42 Myths and Legends of the Sea: Poems, Art Images, and Selected Verses

In the following section, different art images connected to legends and myths about the sea and its inhabitants are presented. Seas and oceans have captivated the imagination of artists, poets, novelists, and folklorists since time immemorial. Beliefs and superstitions of sailors were passed down through oral storytelling, ballads, and folktales that warned of the hidden dangers of the sea. Exploring unknown waters and continents sailors returned home with fascinating tales of the strange sea creatures that they encountered (Weiss and De Amicis, 2018). In his well-known book The sea: myths and legends, Angelo Rappoport (1928) explains that the entire compilation of Homer’s The Odyssey, is, in essence, a collection of sea stories. For the seaman, the sea is not an inanimate force but rather it is personified. It is “a living creature and is conscious of its existence” (p.10). Rappoport writes of the sea’s paradoxical states and moods. “The sea, that marvel of creation, immense and mysterious, silent or stormy, smooth or agitated, troubled and treacherous, has from time immemorial appealed to the imagination” of individuals (p. 15).

The sea is symbolically associated with divine inspiration, calm, purification, fertility, renewal/rebirth, and transformation. The sea “has powers to refresh, give perspective and take away the pressures of life. Its untiring motion is tied with our own daily rhythms, influenced by the moon and sun…the sea has much to say” (Richard Harrington, Life lessons from the ocean, 2020, p. 1). The following art images and poems/related text speak to the beauty, mystery, and power of the seas, oceans, lakes, and rivers. As you view the art images and read the corresponding text, what thoughts come to your mind about the sea and its importance? Fletcher Bassett (1892) writes that “the legendary lore of the sea is as diversified and interesting as the myths and traditions which haunt the imagination of landsmen, and it is not surprising that sailors, who observe the phenomena of nature under such varied and impressive aspects, should be found to cling with tenacious obstinacy to their superstitious fancies. The winds, clouds, waves, sun, moon, and stars have ever been invested with propitious or unlucky signs; and within a score of years we have met seamen who had perfect faith in the weatherlore and traditions acquired during their ocean wanderings” p. 11 ).

Further Reading

You can find The Sea: Myths and Legends by A.S. Rappoport here.

You can find Fletcher Bassett’s Sea Phantoms: Or, Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors in All Lands and at All Times here.

Robert Wilhelm Ekman (1808-1873). Ilmatar (1860). Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, Finland. Public Domain. Courtesy: By Robert Wilhelm Ekman – http://kokoelmat.fng.fi/app?si=A+II+1256, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66322449.Type your textbox content here.

Robert Wilhelm Ekman (1808-1873). Ilmatar (1860). Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, Finland. Public Domain. Courtesy: By Robert Wilhelm Ekman – http://kokoelmat.fng.fi/app?si=A+II+1256, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66322449.Type your textbox content here.

Ilmator (Luonnatar): Goddess of Creation

The Kalevala is Finland’s 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology. Angelo Rappoport describes the origins of Ilmator (Luonnotar) in his book The Sea: Myths and Legends:

The sea, according to many ancient traditions contained the germs of everything, and the earth, submerged in the sea, awaited the moment when the create fiat made it emerge above the waters. In the Kalevala the virgin Luonnatar (Ilmatar) came down from heaven and plunged into the sea, which made her fruitful. She swum in the waters for seven centuries, but one day she lifted her knee above the waters and the eagle deposited there his eggs. On the third day, Luonnotar (Ilmatar) having lowered her knew, the eggs fell into the sea. From their lower portion came the earth and from the upper portion the sublime heaven. The white of the eggs constituted the moon and the yolk the sun. (1928, p. 19)

Further Resources

Courtesy: Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1933. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/453683” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

Further Resources

“What a Tiny Masterpiece Reveals About Power and Beauty” by Jason Farago (The New York Times, 2021)

Excerpt from The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (Oxford, 1951)

Sadko and the Underwater Kingdom

Ilya Repin’s painting (above) beautifully illustrates the scene of Sadko and the sea nymphs (roussalki). Angelo S. Rappoport describes further in The Sea: Myths and Legends:

“Numerous stories of watermen and watermaids are told in Russian folklore, where the nyphs are known as the roussalki and the water-king as the Tsar Morskoi. The following story of a Novgorod trader names Sadko is a good specimen. One day, feelings rather dreary on account of his great poverty, he went down to the shore of the lake Leman and there began to play on his musical instrument, the gusli. Suddenly the waters of the lake were troubled and up rose the water-king, the Tsar Morskoi, who thanked the trader for his pleasant music and promised him a reward. Sadko thereupon threw a net into the lake a drew a great treasure.

He had now become a very wealthy merchant, and one day he was sailing over the blue sea when suddenly the vessel stopped and could proceed no farther. The sailors wondered on account of whose guilt their vessel had been stopped and decided to cast lots. The lot fell on Sadko, who now confessed that he had been sailing on the sea for twelve years, but had forgotten to pay tribute to the Tsar Morskoi or king of the waters. The sailors thereupon flung Sadko into the sea and the vessel could now move on. When Sadko sank to the bottom of the sea, he found a dwelling made of wood where lay the Tsar Morskoi.

‘I have been expecting thee for twelve years,” said the water-king, ‘and am anxious to hear thee play. Begin at once.’

Sadko obeyed and the water-king was greatly pleased with his music. The Tsar Morskoi was so pleased with Sadko that as a reward he offered him the hand of any of his thirty daughters. Sadko chose the nymph Volkhof and was married to her.” (pp. 190-191).

A Note About “A Mermaid” by John William Waterhouse (Royal Academy of Art)

“It is possible that Waterhouse’s painting of A Mermaid was inspired by Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Mermaid” (1830) which includes the lines

Who would be

A mermaid fair,

Singing alone,

Combing her hair

Tennyson’s poem goes on to describe the mermaid seeking and finding love among the mermen

Of the bold merry mermen under the sea.

They would sue me, and woo me, and flatter me,

In the purple twilights under the sea;

But the king of them all would carry me,

Woo me, and win me, and marry me.

