11 Introduction: Mythic Monsters and Connections to Our Lives

“Myths are universal and timeless stories that reflect and shape our lives — they mirror our desires, our fears, our longings, and provide narratives that attempt to help us make sense of the world.”– Karen Armstrong, A Short History of Myth (2006)

“No matter how we define our ethnicity or culture, mythic creatures dwell somewhere within our psyches. Dragons, almas, jinn, sea serpents of all kinds, enticing maidens, chimeras, and more are present and real in cultures around the world.” (Kendall, Norell and Ellis, 2016, p. 5).

Epic tales, legends, myths, and folklore have all produced visions of strange and unusual creatures; these fragments of the imagination are also rooted in the reality of the diverse animal kingdom. Kendall, Norell and Ellis (2016) link mythic creatures to the “impossibly real” animals who inspired travellers and chroniclers of the natural world. The ordinary is mingled with the extraordinary, mystical, and uncanny. “We share the land with countless living animals; others seem quite bizarre. Creatures from the lands of myth can be both recognizable and strange. Sometimes they appear t have body parts from ordinary animals combined in very unusual ways. Other times they look just like familiar animals — but have extraordinary and magical powers” (p. 49).

As you look at the different mythic monsters and fantastical creatures in this unit, you can explore the ancient origins of one of the monsters/creatures that you find most interesting. You can explore the historical roots of ancient and modern myths and perhaps be inspired to write and draw your own unique stories, artwork, and multi-modal projects. To what extent is the monster based on actual animals and experiences that individuals had with them? What does the animal symbolize? To what extent is the animal/creature rooted in distinct personality traits and values? Are any of these creatures symbols of transformation, regeneration, and strength?

Through voyages of exploration and conquests that devastated many animal populations worldwide, so much was unknown about the different animals. They were viewed as a threat that would pose harm and destruction. The human world infringing on the natural world has caused untold havoc and destruction of the natural world. The vivid array of so many different monsters in the myths also reflects the diverse animals and creations in nature. So many myths were grounded in the unknown. At a time now when so many animal species have become extinct and are now endangered and threatened, author Brenda Rosen (2009) writes, “exploring the wealth of creatures imagined by cultures around the world deepens our connection to the natural world and strengthens our commitment to diversity and an abundant ecological future” (p. 10). Rosen further emphasizes that it is erroneous to associate monsters and fantastical creatures with ancient history. She writes:

The marvelous beings that pervade today’s fantasy novels and manga comics, role-playing video games, TV shows, and popular movies, are modelled closely on the creatures of traditional mythology and folklore….Mythic creatures can also help you to understand yourself. Fabulous creatures are often symbolic of human traits, both our divine qualities and the shadowy parts that we despise and fear. For this reason, imaginary beings fill our dreams and haunt our nightmares, carrying messages from our inner world… Semi-divine heroes and heroines, nature spirits, and supernatural beings that are told in every culture can rekindle your sense of wonder and deepen your faith. (p. 10-11).

A closer look at the real and imagined nonhuman creatures in myths can provide an insight into our personal and collective beliefs and values. Mythmaking, as Roukes (1982) notes, reflects an individual’s ability to create a unique type of story using imaginative imagery. A study of myths and mythic journeys can lead to self-discovery, spiritual insights, and creative learning. Karen Armstrong (2005) emphasizes that myths are universal story that reflect and shape our lives; they reflect our hopes, fears, and dreams. Each myth is a narrative story can be viewed as a guide to live more richly in a complex world. The heroes, monsters, supernatural events as well as the pantheon of gods, goddesses, muses, monsters, demigods, forest deities, fairies, sprites, centaurs, and centauresses symbolize aspects of the psyche and the human condition. Armstrong writes:

Our modern alienation from myth is unprecedented. In the pre-modern world, mythology was indispensable. It not only helped people to make sense of their lives but also reealed regions of the human mind that would otherwise have remained inaccessible. It was an early form of psychology. The stories of gods or heroes descending into the underworld, threading through labyrinths and flighting with monsters, brought to light the mysterious workings of the psyche, showing people how to cope with their own interior crises. When Freud and Jung began to chart the modern quest for the soul, they instinctively turned to classical mythology to explain their insights, and gave the old myths a new interpretation (2005, p. 11).

