1 Egyptian Myths and Stories of Creation

Egyptian Myths and Stories of Creation

The great Nile River in Egypt was the source of its rich civilization that spanned thousands of years. Described in hieroglyphics and other art images, the Egyptians conceptualized the beginning as a vast ocean of ‘Nun’ or nothingness. Order was created out of chaos. The creator god Atum (or Atum-Ra) emerged from the ocean of cast and from this the first Egyptian gods were created. Wilkinson et al, 2021 write:

Atum emerged from the chaos of Nun in whose waters he had dwelled inert. From his own body. He created other gods. From his nostrils Atum sneezed out Shu, the god of air, and from his mouth he spat out Tefnut, the goddess of moisture, sending both far across the water. Later, Atum sent his right eye, the sun, to look for Shu and Tefnut. This eye was the goddess Hathor, a devouring flame full of wild and unpredictable force. When she returned with Shu and Tefnut, she was angry with Atum for another eye had grown in her place. She wept bitter tears, which became the first human beings (Wilkinson, et al, p. 268).

A strong interconnection existed between religion and mythic stories. The Kings (Pharoahs) and queens of Egypt were considered human personifications of the gods and goddesses. These gods were thought to rule over different domains of life: birth, death, the household, cycles of nature, work, etc. There were over 1,500 deities with each having a specific role in the daily lives of ancient Egyptians (refer to Chart 1). Many animals such as the cat, lion, crocodile, hippopotamus, the cobra, falcon, and ibis were sacred. Ancient Egyptians believed that gods and goddesses were reincarnated as animals. Pyramids, temples and statues were created to commemorate these gods. Intricate hieroglyphics contained logographics (symbols/images representing words and morphemes) syllabic, and alphabetic characters revealed not only the daily lives of ancient Egyptians but these hieroglyphics often told the stories of the gods and goddesses. (Dersin, 1996).

Major Egyptian Gods from Wilkinson, et. al 2021 The Mythology Book (p.268). Penguin Random House

| Atum-The creator god, also known as the sun god Ra, or Atum-Ra |

| Shu-God of the Air |

| Tefnut-Goddess of Moisture |

| Hathor-The ye of Ra (in lioness form) called Sekhmet |

| Geb-God of the Land & Earth |

| Nut-Goddess of the Sky |

| Thoth-God of Reckoning |

| Osiris- King on earth; ruler of the Underworld |

| Horus-Son of Isis and God of the Sky |

| Seth-God of the desert and god of disorder and destruction |

| Isis-Goddess of marriage, fertility, and magic |

| Nephthys-Goddess of death and the night |

List to Egyptian Gods and Goddesses:

World History Encyclopedia

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/885/egyptian-gods—the-complete-list/#:~:text=The%20gods%20and%20goddesses%20of%20Ancient%20Egypt%20were,Anubis%2C%20and%20Ptah%20while%20many%20others%20less%20so.

John Frederick Lewis (1805-1876). On the Banks of the Nile, Upper Egypt, Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut.

Public Domain (died 1896) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Frederick_Lewis_-_On_the_Banks_of_the_Nile,_Upper_Egypt_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Courtesy: Yale Centre for British Art (Open Access) and Wikimedia Commons

“To the Nile” by John Keats (1795-1821)

Courtesy:

Son of the old Moon-mountains African!

Chief of the Pyramid and Crocodile!

We call thee fruitful, and that very while,

A desert fills our seeing’s inward span;

Nurse of swart nations since the world began,

Art thou so fruitful? Or dost thou begile,

Such men to honour thee, who, worn with toil,

Rest for a space ‘twixt’ Cairo and Decan?

O may dark fancies err! They surely do;

‘Tis ignorance that makes a barren was

Of all beyond itself. Thou dost bedew

Green rushes like our rivers, and dost taste

The pleasant sun-rise; Green isles hast thou too,

And to the sea as happily dost haste.

And to the sea as happily dost haste.

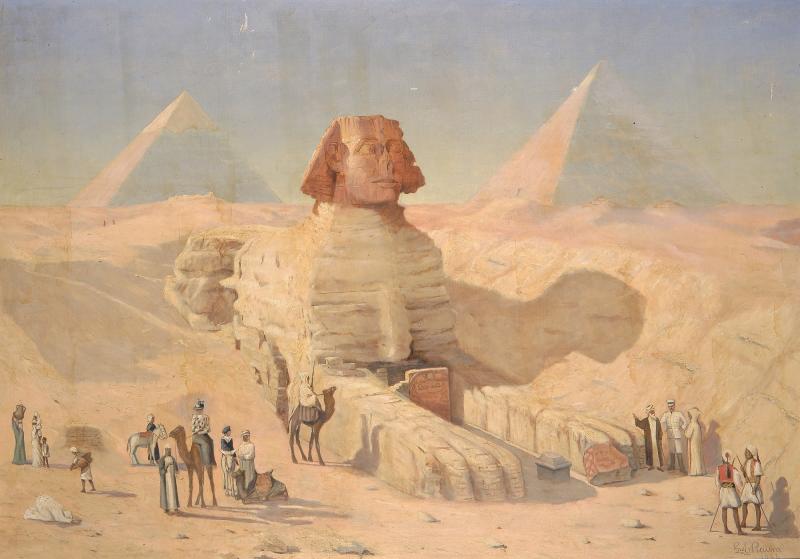

Courtesy: Smithsonian Art Museum, Washington, DC. Gift of the Artist. George E. Raum (1846-1922). The Great Sphinx of Giza (1896), Open Access.

