13 Out of Fire: Dragons East and West

Out of Fire: Dragons East and West

Thomas Cooper Gotch (1854-1931). Innocence, 1904. Falmouth Art Gallery, Falmouth, England. Art Daily. Public Domain.

By Thomas Cooper Gotch – Artdaily.com, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12134307

Dragons in Myths, Folktales, and Legends

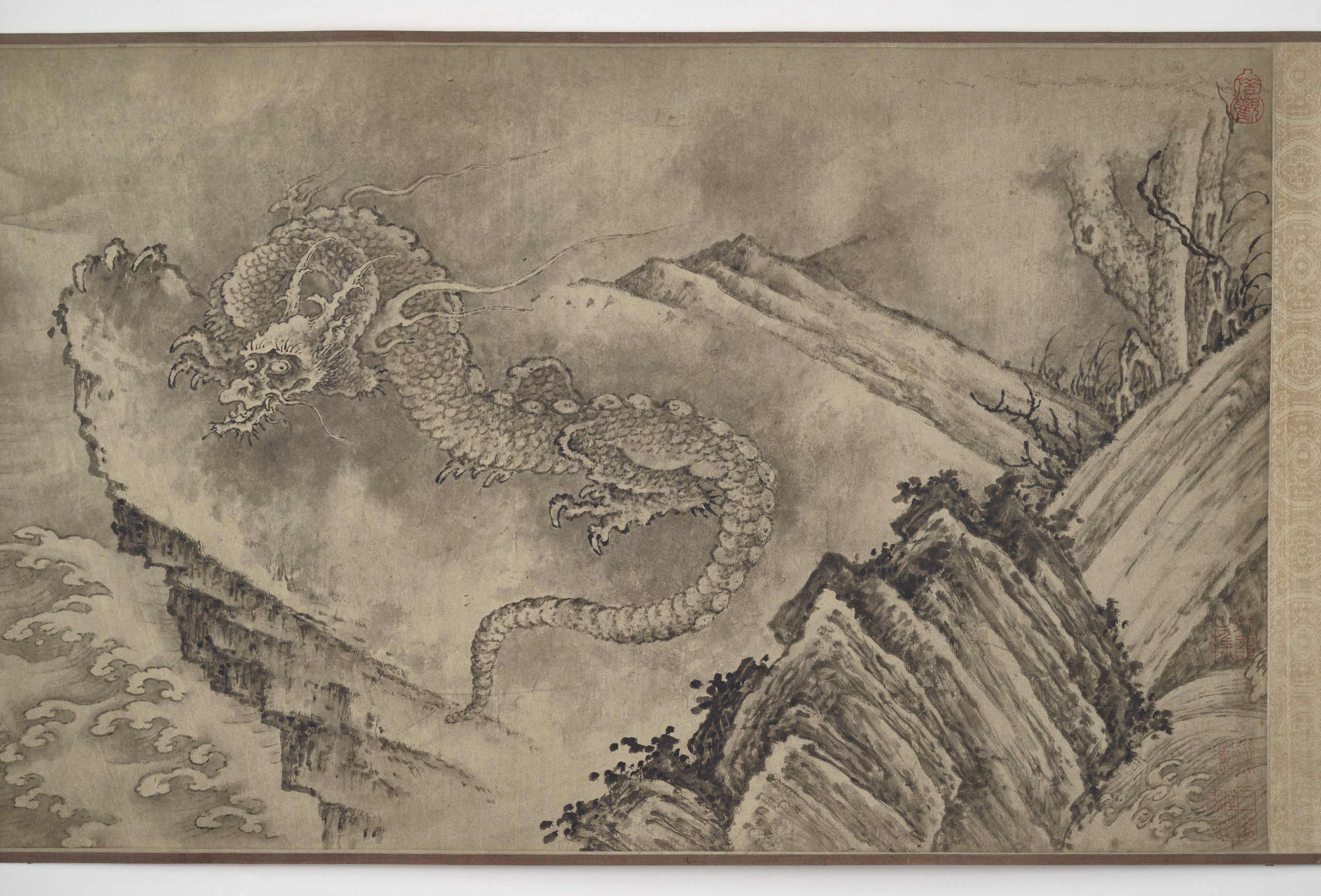

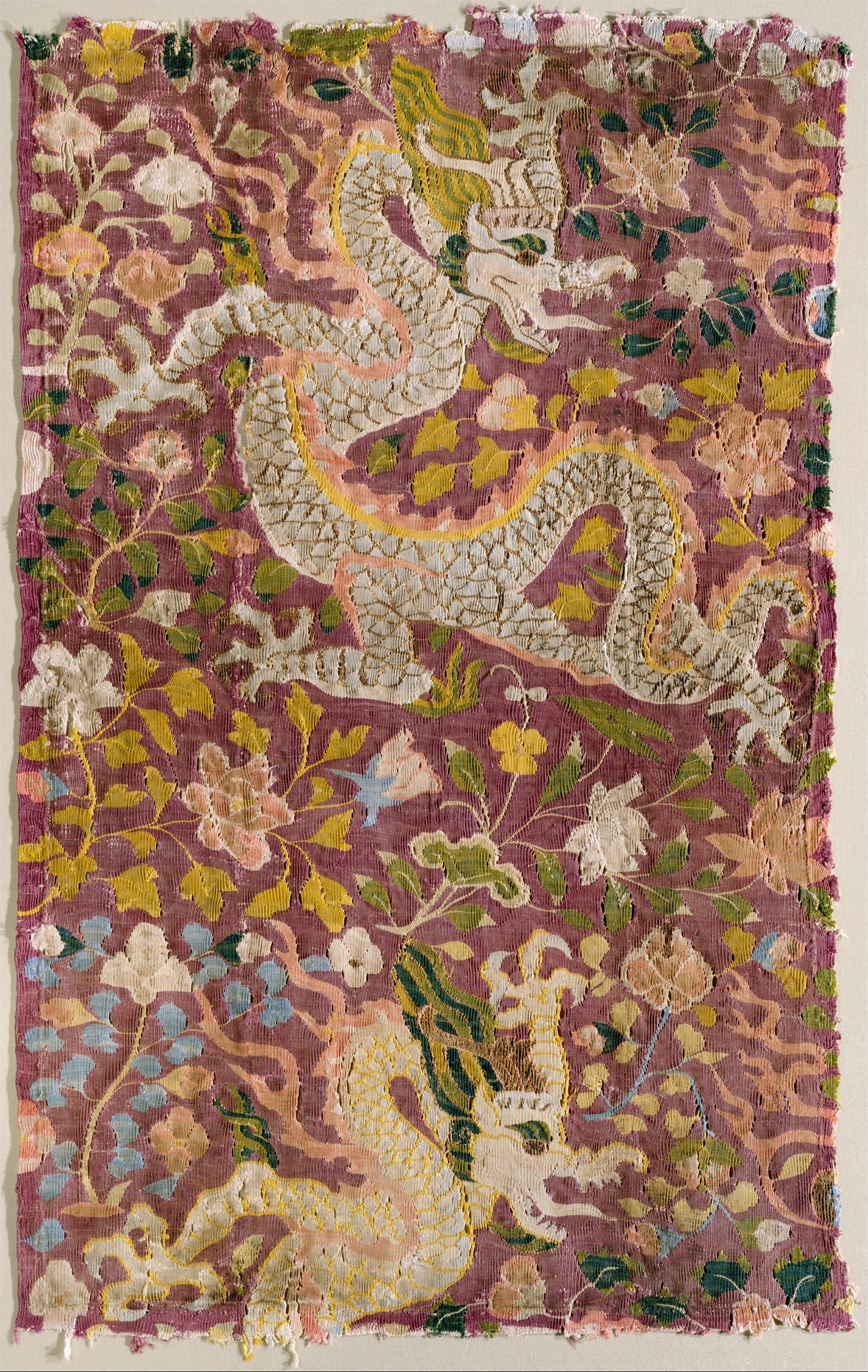

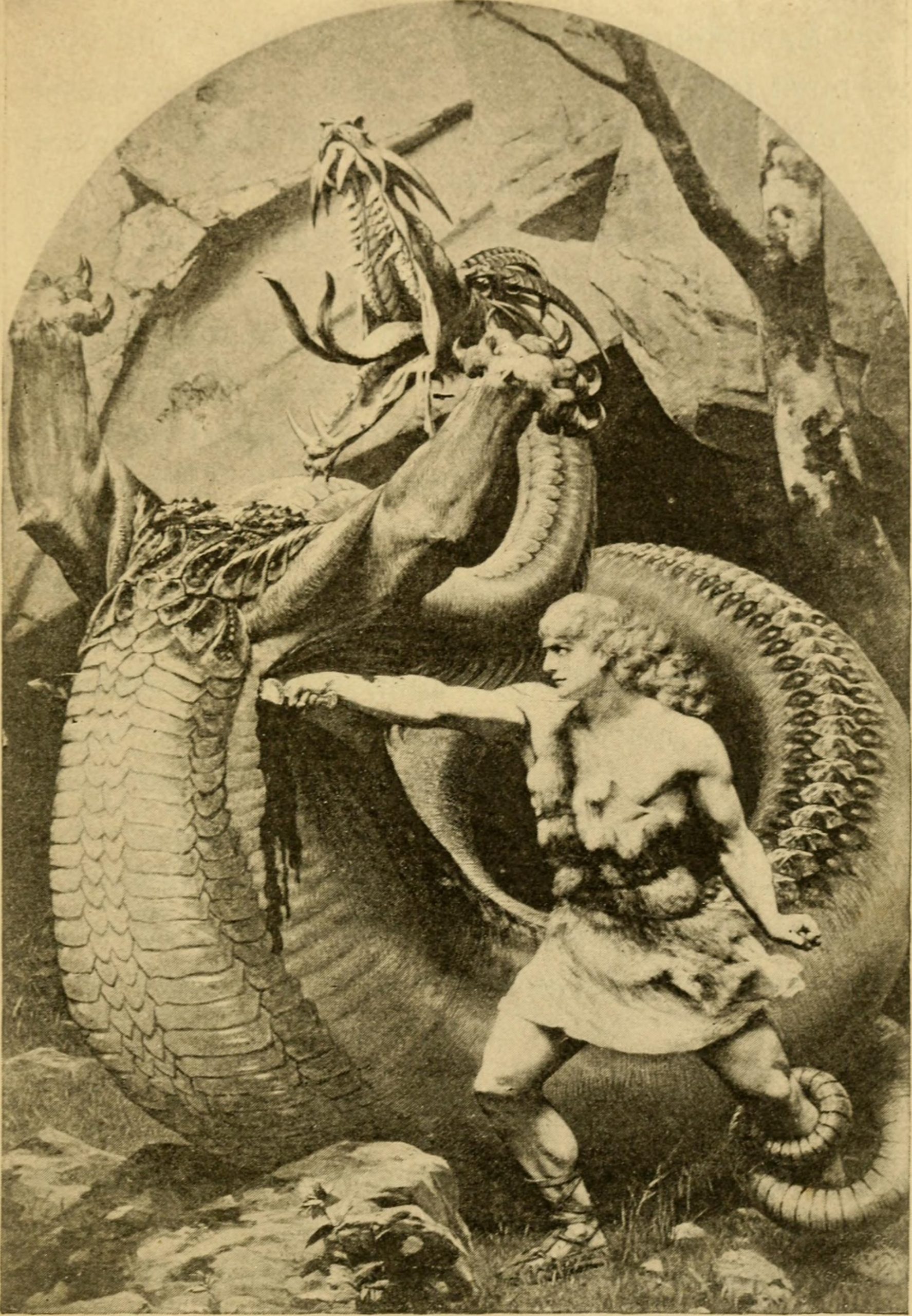

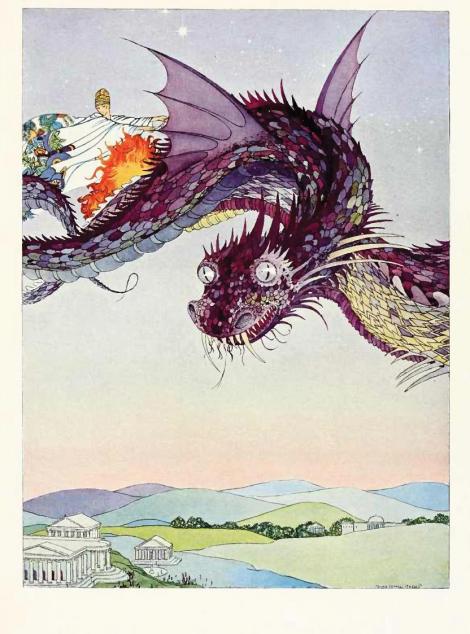

The word Dragon has ancient Greek Origins in the word “drakonta” or “to watch” (Rosen, 2009). Throughout many world cultures, dragons have been a central feature in myths, folktales, and legends. They are presented as fabulous animal/monster that integrate numerous animal features with fantastical faces and animal hybrid parts. In some cultures, the dragon was symbolic of danger and evil. The legendary Phoenician hero Cadmus was famous for his skill in defeating monsters and dragons. Persian folktales depict dragons as fire breathing man eaters. He was the first Greek hero and, alongside Perseus and Bellerophon, the greatest hero and slayer of monsters before the days of Heracles. Heroes gain acclaim if they are able to a slay a dragon that has been threatening the people of a town. In ancient Babylonian folklore, the principal god created the world by killing the female dragon Tiamat. Rosen (2009) describes the famous story of St. George, the patron saint of England (280-303 CE) and his encounter with the dragon that had been killing the people of a town. The legend of St. George influenced many Celtic and Norse/Germanic folk tales of dragons. By contrast, in many Asian cultures, the dragon is a benevolent and powerful symbol of protection, good fortune, regeneration, and authority. The strengths and magical powers of dragons are connected with the powers of the land, air, and sea. In China, dragons were colour coded to reflect their special realm. Blue dragons were thought to symbolize the east and are a sign that spring is soon arriving. The heaven dragon “Tianlong” is the celestial dragon that pulls the chariots of the gods in the cosmos. Dilong is the earth dragon who controls the rivers; while in the spring Dilong resides in the heavens, in the autumn, it lives in the sea. The winged dragon Yinglong is the powerful dragon that served and protected the emperor (Rosen,2009, p. 63). Kendall, Norell, and Ellis (2016) explain that dragons were central to traditional Chinese cosmology and folklore that was passed down orally and in writing throughout the generations. “Chinese civilizations depended on the productivity of farmers who relied on seasonal rain. On the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, the dragon king would rise to the heaven from his watery palace and release the timely rain” (p. xi). Fate, health, and prosperity were interconnected to the mythic world of dragons. Dragons have existed in mythologies and ancient cultures for thousands of years. Humans have projected qualities such as intelligence, danger, mysterious, and power to them. For many Asian cultures dragons remain a protective force representing wisdom, intelligence, and power.