Armstrong (2005) makes an important point in stating that that even 100 or 200 years ago, mythology was viewed as “indispensable” in understanding history, culture, and the human condition. The imaginative and beautiful art created by Virginia Frances Sterrett, Henry Justice Ford, Frederick Stuart Church, and Arthur Rackham brought the myths and legends to life in intricate detail. The mythology collections of writers such as H.A. Guerber, Thomas Bullfinch, Snorri Sturleson, and Edith Hamilton can be revisited through a new learning lens in 2023. Their ideas can be catalysts for creative and imaginative learning. Each myth and mythic monster can also be explored from a social, cultural, and history lens or a psychological and philosophical lens. In an attempt to understand (and too often control, exploit, or even destroy) the natural world, explorers, writers, and artists depicted the non-human world in extraordinary ways.

Historical Books about Mythical Creatures

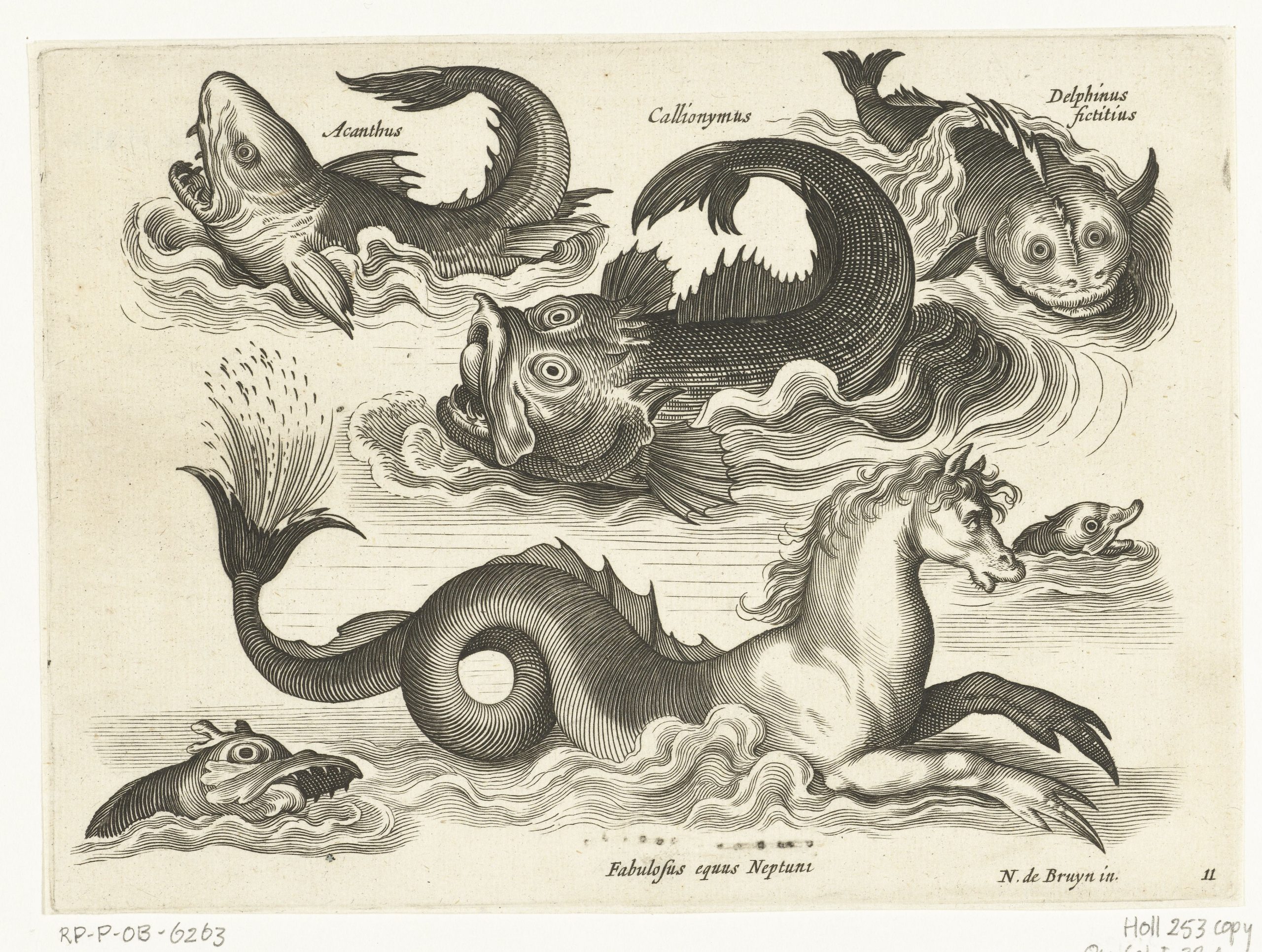

A source for the fabulous monsters derives from bestiaries, antique illustrative compendiums of the phenomena in the natural world. These books became more prominent in the middle ages; scholars began to observe, identify, classify, and categorize different animals. Rooted in antiquity, bestiaries are among the oldest illustrative compendiums of the natural world. Not all of these animals were based on empirical observations. Griffins, unicorns, giant sea serpents, dragons, and so on were often included alongside existing animals. Sometimes distinctions were not drawn between them and readers were often left to speculate as to whether a particular being was imagined or actual. (University of Connecticut analysis of Joannes Jonstonus Historiae Naturalis, 2022).

This section includes many illustrations, engravings, and art images of paintings of artists who were inspired by myth, legend, folklore, epic poetry, and classical and biblical texts. Selected images are complemented by poetry and prose. Links to learning resources are also provided for further research, inquiry, and exploration.