However Waterhouse was also interested in the darker mythology of the mermaid as an enchantress. Mermaids traditionally were sirens who lured sailors to their death through their captivating song. They were also tragic figures as mermaids could not survive in the human world which they yearned for and men could not exist in their watery realm, so any relationship was doomed. In Waterhouse’s painting no sailors are depicted so that despite being a ‘siren’ the mermaid is shown as an alluring rather lonely figure, albeit with a fish tail. The atmosphere evoked is one of gentle melancholy as the mermaid sits alone in an isolated inlet, dreamily combing out her long hair with her lips parted in song. Beside her is a shell filled with pearls, which some believed to be formed from the tears of dead sailors.

When the work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1901 the Art Journal (p.182) noted her ‘wistful-sad look’ and the review remarked that ‘it tells of the human longings never to be satisfied … The chill of the sea lies ever on her heart; the endless murmur of the waters is a poor substitute for the sound of human voices; never can this beautiful creature, troubled with emotion, experience on the one hand unawakened repose, on the other the joys of womanhood’.”

Excerpt from “The Mermaid” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

I

Who would be

A mermaid fair,

Singing alone,

Combing her hair

Under the sea,

In a golden curl

With a comb of pearl,

On a throne?

II

I would be a mermaid fair;

I would sing to myself the whole of the day;

With a comb of pearl I would comb my hair;

And still as I comb’d I would sing and say,

‘Who is it loves me? who loves not me?’

I would comb my hair till my ringlets would fall

Low adown, low adown,

From under my starry sea-bud crown

Low adown and around,

And I should look like a fountain of gold

Springing alone

With a shrill inner sound

Over the throne

In the midst of the hall;

Till that great sea-snake under the sea

From his coiled sleeps in the central deeps

Would slowly trail himself sevenfold

Round the hall where I sate, and look in at the gate

With his large calm eyes for the love of me.

And all the mermen under the sea

Would feel their immortality

Die in their hearts for the love of me…..

“The Mermaid” can also be accessed in the early poems of Tennyson here.

The Nix, Nacken, or Nokken are a humanoid shapeshifting water spirits in Germanic mythology and folklore.

You can find more information about myths from the Norsemen here.

“To the Planet Venus” by William Wordsworth

Upon its approximation (as an Evening Star) to the Earth, January, 1838.

What strong allurement draws, what spirit guides,

Thee, Vesper! brightening still, as if the nearer

Thou com’st to man’s abode the spot grew dearer

Night after night? True is it Nature hides

Her treasures less and less. — Man now presides

In power, where once he trembled in his weakness;

Science advances with gigantic strides;

But are we aught enriched in love and meekness?

Aught dost thou see, bright Star! of pure and wise

More than in humbler times graced human story;

That makes our hearts more apt to sympathize

With heaven, our souls more fit for future glory,

When earth shall vanish from our closing eyes,

Ere we lie down in our last dormitory?

Courtesy: Gift of Mrs. Orme Wilson, in memory of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. J. Nelson Borland, 1959.“https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10534” is licensed under CC0 1.0.

A Note About John Singleton Copley (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“A prodigious talent at fifteen, John Singleton Copley learned his trade by copying reproductions of Italian mythological paintings. This charming juvenilia depicting Neptune and his retinue reminds us that Copley and the sitters in his later, mature portraits lived along the New England Coast and were deeply connected — economically and psychologically — to the sea.”

Excerpt from “A Hymn in Praise of Neptune” by Thomas Campion

Of Neptune’s empire let us sing.

At whose command the waves obey:

To whom the rivers tribute pay,

Down the high mountains sliding,

To whom the scaly nation yields

Wherein they dwell:

And ever sea-dog pays a gem

Yearly out of his war’ry cell

To deck great Neptune’s diadem

A Note About “The Mermaid of Zennor”

“The Mermaid of Zennor was Inspired by medieval legend of a mermaid who lived at Pendour Cove, near Zennor, Cornwall, about whom various stories are told. The young man in the picture is Matthew Trewhell, a chorister of St. Senara’s church in Zennor, with whose voice the mermaid was besotted. According to legend, he fell in love with the mermaid and went to share her watery home, although his voice can still be heard at Pendour Cove when he is singing.”

You can find “Ballad of the Mermaid of Zennor” by Vernon Watkins here.

You can find the complete illustrated version of Hindu Mythology by Alexander Donald MacKenzie here.

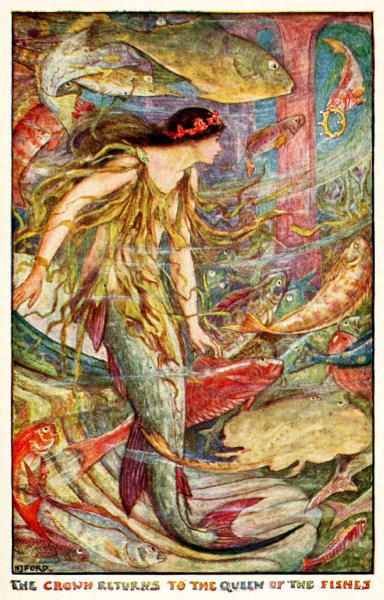

Courtesy: By Henry Justice Ford – Internet Archive identifier, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=109846904

Excerpt from “The Mermaid” by John Leyden

“Roused by that voice, of silver sound,

From the paved floor he lightly sprung,

And, glancing wild his eyes around,

Where the fair nymph her tresses wrung,

No form he saw of mortal mould;

It shone like ocean’s snowy foam;

Her ringlets waved in living gold,

Her mirror crystal, pearl her comb.

Her pearly comb the siren took,

And careless bound her tresses wild;

Still o’er the mirror stole her look,

As on the wondering youth she smiled.

Like music from the greenwood tree,

Again she raised the melting lay;

— “Fair warrior, wilt thou dwell with me,

And leave the Maid of Colonsay?

“Fair is the crystal hall for me,

With rubies and with emeralds set,

And sweet the music of the sea

Shall sing, when we for love are met.

“How sweet to dance, with gliding feet,

Along the level tide so green,

Responsive to the cadence sweet,

That breathes along the moonlight scene!