The Sphinx – Mathilda Blind (English-German poet, 1839-1896).

Wanderer, behold Life’s riddle writ in stone,

Fronting Eternity with lidless eyes;

Of all that is beneath the changing skies,

Immutably abiding and alone.

The handiwork of hands unseen, unknown.

When Pharoahs of immortal dynasties

Built Pyramids to brave the centuries,

Cheating Annihilation of her own.

The heart grows hushed before it. Nay, methinks

That Man, and all on which Man wastes his breath,

The World, and all the World inheritor,

With infinite, inexorable links

Grappling the soul that love, hate, birth and death

Dwindle to nothingness before thee-Sphinx.

Form: Ryan, D.P. (2016). Ancient Egypt in poetry: An anthology of nineteenth-century verse.

American Univeristy in Cairo. p. 50.

Source: https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/sphinx-4

God Horus Protecting King Nectanebo II

Falcon God Horus God Horus Protecting King Nectanebo II, 360–343 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY.

Open Access, Public Domain https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544887

Wedjat Eye Amulet

Wedjat Eye Amulet (Eye of Horus). Ca. 1070-664 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY.

Open Access, Public Domain https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/561047

Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Open Access.

For more information about the Wedjat eye amulet, please click the link below:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/561047

To view more Egyptian Art, please look at the MET collection:

https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/egyptian-art

Metropolitan Museum of Art Information:

The Met collection of ancient Egyptian art consists of about 26,000 objects of artistic, historical, and cultural importance, dating from the Paleolithic to the Roman period (ca. 300,000 B.C.–A.D. 4th century). Many of the Egyptian artefacts derived from decades of archaeological works going back to 1906. These collections were, in part, a result of the increasing public interest about the culture, art, and history of ancient Egypt. Please refer to the links above and in the reference section for more information.

Statuette of Amun

Statuette of Amun (“the hidden one”), Statuette of Amun ca. 945–712 B.C. Third Intermediate Period, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY.

Open Access, Public Domain https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544874

Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art (open access), New York City, NY.

For more information on Egyptian art, please click the link below:

https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/egyptian-art

Head of the God Amun

Head of the god Amun, ca. 1336-1327 B.C. New Kingdom, post-Amarna Period, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Open Access, New York City, NY.

Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1907.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544691

Head of a Goddess

Head of a Goddess (New Kingdom), 1295-1270 B.C. . Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York. Open Access.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547704

Poetry Excerpt -Ancient Egyptian Love Poetry (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland)

She has no rival,

there is no one like her.

She is the fairest of all.

She is like a star goddess arising

… at the beginning of a new year;

brilliantly white, shining skin;

such beautiful eyes when she stares,

and sweet lips when she speaks;

she has not one phrase too many.

With a long neck and shining body

her hair of genuine lapis lazuli;

her arm more brilliant than gold;

her fingers like lotus flowers,

ample behind, tight waist,

her thighs extend her beauty,

shapely in stride

when she steps on the earth.

She has stolen my heart with her embrace,

She has made the neck of every man

turn round at the sight of her.

Whoever embraces her is happy,

he is like the head of lovers,

and she is seen going outside

like That Goddess, the One Goddess

A Journey Paved with Papyrus:

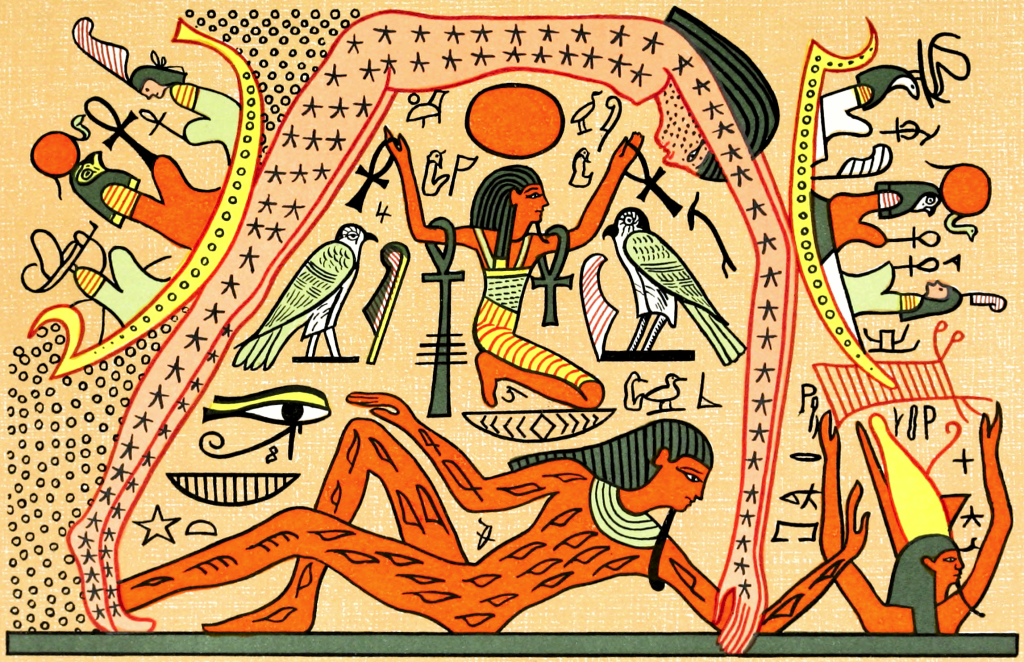

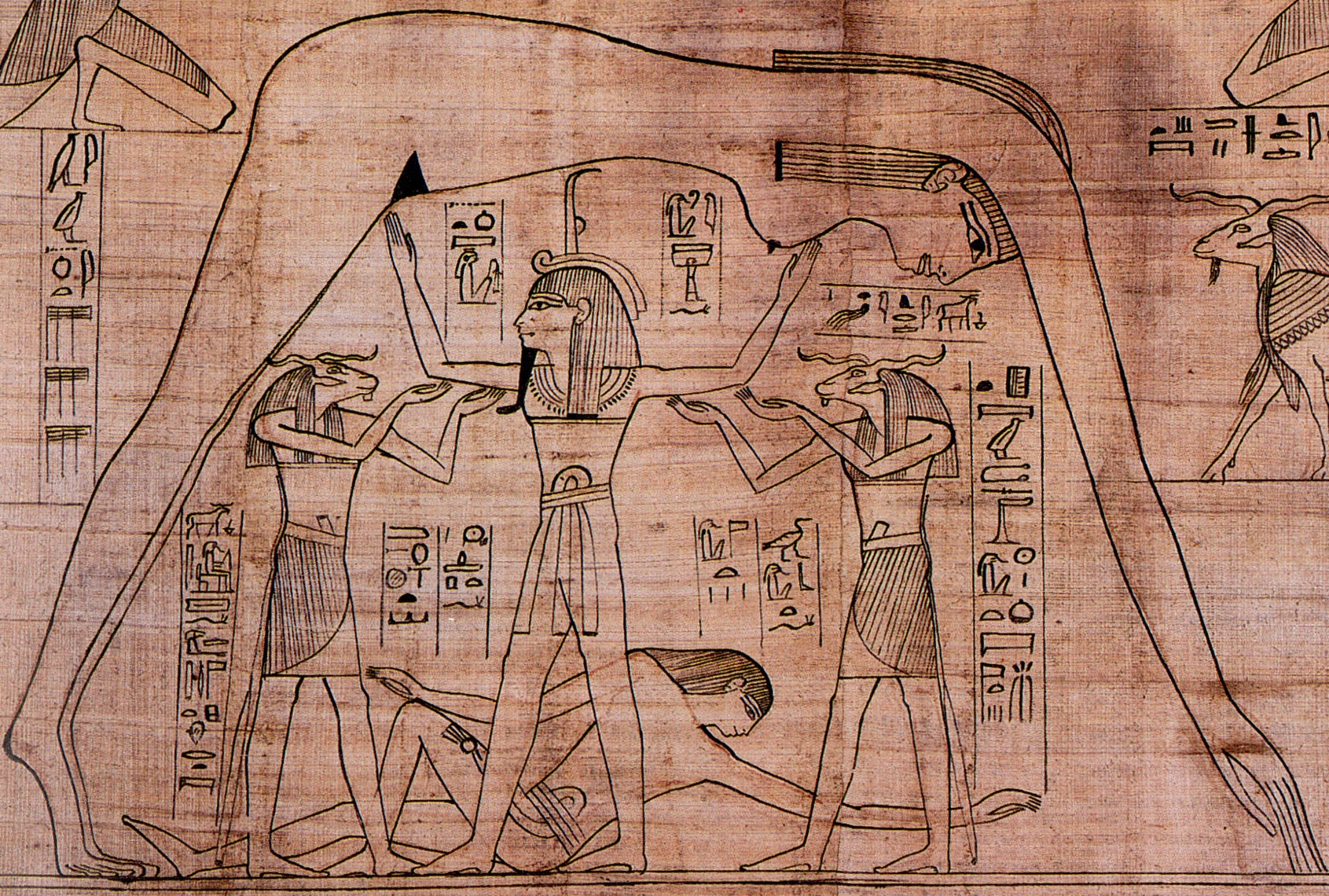

Seb (God of the Earth) Holding Up Nut (Goddess of the Sky) on Heaven

E. A. Wallis Budge (1857-1937) Seb (God of the Earth) Holding Up Nut (Goddess of the Sky) on Heaven. Colour Plate (1907). In The Gods of The Egyptians, Vol. 11. pg. 96. British Museum, London, UK.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geb_and_Nut03.png

Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

For more information about Egyptian gods and goddesses please refer see the link below to access The Project Gutenberg EBook of Legends of the Gods by Egyptologist E.A. Wallis Budge:

Isis and Horus

Isis and Horus (Late Period–Ptolemaic Period), 664-30 B.C. Coutesty of theMetropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Statuette_of_Isis_MET_66.99.121.jpg

Isis was known to be the Mother of all the Pharoahs. She is portrayed as a mother, wife, protectress, and a source of life. Along with Osiris and Horus, she was considered one of the major religious dieties.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545969

The Goddess Isis and her Son Horus

A Votary of Isis

Egyptian Goddess Isis. Portrait Painting. Edwin Long (1829-1891), A Votary of Isis, 1891. Southeby Art Catalogue. Courtesy: Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edwin_Long_-_A_Votary_of_Isis.jpg#/media/File:Edwin_Long_-_A_Votary_of_Isis.jpg

Statuette of Osiris

Statuette of Osiris, 664–332 B.C Late Period Dynasty 26-30. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Courtesy: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545802

Fragment of a Queen’s Face

Fragment of a Queen’s Face. Quarzite. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egyptian Galleries, 1390-1336 BC New Kingdom ( mid Dynasty 18 reign of Amenhotep III or Akhenaten). Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544514

She Walks in Beauty

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impaired the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress,

Or softly lightens o’er her face;

Where thoughts serenely sweet express,

How pure, how dear their dwelling-place.

And on that cheek, and o’er that brow,

So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow,

But tell of days in goodness spent,

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!

Source: The Complete Poetry by Lord Byron and The Poetry Foundation

She Walks in Beauty by Lord Byron (George Gordon) | Poetry Foundation

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes:

Sphinx Sculptures

Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharoah

Royals kings and queens in ancient Egypt were often equated with gods in human form. They were thought to possess super human qualities. Each king, for example, was the “son of God” and at death would be re-united with the father in a cosmic heaven. Pyramids, sphinx statures, and other artistic rendering were ways of honouring and protecting royal Egyptian monarchs. Hatshepsut (“foremost of the noble ladies”).

Hatshepsut was a female pharaoh; in this sphinx image, she has the body of a lion and a human head. Close artistic attention is paid to the power of the lion and the idealized face of the pharaoh.

Sphinx of Hatshepsut, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (1479-1458 B.C.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art (open access/public domain). Rogers Fund, 1931. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544442

The Female Pharaoh Hatshepsut

Statue of The Female Pharaoh Hatshepsut, New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (1479-1458 B.C.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Courtesy: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544849

This granite statue of Hatsheput dates back to the New Kingdom during the joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Hatshepsut wears feminine clothes but her headcloth is normally used for the reigning king. Her throne name is Maatkare and her titles include “Lady of the Two Lands” and “Bodily Daugher of Re.”

For more information and learning resources, please open the Metropolitan Museum of Art link below:

Senwosret III as Sphinx

Senwosret III as a Sphinx. 1878-1840 BC. Sphinx. Courtesy: Egyptian Galleries, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Rogers Fund, 1929, Torso lent by Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (L.1998.80). https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544186

Sphinx of Senwosret

Because of their strength, ferocity, imposing mane, and awesome roar, lions were associated with associated with strength and ferocity. They were often associated with gods and goddesss. In cosmic myths of creation, they were associated with the sun and the horizon. Lions were a protective symbol against evil. Distinct images of the sphinx (body of the lion and head of a human) were often created to resemble the reigning monarchs.

As travel began to expand in the 19th century, historians, artists, educators, etc. began to travel the ancient cities of Egypt. Many wrote eloquent poems inspired by the Egyptian monuments, statues, and art they saw:

“Egypt! From whose all dateless tombs arose Forgotten

Paroahs from their long repose. And shook within

Their pyramids to hear a new Cambyses thundering

In their ear. While the dark shades of forty ages stood

Like startled giants by Nile’s famous flood.”

Ancient of Days! Before the Trojan Wars

You towered as now in your colossal prime,

Watching the rosy footed morning climb

O’er far Arabia’s flushing mountain bars.

Despite your weird disfigurement and scars

You dwarf all other monuments. Sublime

Survivors of old Thebes! you baffle Time,

And sit in silent conclave with the Stars.

Ah, once below you through the glittering plain

Stretched avenues of Sphinxes to the Nile;

And, flanked with towers, each consecrated fane

Enshrined its god. The broken gods lie prone

In roofless halls, their hallowed terrors gone,

Helpless beneath Heaven’s penetrating smile.

By Mathida Blind:

https://theotherpages.org/poems/blind02.html

Coffin of Nesykhonsu

Coffin of Nesykhonsu, Egypt Third Intermediate Period, late Dynasty 21 (1069-945 BC)-early Dynasty 22 (945-715 BC), Thebes.

Courtesy: Cleveland Museum of Art (open access). Artstor. Coffin of Nesykhonsu (lid) on JSTOR

Funerary Mask

Funerary Mask. Mummy Head Cover, Roman Period 1st Century BC (Ptolemaic Period, 332-3- B.C). Courtesy: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/64315/mummy-mask

To an Egyptian Mummy by Horace Smith (1779-1849)

AND thou hast walked about—how strange a story!—

In Thebes’s streets, three thousand years ago!

When the Memnonium was in all its glory,

And time had not begun to overthrow

Those temples, palaces, and piles stupendous,

Of which the very ruins are tremendous!