Adapted from Bartlett, S. (2015). The secrets of the universe in 100 symbols (p. 50-51) Chartwell &

Additional Sources:

Kendell, L., Norell, M.A., & Ellis, R. (2016). Mythic creatures and the impossibly real animals who inspired them. American Museum of Natural History.

|

Name |

Description |

Myth/Legend/Folktale |

Culture |

|

Alkanost |

A mythological creature with the head and chest of a woman and the body of an owl or other bird. |

In Russian fairy tales and folklore, the Alkanost’s beautiful voice made people forget their hardships and worries. These bird-women were said to possess magical powers. |

|

|

Centaurs and Centauresses |

Part human and part horse. |

Said to be the offspring of Xion, King of the Lapiths, and a cloud that Zeus created in the form of a goddess. |

|

|

Chimera |

A mythic fire-breathing creature that is parts lion, goat, and snake. |

Usually depicted as a lion with the head of a goat and the tail of a snake, the chimera was the offspring and Typhon (a monstrous serpentine snake) and Echidna (a half-woman, half snake-like creature). Chimera’s sibling was the three-headed dog of Hades, Cerberus. |

|

|

Minotaur |

Half man and half bull. |

In Greek mythology, the minotaur was a human-flesh-eating monster imprisoned in a labyrinth. King Minos’s wife Pasiphae falls in love with a bull; their offspring was the Minotaur. In avenging the death of his son, King Minos declared war on King Aegeus of Athens. Minos won the war and then demanded the annual sacrifice of fourteen people to feed the Minotaur. The Greek hero Theseus kills the Minotaur and liberates the people of Greece. |

|

|

Gorgon |

Gorgons were female monsters often featured with hideous faces and hair made of snakes. A glance at a gorgon would turn the onlooker into stone. The symbolism of Medusa (protective fighting spirit, destructive force, victim of Athena’s curse) is open to interpretation. |