“And soft the music of the main

Rings from the motley tortoise-shell,

While moonbeams, o’er the watery plain,

Seem trembling in its fitful swell.

“How sweet, when billows heave their head,

And shake their snowy crests on high,

Serene in Ocean’s sapphire-bed,

Beneath the tumbling surge, to lie;

“To trace, with tranquil step, the deep,

Where pearly drops of frozen dew

In concave shells, unconscious, sleep,

Or shine with lustre, silvery blue!

“Then shall the summer …

Courtesy: By Arnold Böcklin – https://www.artsy.net/artwork/arnold-bocklin-meeresstille, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71047922

Excerpt from The Sea: Myths and Legends by Angelo S. Rappoport (1995/1928)

“Numerous tales connected with mermaids exist in the Shetland Islands. They are said to dwell in the sea among the fishes, in habitations of pearl and coral. They are resemble human beings but greatly exceed them in beauty. When they wish to visit the upper world they put on the garb of some fish, but woe to those who lose this garb, for then all their hopes of returning to the depths of the ocean are annihilated and they are obliged to stay where they are The sacred wells are a very favourite place with the fair children of the sea. Here, undisturbed by men, the green-haired beauties of the ocean lay aside their garb and revel in the clear moonlight. They are moral, and are often, on their excursions, exposed to dangers, for examples are not wanting of their having been taken by fishermen and killed. It often happens that earthly men get mermaids into their power an dmarry them” (p. 184).

Illustration by H. J. Ford for Andrew Lang’s The Orange Fairy Book:

You can find The Olive Fairy Book by Andrew Lang here.

“The Fisherman” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, translated by John Storer Cobb

The water rushed, the water swelled,

A fisherman sat by,

And gazed upon his dancing float

With tranquil-dreaming eye.

And as he sits, and as he looks,

The gurgling waves arise;

A maid, all bright with water drops,

Stands straight before his eyes.

She sang to him, she spake to him:

“My fish why dost thou snare,

With human wit and human guile,

Into the killing air?

Couldst see how happy fishes live

Under the stream so clear,

Thyself would plunge into the stream,

And live for ever there.

“Bathe not the lovely sun and moon

Within the cool, deep sea,

And with wave-breathing faces rise

In twofold witchery?

Lure not the misty heaven-deeps,

So beautiful and blue?

Lures not thine image, mirrored in

The Fresh eternal dew?

The water rushed, the water swelled,

It clasped his feet, I wis’

A thrill went through his yearning heart,

As when two lovers kiss!

She spake to him, she sang to him:

Resistless was her strain;

Half drew him in, half lured him in;

He ne’er was seen again.

“The Fisherman” is a poem written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1799. In the poem the mermaid enchants the fisherman and lures him to the depths of the ocean. John Storer Cobb’s English translation of “The Fisherman” was first published in Goethe: Poetical Works, vol. 1 (Francis A Niccolls & Company, 1902).

A Note About “Allegory: The Ship of State” (National Maritime Museum)

“An allegorical painting, which alludes to the political disaffection between the Low Countries and Spain, and the Protestant revolt against the Roman Catholic Church, the state church of Spain; thus the ship can be equated with the Catholic Church, under Phillip II. The ship, on a green sea, steers its way through small islands of barren rock, where dangers threaten. To the right background is an island with a cave, wherein wolves lurk. In front to the right, a volcano spews out flames and rocks. The rock in the right foreground appears to be hit by a meteorite. In the centre foreground two mermaids (symbols of lasciviousness) with looking glasses are arranged, holding combs in their hands and resting on a rock. To the left is another rock and behind a giant, waist high, in the water. He brandishes a club with his right hand in the direction of the ship. In the left distance, two giants stand on another rock and they also brandish clubs. These represent the dangers to which the ship will succumb if she founders.”

Bon

“Annabel Lee” by Edgar Allan Poe

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love—

I and my Annabel Lee—

With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in Heaven,

Went envying her and me—

Yes!—that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)}

That the wind came out of the cloud by night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

Teaching and Learning Resources for Edgar Allan Poe

The Bells and Other Poems by Edgar Allan Poe

Education and Other Programs, The Poe Musem

Collated works by Edgar Allen Poe (Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore)

“The City in the Sea” by Edgar Allan Poe

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.

There shrines and palaces and towers

(Time-eaten towers that tremble not!)

Resemble nothing that is ours.

Around, by lifting winds forgot,

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

No rays from the holy heaven come down

On the long night-time of that town;

But light from out the lurid sea

Streams up the turrets silently—

Gleams up the pinnacles far and free—

Up domes—up spires—up kingly halls—

Up fanes—up Babylon-like walls—

Up shadowy long-forgotten bowers

Of sculptured ivy and stone flowers—

Up many and many a marvellous shrine

Whose wreathèd friezes intertwine

The viol, the violet, and the vine.

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

So blend the turrets and shadows there

That all seem pendulous in air,

While from a proud tower in the town

Death looks gigantically down.

