Edda, in Byock, Ed. 2005, p. 33).

Loki, the trickster god, is jealous of Baldr and orchestrates his death. The one thing lethal to Baldr was mistletoe and his is hit by an arrow of misteltoe and dies.

Courtesy: By Emil Doepler – Doepler, Emil. ca. 1905. Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Page 14. Photographed and cropped by Haukurth (talk · contribs)., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5213233

Loki: The Trickster God

Loki was known as the Trickster god in Nordic Mythology. He is also known as “the source of deceit” (Byock, 2005). His beauty and ability to be a shape shifter that could take on any form enabled him to manipulate and controle others. Loki was said to be the son of the giant Farbaut. “Loki is pleasing, even beautiful to look at, but his nature is evil and he is undependable. More than others, he has the kind of wisdom known as cunning and is treacherous in all matters. He constantly places the gods in difficulties and often solves their problems with guile “(Byock, 2005 Trans. of Snorri Sturleson’s The Prose Edda, Penguin Books, pp. 38-39).

For the complete tales of The Children of Odin by Colum Padraic (and illustrated by the artist Willy Pogany) please open the Project Gutenberg eBook link below.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/24737/24737-h/24737-h.htm

Loki The Betrayer from Colum Padric’s (1920) The Children of Odin.

“He stole Frigga’s dress of falcon feathers. Then as a falcon he flew out of Asgard. Jötunheim was the place that he flew toward. The anger and the fierceness of the hawk was within Loki as he flew through the Giants’ Realm. The heights and the chasms of that dread land made his spirits mount up like fire. He saw the whirlpools and the smoking mountains and had joy of these sights. Higher and higher he soared until, looking toward the South, he saw the flaming land of Muspelheim. Higher and higher still he soared. With his falcon’s eyes he saw the gleam of Surtur’s flaming sword. All the fire of Muspelheim and all the gloom of Jötunheim would one day be brought against[Pg 156] Asgard and against Midgard. But Loki was no longer dismayed to think of the ruin of Asgard’s beauty and the ruin of Midgard’s promise.” (Padric, 1920, p. 156).

To read the complete tale of Loki, please open the Project Gutenberg eBook below:

Courtesy: By Emil Doepler – Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Page 43., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5225478

Courtesy: By W.G. Collingwood (1854 – 1932) – The Elder or Poetic Edda; commonly known as Sæmund’s Edda. Edited and translated with introduction and notes by Olive Bray. Illustrated by W.G. Collingwood (1908) Page 39. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/elderorpoeticedd01brayuoft This image was made from the JPEG 2000 image of the relevant page via image processing (crop, rotate, color-levels, mode) with the GIMP by User:Haukurth. The image processing is probably not eligible for copyright but in case it is User:Haukurth releases his modified version into the public domain., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4657760

The Death of Baldur (Baldr):

“The beginning of this tale is, that Balder dreamed dreams great and dangerous to his life. When he told these dreams to the asas they took counsel together, and it was decided that they should seek peace for Balder against all kinds of harm. So Frigg exacted an oath from fire, water, iron and all kinds of metal, stones, earth, trees, sicknesses, beasts, birds and creeping things, that they should not hurt Balder. When this was done and made known, it became the pastime of Balder and the asas that he should stand up at their meetings while some of them should shoot at him, others should hew at him, while others should throw stones at him; but no matter what they did, no harm came to him, and this seemed to all a great honor. When Loke, Laufey’s son, saw this, it displeased him very much that Balder was not scathed. So he went to Frigg, in Fensal, having taken on himself the likeness of a woman. Frigg asked this woman whether she knew what the asas were doing at their meeting. She answered that all were shooting at Balder, but that he was not scathed thereby. Then said Frigg: Neither weapon nor tree can hurt Balder, I have taken an oath from them all. Then asked the woman: Have all things taken an oath to spare Balder? Frigg answered: West of Valhal there grows a little shrub that is called the mistletoe, that seemed to me too young to exact an oath from. Then the woman suddenly disappeared. Loke went and pulled up the mistletoe and proceeded to the meeting. Hoder stood far to one side in the ring of men, because he was blind.