Speak! for thou long enough hast acted dummy;

Thou hast a tongue,—come, let us hear its tune!

Thou ’rt standing on thy legs, above ground, mummy

Revisiting the glimpses of the moon,—

Not like thin ghosts or disembodied creatures,

But with thy bones, and flesh, and limbs, and features!

Tell us,—for doubtless thou canst recollect,—

To whom should we assign the Sphinx’s fame?

Was Cheops or Cephrenes architect

Of either pyramid that bears his name?

Is Pompey’s Pillar really a misnomer?

Had Thebes a hundred gates, as sung by Homer?

Perhaps thou wert a mason, and forbidden,

By oath, to tell the mysteries of thy trade;

Then say, what secret melody was hidden

In Memnon’s statue, which at sunrise played?

Perhaps thou wert a priest; if so, my struggles

Are vain, for priestcraft never owns its juggles!

Perchance that very hand, now pinioned flat,

Hath hob-a-nobbed with Pharaoh, glass to glass;

Or dropped a halfpenny in Homer’s hat;

Or doffed thine own, to let Queen Dido pass;

Or held, by Solomon’s own invitation,

A torch at the great temple’s dedication!

by Horace Smith

Inlay in the Form of the Horus Falcon

Inlay in the Form of Falcon Horus. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century B.C. Courtesy: Egyptian Galleries, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/551330

Inlay in the Form of Falcon Horus. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period, 4th Century B.C. Courtesy: Egyptian Galleries, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/551330

Inlay Depicting the “Horus of Gold” 4th Century BC

Many animals were sacred to the Egyptians. This inlay is a composite hieroglyph, termed the Horus of Gold: the falcon god Horus sits on top of the sign for gold, a collar with ties. This sign appears before one of the royal names, called the “Horus of Gold name.”

An Old Identity by Mohammad Harbi translated by Mohammad Salama

“A falcon, free, dreaming of becoming a light

a phantom searching for a bird

that lost form in an instant of sleep

a star shining in God’s direction….”To access the complete poem as well as others, please open the link below.

*Mohammad Harbi (1961-) is an Egyptian writer and journalist. To read more of his poetry, please access the link above.

Egyptian Estate Figurine

Egyptian Estate Figurine, 1981-1975 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, Open Access. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544210

1295-1270 BC

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes:

“This masterpiece of Egyptian wood carving was discovered in a hidden chamber at the side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the royal chief steward Meketre, who began his career under King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II of Dynasty 11 and continued to serve successive kings into the early years of Dynasty 12. Together with a second, very similar female figure (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo) this statue flanked the group of twenty two models of gardens, workshops, boats, and a funeral procession that were crammed into the chamber’s narrow space. The woman is richly adorned with jewelry and wears a dress decorated with a pattern of feathers, the kind of garment often associated with goddesses. Thus, this figure and its companion in Cairo may also be associated with the funerary goddesses Isis and Nephthys who are often depicted at the foot and head of coffins, protecting the deceased” (Retrieved July 14, 2023 Estate Figure | Middle Kingdom | The Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org))

Animal Images in Ancient Egypt: Connections to Deities

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/animals-of-ancient-egypt.html

William the Hippo

William the Hippo, 1961-1978, Courtesy: The Metropolian Museum of Art, New York, Egyptian Galleries. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544227

Symbolism of the Hippopotamus in Ancient Egypt

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes:

“To the Egyptians, the hippopotamus was viewed as a symbol of protection, strength, and rebirth. William the hippo was molded in the cermanic quartz stone known as “faience.” The hippo is painted with lotus flowers, another symbol of regeneration and rebirth.To the ancient Egyptians, “the hippopotamus was could be a fierce and dangerous animal. Small fishing boats could be damaged and destroyed if they encountered a hippo in the waterways. The hippo was an important animal both on on the earthly plane and in the afterlife….The Egyptians also worshipped the hippo in the form of the Egyptian goddess, Tauret (“she who is great”). Often represented as a female pregnant hippopotamus, the Egyptians regarded Tauret as the goddess of fertility; she was said to protect pregnant women. “(Metropolitan Museum of Art, notes Retrieved September 3, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544227).

Osiris (God of Fertility) and the Four Sons of Horus

Osiris (God of Fertility) and the Four Sons of Horus, 1400-1352 B.C. New Kingdom. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Art Fund (Creative Commons). https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548563

Nut-Egyptian Goddess of the Sky

Learning Objectives

For more Egyptian art please follow the link below:

Head of Osiris

Head of Osiris (Fertility God and God of Agriculture) wearing Atef Crown | Late Period (Saite), Dynasty 26. Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Head of Osiris wearing an Atef Crown, 600-550 BC. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547700

Key Takeaways

For more information about Egyptian Creation Myths, please open the link below:

https://www.tripsinegypt.com/ancient-egyptian-creation-myth/

Bastet, The Cat Goddess

Bastet, The Cat Goddess. 664–30 B.C.. Gift of Florence Blumenthal, 1934. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/551774

To the ancient Egyptians, cats were symbolic of beauty, strength, and agility. Bastet was a powerful cat-headed goddess known for her fertility. She was viewed as a protector of pregnant women and temples and statues were created to honour her. In Bubastis (Nile Delta region) , a discovery was made of thousands of cat mummies as well as cat statues. The cult devoted to Bastet was most popular during the Late and Ptolemaic Periods (Metropolitan Museum of Art notes). The Egyptian cat which was considered a sacred animal was larger than most domesticated cats that we would be familiar with today. The cat statue featured above was made from leaded bronze, precious metal and black bronze inlay

Open Access Collection:

Cat statuette intended to contain the remain of a mummified cat, 332-30 BC

The

Cosmetic Vessel in the Shape of a Cat

Cosmetic Vessel in the Shape of a Cat, 1990-1980 B.C., Middle Kingdom.

Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. NY. Egyptian Galleries. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544039

Metropolitan Museum of Art Notes: “The cat first appears in painting and relief at the end of the Old Kingdom, and this cosmetic jar is the earliest-known three-dimensional representation of the animal in Egyptian art. The sculptor demonstrates a keen understanding of the creature’s physical traits, giving the animal the alert, tense look of a hunter rather than the elegant aloofness seen in later representations. The rock-crystal eyes, lined with copper, enhance the impression of readiness”( Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. NY. Egyptian Galleries. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544039

To a Sacred Cat by Mary Mapes Dodges

Long, long ago, in Egypt land,

Where the lazy lotus grew,

And the pyramids, though vast and grand,

Were rather fresh and new,

There dwelt an honored family,

Called Scarabéus Phlat,

Whose duty ’t was all faithfully

To tend the Sacred Cat.

They brought the water of the Nile

To bathe its honored feet;

They gave it oil and chamomile

Whene’er it deigned to eat,

With gold and precious emeralds

Its temple sparkled o’er,

And golden mats lay thick upon

The consecrated floor.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Mapes_Dodge

https://nickyvandebeek.com/2018/01/ancient-egypt-in-19th-century-poetry/

Selection of Scarabs

Selection of Scarabs, The Middle Kingdom. Dynasty 12 (1981-1802 B.C.). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. NY. Egyptian Galleries. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/688614. Public Domain.

Winged Scarab

Winged Scarab, 664-332 B.C.E. Faience, 1/2 x 1 1/16 x 1 5/16 in. (1.2 x 2.7 x 3.3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Egypt Exploration Fund, 15.523. (CC BY-4.0). (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, CUR.x249.42_wwgA-3.jpg). https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/119440

Amunhotep III

Amunhotep III, ca. 1390-1352 B.C.E. Wood, gold leaf, glass, pigment, Total height: 10 3/8 in. (26.3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 48.28. Licensed under (CC BY-4.0). (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 48.28_front_PS4.jpg). https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3496

Mummy Mask

Unidentified, Mask, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.8.618.2 . Licensed under (CC0 1.0). (Original submission: https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/mask-31154).

Examples of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses Smithsonian American Art Museum

Death and the Afterlife:

To ancient Egyptians, death was not viewed as an end but rather a transition to a rich afterlife. The process of embalming was left to the high priests. Some Egyptologists maintain that the preoccupation of death rituals and the afterlife may have been a factor that led to the ultimate decline of the Egyptian dynasties. The mummy masks were composed of linen, plaster, and wood. Elaborate preparations and precautions were taken to ensure that the individual would be welcomed into the afterlife. Food, cosmetics, tools, jewellery, and furniture surrounded the body.; The Egyptians believed that Ra the sun god had a body of solid gold; as a result, the gold gilding of mummy masks became symbols of light and divinity.

“Bodies were prepared to receive the ba, or spirit, and a mask would be placed over the head and shoulders of the mummy so that the spirit could recognize its host. The mask did not present a portrait of the individual, but instead showed a youthful, idealized image of what he or she would look like in the next world.” (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC). Retrieved August 27, 2022 https://www.si.edu/object/mask:saam_1929.8.618.2

Courtesy: Smithsonian Art Museum.

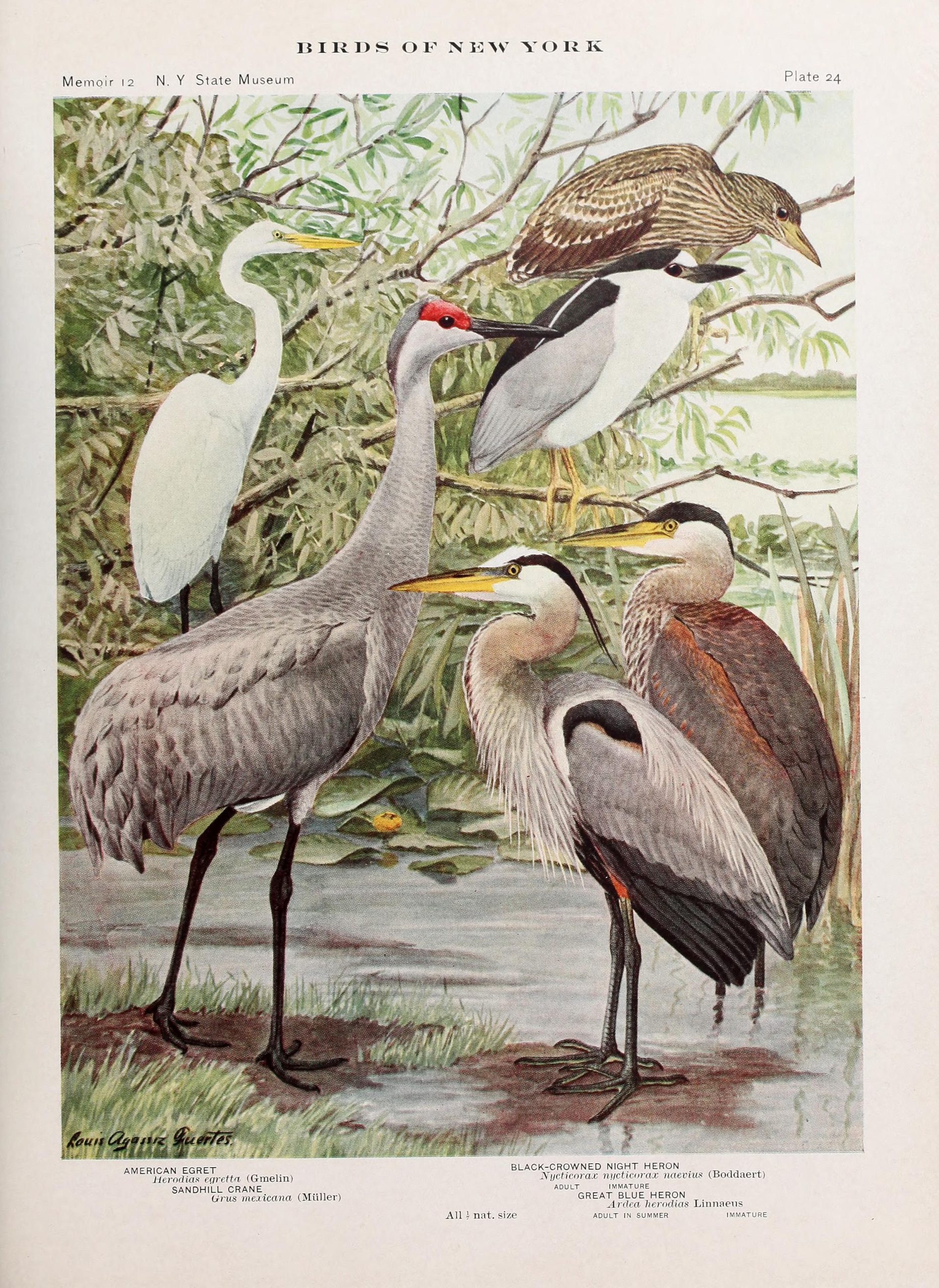

Egyptian Birds Seen in the Nile

In ancient Egypt, birds were often viewed as symbols of rebirth and regeneration. The heron represented prosperity and was often associated with the Sun God Ra.

Relief Fragment of Grey Heron

Relief Fragment with Two Birds in the Papyrus Thicket, ca. 1925–1900 B.C. Egyptian, Middle Kingdom Limestone, paint; H. 18.5 cm (7 5/16 in.); W. 25.5 cm (10 1/16 in.); D. 5.5 cm (2 3/16 in.). Public Domain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1913 (13.235.9). http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/556809

White Heron on the Water’s Edge

White Heron on the Water’s Edge, Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Public Domain. Brooklyn_Museum_-_White_Heron_at_Water’s_Edge_-_Kason.jpg (768×722) (wikimedia.org)

The Bennu Heron

Bennu Bird, By Jeff Dahl – Own Work, (CC BY-SA 4.0), Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain/Open Access. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3293473

The Bennu was a larger type of Heron Bird which is now extinct. The Egyptian Associated the Bennu and the Phoenix with resurrection and the after life. The bennu bird, an ancient Egyptian deity often depicted as a heron wearing the atef crown. Based on New Kingdom tomb paintings.

Herons in Art

Louis Agassiz Fuertes, 1874-1927, Herons in Art. 1902. Illustration in an Annual Report. New York State Museum. University of the State of New York in Albany. https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14776626025/

Goliath Heron

Paul Manship, Angelo Colombo, Goliath Heron, 1932. Gilded Bronze on Lapis Lazuli base, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Artist, 1965.16.9. Public Domain. Goliath Heron | Smithsonian American Art Museum (si.edu)

Egyptian Ibis Bird

Derek Keats, Johannesburg, South Africa. 2018. Licensed under (CC BY 2.0). African Sacred Ibis, Threskiornis Aethiopicus, at Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:African_Sacred_Ibis,_Threskiornis_aethiopicus,_at_Pilanesberg_National_Park,_South_Africa_%2845081681391%29.jpg

The Ibis was a sacred bird to many Egyptians and was a symbol of resurrection.

T. Owen, An Egyptian Ibis Bird, 2018. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36544492

T. Owen, An Egyptian Ibis Bird, 2018. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36544492

Alethe, Attendant to the Sacred Ibis

Edwin Long, 1829-1891. Alethe, Attendant to the Sacred Ibis, 1888. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5a/Edwin_Longsden_Long_-_Alethe_Attendant_of_the_Sacred_Ibis_in_the_Temple_of_Isis_at.jpg

Limestone Relief of Birds in a Thicket

Birds in the Papyrus Thicket, ca. 2020–2000 B.C. Egyptian, Middle Kingdom. Limestone, paint; 18 7/8 x 37 3/8 in. (48 x 95 cm). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Egypt Exploration Fund, 1906 (06.1231.3a, b). Public Domain. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/545290

“The Ba is an aspect of a person’s spiritual being. After death, the Ba was able to travel out from the tomb, but it had to periodically return to the tomb and be reunited with the mummy. The ba was usually represented as a bird with a human head, and sometimes with human arms. (Metropolitan Museum of Art-Information Page).”

For more Information about the Ba-Bird and Meaning https://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/1993/11/01/ba-bird/

Egyptian Ba-Bird

Ba-bird, Ptolemaic Period, 332–30 BC or later. Wood, paint, gold leaf. Dimensions: H. 15.5 cm (6 1/8 in.); W. 5.1 cm (2 in.); L. 9.3 cm (3 11/16 in.). Credit to the Rogers Fund, 1944. Accession number: 44.4.83. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, NY. Public Domain.https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545942

The ba is an aspect of a person’s spiritual being. After death, the ba was able to travel out from the tomb, but it had to periodically return to the tomb and be reunited with the mummy. The ba was usually represented as a bird with a human head, and sometimes with human arms. (Metropolitan Museum of Art-Information Page) More Information about the Ba-Bird and Meaning https://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/1993/11/01/ba-bird/

Queen Cleopatra and Mark Anthony

Queen Cleopatra and Mark Anthony (1901) as imagined by German-born American artist Joseph Christian Leyendecker (1874-1951). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114016594

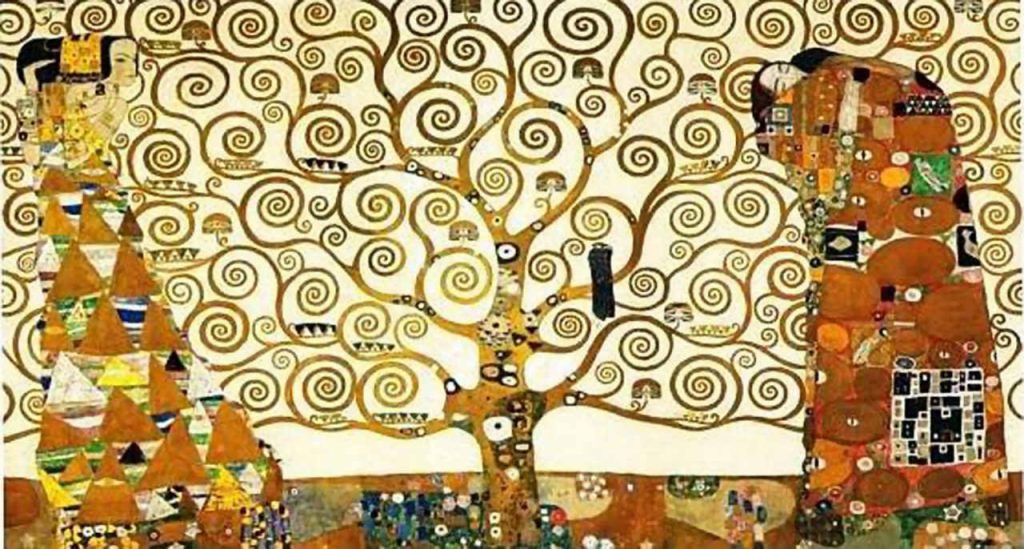

Egyptian Style Influence on Gustav Klimt’s The Tree of Life

Gustav Klimt, 1862-1918. Stolcet Frieze, The Tree of Life. 1909. Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Klimt_Tree_of_Life_1909.jpg

Klimt integrates Egyptian and Celtic design and art for this monumental Tree of Life frieze.

In an iconoclastic mural “The Tree of Life” (Stoclet Frieze) painted by the Austrian artist Gustav Klint, elements of Celtic and Egyptian design are featured. Motifs such as the Celtic swirls an the Egyptian eye combine to create a magnificent and enigmatic work that reflects life, death, love, and hope. The Egyptian eye of Horus represents health, rejuvenation, and healing while the Celtic circles and spirals throughout Klimt’s painting could symbolize he spirals are also said to symbolize spiritual, emotional, and physical self; the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth/transformation could also be symbolized by the swirls. Klimt was influenced by the rich decorative use that ancient Egyptian made of gold in jewellery and in the intricate gold leaf of royal furniture and mummies. The branches spiral and turn; a tapestry of long branches and vines symbolize life’s journeys its many thresholds and turning points . The branches reach toward the sky and the lovers’ embrace signifies the tentative and ephemeral nature of love. All that is born will find its way in the world and then return to its “roots” to die. For Klimt, the tree may symbolize love, wisdom, beauty, and strength. The black bird is often viewed in literature as harbingers of death. In the painting, the black bird is sitting on a branch, not far from the couple. Like a person striving to realize their dreams and ambitions, the tree branches reach for the sun.