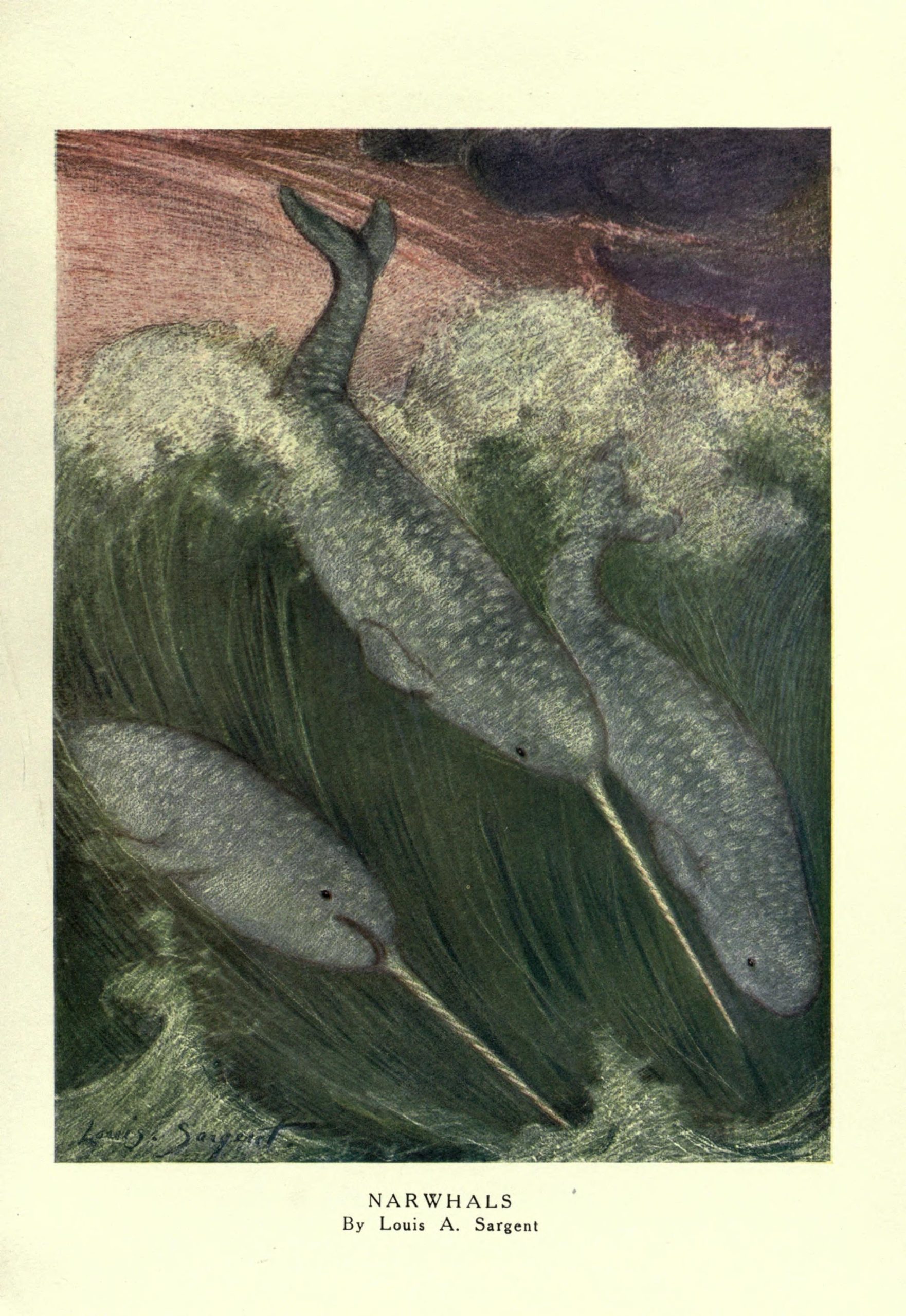

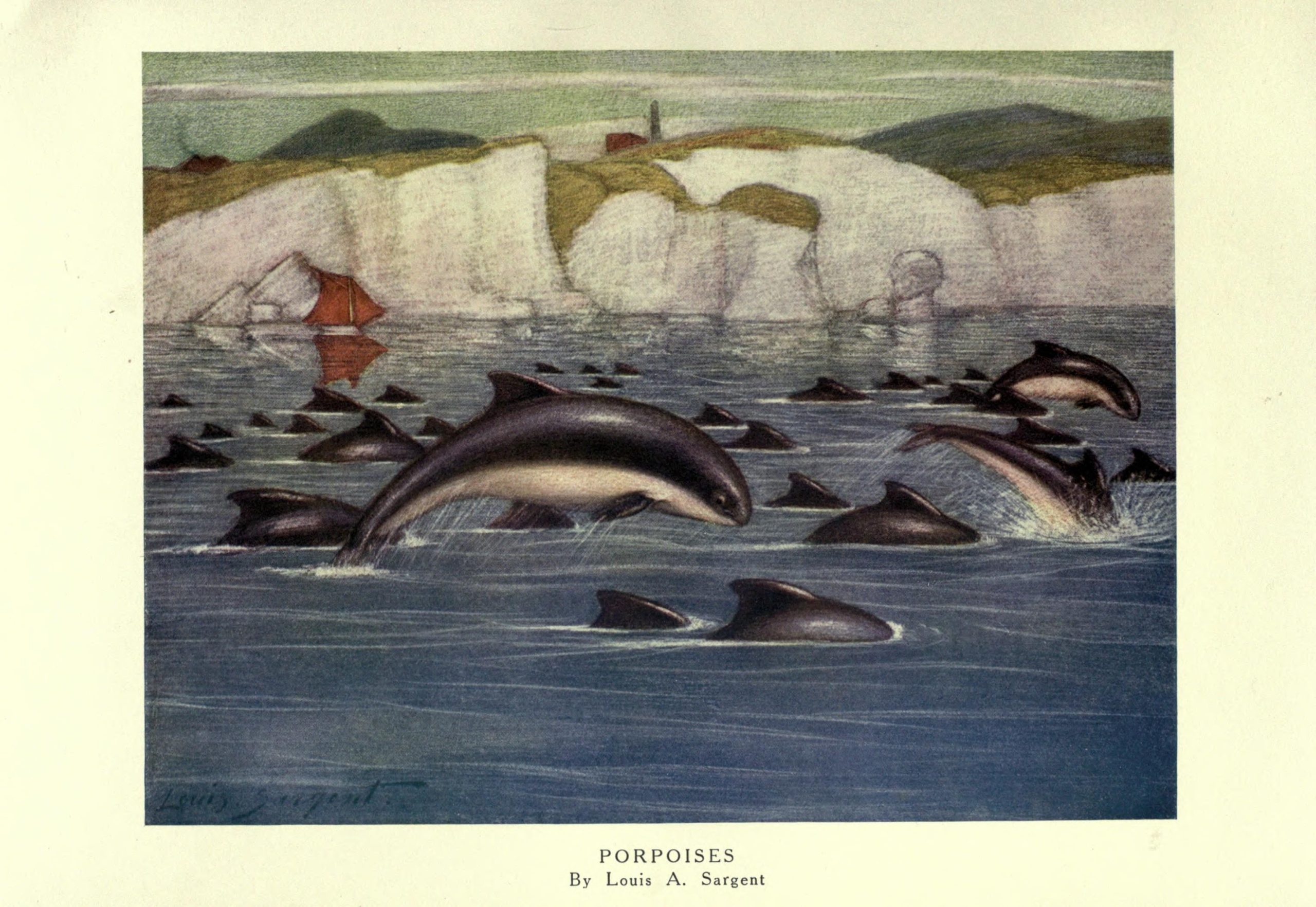

Courtesy: By Finn, Frank – https://www.flickr.com/photos/biodivlibrary/8116047765, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43410733

Excerpt from The Sea Around Us by Rachel Carson (Oxford, 1951)

“The existence of abundant deep-sea fauna was discovered probably millions of years ago, by certain whales and also, it now appears, by seals. The ancestors of all whales, we know by fossil remains, were land mammals. They must have been predatory beasts, if we are to judge by their powerful jaws and teeth. Perhaps in their foragings about the deltas of great rivers or around the edges of shallow seas, they discovered the abundance of fish and other marine life and over the centuries formed the habit of following them farther and farther into the sea. Little by little their bodies took on the form more suitable for aquatic life” (p. 45).

Excerpt from The Science of Hope: Eye to Eye with our World’s Wildlife by Dr. Weibke Finkler and Scott Davis (Exisle Publishing, 2021)

“Whales are the mega into charismatic megafauna. They are the largest living things that have ever existed upon Earth. Yet not too long ago we hunted them to near extinction. Now, however, we are at risk of loving them to death.

We are intrigued by whales; they are mammals like us, yet they appear otherworldly, floating through the oceans like gargantuan submarines. There are two basic types: toothed whales and baleen hales. Most of the world’s 90 different whale species are toothed whales, including one of the most charismatic of tall, the Killer Whale or Orca, which, in fact, is the largest member of the dolphin family. They have teeth and hunt their prey using echolocation … Baleen whales, by comparison, do not use echolocation and feed instead by using baleen, skin-like plates that hang down from their upper jaw and are used to filter their prey form the seawater” (p. 14).

“Whale watching can have serious negative impacts on populations of whales due to proximity and the speed of boats, boat crowding underwater noise pollution and disturbance of their most important behaviors such as sleeping, feeding, resting, and nursing their young. Yet responsible whale watching which should occur at an approximately respectful distance from the whales, has the potential to benefit whale and the ecology of the oceans themselves by raising environmental awareness and inducing pro-environmental behavioral change in us (see references for organizations that work to save the whales)” (pp. 16 -19).

Courtesy: By Finn, Frank – https://www.flickr.com/photos/biodivlibrary/8116046227, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43410782

Further Resources

You can find more works by Louis Augustus Sargent here.

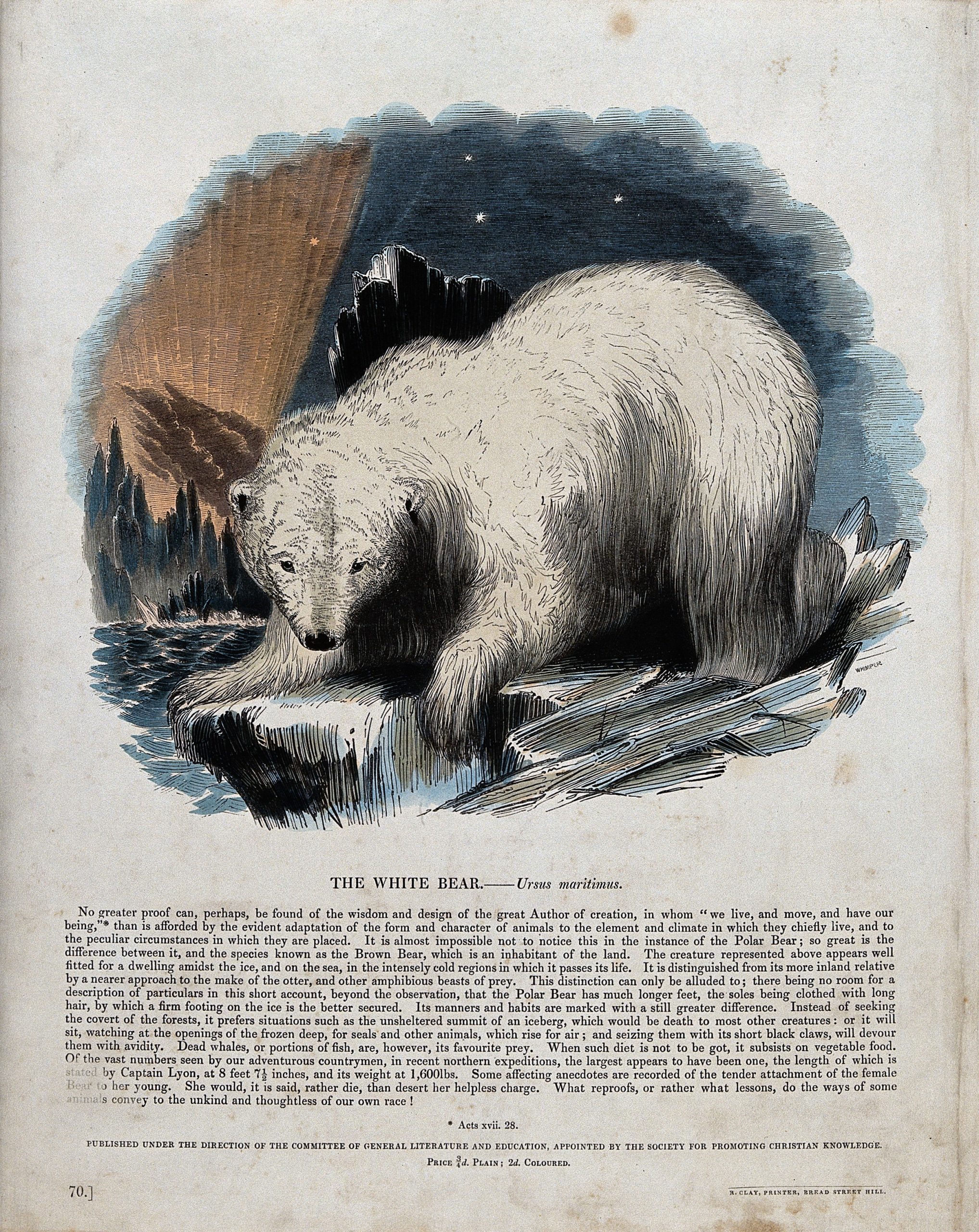

“Arctic Science Series: Passion for the Polar Bear” by Robert Letcher (Government of Canada)

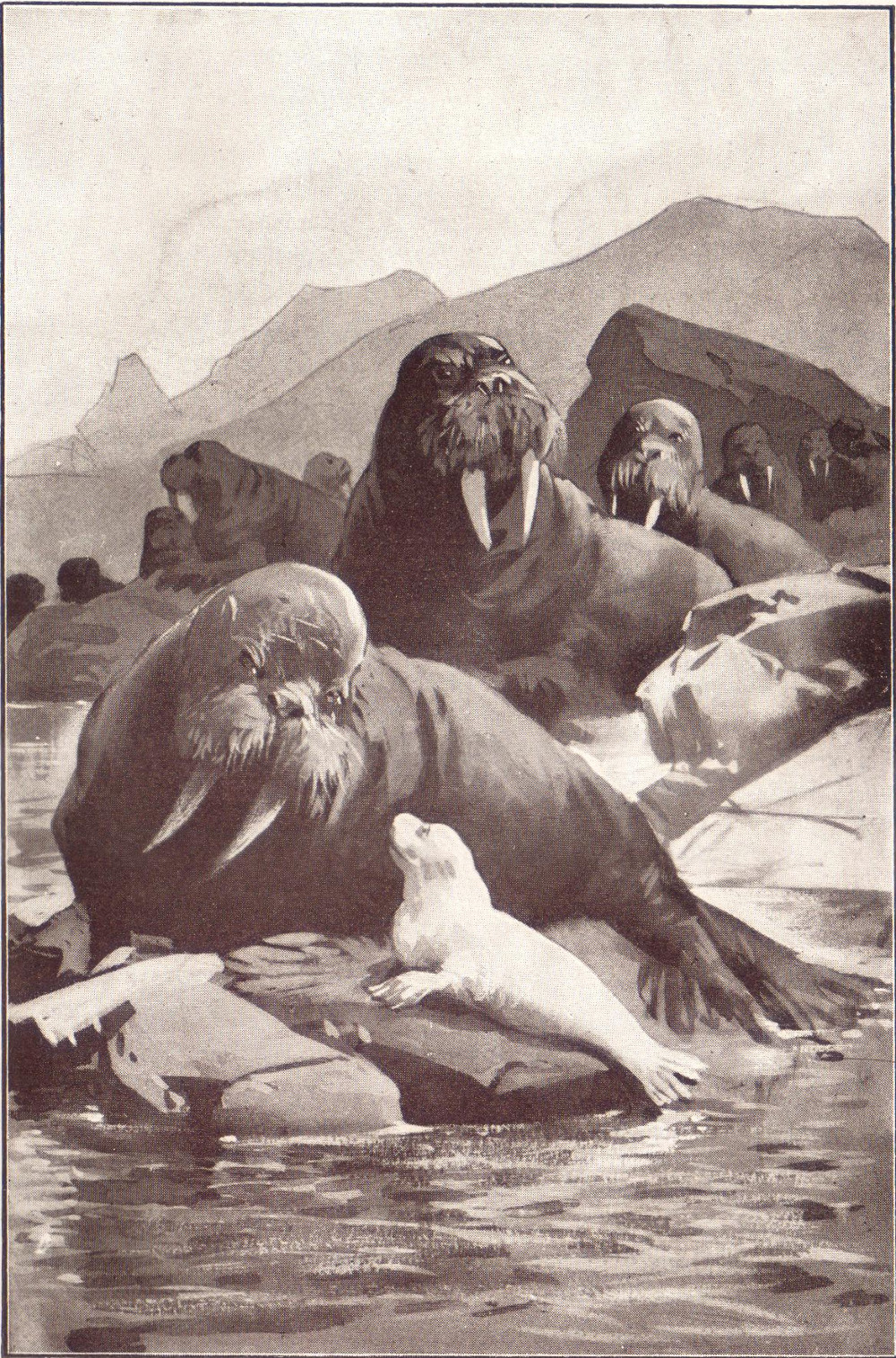

“The Walrus lives near relatively shallow water where it spends much of its time looking for benthic bivalve mollusks, its preferred diet. The Walrus is a social animal and spends much of its time on sea ice. As sea ice thins and retreats farther north, walrus, which rely on sea ice to rest on between foraging bouts, and polar bears, which need sea ice to hunt seals, will either be displaced from essential feeding areas or forced to expend additional energy swimming to land-based haul-outs.”

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3379351

Courtesy: By Unknown author – “Geist und Galanterie”. Catalogue of a exhibition, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn 2002/2003, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3246083

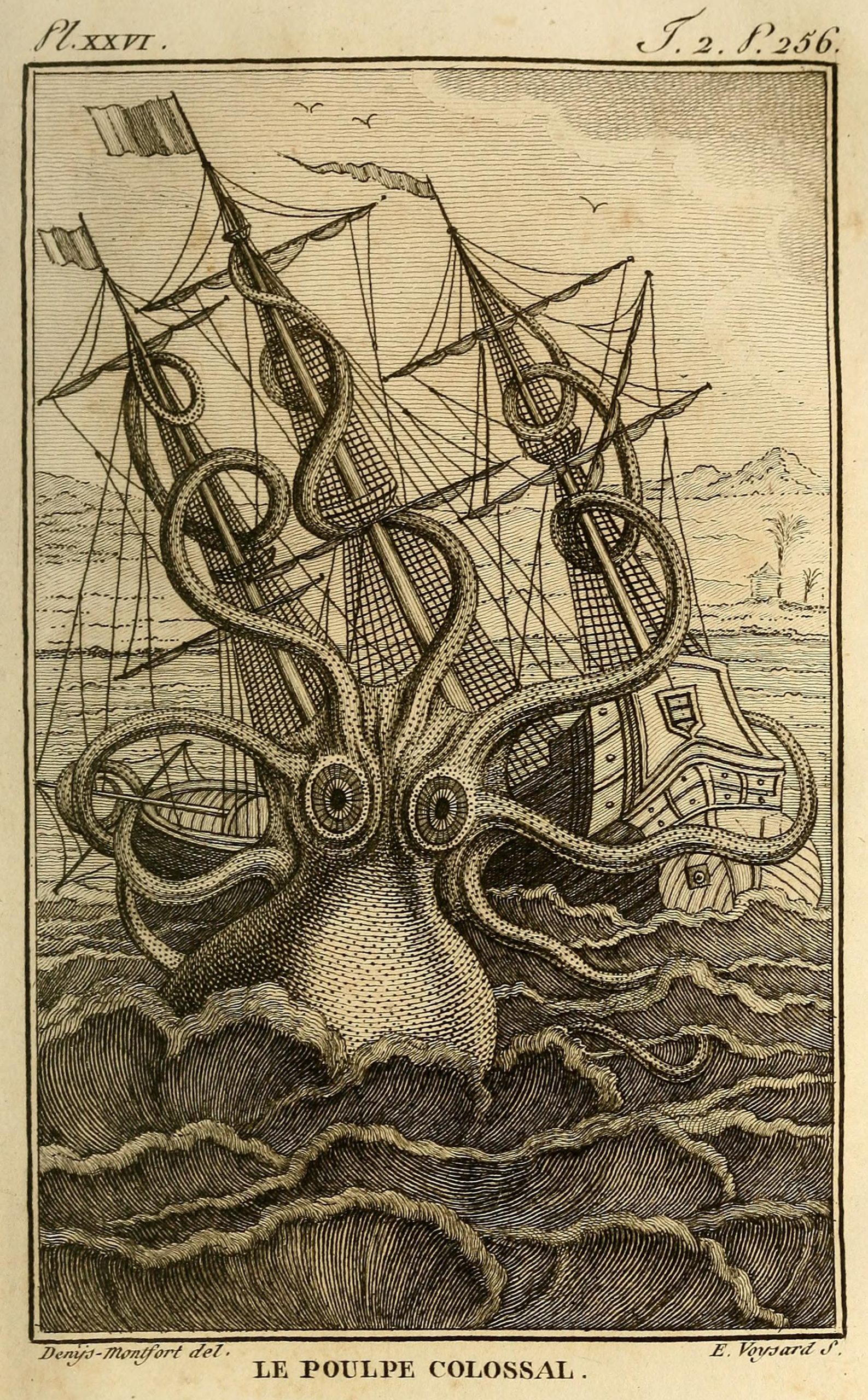

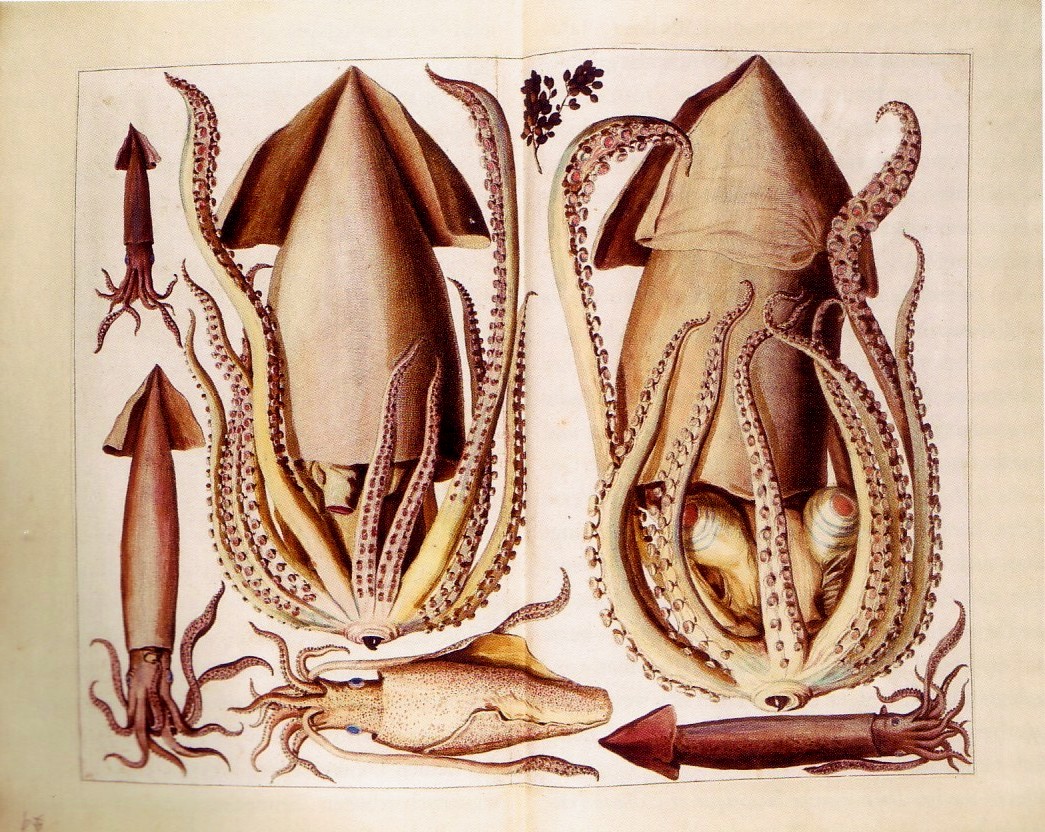

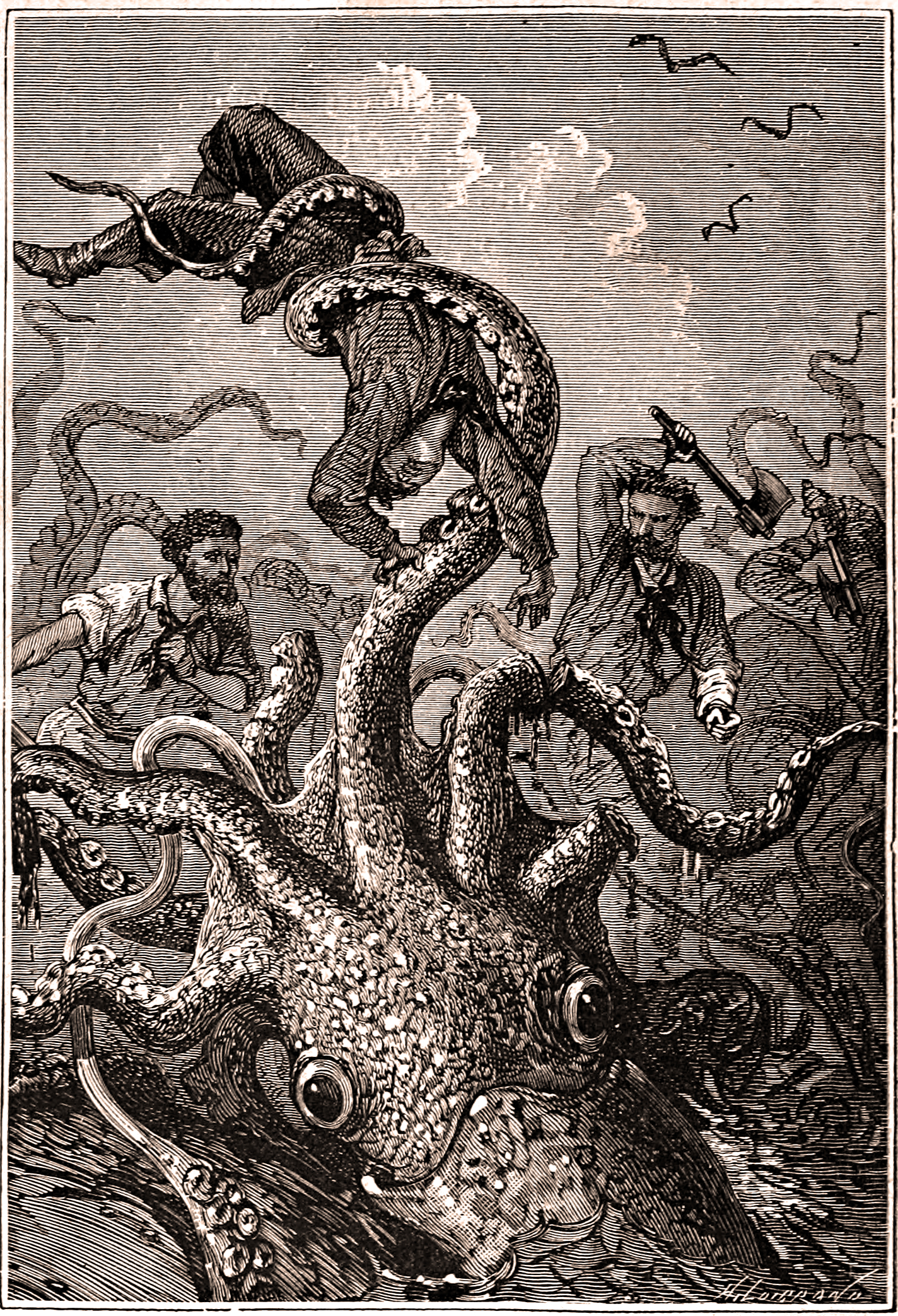

Illustrations from Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea is an adventure and fantasy/science fiction sea novel by the French writer Jules Verne. It was first published in French as Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers in 1869–70. It is perhaps the most popular book of his science-fiction series Voyages Extraordinaires (1863–1910). With new technologies and an increasing interest in deep sea exploration, science fiction and fantasy novels become very popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many contemporary twenty-first-century sea fantasy novels draw upon the imaginative worlds created by writers like Jules Verne. The realistic novels of Joseph Conrad also became very popular in the twentieth century. Heart of Darkness (1899), Lord Jim (1900), and the short story “The Secret Sharer” (1909) are among some of Conrad’s most enduring works.

Excerpts from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne

“The year 1866 was signalised by a remarkable and mysterious and puzzling phenomenon, which doubtless no one has yet forgotten. Not to mention rumours which agitated the maritime population and excited the public mind, even in the interior of continents, seafaring men were particularly excited. Merchants, common sailors, captains of vessels, skippers, both of Europe and America, naval officers of all countries, and the Governments of several states on the two continents, were deeply interested in the matter.

For some time past, vessels had been met by ‘an enormous thing,’ a long object, spindle-shaped, occasionally phosphorescent, and infinitely larger and more rapid in its movements than a whale.