Loke addressed himself to him, and asked: Why do you not shoot at Balder? He answered: Because I do not see where he is, and furthermore I have no weapons. Then said Loke: Do like the others and show honor to Balder; I will show you where he stands; shoot at him with this wand. Hoder took the mistletoe and shot at Balder under the guidance of Loke. The dart pierced him and he fell dead to the ground. This is the greatest misfortune that has ever happened to gods and men. When Balder had fallen, the asas were struck speechless with horror, and their hands failed them to lay hold of the corpse.”

Tales of the Edda by Snorri Sturleson translated by Rasmus B. Anderson. Project Gutenberg ebook.

The most handsome and gentle of the gods, Baldr is killed by the mistletoe, the one fatal plant. Loki the

Odin whispers last words to his son Baldr.

Death of Baldr.

Courtesy: By Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg – Self-scanned, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=677059

http://norse-mythology.org/tales/the-death-of-baldur/

“Baldr is lying in the foreground. He has just been hit by Höd’s missile. Höd, Baldr’s blind brother, is standing on the left, stretching his arms out. On the very left, Loki tries to conceal his smile. Odin is sitting in the middle of the Æsir. Thor is on his left. Yggdrasil and the three Norns can be seen in the background.” (Retrieved July 21, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baldr_dead_by_Eckersberg.jpg#/media/File:Baldr_dead_by_Eckersberg

Notes:

Thor, God of Thunder and the Skies

Courtesy: By Carl Emil Doepler (1824-1905) – Wägner, Wilhelm. 1882. Nordisch-germanische Götter und Helden. Otto Spamer, Leipzig & Berlin. Page 129., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5251239

Thor

Thor “is the strongest of all gods and men. He rules at the place called Thrudvangar (Plains of Strength) and his hall is called Bilskirnir….Thor hahs two male goats called Tanngniost (Tooth Gnasher) and Tanngrisnir (Snarl Tooth). He also own the charot that they draw, and for this reason he is a called Thor the Chariotter. He, too, has three choice possessions. One is the hammer Mjollnir. Frost giants and mountain giants recognie it when it is raised in the air, which is not suprizsing as it has cracked many a skull amog their fathers and kinsmen. His second great treasure is his Megingjard (Belt of Strenght). When he buckles it on, his divine strength doubles. His third possession, the gloves of iron, are also a great treasure. He cannot be without these when he grips the hammer’s shaft. No one is so wise that he can recount all of Thor’s important deeds….” (Byock, 2005, Trans. Snorri Sturluson Prose Edda, Penguin, p. 33).

Courtesy: Nationalmuseum of Sweden, Stockholm, Sweden, EU. LINK NEEDED.

Wikimedia Commons

Resources:

Alexander Murray, Norse Myths. https://books.google.ca/books?id=P4IBAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Courtesy: By Johannes Gehrts – Flickr, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1393337

Courtesy: Guerber, H. A.. (April 4, 2009). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. Project Gutenberg (Public Domain). Retrieved August 20, 2023, from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm#p018

“Besides the magnificent hall Glads-heim, where stood the twelve seats occupied by the gods when they met in council, and Valaskialf, where his throne, Hlidskialf, was placed, Odin had a third palace in Asgard, situated in the midst of the marvellous grove Glasir, whose shimmering leaves were of red gold” (Retrieved July 20, 2023, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm#p018).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28352852

Courtesy: By Mabel Dorothy Hardy – Guerber, H. A. (Hélène Adeline) (1909). Myths of the Norsemen from the Eddas and Sagas. London : Harrap. This illustration facing page 334. Digitized by the Internet Archive and available from https://archive.org/details/mythsofthenorsem00gueruoft Some simple image processing by User:Haukurth., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78946069