Medusa is the most famous of the gorgons; she was once a beautiful woman who had been transformed into a monster by Athena. The Greek hero Perseus killed Medusa and then later used her head as a weapon that would shield him from enemies. |

|

|

Griffin |

Fantastical hybrid creatures that were said to nest in mountains; they had the head, torso, and talons of an eagle (or peacock), the body of a lion and are almost always featured with brightly coloured wings. |

Books such as C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland featured griffins. They are often associated with majesty, nobility, and power, but depending on the culture and context, a griffin’s symbolism can vary considerably. |

|

|

Hydra |

A mythic Greek water monster with multiple heads. |

The hydra regenerated multiple heads and for every head slain, two or three more grew back. The hydra had a poisonous breath and venomous blood. In the epic story of Buddha, the Mucalinda was the king of the Nagas, snake-like deities. The multi-headed Mucalinda protected the Buddha from storms and other harsh natural elements after he achieved enlightenment. Art works and statues of the Buddha often feature the Mucalinda “halo” of protection.

|

|

|

Dragon |

Enormous serpent-like creatures that may have wings and breathe fire. Dragons may also be multi-headed. Depending on the culture, dragons are composites of different animal characteristics but they are imbued with magical powers. In European legends and myths, dragons often live inside caves or near marshes. In early maps, images of dragons were often features to indicate dangerous or perilous waters. They also appear on emblems of authority like banners and seals. |

Depending on the culture, dragons are associated with life-affirming or life-destroying qualities. Some European stories feature a massive snake or lizard-like creature called a Basilisk that could cause men to die with a simply a glance. Greek and Nordic myths often feature the hero (such as Heracles) battling the multi-headed Lernean Hydra in pursuit to destroy a dragon that represent a threat or evil force. The legend of St. George and the Dragon is depicted in many works of art.

|

|

|

Thunderbird |

The Thunderbird is a legendary creature in North American Indigenous traditions, often depicted as a large raptor with horns, long legs, a wide wing span, and a featherless head. In some Indigenous legends, the thunderbird’s wings caused thunder and stirred the wind. Lightning derived from the thunderbird’s eyes. Thunderbirds belonged to “upper” spiritual realms; the visionary artist Norval Morrisseau (known as “Copper Thunderbird”) often featured mystical lynx and thunderbird spirit animals in his paintings. Morrisseau expressed his mystical beliefs on canvas. |

The Thunderbird was often associated with supernatural powers and thought to carry messages from Creator. Lightening was created with light from the Thunderbird’s eyes. |

|

|

Serpents and Sea Monsters |

Serpents are features in most world mythologies and belief systems. Sea monsters and sea dragons can have snake-like features. They inhabit the ocean and are found in many mythologies worldwide, and in particular in countries near seas and oceans. |

In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr was an enormous sea serpent that surrounded the earth. Causing havoc and destruction, Jörmungandr is killed by Thor (god of Thunder) at Ragnarok. The Loch Ness Monster and the Gloucester Sea Serpent are creatures found in Scottish and British folklore. Many sea serpents have their origins in real animals. |

|

|

Mermaids and Mermen |

Legendary beings often illustrated as half fish and half human. They are sometimes featured as companions to other water beings/spirits, such as Poseidon, and could be protective of sailors. |

Often depicted as “fatally attractive” and could lure men to their underwater homes; Mermen were the male counterpart to the mermaids. |

|

|

Unicorn |

A solitary, elusive, and mystical horse-like (or goat-like) creature with a single horn (Monoceros) that is sometimes a long spiral horn while in some ancient texts the horn is shorter. A unicorn’s horn is said to have magical properties. Unicorns are often white (sometimes brown or yellowish red) with the tail of a lion, goat, or boar, and reside in the deep woods. |

The famous “The Lady and the Unicorn” tapestries at the Cluny Museum in Paris represent allegories of love and emotion. Unicorns are often associated with love, purity, and mysticism. The unicorn is often viewed as a solitary animal and is a symbol of uniqueness and rarity. |

|

|

Sphinx |

A mythic creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of a falcon or other bird. |

For dynastic pharaohs in ancient Egypt the tradition was to carve the reigning monarch’s face onto a lion’s body at the tomb location. The sphinx was seen as both the source of wise, divine power with which the pharaoh ruled and served as the guardian of the pharaoh’s tomb. |

|

|

Phoenix, Firebird; Garuda; Simurgh; Feng Huang |

A mythological bird with supernatural and transformative powers. |

It is symbolic of rebirth and regeneration, arising from its own ashes to be reborn. |

|

|

Fauns, Nyads, and Satyr |

Part deer, part human. The Satyr is part human and part goat or other animal hybrid. |

Mythological forest deities or beings with magical powers. Satyrs haunted the woods and mountains; they were companions to Pan and part of the cult of Dionysus (Bacchus), the God of wine-making, vegetable, festivity, and harvests. |

|

|

Magical Horses |

Horses with wings and/or with multiple legs and other extraordinary features.

|

Magical horses like Pegasus (Greek mythology), Sleipnir (eight-legged horse of Norse mythology), and Hippocampus (the sea horse that pulled Poseidon’s chariot) are associated with speed, power, and protection. |

|

|

Trolls and Giants |

Imaginary creatures that lived in wooded areas, mountains, and on islands. In Icelandic folklore, the trolls were called huldefolk (little folk) and the giants were called jontars. Both possessed supernatural powers. |

In Norse myths, giants feature prominently in the early stories of creation. Parts of the giant’s body were used to form the earth and first peoples. Ymir Ymir was known to be the very first giant. |

|

|

Angelic Beings |

Divine beings of the heavens or cosmos (not always male or female) with supernatural powers. |

Spiritual, winged beings that assist God or serve as messenger or protector. |

|

Hoping to warn the city of Troy that the Greeks (the Spartans in Homer’s The Iliad ) were bringing the “gift” of a Trojan horse that was actually filled with warriors, Laocoön and his sons are attacked by giant serpents sent by the gods.

Classical References:

For complete references to The Odyssey and The Iliad (the art images are directly related to the descriptions in Homer’s epic texts), please see Samuel Butler translations (2022) and Alexander Pope translation of The Iliad (2022).

Albertus Seba’s Cabinet of Wonder and Awe (Biodiversity Heritage Library)

“Contrary to what one might think, a curiosity cabinet is not a piece of furniture, rather it is an entire room(s) dedicated to the collection of objects that are meant to bring shock, awe, inspiration, and stimulating conversation to its viewers. During the 16th-19th centuries, the curiosity cabinet became a popular way for aristocrats and aspiring bourgeoisie to show off personal wealth and erudition. These “rooms of wonder” are considered the precursors to the modern museum. However, unlike a museum collection that is organized around a specific theme e.g. archaeology, art, natural history, and sculpture, a cabinet of curiosities celebrates its own bedlam, juxtaposing disparate objects in a jumbled mass to prompt serendipitous discoveries, new connections, and eureka! moments about the manifest world. By the 18th century, order began to coalesce out of chaos and curiosity cabinets became a bit more focused. Such was the case with a famed apothecary from Amsterdam, Albertus Seba, and his cabinet of natural history curiosities. Today, we will examine what exactly was in Seba’s celebrated collection and see if we can still find hints of the fabulous, wondrous, exotic, and down-right strange.”

Further Resources:

“A Wonder Room – Every School Should Have One” by Chris Arnot (The Guardian, 2011)

You can find the complete text of The Red Book of Animal Stories here.

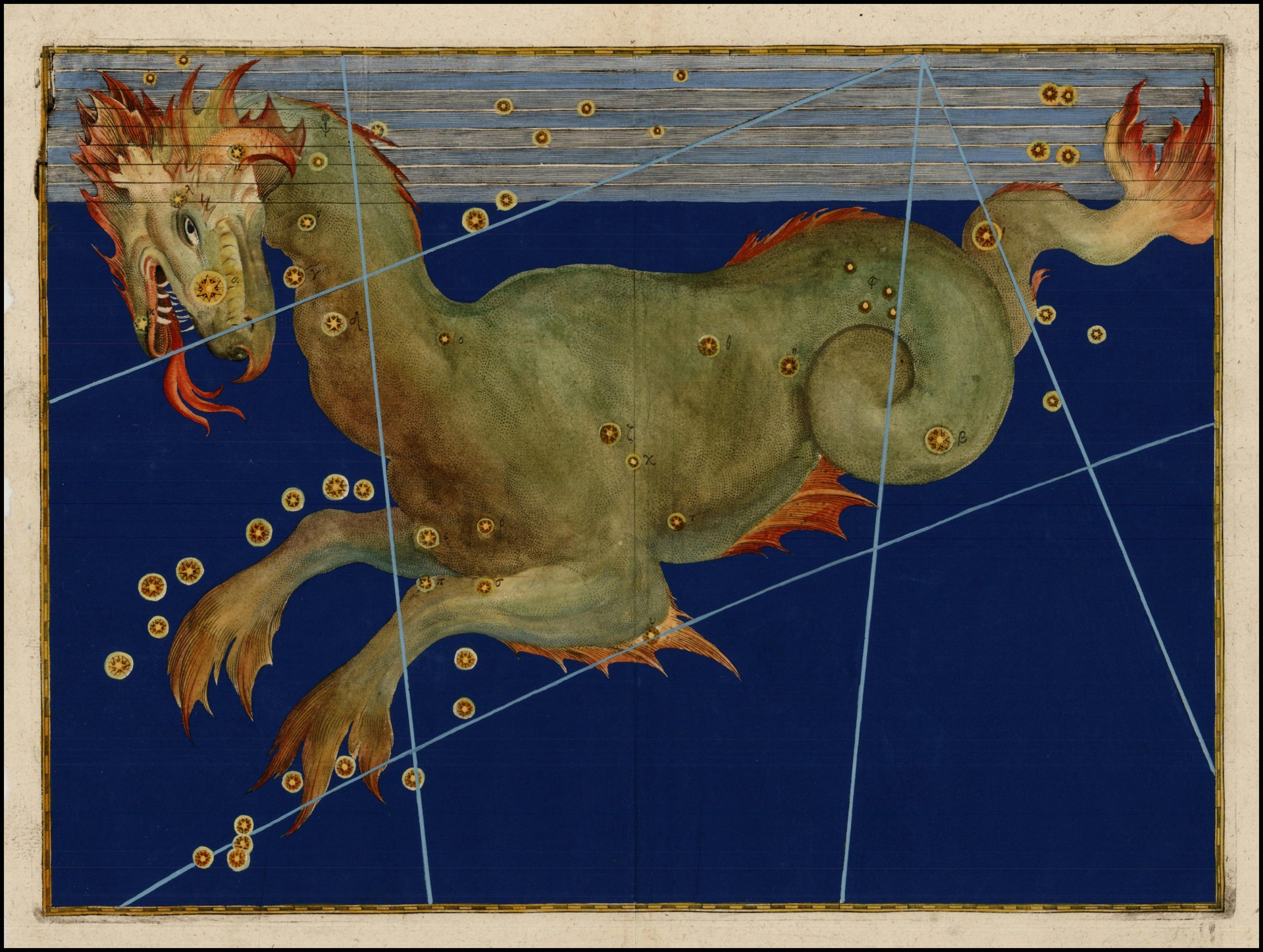

Johann Bayer’s Artistic and Imaginative Constellations

Johann Bayer (1572-1625) drew each constellation with a new method; the renderings were then engraved on copper plates. Being the first atlas to artistically chart the complete celestial sphere, The Unametria was published in Augsburg, Germany in 1603 by Christoph Mangle (Christophorus Mangus). The word “uranomatria” originates in the Greek word for Urania (the muse of the heavens) and “Uranos” (meaning sky or heavens). The word “matria” refers to measurement (hence the translation of Uranometria is “measuring the heavens”). Bayer’s art charted the constellations with fantastical creatures and deities.