Poems about Dragons.

https://aestheticpoems.com/dragon-poems/

https://exhibitions.bristolmuseums.org.uk/japanese-prints/hokusai-hiroshige-landscapes/

Learning as a lifelong journey:

“Since the age of six, I have had a passion for drawing things. Now that I am 75 years, I have finally learned something of the true quality of birds, animals, insects, fishes, and of the vital nature of grasses and trees. By the time I am 89, I shall have made more progress. By the time I am 90, I shall understand the deeper meaning of things. When I am 100, I shall be truly marvelous; and at 110 each dot and each line https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hokusaiwill possess a life of its own.”– Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾 北斎, c. 31 October 1760 – 10 May 1849) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hokusai

Dragons as Symbols of Strength and Wisdom

In East Asian culture, the legendary dragon is a powerful symbol of strength, wisdom, protection and fortune. Ancient myths and folklore feature dragons as other worldly being that are interconnected with the lives of humans. The dragon motif/symbol/herald was associated with imperial power and brilliant robes, pottery, scrolls, and other artefacts featured a wide array of sea and air dragons. The sea, wind, rainfall, vegetation, and heavenly powers were connected with dragons. The visual images of dragons have their origins in real-life reptilian animals. In comparison to the depiction of dragons in Western culture, where they are seen as evil creatures, East Asian dragons have been used to ward off evil spirits, protect the innocent and provide safety and security to those who possess it.

Wikimedia Commons.

For more information about the great Japanese artist Hokusai, pleaese open the link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hokusai

“Hokusai Says

Look Carefully

He says pay attention, notice.

He says keep looking, stay curious.

He says that there is no end to seeing.”

Retrieved October 13, 2022

Famous Poems about Dragons

https://www.poetrysoup.com/famous/poems/dragons

The Joy of Little Things by Robert Service (1874-1958)

It’s good the great green earth to roam,

Where sights of awe the soul inspire;

But oh, it’s best, the coming home,

The crackle of one’s own hearth-fire!

You’ve hob-nobbed with the solemn Past;

You’ve seen the pageantry of kings;

Yet oh, how sweet to gain at last

The peace and rest of Little Things!