Ragnarok or The Twilight of the Gods:

When Gangleri (Glyfi, King of Sweden disguised as a traveller) ask the High One (Odin or Wotan) about the destruction of the world (Ragnarok) he answers that a severe and destructive winter will come. Odin/Har describes the apocalyptic setting:

“Then said Ganglere: What tidings are to be told of Ragnarok? Of this I have never heard before. Har answered: Great things are to be said thereof. First, there is a winter called the Fimbul-winter, when snow drives from all quarters, the frosts are so severe, the winds so keen and piercing, that there is no joy in the sun. There are three such winters in succession, without any intervening summer. But before these there are three other winters, during which great wars rage over all the world. Brothers slay each other for the sake of gain, and no one spares his father or mother in that manslaughter and adultery. Thus says the Vala’s Prophecy:

Brothers will fight together

And become each other’s bane;

Sisters’ children

Their sib shall spoil.

Hard is the world,

Sensual sins grow huge.

There are ax-ages, sword-ages—

Shields are cleft in twain,—

There are wind-ages, wolf-ages,

Ere the world falls dead.

Then happens what will seem a great miracle, that the wolf devours the sun, and this will seem a great loss. The other wolf will devour the moon, and this too will cause great mischief. The stars shall be Hurled from heaven. Then it shall come to pass that the earth and the mountains will shake so violently that trees will be torn up by the roots, the mountains will topple down, and all bonds and fetters will be broken and snapped. The Fenris-wolf gets loose. The sea rushes over the earth, for the Midgard-serpent writhes in giant rage and seeks to gain the land. The ship that is called Naglfar also becomes loose. It is made of the nails of dead men; wherefore it is worth warning that, when a man dies with unpared nails, he supplies a large amount of materials for the building of this ship, which both gods and men wish may be finished as late as possible. But in this flood Naglfar gets afloat. The giant Hrym is its steersman. The Fenris-wolf advances with wide open mouth; the upper jaw reaches to heaven and the lower jaw is on the earth. He would open it still wider had he room. Fire flashes from his eyes and nostrils. The Midgard-serpent vomits forth venom, defiling all the air and the sea; he is very terrible, and places himself by the side of the wolf. In the midst of this clash and din 142 the heavens are rent in twain, and the sons of Muspel come riding through the opening. Surt rides first, and before him and after him flames burning fire. He has a very good sword, which shines brighter than the sun. As they ride over Bifrost it breaks to pieces, as has before been stated. The sons of Muspel direct their course to the plain which is called Vigrid. Thither repair also the Fenris-wolf and the Midgard-serpent. To this place have also come Loke and Hrym, and with him all the frost-giants. In Loke’s company are all the friends of Hel. The sons of Muspel have there effulgent bands alone by themselves. The plain Vigrid is one hundred miles (rasts) on each side. ”

Storri Sturleson, ” Ragnarok”, Translated by Rasmus B. Anderson, LL.D. 1901. First Copyright, 1879 by S.C. Griggs & Company. Pres of The Henry O. Shepard Co., Chicago.

.tps://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/18947/pg18947-images.html

The Project Gutenberg ebook of the Younger Edda: Also Snorri’s Edda or The Prose Edda (by Snorri Sturleson). Scott, Foresman, & Co.

” In Norse mythology, Ragnarök is a foretold series of impending events, including a great battle in which numerous great Norse mythological figures will perish (including the gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdall, and Loki); it will entail a catastrophic series of natural disasters, including the burning of the world, and culminate in the submersion of the world underwater. After these events, the world will rise again, cleansed and fertile, the surviving and returning gods will meet, and the world will be repopulated by two human survivors, Líf and Lífþrasir. Ragnarök is an important event in Norse mythology and has been the subject of scholarly discourse and theory in the history of Germanic studies.

The event is attested primarily in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th.” Retrieved July 18, 2023. Wikimedia).