The facts relating to this apparition (entered in various log-books) agreed in most respects as to the shape of the object or creature in question, the untiring rapidity of its movements, its surprising power of locomotion, and the peculiar life with which it seemed endowed. If it was a cetacean, it surpassed in size all those hitherto classified in science. Taking into consideration the mean of observations made at divers times,—rejecting the timid estimate of those who assigned to this object a length of two hundred feet, equally with the exaggerated opinions which set it down as a mile in width and three in length,—we might fairly conclude that this mysterious being surpassed greatly all dimensions admitted by the ichthyologists of the day, if it existed at all. And that it did exist was an undeniable fact; and, with that tendency which disposes the human mind in favour of the marvellous, we can understand the excitement produced in the entire world by this supernatural apparition. As to classing it in the list of fables, the idea was out of the question…”

“The sea has its large rivers like the continents. They are special currents known by their temperature and their colour. The most remarkable of these is known by the name of the Gulf Stream. Science has decided on the globe the direction of five principal currents: one in the North Atlantic, a second in the South, a third in the North Pacific, a fourth in the South, and a fifth in the Southern Indian Ocean. It is even probable that a sixth current existed at one time or another in the Northern Indian Ocean, when the Caspian and Aral Seas formed but one vast sheet of water…”

Further Resources

“Minoan Art – The Most Notable Minoan Artifacts, Paintings, and Art” by Isabella Meyer (Art in Context, 2023)