Perhaps you’re counted with the Great;

You strain and strive with mighty men;

Your hand is on the helm of State;

Colossus-like you stride . . . and then

There comes a pause, a shining hour,

A dog that leaps, a hand that clings:

O Titan, turn from pomp and power;

Give all your heart to Little Things.

Go couch you childwise in the grass,

Believing it’s some jungle strange,

Where mighty monsters peer and pass,

Where beetles roam and spiders range.

‘Mid gloom and gleam of leaf and blade,

What dragons rasp their painted wings!

O magic world of shine and shade!

O beauty land of Little Things!

I sometimes wonder, after all,

Amid this tangled web of fate,

If what is great may not be small,

And what is small may not be great.

So wondering I go my way,

Yet in my heart contentment sings . . .

O may I ever see, I pray,

God’s grace and love in Little Things.

So give to me, I only beg,

A little roof to call my own,

A little cider in the keg,

A little meat upon the bone;

A little garden by the sea,

A little boat that dips and swings . . .

Take wealth, take fame, but leave to me,

O Lord of Life, just Little Things.

https://allpoetry.com/The-Joy-Of-Little-Things

For more information about the British-Canadian poet Robert Service, please open the link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_W._Service

Who Has Seen the Wind?

BY CHRISTINA ROSSETTI (1830-1894)

Who has seen the wind?

Neither I nor you:

But when the leaves hang trembling,

The wind is passing through.

Who has seen the wind?

Neither you nor I:

But when the trees bow down their heads,

The wind is passing by.

Retrieved November 30, 2022 All Poetry Web Page https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43197/who-has-seen-the-wind

This Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) art work is more than sixteen feet long. “It vividly portrays eleven dragons. They are dancing on high cliffs, whirling through dense clouds, and dashing in and out of waves. As they roll their eyes, flex their claws, and open their mouths to roar, the whole universe seems to be instilled with their immense powers. The dragons are depicted as a combination of the horns of a deer, head of an ox, eyes of a ghost, mouth of a donkey, beard of a catfish, mane of a lion, scales of a carp, claws of an eagle, and body of a serpent” (Smithsonian Art Museum, Asian Gallery, Notes. Retrieved September 22, 2022)

Teaching Resources on Asian Art: Smithsonian Museum of Art. Washington, DC.

https://asia.si.edu/learn/for-educators/

“None of the animals is so wise as the dragon. His blessing power is not a false one. He can be smaller than small, bigger than big, higher than high, and lower than low.”

–-Chinese scholar Lu Dian (AD 1042-1102)

Symbolism of Dragons (Ronneberg & Martin, 2021)

“Long ago, the dragon began as a winged or flying serpent, expressing the primal harmony between the subterranean and aerial dimensions. This fabulous creatures is chthonic, darkly reptilian and birdlike, lofty and expansive. As an image of the unconscious, the dragon moves in and out of the psyche’s darkness, showing only parts of itself, evanescent. One of the aspects is the “beneficial” demon that causes the rising of life-giving nourishment from the vegetative realms and contains in its had the secret of regeneration. The Greek drakon signifies aliveness, gleaming light, and the eye that flashes fire and sees keenly, like the generative ‘eye’ of the unconscious. One of alchemy’s oldest emblems is the dragon” (Ronneberg & Martion, 2021, p. 704).

Source: Ronneberg, & Martin, . The book of symbols: Reflections on archetypcal images. Tashcen.

Chinese Poetry Resource

Project Gutenberg's A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems, by Various Poets

translated by Arthur Waley,London: Constable & Company Ltd., 1918).

CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD.

Produced by Henry Flower and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)Type your textbox content here.

Dragons: Emissaries linking heaving and earth

“The dragons of East Asian legend have sweeping powers. They breathe clouds, move the seasons, and control the waters of rivers, lakes, and seas. They are linked with yang, the masculine principle of heat, light, and action, and opposed to yin, the feminine principle of coolness, darkness, and repose. Dragons have been part of East Asian culture for more than 4,000 years. In the religious traditions of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, they have been honored as sources of power and bringers of rain.” Retrieved November 30, 2022 American Museum of Natural History, New York City. https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/mythic-creatures/dragons/asian-dragons

“The Narrow Road to the Deep North” by Basho

Teaching and Learning Resources:

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/here-be-medieval-dragons/

https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/lesson-plans/medieval-beasts-and-bestiaries

Wyvern

The Wyvern is a two-footed dragon with wings. It can have the body of a swan (e.g. the Leicester Wyvern) or other bird/animal. It is rarely described as fire-breathing.

“The wyvern in its various forms is important in heraldry, frequently appearing as a mascot of schools and athletic teams (chiefly in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada). It is a popular creature in European literature, mythology, and folklore. Today they are often used in fantasy literature and video games. The wyvern in heraldry and folklore is rarely fire-breathing, unlike four-legged dragons.” November 29, 2022 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyvern

Heraldry in Art

https://www.pinterest.it/zdirad/heraldry-in-the-metropolitan-museum-of-art/

Peaceful Animals

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/into-the-wild-peaceful-animal-paintings/

Hans Hoffman and other Artists Specializing in Animal Paintings

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/animals-created-by-hans-hoffmann/

Northern Germany, Medieval Aquamanile (drinking vessel) in the Form of a Dragon, 1200. The Cloisters Medieval Art Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/471287” by Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 by 1.0.Metropolitan Museum of Art Note about the Dragon Vessel

Northern Germany, Medieval Aquamanile (drinking vessel) in the Form of a Dragon, 1200. The Cloisters Medieval Art Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. “https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/471287” by Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 by 1.0.Metropolitan Museum of Art Note about the Dragon Vessel

“This striking vessel represents a dragon, which is supported by its legs in front and on the tips of its wings behind, with a tail that curls up into a handle. It was filled through an opening in the tail, now missing its hinged cover. Water was poured out through the spout formed by the hooded or cowled figure held between the dragon’s teeth. In addition to its visual power, this aquamanile is distinguished by fine casting, visible in the carefully chased dragon’s scales and other surface details” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Notes. Retrieved October 10, 2022 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/471287)

Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, 1947.

“Many, many,

things come to mind

cherry blossoms.” -Basho

Internet Archive: Audio Readings of poetry by Basho. https://archive.org/details/basho_the_chief_poet_of_japan_1502_librivox

“In the upper right, the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, is seated in meditation for such a long time that birds have begun assembling twigs for a nest atop his head. In the scroll’s lower part are Buddhist disciples grouped around a dragon. Dragons have been part of Buddhist culture since antiquity; in Chinese Buddhism the dragon is often interpreted as a symbol of enlightenment.” (Cleveland Museum of Art). J. H. Wade Fund.

For more information about Japanese Folk and Fairy Tales.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4018/4018-h/4018-h.htm

Green Willow and other Japanese Tales (by James Grace and Illustrated by Warwick Goble). McMillan & Co. 1910.

Internet Archive eBook: https://archive.org/details/greenwillowother00jame/page/n7/mode/2up (Courtesy: New York Public Library).

Classical Japanese Poetry: Internet Archive eBook (edited by Basil Hall Chamberlain, 1850-1935), 1880. Trubner & Co.

https://ia800908.us.archive.org/26/items/classicalpoetry01chamgoog/classicalpoetry01chamgoog.pdf (Courtesy: University of Michigan).

To learn more about Basil Hall Chamberlain (British Academic and Japonologist) please open the link below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basil_Hall_Chamberlain

Asian Art Archives (collected articles): Daily Art Magazine

https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/category/regions/asian-art/

Tomonori Kino

Excerpt from A Hundred Verses from Old Japan (The Hyakunin-isshu) translated by William N. Porter, 1909.The Fall of Cherry Blossoms by Tomimoro Kino

Hikari nodokeki

Haru no hi ni

Shizu kokoro, naku

Hana no chiruramu.

THE spring has come, and once again

The sun shines in the sky;

So gently smile the heavens, that

It almost makes me cry,

When blossoms droop and die.

(Retrieved August 2, 2023 https://sacred-texts.com/shi/hvj/).

Note: “This is a collection of 100 specimens of Japanese Tanka poetry collected in the 13th Century C.E., with some of the poems dating back to the 7th Centry. Tanka is a 31 syllable format in the pattern 5-7-5-7-7. Most of these poems were written about the time of the Norman Conquest and display a sophistication that western literature would not achieve for a long time thereafter. These little gems are on themes such as nature, the round of the seasons, the impermanence of life, and the vicissitudes of love. There are obvious Buddhist and Shinto influences throughout. Porter’s notes put the poems into a cultural and historical context” ( Porter, W. 1909, Sacred Texts, Japanese Verse 3 https://sacred-texts.com/shi/)

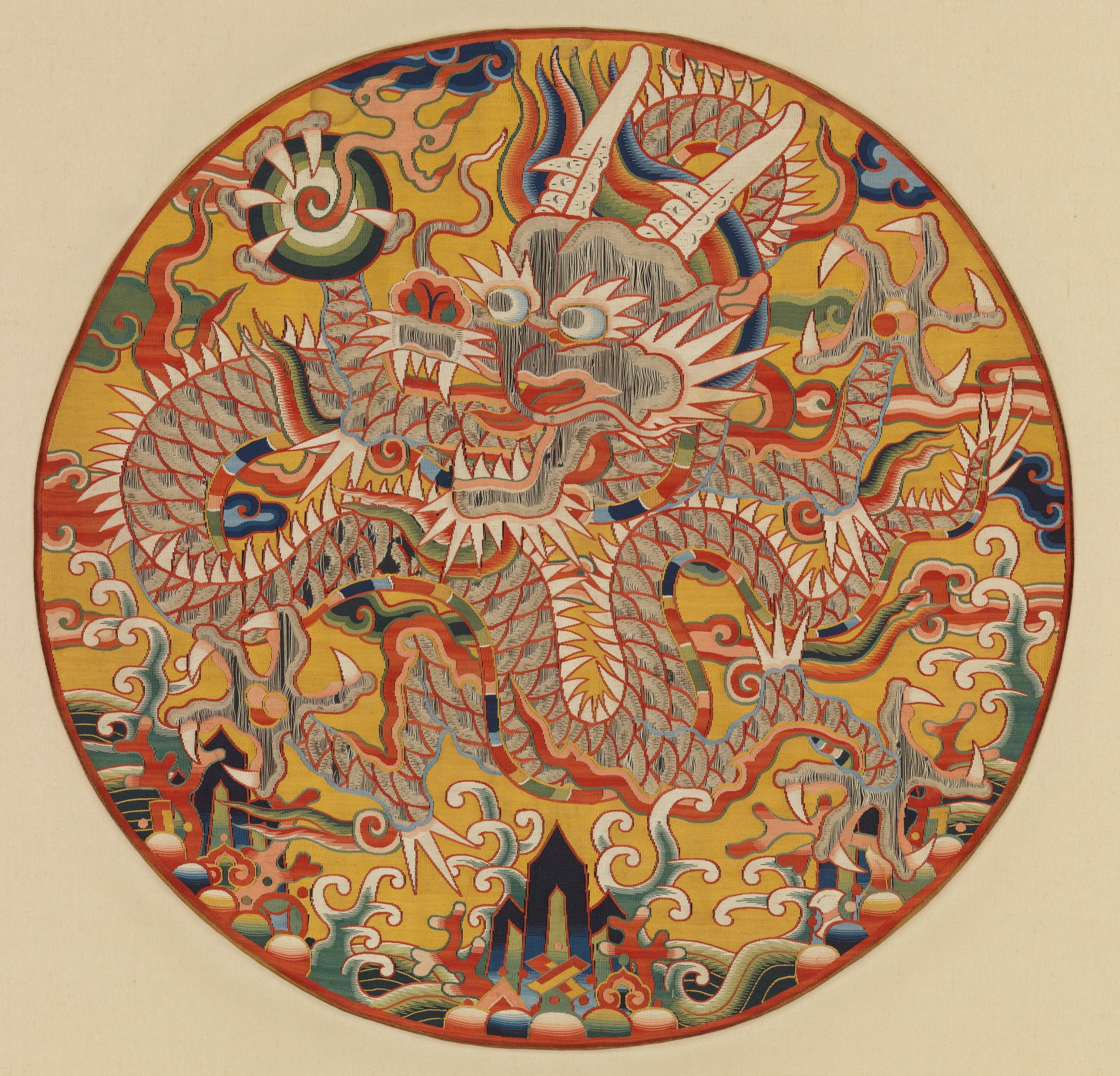

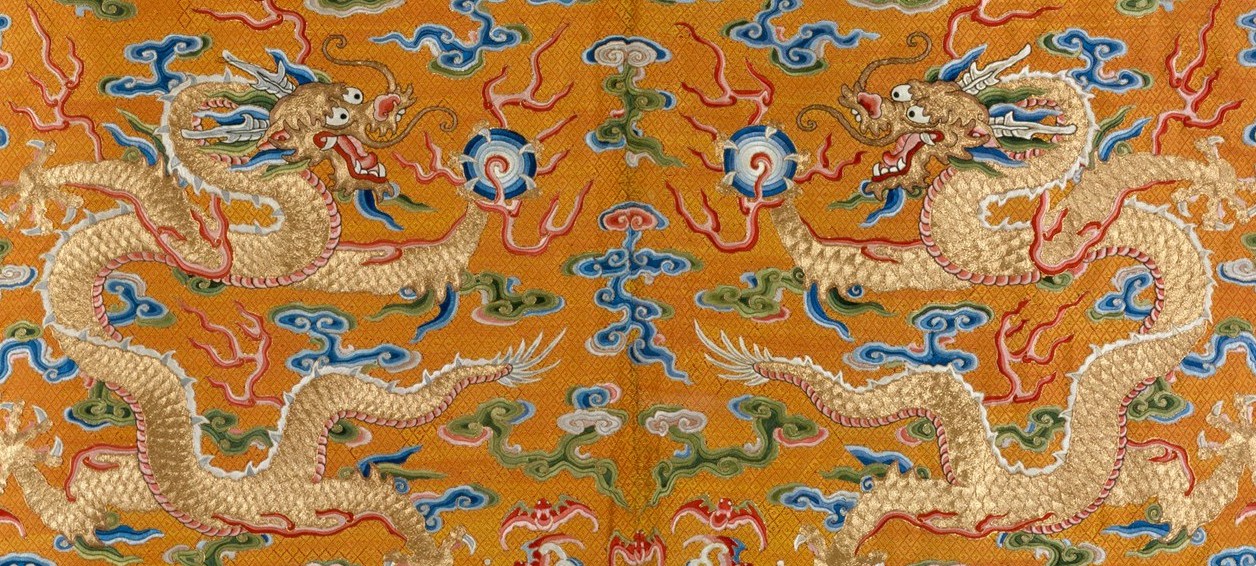

Dragon motifs and designs were featured in many robes of imperial dynasty emperors and empresses.

For more information about Asian Art and teaching resources, please open The Metropolitan Museum of Art link below.

https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/asian-art

https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators

Metropolitan Museum Art Note

“A festival robe, or jifu pao, was worn during festivals, banquets, and other events held in the periods preceding significant sacrificial ceremonies. Only those woven for the emperor, their consorts, and the crown prince were called a “dragon robe” (longpao), and decorated with five-clawed dragons and certain auspicious symbols. The sun, moon, constellation, mountain, dragons, flowery bird, sacrificial cups, waterweed, millet, fire, ax, and the symbol of discrimination “fu,” seen on this robe, were reserved exclusively for imperial robes, as was the bright yellow color. They represent the emperor’s control over all elements of the universe. The powerful, vibrant, and fierce dragons embroidered on this robe date it to the second half of the eighteenth century, implying that it might have been made for the Emperor Qianlong (reigned 1736–95), one of the most famous rulers of the Qing dynasty.” Retrieved November 30, 2022 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/69066

Guanyin was the Chinese goddess of love, compassion, and mercy. In Japan, she is called Kannon and is often associated with dragons. She is sometimes (as in this image) seen riding one. In this image, a carp fish makes its way up to a waterfall and transforms into a dragon. According to the Chinese legend which spread to other parts of Asia, thousands of koi (carp) fish try to leap up the Dragon’s gate waterfall. With grit and determination, only one carp succeeds and as a reward, is transformed into a dragon. The dragon is symbolic of inner strength, perseverance, and courage. In one story, Kannon felt frustrated by her inability to help people resolve their struggles and conflicts. Amida Buddha gave Kannon eleven heads and a thousand arms so that she could see and perceive all the senses, and in the process help people overcome suffering.

Project Gutenberg: Tales of Old Japan (with illustrations by Japanese artists) trans. by Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale, 1837-1916). MacMillan & Co., 1910. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13015/13015-h/13015-h.htm

E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Sandra Brown,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

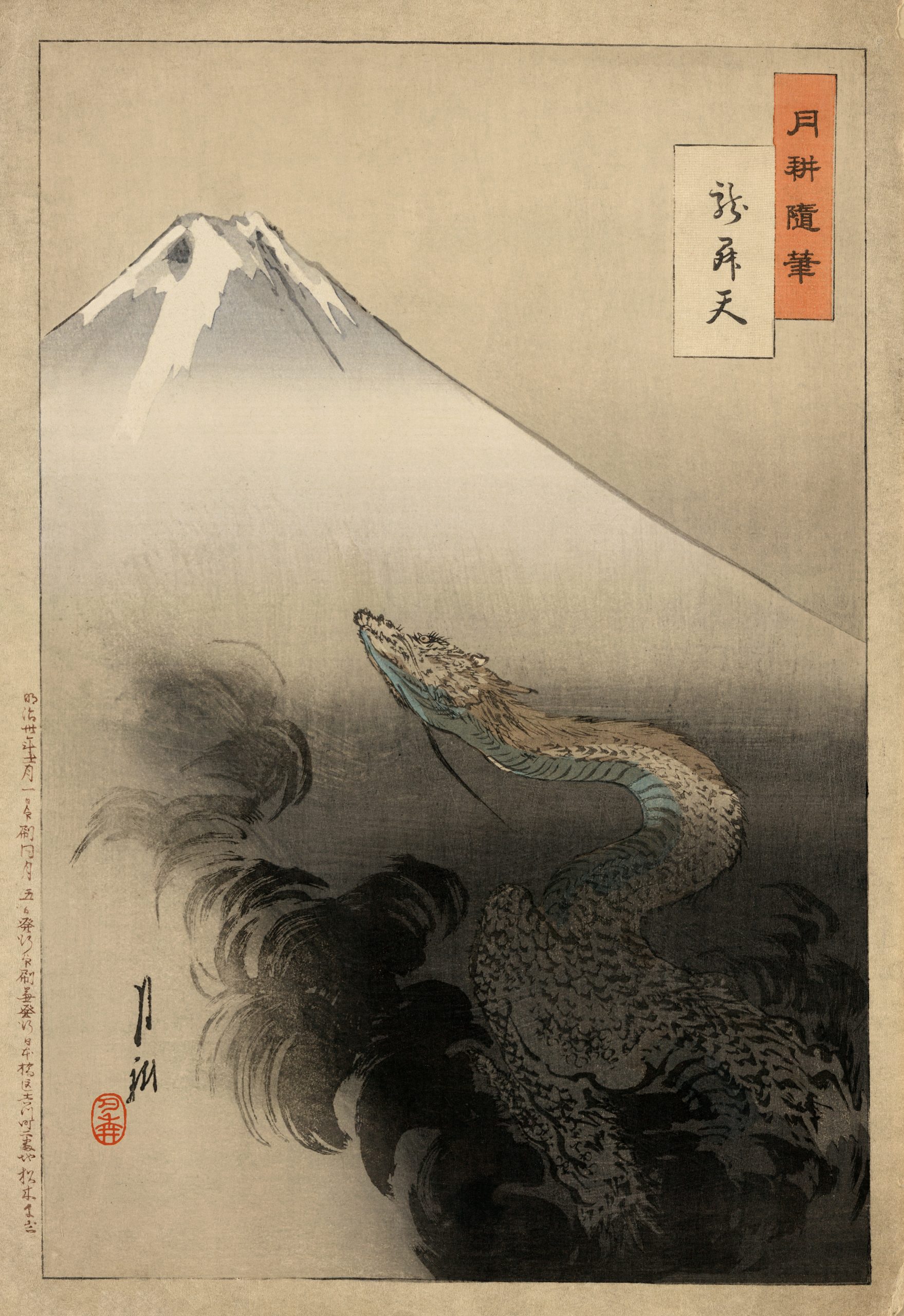

“Dragon Rising up to Heaven”) A dragon ascends towards the heavens with Mount Fuji in the background in this print from Gekko’s Views of Mount Fuji./

Ogata Gekkō (尾形月耕, 1859 – 1 October 1920) was a Japanese artist best known as a painter and a designer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He was self-taught in art, and won numerous national and international prizes and was one of the earliest Japanese artists to win an international audience.

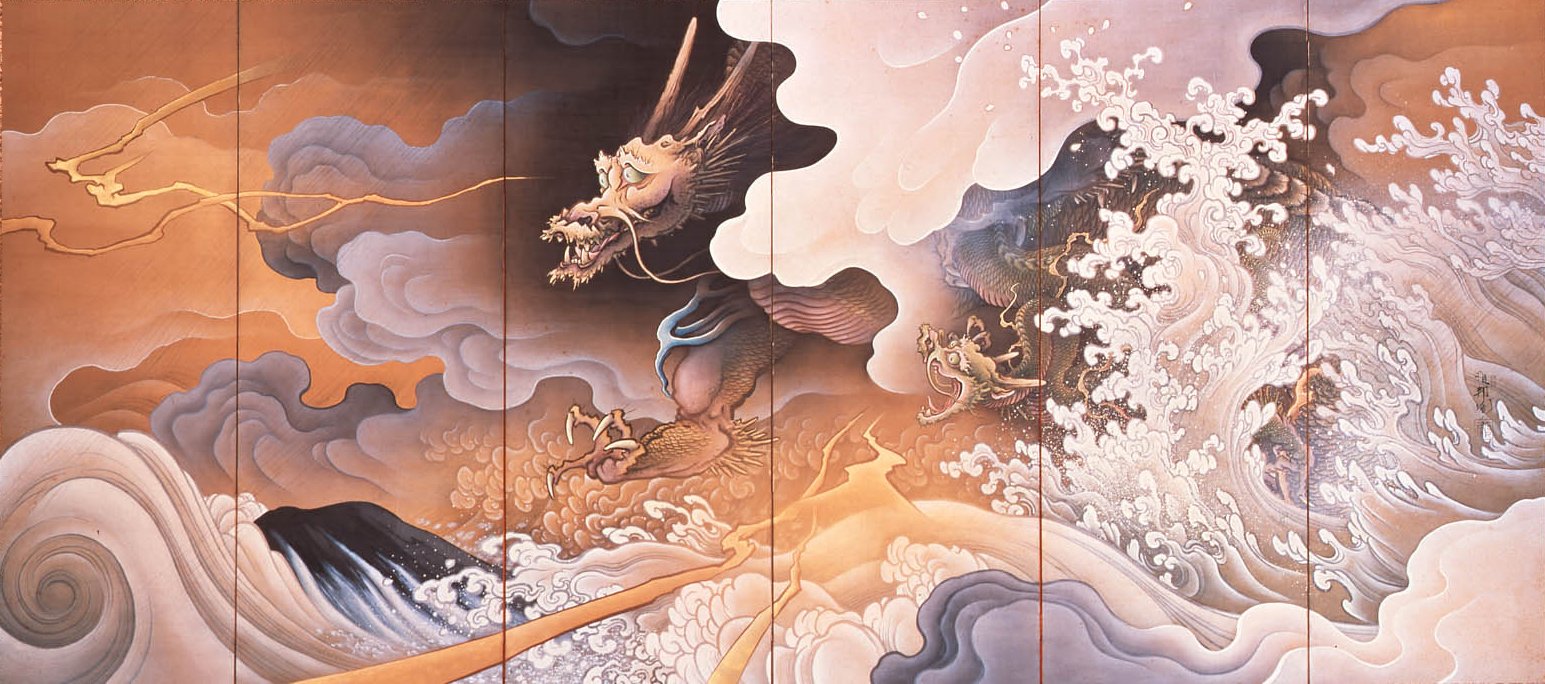

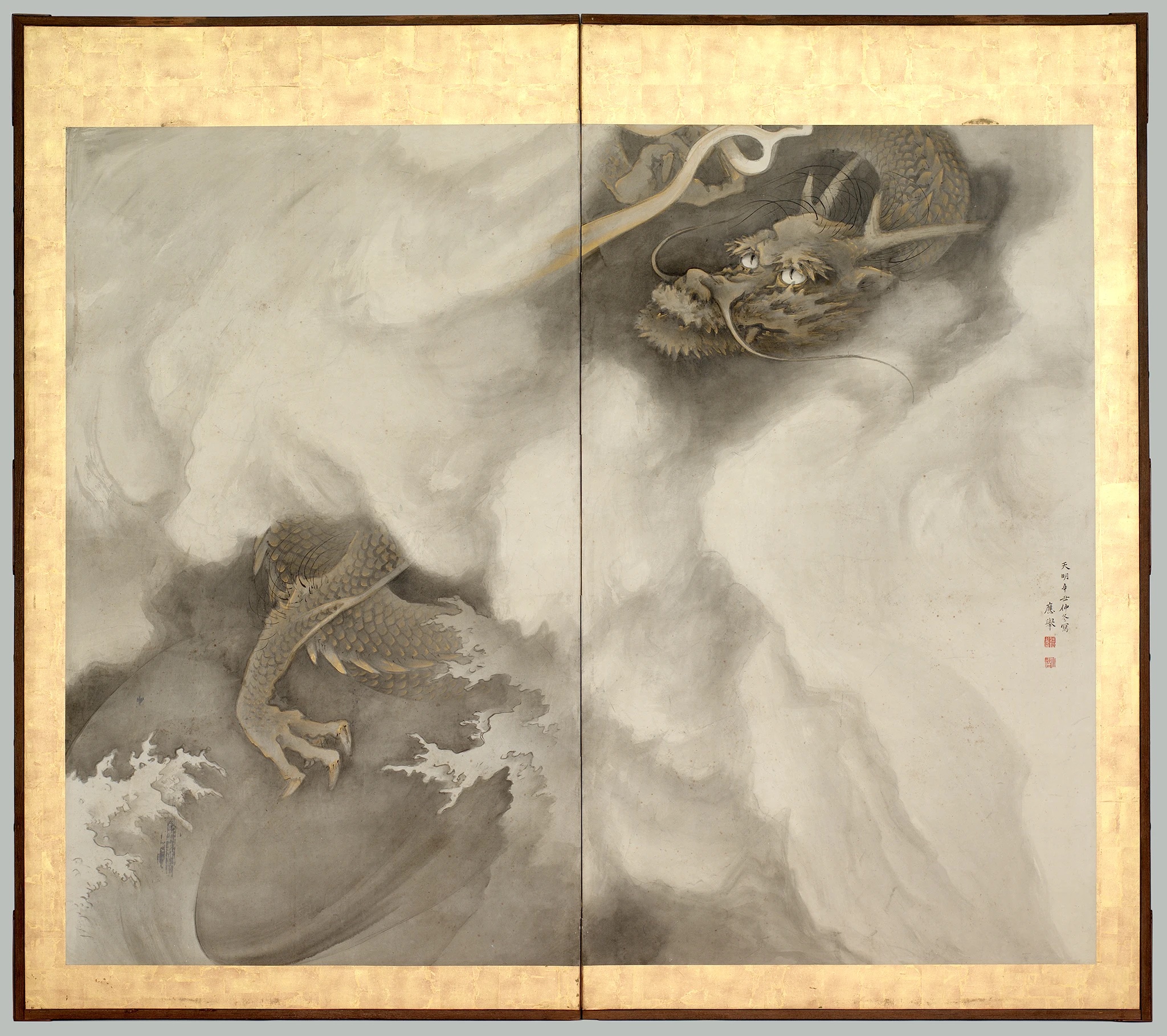

Two-panel folding screen; ink, color paint. Courtesy: Detroit Insitute of Fine Arts, Detroit, Michigan, Founders Purchase.

https://dia.org/collection/tiger-and-dragon%3A-tiger-55972

By Maruyama Ōkyo – https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/tiger-and-dragon-tiger-55972, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79697764

Symbols of Good Fortune: The Tiger and the Dragon

“The tiger is believed to repel evil, while the dragon attracts good fortune. The compound images of the tiger conjuring up the wind and the dragon rising from the crested waves to summon billowing clouds have been the subject of paired paintings by masters of Chinese and Japanese art since the twelfth century. Ōkyo’s screens continue the lineage of imminent artists contributing to this tradition. Ōkyo renders both animals in extraordinary detail, with controlled brushwork giving a rich, soft texture to the tiger’s pelt, while moist scales and vapors lightly washed with gold impart a reptilian feeling to the dragon.” (Retrieved October 12, 2022 https://dia.org/collection/tiger-and-dragon%3A-tiger-55972)

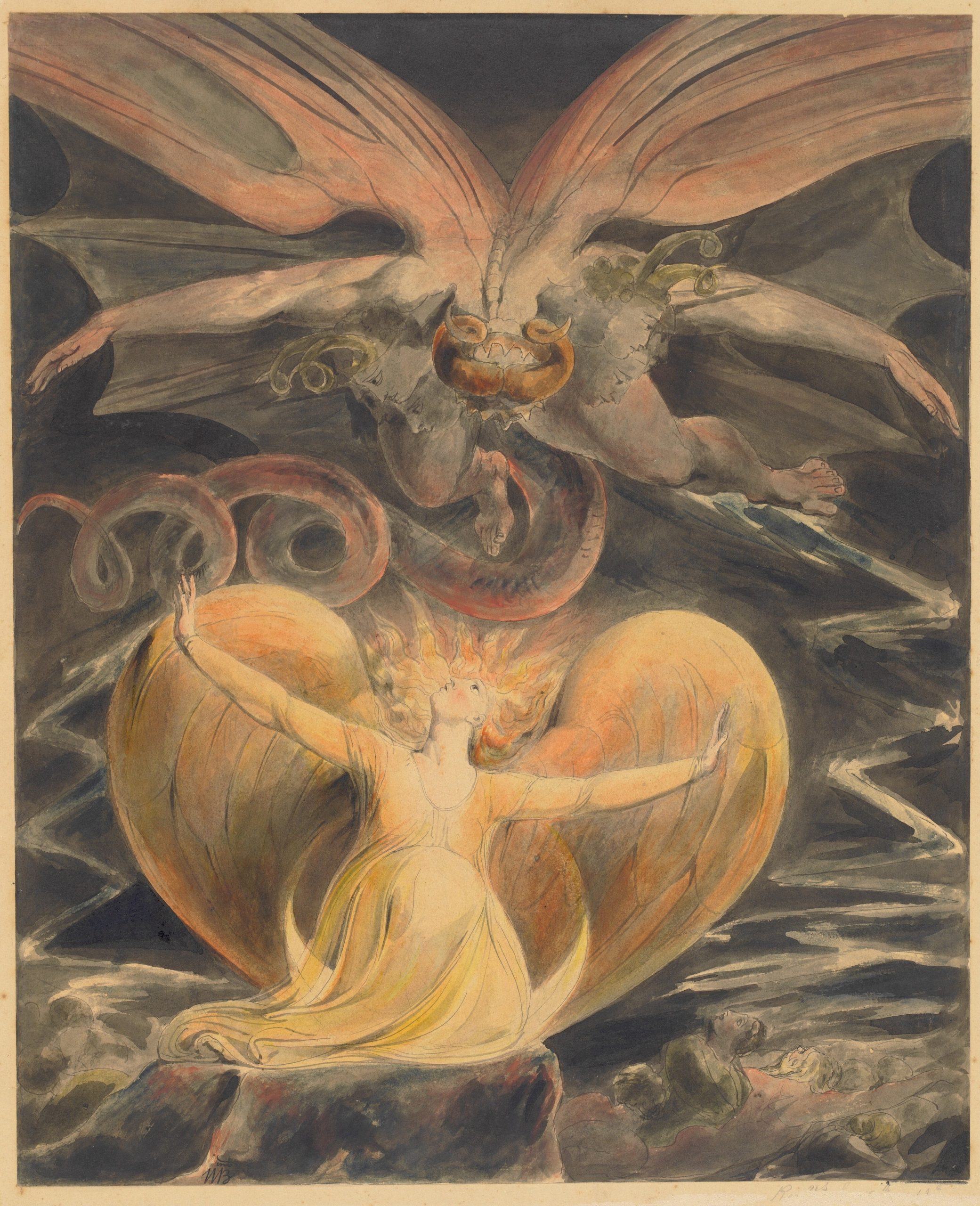

Dragons in Christian Art were Often Connected with Malevolent Forces

For more information about St. George and the Dragon, please open the Wikipedia page below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_George_and_the_Dragon

Inspired by biblical themes and symbols, William Blake’s “The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun” features the cosmic struggle between good and evil. Blake’s artistic interpretations of the final book of the New Testament (The Book of Revelation) are dynamic and visionary. In the specific passage an enormous red dragon is described “With seven heads and ten horns and seven crowns on his heads.” The dragon descends upon a woman “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” (Book of Revelations, The National Gallery of Art Notes. Retrieved September 22, 2022. https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/blake-great-red-dragon-woman-clothed-with-sun.html

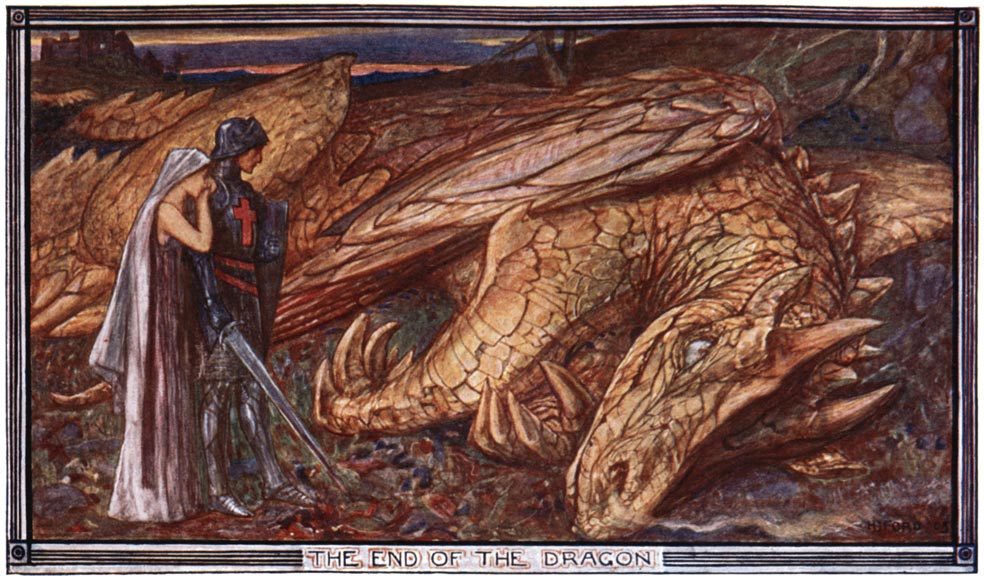

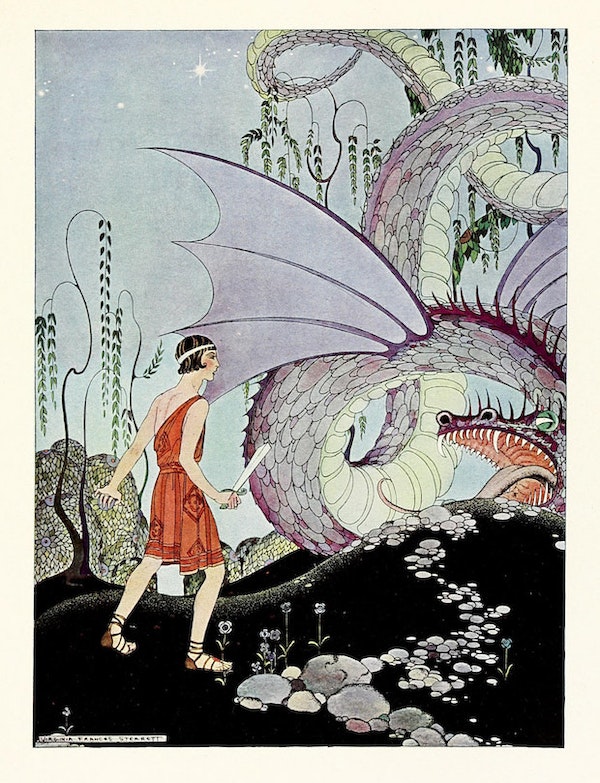

Dragons in Fairy Tale Art

In many European and western folk and fairy tales, dragons are often perceived as a threat to human. The knight is often depicted on a heroic quest to “slay” the dragon and restore peace and calm to a troubled community. The dragon as an archetypal symbol that has simultaneous benevolent and destructive forces can be viewed as a projection on the intrapsychic conflicts of human kind.

Essay: The Dragon as Archetype:

http://www.draconem.net/the-dragon-as-an-archetype/

Dragons in Celtic, Nordic, and Christian Art

“Celtic and Nordic dragons were almost certainly derived from the more ancient myths, though there seems few similarities. We have the Midgard Serpent with its myriad of snakes gnawing at the roots of the World Tree – a corruption of the creation myths of Babylon and Egypt. The story of Sigurd and Fafnir shows the destructive qualities of the Dragon but also illustrates the slaying of the Dragon by the hero. The long-ships used by the Vikings bore on their prows the heads of Dragons, in keeping with the association of Dragons with water. The Celts used Dragons as heraldic symbols such as in the story of Hercules, who after triumphing over Ladon carried the image of the Dragon on his shield. The best example of this is the Welsh Legend of the fight between the Red Dragon of Cadwallader representing Wales and the White Dragon representing the Saxons, also mentioned in the tale of Lludd and Llevelys. Of these representations, only the heraldic device would continue to be used after the Christian ideals spread throughout Europe.

Taking much from the Greek and Arabian legends, the Christians were responsible for turning the Dragon into the image we generally associate with it, that of the fire breathing monster. The Christians used the image of the Serpent, or Dragon, to represent evil, and commonly Satan himself. They drew much from the cultures of the lands they encountered – the legend of St George and the Dragon is taken from the Near East. The Christian image of the Dragon, however, is a perverted one being set up in opposition of the pagan religions such as snake worship. The snake is seen as the Devil in the Garden of Eden, the Dragon is seen as the incarnation of evil in many horrific forms to be vanquished by the hero representing the virtues of God. It is known that the early Christians brought people into their religion by all manner of ways, building churches on old pagan sites for example, and casting the pagan Dragon as the personification of evil and having it defeated by the Christian Hero was a typical ploy.” “-Lawrence Mee, Retrieved November 30, 2022. http://www.draconem.net/the-dragon-as-an-archetype/

“http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24624/24624-h/images/f124-full.jpg” by Project Gutenberg is licensed under CC0 by 1.0.

‘So that is the end of him,’ said the dragon to himself; but, if he had only known, it was the beginning, for the well into which the knight had fallen was the well of life, which could cure all hurts and heal all wounds.

All night Una watched at her post, for darkness had come before the knight received his final blow. In the morning, before the sun had risen above the plain, she [126]was looking for the knight, who was lying she knew not where. Her eyes dropping by chance on the well, she was sore amazed to see him rise out of it fairer and mightier than before. With a rush he fell upon the dragon, who had gone to sleep, safe in the knowledge of his victory, and, taking his sword in both hands, he drove right through the brazen scales, and wounded him deep in his skull. In vain did the monster roar and struggle; the blows rained thick and fast, and most of his tail was cut from his body.

Again and again the knight was overthrown, and again and again he rose to his feet, and laid about him as valiantly as ever. But while the fight was still hanging in the balance, the dragon thrust his head forward with wide-open jaws, thinking to swallow his enemy and make an end of him. Quick as thought the knight sprang aside, and, thrusting his sword in the yawning gulf up to the hilt, gave the dragon his death-blow.

Down he fell, fire and smoke gushing from his nostrils—down he fell, and men thought some mighty mountain must have cast up rocks on the earth.

The victor himself trembled, and it was long ere Una dared draw near, dreading lest the direful fiend should stir. But when at last she knew him dead, she came joyfully forth, and, bursting into happy tears, faltered her gratitude for the good he had wrought her.

There is little more to be told of Una and the Red Cross knight.” (Illustration, p. 126, Andrew Lang (1844-1912), The Red Romance Book, Project Gutenberg, PD/CCO). (Retrieved November 30, 2022

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/24624/pg24624-images.html)

One of the greatest illustrators of myths and children’s books was Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941) His re-imaginations of dragons, sea serpents, and monsters bring a beauty and innocence to each creature.

For the Complete edition of Andrew Lang’s The Red Romance Book (illustrated by Henry Justice Ford), please open the link below.

Sourcehttp://www.gutenberg.org/files/24624/24624-h/images/f124-full.jpg

One of the greatest illustrators of myths and children’s books was Henry Justice Ford. His re-imaginations of dragons, sea serpents, and monsters bring a beauty and innocence to each creature.

For the Complete edition of Andrew Lang’s The Red Romance Book (illustrated by Henry Justice Ford), please open the link below.

Sourcehttp://www.gutenberg.org/files/24624/24624-h/images/f124-full.jpg

For more examples of Katharine Pyle’s illustration and fairy tale writing please open Wonder Tales from Many Lands. Project Gutenberg (Open Access). https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/48351/pg48351-images.html

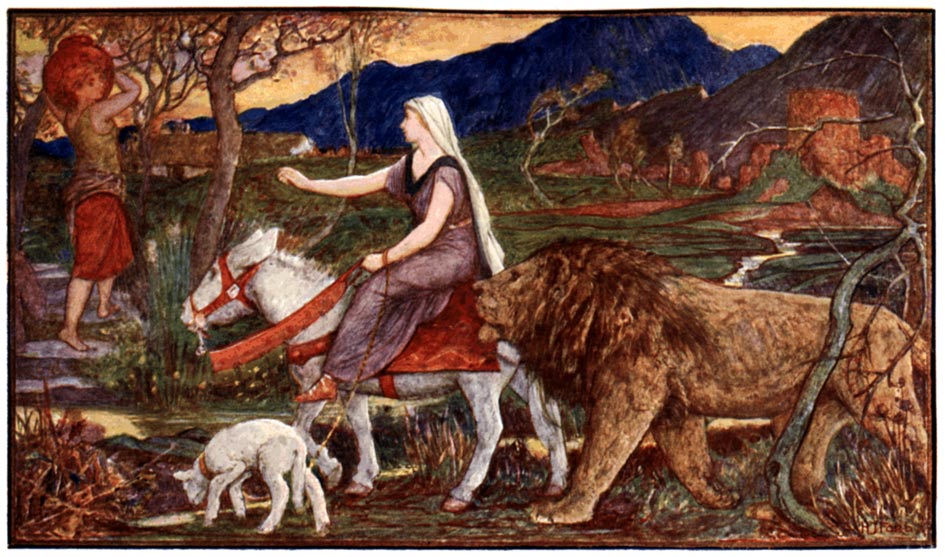

The Red Romance Book Public Domain. Una and the Lion by Henry Justice Ford https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/24624/images/f102-full.jphttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Henry_Justice_Ford

Category:Henry Justice Ford – Wikimedia Commons

“The sun had scarce sent his first beams above the horizon when Una left the hut, mounted on her ass, and, followed by the lion, again began her quest of the Red Cross Knight. But, alas! though she found him not, she met her ancient foe, the magician Archimago, who had taken on himself the form of him whom she sought. Too true and unsuspecting was she, to dream of guile in others, and the welcome she gave him was from her whole heart. In the guise of the knight, Archimago greeted her fondly, and bade her tell him the story of her woes, and how came she to take the lion for her companion. And so they journeyed, the flowers seeming sweeter and the skies brighter to Una, as they went, when suddenly they beheld

One pricking towards them with hasty heat;

Full strongly armed, and on a courser free.” (p. 102. The Red Romance Book by Andrew Lang, Project Gutenberg. Retrieved November 30, 2022 https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/24624/pg24624-images.html)

Forgotten Beauty in Fairy Tale Art

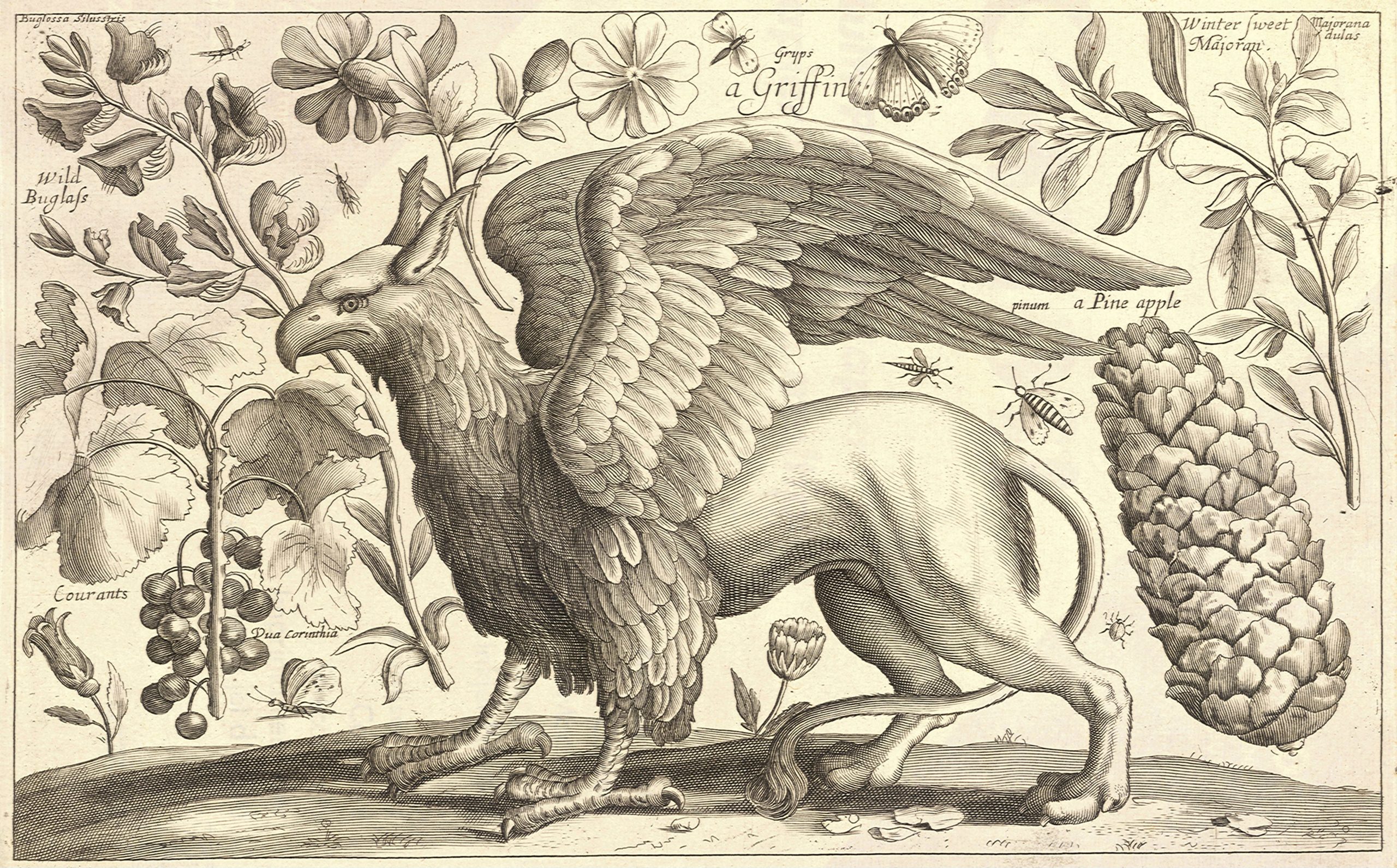

Engravings of Dragons and Winged Creatures

The Griffin (Ancient Greek: Γρύψ Grū́ps) is a legendary creature from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Persian, Minoan, Greek, and Roman mythology that has the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle.

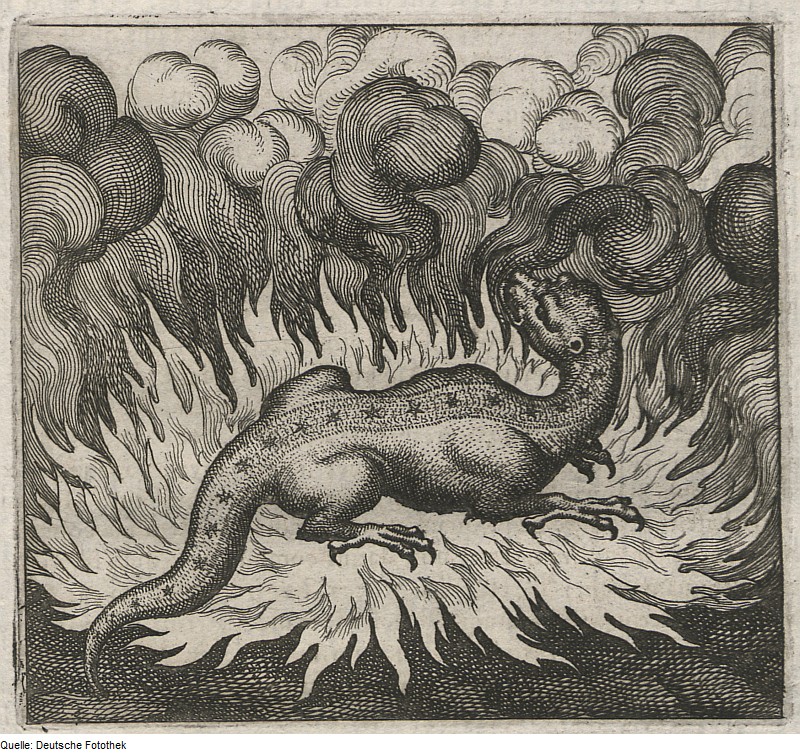

Wyverns

The Wyvern is the symbolic mythological dragon/swan of Leicester, England. Wyvern are mythological creatures that have two legs and the body of a swan, snake, or fish. They are often seen as messages of good fortune.

Lucas Jennis (1590-1630), Engraving of a wyvern-type ouroboros by Lucas Jennis, in the 1625 alchemical tract De Lapide Philosophico. The figure serves as a symbol for mercury

For more information on the engravings and etchings of Lucas Jennis please open the link below.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Lucas_Jennis

“https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/342903” by Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 by 1.0.

Wikimedia and Duetsche Fototek (file donated to the Public Domain)

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/70/Fotothek_df_tg_0008188_Theosophie_%5E_Alchemie.jpg