Ragnarok or Twilight of the Gods as told by Mary Litchfield

Courtesy: Nationalmuseum. “https://collection.nationalmuseum.se/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=18253&viewType=detailView” is licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

“The Aesir (Gods) and all the Einherjar dress for war and advance on to the field. Odin rides in front of them. He wears a gold helmet and a magnificent coat of mail, and he carries his spear called Gungnir. He goes against the Fenriswolf with Thor advancing on his side. Thor will be unable to assist Odin because he will have his hands full fighting the Midgard Serpent. His death will come about because he lacks the good sword, and the one that he gave to Skirnir. By now the hound Garmn, who was bound in front of Gnipahellir, will also have broken free. He, the worst of he monters, will fight against Tyr. They will be the death of each other.

Thor will kill the Midgard Serpent, and then he will step back nine feet. Because of the poison the serpent spits on him, he will fall to the earth dead.” (Byock, 2005, Sturluson, Prose Edda, p. 73).

Heimdall

Heimdall was the Norse god of prophecy and perception. He had keen eyesight and hearing; he was thought to possess enigmatic qualities. At Ragnarok, Heimdall kills the wolf Fenrir to avenge Odin’s death. “With one hand he takes hold of the wolf’s upper jaw and rips apart its moutn, and this will be the wolf’s death. Loki will battle with Heimdall, and this will be the death of each other” (Byock, 2005, p. 73).

Gimle (Gimli) : Hope, Regeneration, and Renewal

The Norse myths were influenced by Christian and Celtic texts. The idea of redemption, renewal, and transcendence from the earthly realm to a divine spiritual realm figured into the Norse poetry and sagas. Similarities can be found in terms of the stories of the creation as well as the apocalypse and Ragnarok depictions.

A new life characterized by harmony, peace, abundance and the absence of violence and strife is depicted. For the Norse people, Gimle was associated with a heavenly realm (retrieved September 3, 2022. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28497/28497-h/28497-h.htm)

In Myths of the Norsemen Helen Guerber (1909) explains:

“Our ancestors believed fully in regeneration, and held that after a certain space of time the earth, purged by fire and purified by its immersion in the sea, rose again in all its pristine beauty and was illumined by the sun, whose chariot was driven by a daughter of Sol, born before the wolf had devoured her mother. The new orb of day was not imperfect, as the first sun had been, and its rays were no longer so ardent that a shield had to be placed between it and the earth. These more beneficent rays soon caused the earth to renew its green mantle, and to bring forth flowers and fruit in abundance. Two human beings, a woman, Lif, and a man, Lifthrasir, now emerged from the depths of Hodmimir’s (Mimir’s) forest, whence they had fled for refuge when Surtr set fire to the world. They had sunk into peaceful slumber there, unconscious of the destruction around them, and had remained, nurtured by the morning dew, until it was safe for them to wander out once more, when they took possession of the regenerated earth, which their descendants were to people and over which they were to have full sway.

“We shall see emerge

From the bright Ocean at our feet an earth

More fresh, more verdant than the last, with fruits

Self-springing, and a seed of man preserved,

Who then shall live in peace, as then in war.”

Gimle, the highest heavenly abode.

When the small band of gods turned mournfully towards the place where their lordly dwellings once stood, they became aware, to their joyful surprise, that Gimli, the highest heavenly abode, had not been consumed, for it rose glittering before them, its golden roof outshining the sun. Hastening thither they discovered, to the great increase of their joy, that it had become the place of refuge for all the virtuous.”

“In Gimli the lofty

There shall the hosts

Of the virtuous dwell,

And through all ages

Taste of deep gladness.”

From: H.A. Guerber (1859-1929) Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas. Project Gutenberg ebook (originally published in 1909).

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/28497/pg28497-images.html.

Public Domain.

Courtesy: Gift of C.C.A. Baron du Bois de Ferrières, Cheltenham. “http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.12058” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

For more information about this painting, please open the link to the Mauritshuis Museum below: